This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

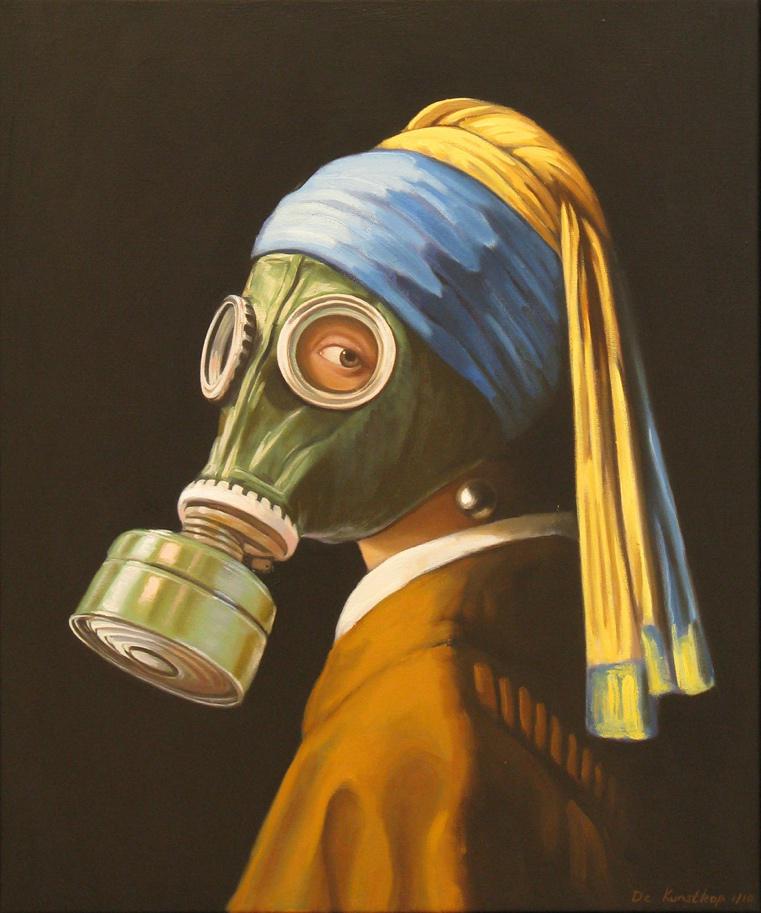

René Jacobs, 1969–: Meisje met gasmasker (Girl with Gas Mask). This painting was inspired by Johannes Vermeer’s (1632–1765) well-known work, Meisje met de parel (Girl with a Pearl Earring), ca. 1669–1670. The gas mask is green rather than black, in ironic harmony with the beauty of nature and the attractive colors of her head scarf.[1]

In a previous Essay,[2] we observed that three distinct parties weep for the wickedness of mankind: God,[3] the heavens,[4] and Enoch himself.[5] In addition, a fourth party, the earth, complains and mourns—though she doesn’t specifically “weep”—for her children.[6] In the present article, we discuss affinities in the ancient Enoch literature and in the laments of Jeremiah to the complaint of the earth in Moses 7:48–49.

Valuable articles by Andrew Skinner[7] and Daniel Peterson,[8] following Hugh Nibley’s lead,[9] discuss interesting parallels to these verses in ancient sources. Peterson follows J. J. M. Roberts in citing examples of Sumerian laments of the mother goddess and showing how a similar motif appears in Jeremiah in the guise of the personified city as the mother of her people[10] by way of analogy to the role of the mourning earth as “the mother of men”[11] in the Book of Moses. Roberts illustrates this by citing Jeremiah 10:19–21:[12]

Woe is me because my hurt!

My wound is grievous.

But I said, “Truly this is my punishment,

and I must bear it.

My tent is plundered and all my cords are broken;

my children have gone out from me, and they are no more;

there is no one to spread my tent again,

and to set up my curtains.

For the shepherds were stupid,

And did not inquire of Yahweh;

Therefore they did not prosper,

And all their flock is scattered.”

Emphasizing the appropriateness of a Sumerian-Akkadian milieu for this concept in Moses 7, Skinner[13] cites S. H. Langdon as follows:[14]

The Sumerian Earth-mother is repeatedly referred to in Sumerian and Babylonian names as the mother of mankind … This mythological doctrine is thoroughly accepted in Babylonian religion. … In early Akkadian, this mythology is already firmly established among the Semites.

Although the motif of a complaining earth is not found anywhere in the Bible, it does turn up in 1 Enoch and in the Qumran Book of Giants.[15] In 1 Enoch we find the following references:

- 1 Enoch 7:4–6; 8:4:[16] And the giants began to kill men and to devour them. And they began to sin against the birds and beasts and creeping things and the fish, and to devour one another’s flesh. And they drank the blood. Then the earth brought accusation against the lawless ones .… (And) as men were perishing, the cry went up to heaven.

- 1 Enoch 9:2, 10:[17] And entering in, they said to one another, “The earth, devoid (of inhabitants), raises[18] the voice of their cries to the gates of heaven … And now behold, the spirits of the souls of the men who have died make suit; and their groan has come up to the gates of heaven; and it does not cease to come forth from before the iniquities that have come upon the earth.

- 1 Enoch 87:1:[19] And again I saw them, and they began to gore one another and devour one another, and the earth began to cry out.

In the Book of the Giants 4Q203, Frag. 8:6–12 we read:[20]

6. ‘Let it be known to you th[at ] [

7. your activity and (that) of [your] wive[s ]

8. those (giants) [and their] son[s and] the [w]ives o[f ]

9. through your fornication on the earth, and it (the earth) has [risen up ag]ainst y[ou

and is crying out]

10. and raising accusation against you [and ag]ainst the activity of your sons[

11. the corruption which you have committed on it (the earth) vacat [

12. has reached Raphael. …

Consistent with other comparisons that have been made between the accounts of Enoch in the Book of Moses, the Qumran Book of Giants, and 1 Enoch, Skinner finds that resemblances to the Qumran Enoch text are more compelling than those found in 1 Enoch. First, he notes that the nature of the wickedness in the Book of Giants is described as “fornication,”[21] which corresponds semantically to the term “filthiness” used in the Book of Moses.[22] By way of contrast, the wickedness being complained of in 1 Enoch is the crimes of murder and violence.

Second, Skinner notes that in both the Qumran Book of Giants fragment and “Moses 7 the earth itself complains of and decries the wickedness of the people, while the [first two] 1 Enoch texts emphasize the cries of men ascending to heaven”[23] by means of the earth.[24]

Skinner also notes that in the Book of Giants and the Book of Moses, “the ultimate motivation behind the earth’s cry for redress against the intense wickedness on her surface” is a plea “for a cleansing of and sanctification from the pervasive wickedness by means of a heavenly personage and heavenly powers. In the Book of Moses the earth importunes,[25] ‘When shall I rest, and be cleansed from the filthiness which has gone forth out of me? When will my Creator sanctify me, that I may rest, and righteousness for a season abide upon my face?’”[26] Likewise, in the Book of Giants, the earth complains about how the wicked have corrupted it through licentiousness and anticipates a destruction that will cleanse it from wickedness.[27]

Conclusions

From a literary standpoint, the complaint of the earth is moving poetry. O. Glade Hunsaker gives two examples:[28]

Enoch hears and describes the personified soul of the earth alliteratively as the “mother of men” agonizing from the bowels of the earth[29] that she is “weary” of “wickedness.” [When the earth began her speech, she commenced with “Wo, wo,” prefiguring the latter echo.] The tension of the drama resolves itself as the voice uses assonance in pleading for “righteousness” to “abide” for a season.

But it is more than poetry, of course. It is also history—and prophecy. Moses 7:61, 64 happily proclaim that “the day shall come that the earth shall rest … for the space of a thousand years” and then woefully inform us that before that relief finally is given, the earth will again suffer great filthiness just before the Lord returns:

The heavens shall be darkened, and a veil of darkness shall cover the earth;[30] and the heavens shall shake, and also the earth; and great tribulations shall be among the children of men, but my people will I preserve.[31]

This article is adapted and expanded from Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 107–108, 154, 157–158, 188–189.

Further Reading

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014, pp. 107–108, 154, 157–158, 188–189. https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/books/in-gods-image-and-likeness-2-enoch-noah-and-the-tower-of-babel/.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005, pp. 140–141, 144–146, 148–150.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986, pp. 11–12, 198–199.

Peterson, Daniel C. “On the motif of the weeping God in Moses 7.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 285–317. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Skinner, Andrew C. “Joseph Smith vindicated again: Enoch, Moses 7:48, and apocryphal sources.” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 365–381. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

References

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/books/in-gods-image-and-likeness-2-enoch-noah-and-the-tower-of-babel/.

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Hunsaker, O. Glade. "Pearl of Great Price, Literature." In Encyclopedia of Mormonism, edited by Daniel H. Ludlow. 4 vols. Vol. 3, 1072. New York City, NY: Macmillan, 1992. http://www.lib.byu.edu/Macmillan/. (accessed November 26, 2007).

Langdon, Stephen H. "Semitic." In The Mythology of All Races. Vol. 5, 12-13. New York City, NY: Cooper Square, 1964.

Maxwell, Neal A. 1975. Of One Heart: The Glory of the City of Enoch. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1980.

Mika’el, Bakhayla. ca. 1400. "The book of the mysteries of the heavens and the earth." In The Book of the Mysteries of the Heavens and the Earth and Other Works of Bakhayla Mika’el (Zosimas), edited by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1-96. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1934. Reprint, Berwick, ME: Ibis Press, 2004.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Parry, Donald W., and Emanuel Tov, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Reader Second ed. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

Peterson, Daniel C. "On the motif of the weeping God in Moses 7." In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 285-317. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Roberts, J. J. M. 1992. "The motif of the weeping God in Jeremiah and its background in the lament tradition of the ancient Near East." In The Bible and the Ancient Near East: Collected Essays, edited by J. J. M. Roberts, 132-42. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

Skinner, Andrew C. "Joseph Smith vindicated again: Enoch, Moses 7:48, and apocryphal sources." In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 365-81. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002.

Wise, Michael, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. New York City, NY: Harper-Collins, 1996.

Thank you for the essay and for the effort to help us… me understand and to help us all…

In my own independent and un professional life…

I speak of my own personal experience with reading and studying all of what I can find regarding ENOCH…

I am uneducated.:. In academic terms of so called higher education… I find it ironic that the “ LAD” is one of the chosen who was slow of speech, slow in speaking- speech… probably also one of little of the world’s educated elite so to speak… ENOCH was obviously intelligent and of great abilities…

Similar pattern as is common with one other prophet of great revere’ … Moses… slow of speech but obviously very intelligent…

As I have and as I continue… those of academia and higher education of secular and spiritual… I appreciate your help in your efforts and work to bring and expose these truths and materials from antiquities and the storage vaults of the educational and religious institutions and the various flavors of religions… and make available to us the uneducated the not lettered, but the curious and truth seekers among us… we may be uneducated and unsophisticated…but some of us ( me not included) have intelligence… to free think and to have an unbiased and unpolluted mind… an educated person has obviously studied and read many authors works…in that the authors can slant subtle shades of light and colors…to bias the so called educated and experts…

So, thank you for the opinions and essays…

Please post as much information from your academic libraries…so that us uneducated can observe the info and understand the information…and with us free to use our own intellectual abilities…and with the LORD OF SPIRIT’s and as the HOLY GHOST…will help us…with out academia and the biased slant of some…