An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

for Gospel Doctrine Lesson 6:

“Noah … Prepared an Ark to the Saving of His House”

(Moses 8:19-30; Genesis 6-9; 11:1-9) (JBOTL06C)

[See the link to the video supplement for this lesson at the end of this article under “Further Study.”]

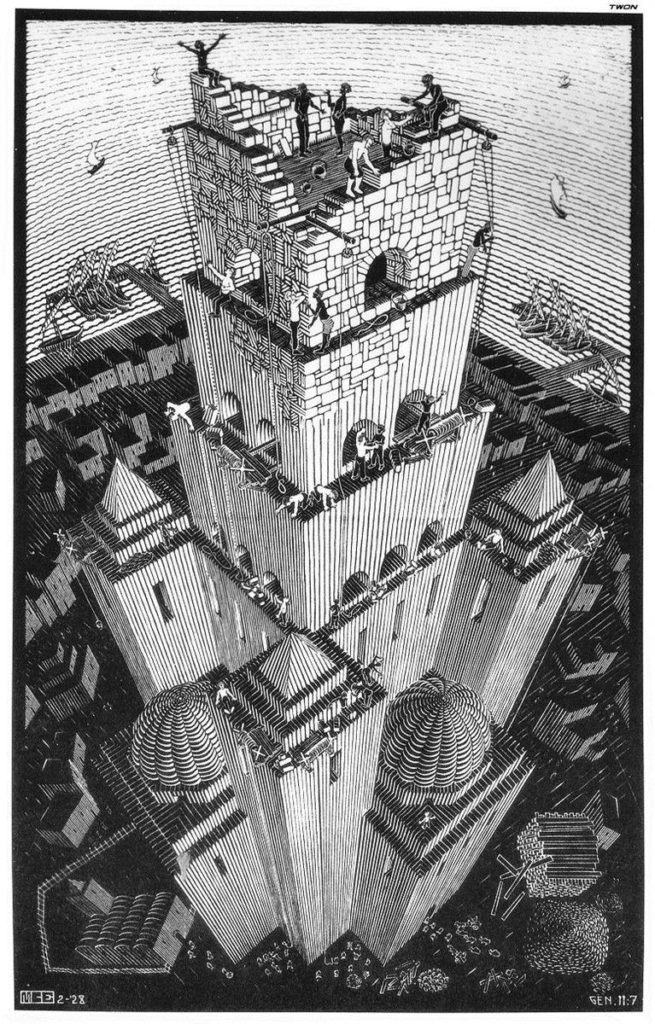

Figure 1. M. C. Esher, 1898-1972: Tower of Babel, 1928. A confused group of different peoples quarrel and cry out as the work comes to a standstill.

Question: At the beginning of the Tower of Babel story, we read that “the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.”[2] Later, we are told that “the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth.”[3] But the scientific history of languages tells us that the diverse tongues of the world did not originate from the splitting of a single language. Must we choose between science and scripture?

Summary: To begin with, the Hebrew word eretz used in Genesis 11:1 (and also in the story of Noah’s flood[4]) can mean either “earth” or “land,” and it is impossible to know which except from context.[5] Here, the phrase probably just means that the people in the land where the story took place originally spoke a common language.[6] In addition, despite the chapter’s focus on the confounding (mixing up) of languages, God’s most important concern seems to have been the confounding (mingling) of the covenant people with their unbelieving neighbors. As with other stories in Genesis 1-11, temple themes are woven throughout the account of the confusion at Babel. In this case, the Tower can be seen as a sort of anti-temple wherein its builders attempted to “make … a name”[7] for themselves rather than acknowledging God as the one who gives names to those He has chosen because of their faithfulness. Abraham’s posterity will be separated out from other nations. His great name “will be achieved not in the present through heroic feats and imposing monuments but rather in a divinely promised future through the begetting of numerous offspring.”[8] Though Abraham successfully passed the tests of his day,[9] his latter-day posterity must continue their vigilance, for the project of Babel is making a strong comeback today.

The Know

Does science support the idea of a splitting of an original language at Babel? The answer is “no.” The story is an interesting puzzle for scholars and scientists. On the one hand, the details of the Babylonian setting and construction techniques for the tower are believable,[10] even if the time frame for the story is difficult to pin down.[11] On the other hand, in light of what is known about the way languages evolve, the biblical story of the confusion of languages at the Tower of Babel seems incredible.

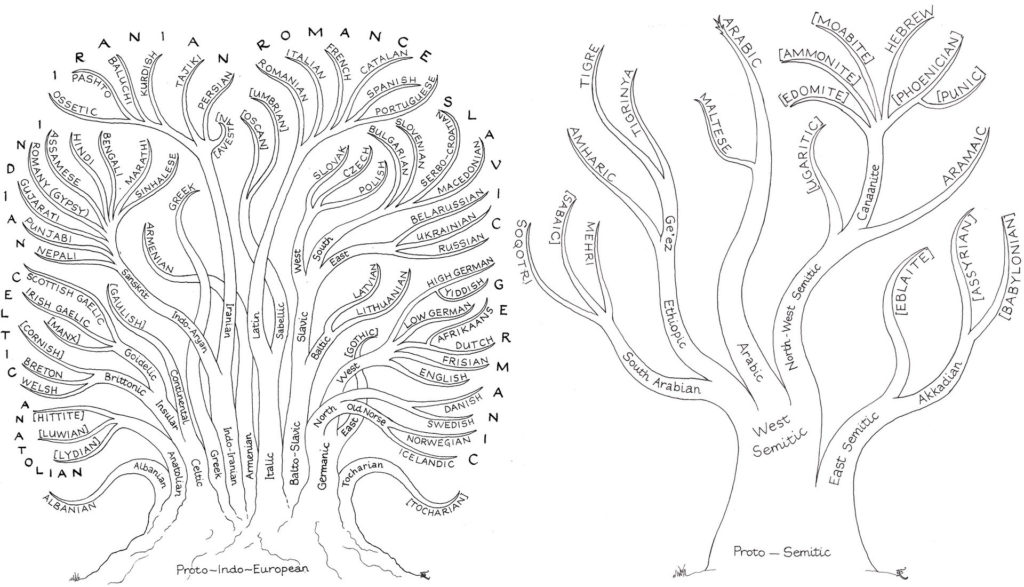

Figures 2 and 3. Katherine Scarfe Beckett, 1972-: Family Trees of the Indo-European and Semitic Languages, 2005

Figures 2 and 3 beautifully illustrate the family trees of the Indo-European and Semitic languages. Guy Deutscher explains how the splitting of language occurs:[13]

Linguistic diversity is … a direct consequence of geographical dispersal and language’s propensity to change. The biblical assertion that there was a single primordial language is not, in itself, unlikely, for it is quite possible that there was originally only one language, spoken somewhere in Eastern Africa, perhaps 100,000 years ago. But even if this were the case, the break-up of this language must have had much more prosaic reasons than God’s wrath at Babel. When different groups started splitting up, going their own ways and settling across the globe, their languages changed in different ways. So the huge diversity of languages in the world today simply reflects how long languages have had to change independently of one another.

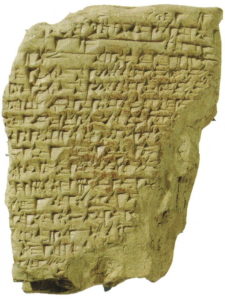

Figure 4. Tablet with Fragment of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

Could there have been some kind of “confounding” of language at Babel after all? The answer is, possibly, “yes.” Perhaps there is a believable way to understand the “confounding” of language at Babel as referring to a local breakdown in the use of a common, regional language rather than a complete breakup of a single, universal language. Some scholars believe that such a language could have played the role of a lingua franca, enabling cooperative work among people who came together from throughout the empire to execute large building projects. In our times, languages such as English, French, and Swahili similarly allow individuals hailing from different places to do business with one another in a common language.

One candidate for such a lingua franca among the Babylonians is Akkadian.[14] A second candidate is Sumerian. In this regard, a segment of a Mesopotamian epic entitled Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta is of special interest. Although translators differ about whether the story describes a past event when one language became many or a future event when all languages would become one, it may resemble the Babel story in its account of the disruption of languages.[15]

If we take the “one language” of Genesis 11:1 as being Sumerian, Akkadian, or even (as a long shot) Aramaic[16] rather than a supposed universal language,[17] some of the puzzling aspects of the biblical account become more intelligible. For example, “Genesis 10 and 11 would make linguistic sense in their current sequence. In addition to the local languages of each nation,[18] there existed ‘one language’[19] which made communication possible throughout the world”[20] — or, perhaps more accurately, throughout the land.[21] “Strictly speaking, the biblical text does not refer to a plurality of languages but to the ‘destruction of language as an instrument of communication.’”[22]

In summary, Victor Hamilton[23] writes that it “is unlikely that Genesis 11:1-9 can contribute much, if anything, to the origin of languages … [T]he diversification of languages is a slow process, not something catastrophic as Genesis 11 might indicate.”[24] The commonly received interpretation of Genesis 11 provides “a most incredible and naïve explanation of language diversification. If, however, the narrative refers to the dissolution of a Babylonian lingua franca, or something like that, the need to see Genesis 11:1-9 as a highly imaginative explanation of language diffusion becomes unnecessary.”[25]

Are “confounding” and “confusing” the same thing? While modern use of the word “confound” typically expresses the element of surprise experienced by someone when an event runs counter to expectations (“the inflation figure confounded economic analysts”[26]), the King James Bible translators would have been aware of its Latin origin as confundere. This word means literally “to pour together, mix, mingle” (com + fundere = together + to pour).[27] Because “confound” has changed its primary meaning in modern English, more recent translations often substitute the closely related term “confuse.” In modern English, “confuse” is a helpful translation, preserving the basic meaning in Hebrew text of mixing up and mingling.

Figure 5. J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: Building the Tower of Babel, ca. 1896-1902

What seemed to be God’s most important concerns about the confusion at Babel? Hugh Nibley argues that the confusion (mixing-up) of language is necessarily connected to the confusion (mingling) of the covenant people with their unbelieving neighbors — a phenomenon that the Lord condemns elsewhere in the Bible and the Book of Mormon.[28]

Though we should remember that textual and interpretive difficulties present in the version of “Genesis” on the brass plates of Laban could have made their way into Moroni’s summary of the story of Babel,[29] the Book of Mormon provides some helpful perspectives on the confusion of languages and people. For example, while warning that “we need to be cautious of … simplistic readings of the scriptural text,” Hugh Nibley provided this careful analysis of the Jaredite story:[30]

The book of Ether, depicting the uprooting and scattering from the tower of a numerous population, shows them going forth [in] family groups [and] groups of friends and associates[31] … There was no point in having Jared’s language unconfounded if there was no one he could talk to, and his brother cried to the Lord that his friends might also retain the language. The same, however, would apply to any other language: If every individual were to speak a tongue all his own and so go off entirely by himself, the races would have been not merely scattered but quite annihilated.

We must not fall into the old vice of reading into the scripture things that are not there. There is nothing said in our text about every man suddenly speaking a new language. We are told in the book of Ether that languages were confounded with and by the “confounding” of the people: “Cry unto the Lord,” says Jared,[32] “that he will not confound us that we may not understand our words.”

The statement is significant for more than one thing. How can it possibly be said that “we may not understand our words”? Words we cannot understand may be nonsense syllables or may be in some foreign language, but in either case they are not our words. The only way we can fail to understand our own words is to have words that are actually ours change their meaning among us. That is exactly what happens when people, and hence languages, are either “confounded,” that is, mixed up, or scattered.[33]

In Ether’s account the confounding of people is not to be separated from the confounding of their languages; they are, and have always been, one and the same process: the Lord, we are told,[34] “did not confound the language of Jared; and Jared and his brother were not confounded … and the Lord had compassion upon their friends and their families also, that they were not confounded.”[35] That “confound” as used in the book of Ether is meant to have its true and proper meaning of “to pour together,” “to mix up together,” is clear from the prophecy in Ether 13:8, that “the remnant of the house of Joseph shall be built upon this land; … and they shall no more be confounded,” the word here meaning mixed up with other people, culturally, linguistically, or otherwise.

Neither the Bible nor the Book of Mormon attributes the scattering of the people to the confusion of tongues. In Genesis, no explicit cause and effect is described — we are told only that “from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth.”[36] Likewise, as Nibley describes:[37]

After the brother of Jared had been assured that he and his people and their language would not be confounded, the question of whether they would be driven out of the land still remained to be answered: That was another issue, and it is obvious that the language they spoke had as little to do with driving them out of the land as it did with determining their destination.

Gardner summarized as follows:[38] “The confounding of languages is related to the mixing (confounding) of different peoples in creating this great tower in Babylon. From such a mixing of people who were attempting to build a [counterfeit] temple to the heavens, Yahweh removed some of His believers [e.g., the Jaredites and, at a future point, Abram] for His own purposes.”

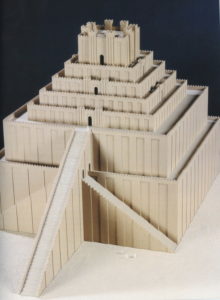

Figure 6. Model of the Marduk Temple Tower at Babylon. Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany, 1999

Is there any evidence for a confusion of peoples in ancient Mesopotamian building projects? The Tower of Babel was almost certainly designed as a Mesopotamian ziggurat. At the top of a ziggurat was a gate where gods would enter the structure from their heavenly abode. At the bottom was a temple, where the gods would further descend to receive the gifts and worship of the people.[39]

Records are scarce for the earliest ziggurats, but inscriptions describe later reconstructions, such as the rebuilding of temple complexes at Babylon (E-temen-anki)[40] and Borsippa (Eur-me-imin-anki) by Nebuchadnezzar II. Inscriptions relating to these later towers attests the use of “bitumen and baked brick throughout” the structures[41] as described in the biblical account.[42] More intriguingly, we read an elaborate description of how workers were gathered from throughout the empire to execute a ziggurat-building project, recalling the biblical imagery of a confusion of languages and peoples:[43]

In order to complete E-temen-anki and Eur-me-imin-anki to the top … I mobilized [all] countries everywhere, [each and] every ruler [who] had been raised to prominence over all the people of the world [as one] loved by Marduk, from the upper sea [to the] lower [sea,] the [distant nations, the teeming people of] the world, kings of remote mountains and far-flung islands in the midst of the] upper and lower [seas,] whose lead-ropes [my] lord Marduk placed in [my] hand so [that they should] draw [his] chariot.

An inscription from Borsippa tells us that the ziggurat had been left unfinished and that, prior to the reconstruction by Nebuchadnezzar II, it had fallen into ruins — a reminder of the uncompleted structures of the biblical Babel:[44]

I built É-temen-anki, the ziggurat of Babylon (and) brought it to completion, and raised high its top with pure tiles (glazed with) lapis lazuli. At that time E-ur-(me)-imin-anki, the ziqqurrat of Borsippa, which a former king had built and raised by a height of forty-two cubits but had not finished (to) the top, had long since become derelict and its water drains were in disorder. Rains and downpours had eroded its brickwork. The baked brick of its mantle had come loose and the brickwork of its sanctum had turned into a heap of ruins.[45] My great lord Marduk stirred my heart to rebuild it.

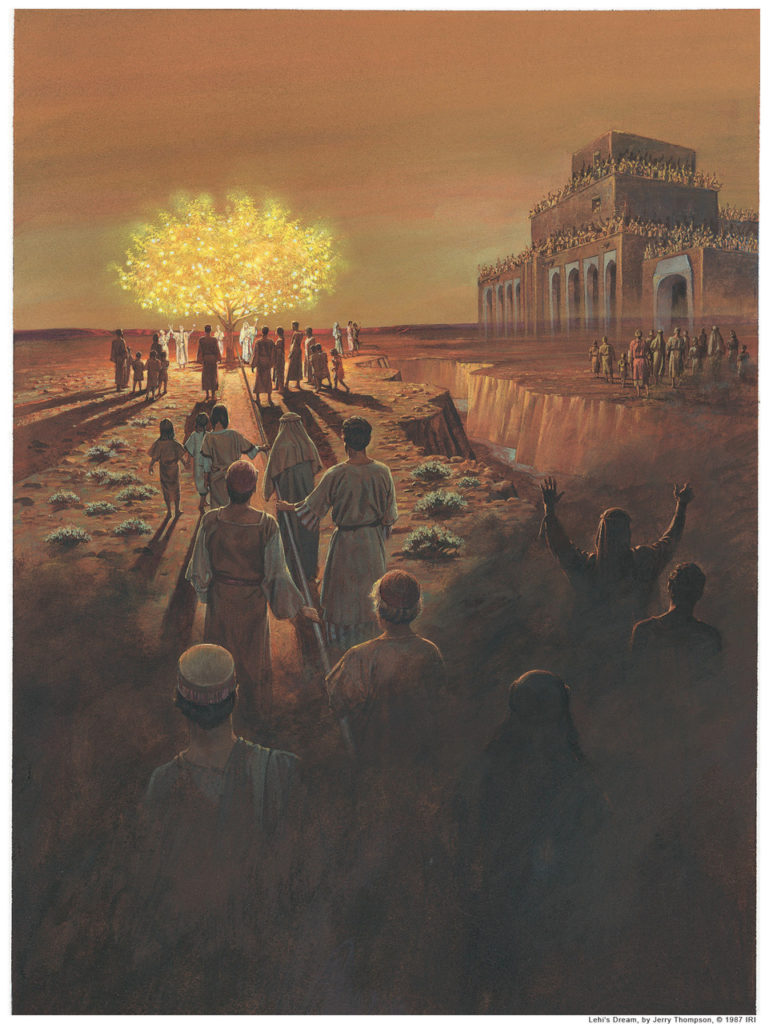

Figure 7. Jerry Thompson: Lehi’s Dream[46]

The Tower of Babel and the “great and spacious building.” When we look closely at the descriptions of the Tower of Babel of Genesis 11 and the “great and spacious building” that “stood as it were in the air, high above the earth” of Lehi and Nephi’s vision[47] we realize that they refer to one and the same building. Indeed, Ellen van Wolde points out that the Hebrew term for “heaven” in Genesis 11:4 “can also mean air, and the word is frequently used in the Hebrew Bible in connection with impressive buildings such as fortresses or towers, as in Deuteronomy 1:28 and 9:1, which speak of ‘great cities and fortresses in the air.’”[48] Nephi described the inhabitants of the building as “the world and the wisdom thereof” and the building itself as “vain imaginations” and “the pride of the world.”[49] Like the Tower of Babel, “it fell, and the fall thereof was exceedingly great.”[50]

The aspirations of the builders that the top of the tower “may reach unto heaven”[51] are contradicted by the statement in Genesis 11:5 that the Lord had to come down to it. Gordon Wenham observes:[52] “With heavy irony we now see the tower through God’s eyes. This tower which man thought reached to heaven, God can hardly see!”

Figure 8. Julee Holcombe, 1972-: Babel Revisited, 2004[53]

The Why

The story of Babel has never been more relevant that it is today. The expanding global monoculture replicates with cold precision the essential conditions for human projects in the style of Babel to sprout and flourish. Paying homage to the 1563 work by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Julee Holcombe’s Tower of Babel is “built of collaged digital images of various buildings from crumbling cheap housing to neo-classical palaces and topped by skyscrapers reaching for the heavens.” According to the artist: “Babel Revisited takes an allegorical gaze at history and modernity and how human beings, like nature, are doomed to the continual repetition of what has gone before.”[54] André LaCocque concludes that the author of Genesis 11 “wants his readers to realize that, among other things, they participate in Babel’s building. ‘Babel’ then becomes the symbol of all of our constructions and fabrications, with their inexorable outcome: confusion (of our life messages) and scattering (of all the pieces of our projects).”[55]

In light of the scattering of the Babylonians, Leon Kass poses these penetrating questions:[56]

Did the failure of Babel produce the cure? Has the new way succeeded? The walk that Abram took led ultimately to the biblical religion, which, by anyone’s account, is a major source and strength of Western civilization. Yet, standing where we stand, at the start of the twenty-first century (more than thirty-seven hundred years later), it is far from clear that the proliferation of opposing nations is a boon to the race. Mankind as a whole is not obviously more reverent, just, and thoughtful. And internally, the West often seems tired; we appear to have lost our striving for what is highest. God has not spoken to us [speaking of Western civilization collectively] in a long time.

The causes of our malaise are numerous and complicated, but one of them is too frequently overlooked: the project of Babel has been making a comeback. … Whether we think of the heavenly city of the philosophes or the post-historical age toward which Marxism points, or, more concretely, the imposing building of the United Nations that stands today in America’s first city; whether we look at the [Internet], or the globalized economy, or the biomedical project to re-create human nature without its imperfections; whether we confront the spread of the post-modern claim that all truth is human creation — we see everywhere evidence of the revived Babylonian vision.

Can our new Babel succeed? And can it escape — has it escaped? — the failings of success of its ancient prototype? What, for example, will it revere? Will its makers and its beneficiaries be hospitable to procreation and child rearing? Can it find genuine principles of justice and other non-artificial standards for human conduct? Will it be self-critical? Can it really overcome our estrangement, alienation, and despair? Anyone who reads the newspapers has grave reasons for doubt. The city is back, and so, too, is Sodom, babbling and dissipating away. Perhaps we ought to see the dream of Babel today, once again, from God’s point of view. Perhaps we should pay attention to the plan He adopted as the alternative to Babel. We are ready to take a walk with Abram.

Further Study

As a video supplement to this lesson, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “A Tower of Literary Beauty: Wordplay and Chiasmus in the Story of Babel” on the Interpreter Foundation website (http://cdn.interpreterfoundation.org/ifvideo/TowerOfLiteraryBeauty.m4v) or on YouTube (https://youtu.be/2enAFPODShs).

For a verse-by-verse commentary on the story of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11, see J. M. Bradshaw, et al., In God’s Image and Likeness 2, pp. 378-438. The book is available for purchase in print at Amazon.com and as a free pdf download at www.TempleThemes.net.

For a video that discusses some of society’s current “Babel projects,” see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “The future isn’t what it used to be: Artificial Intelligence meets natural stupidity.” Presentation at the Second Interpreter Science and Mormonism Symposium, March 12, 2016 (https://latterdaysaintmag.com/the-future-isnt-what-it-used-to-be-artificial-intelligence-meets-natural-stupidity/). Links to an expanded, written version of this presentation published in a series of Meridian Magazine articles can be found here (http://www.templethemes.net/publications.php#mm-future).

For a scripture roundtable video from The Interpreter Foundation on the subject of Gospel Doctrine lesson 6, see https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/scripture-roundtable-56-old-testament-gospel-doctrine-lesson-6-noah-prepared-an-ark-to-the-saving-of-his-house/.

References

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth Edition, 2000). In Bartleby.com. http://www.bartleby.com/61/. (accessed April 26, 2009).

Bradley, Walter. "Why I believe the Bible is scientifically reliable." In Why I Am a Christian: Leading Thinkers Explain Why They Believe, edited by Norman L. Geisler and Paul K. Hoffman, 161-81. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2001.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014.

Brown, S. Kent. "New light from Arabia on Lehi’s Trail." In Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and John W. Welch, 55-125. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Brown, Samuel Morris. In Heaven As It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Deutscher, Guy. The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind’s Greatest Invention. New York City, NY: Henry Holt, 2005.

Gardner, Brant A. Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary of the Book of Mormon. 6 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007.

George, Andrew. "The truth about Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon." In Babylon. (A volume to accompany the exhibition organized by the British Museum, the Musée du Louvre and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), edited by Irving L. Finkel and Michael J. Seymour, 126-30. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2008.

———. "A stele of Nebuchadnezzar II (Tower of Babel stele)." In Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection, edited by Andrew George. Cornell University Studies in Assyriology and Sumerology 17; Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection, Cuneiform Texts 6, 153-69. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2011. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/12831/. (accessed September 2, 2013).

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Harper, Douglas. 2001. In Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/abbr.php. (accessed August 22, 2007).

Inscription on Borsippa by Nebuchadnezzar II, translated by William Loftus. Translated in 1857 for the book ‘Travels and Researches in Chaldea and Sinai’. In Wikipedia. http://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Inscription_on_Borsippa&oldid=3725977. (accessed September 2, 2013).

Kass, Leon R. The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis. New York City, NY: Free Press, Simon and Schuster, 2003.

Kawashima, Robert S. "Sources and redaction." In Reading Genesis: Ten Methods, edited by Ronald S. Hendel, 47-70. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

LaCocque, André. The Captivity of Innocence: Babel and the Yahwist. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2010.

Loftus, William Kennett. Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana; with an Account of Excavations at Warka, the ‘Erech’ of Nimrod, and Shush, ‘Shushan the Palace’ of Esther, in 1849-1852. London, England: James Nisbet, 1857. http://books.google.com/books/about/Travels_and_Researches_in_Chaldaea_and_S.html?id=VJo9AAAAcAAJ. (accessed September 2, 2013).

The Nauvoo Expositor (7 June 1844), typescript. 1844. In Wikisource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Nauvoo_Expositor. (accessed February 2, 2018).

Nibley, Hugh W. 1952. Lehi in the Desert, The World of the Jaredites, There Were Jaredites. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 5. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1957. An Approach to the Book of Mormon. 3rd ed. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 6. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1989-1990. Teachings of the Book of Mormon. 4 vols. Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004.

Oppert, Jules. Textes de Babylone et de Ninive Déchiffrés et Interprétés. Vol. 1: Inscription de Borsippa Relative à la Restauration de la Tour des Langues par Nabuchodonosor, Roi de Babylone. Paris, France: Imprimerie Impériale, 1857. http://books.google.com/books/about/Études_assyriennes.html?id=wyQVAAAAYAAJ. (accessed September 2, 2013).

Ostler, Nicholas. 2005. Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World. New York City, NY: Harper Perennial, 2006.

Pennock, Robert T. Tower of Babel: The Evidence Against the New Creationism. Cambridge, MA: Bradford, The MIT Press, 1999.

Reade, Julian E. "The search for the ziggurat." In Babylon. (A volume to accompany the exhibition organized by the British Museum, the Musée du Louvre and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), edited by Irving L. Finkel and Michael J. Seymour, 124-26. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Sherman, Phillip MIchael. Babel’s Tower Translated: Genesis 11 and Ancient Jewish Interpretation. Biblical Interpretation Series 117, ed. Paul Anderson and Yvonne Sherwood. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Matthew C. Godfrey, Mark Ashhurst-McGee, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley. Documents, Volume 2: July 1831-January 1833. The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman and Matthew J. Grow. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church Historian’s Press, 2013.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

van Wolde, Ellen. Words Become Worlds: Semantic Studies of Genesis 1-11. Biblical Interpretation Series 6, ed. R. Alan Culpepper and Rolf Rendtorff. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1994.

Walton, John H. "The Mesopotamian background of the Tower of Babel account and its implications." Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995): 155-75. http://christiananswers.net/q-abr/abr-a021.html. (accessed August 31, 2013).

———. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006.

———. "Genesis." In Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, edited by John H. Walton. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary 1, 2-159. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

Wenham, Gordon J., ed. Genesis 1-15. Word Biblical Commentary 1: Nelson Reference and Electronic, 1987.

Widtsoe, John A. 1943, 1947, 1951. Evidences and Reconciliations. 3 vols. Single Volume ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1960.

Wiseman, D. J. 1985. Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 1983. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004. http://books.google.com/books?id=1KGMl3B78cgC. (accessed August 13, 2013).

Endnotes

We should remember that when inspired writers deal with historical incidents they relate that which they have seen or that which may have been told them, unless indeed the past is opened to them by revelation. [For example, t]he details in the story of the Flood are undoubtedly drawn from the experiences of the writer. … The writer of Genesis made a faithful report of the facts known to him concerning the Flood. In other localities the depth of the water might have been more or less.

In his essay on chronology in the book of Ether (B. A. Gardner, Second Witness, 6:146-154), LDS scholar Brant Gardner surveys arguments for the dating of the Jaredite migration that range from around 3000 BCE (John Sorenson) to around 1100 BCE (Gardner’s own conclusion). Some scholars date the details of the story of Babel to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (ca. 604-562 BCE), which seems implausible at first glance. It is always possible, however, that a redaction describing an earlier event may anachronistically include details from a later time.

Hugh Nibley distinguished the story in the Book of Mormon from the story in the Bible, arguing that the “great tower” of the Jaredites was linked with Nimrod, and that the “Tower of Babel” was later (H. W. Nibley, Teachings of the Book of Mormon, 1:345. Cf. H. W. Nibley, Lehi 1988, pp. 165-167; H. W. Nibley, Approach, p. 329).

It is a subject in which we are all interested, more particularly the citizens of this county, and surrounding country; the case has assumed a formidable and fearful aspect, it is not the destiny of a few that is involved in case of commotion, but that of thousands, wherein necessarily the innocent and helpless would be confounded with the criminal and guilty….

Thanks to Chris Miasnik for this reference.

Some LDS scholars have looked to the account in the book of Ether as an independent witness of Genesis 11. However, in his lucid commentary on the Book of Mormon, Brant Gardner cautioned that the details of the Jaredite story are not so straightforward as they seem (B. A. Gardner, Second Witness, 6:163). He reminded us that Mosiah only summarized, but did not actually translate the “first part” of the record of the Jaredites that spoke of “the creation of the world, and also of Adam, and an account from that time even to the great tower” (Ether 1:3-4). Thus, it is unlikely that the passing references to that early history we have in the Book of Mormon are based on the Jaredite record. Rather, it is more probable that they have been carried over by Moroni into the book of Ether from what he had learned previously in his study of the brass plates. Specifically, he argues that “the material being translated and Mosiah’s understanding of the [biblical story of the Tower of Babel] had enough resemblances that Mosiah shaped the Jaredites’ original story to match the brass plates’ story at a crucial point” — namely the description of how the language of the builders was confounded. Continuing, he explains (ibid., 6:162):

Based on what we know of how Joseph Smith translated Nephi’s plates, we might expect that Mosiah used a similar method. Thus, when Mosiah saw similar content, he used the familiar language from the brass plates, much as Joseph Smith used the familiar KJV language of Isaiah and Jesus’ 3 Nephi sermon. It would be dangerous to assume that Mosiah used a better or more accurate or literal translation method than Joseph Smith did while translating a document from an unknown language through the same [Nephite Interpreters].

By this means, whatever textual and interpretive difficulties were present in the version of “Genesis” on the brass plates could have made their way into Moroni’s summary of the events surrounding the departure of the Jaredites from the Old World. In the words of Gardner, “By the time Moroni adapted Mosiah’s adaptation, we have the story as given in Genesis because of Genesis, not as an independent confirmation” (ibid., 6:166).

Some might object to this interpretation of events, thinking that since Moroni and Mosiah were prophets they would have surely known what happened of their own accord, not through the medium of the written record. However, Elder John A. Widtsoe explained (J. A. Widtsoe, Evidences, p. 127): “when inspired writers deal with historical incidents, they relate that which they have seen or that which may have been told them, unless indeed the past is opened to them by revelation.”

Babylon was the namesake of the biblical Babel. Sargon of Agade (ca. 2350 BCE) claims to have removed rubble from a clay pit near Agade and heaped it up, naming it Babylon, though the name and the city are thought to have been in use earlier (D. J. Wiseman, Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 1983, pp. 43-44).

The Temple of the Seven Lights of the earth … was built by an ancient king (reckoned to have lived 42 generations before) but he did not complete its head. People had abandoned it at the time of the Flood, without order uttering their words (French: Les hommes l’avaient abandonné depuis les jours du déluge, en désordre proférant leurs paroles). Earthquakes and lightning had shaken its sun- dried bricks; had split the baked bricks of the encasements, and the retaining walls had collapsed in heaps.

One sometimes sees a similar English translation mistakenly attributed to William Loftus (Inscription on Borsippa, Inscription on Borsippa). However the book by Loftus that contains this inscription actually relies on a better translation by Henry Rawlinson that neither contains a reference to the Flood nor to any phrase similar to “without order uttering their words” (W. K. Loftus, Travels, p. 29).