Abstract: The volume editors of The Joseph Smith Papers Revelations and Translations: Volume 4 propose a theory of translation of the Book of Abraham that is at odds with the documents they publish and with other documents and editorial comments published in the other volumes of the Joseph Smith Papers Project. Two key elements of their proposal are the idea of simultaneous dictation of Book of Abraham Manuscripts in the handwritings of Frederick G. Williams and Warren Parrish, and Joseph Smith’s use of the so-called Alphabet and Grammar. An examination of these theories in the light of the documents published in the Joseph Smith Papers shows that neither of these theories is historically tenable. The chronology the volume editors propose for the translation of the Book of Abraham creates more problems than it solves. A different chronology is proposed. Unfortunately, the analysis shows that the theory of translation of the Book of Abraham adopted by the Joseph Smith Papers volume editors is highly flawed.

The translation of the Book of Abraham has been a controversial topic for well over a century. At present a number of theories have been put forward. Publication of the Joseph Smith Papers has provided the means to test the validity of some of the theories proposed for the translation of the Book of Abraham. I will look at two interconnected theories put forward by the volume editors of The Joseph Smith Papers Revelations and Translations: Volume 41 in the light of the Joseph Smith Papers and demonstrate that they are are untenable.

[Page 128]Simultaneous Dictation

The volume editors of JSPRT4 have promoted a testable theory about the translation of the Book of Abraham. The theory is sometimes referred to as the Simultaneous Dictation Theory. This theory is elaborated in detail in the volume itself in a general discussion of the Book of Abraham manuscripts:

The three [Book of Abraham] manuscripts presented here provide insight into the timing of the translation of the Book of Abraham text. The close relationship between the manuscripts created by Williams [labeled Book of Abraham Manuscript–A] and Parrish [labeled Book of Abraham Manuscript–B] indicates that they were begun around the same time — perhaps even concurrently. The leaves on which the two manuscripts were inscribed were originally two halves of a single sheet: one large sheet was separated in two, and the halves were used by Williams and Parrish as the first leaves of their respective documents. The same process was repeated with a second large sheet, the halves of which then served as the second leaves of the two manuscripts. The texts of the Williams and Parrish manuscripts are similar though not identical, as are the revisions, including cancellations and insertions.

Discrepancies in the spelling of several words in the two manuscripts suggest that the manuscripts were not visually compared against one another or against a single earlier version. Given the similarities between the texts of the two manuscripts and the revision process for both, JS may have dictated some or most of the text to both scribes at the same time. In that case, these two manuscripts would likely be the earliest dictated copies of the Book of Abraham. Some scribal errors in the later portion of the manuscript made by Williams, however, indicate that he copied some of his text from another manuscript. JS may have read aloud to Williams and Parrish from an earlier, nonextant text, making corrections as he went; he followed a similar process in his work in the Bible revision project.2

[Page 129]This theory is repeated in the introduction to Book of Abraham Manuscript‑A:

In late 1835, Frederick G. Williams inscribed the following version of the first portion of the Book of Abraham. Williams’s manuscript was closely related to Book of Abraham Manuscript–B, which was inscribed by Warren Parrish. Evidence suggests that large portions of this version and Book of Abraham Manuscript–B were created and revised simultaneously. The similarities in the revisions to the two manuscripts suggest that Williams and Parrish created portions of these texts by taking down dictation and perhaps by copying portions from a nonextant version of the Book of Abraham.3

It is also repeated in the introduction to Book of Abraham Manuscript‑B:

Warren Parrish created this version of the Book of Abraham, which is closely related to Book of Abraham Manuscript–A, the version created by Frederick G. Williams. Evidence suggests that large portions of this version and Book of Abraham Manuscript–A were created and revised simultaneously. The similarities in the revisions to the manuscripts suggest that Williams and Parrish created these texts by taking down dictation and perhaps by copying from a nonextant version of the Book of Abraham.4

Finally, in a joint interview after the publication, the volume editors elaborated on their theory:

JENSEN: Yes. Documentary editors make a big deal of small things sometimes, but it’s sometimes those small things that have lasting implications. There’s one particular instance where there are two documents in here, two Book of Abraham manuscripts in manuscript form. One written by [Warren Parrish] and Frederick G. Williams. These always have posed a challenge. We’ve never known precisely the order in which these were created. And as we looked more closely at these, we realized these documents were created at the same time. In other words, there was some sort of dictation [Page 130]process and then [Parrish] and Williams are capturing this same aural, spoken, text at the same time.

One of the pieces of evidence for that which seems pretty solid is that there was — and we’re really going to get into the nitty-gritty here — but there was one large piece of paper cut in half, divided in half. Those two pieces of paper from the same larger piece of paper make up page one of each of the respective pages of the Book of Abraham. So what we have is pretty compelling evidence that they are there at the same time using the same piece of paper, creating this text, the Book of Abraham, that gives us a new appreciation to the dictation process. Usually when we hear about Joseph Smith dictating, it’s he dictating to one singular scribe. So it’s interesting to imagine trying to reconstruct what that would look like with Joseph Smith dictating to multiple clerks.

HAUGLID: It’s interesting that we’re now talking about this when years and years ago Ed Ashment proposed the same thing. It created a firestorm of rejection amongst our LDS scholars, but now here we are talking about this and agreeing with Ed Ashment.

HODGES: About having multiple clerks in particular at the same time?

HAUGLID: Receiving dictation, yeah.

HODGES: Why was that so controversial?

JENSEN: I have no idea.

HAUGLID: Probably because it was Ed Ashment that proposed it. [laughter]5

Contrary to Hauglid’s assertions that the theory is not accepted because of who first proposed it, there are valid historical reasons for rejecting the theory. As shown shortly, the proposal that multiple clerks recorded [Page 131]newly dictated scripture from Joseph Smith at the same time has serious weaknesses.

Dictation Errors?

The theory of the volume editors (Hauglid and Jensen) contradicts the findings of other editors from the Joseph Smith Papers. The earlier editors concluded that “textual evidence suggests that these Book of Abraham texts were based on an earlier manuscript that is no longer extant.”6 The other editors base these conclusions on the following reasoning: “Documents directly dictated by J[oseph] S[mith] typically had few paragraph breaks, punctuation marks, or contemporaneous alterations to the text. All the extant copies, including the featured text, have paragraphing and punctuation included at the time of transcription, as well as several cancellations and insertions.”7

In their interview, Robin Jensen claims that “there was some sort of dictation process and then Phelps [sic] and Williams are capturing this same aural, spoken, text at the same time.” Since aural errors are associated with dictation rather than visual copying, they can be viewed as a sign that a manuscript is dictated. The volume editors assert that “Discrepancies in the spelling of several words in the two manuscripts suggest that the manuscripts were not visually compared against one another or against a single, earlier version.”8 The footnote gives three differences in spelling: “See, for instance, the misspelling of ‘indeovered’ and ‘endeavoured’, ‘alter’ and ‘altar’, and ‘bedsted’ and ‘bedd stead’.”9

The examples are not dispositive. The volume editors may have misinterpreted the phenomenon they are discussing. In each of the cases listed, Frederick G. Williams has a nonstandard spelling of the word while Warren Parrish has the standard one, and this is typical when one compares the two manuscripts. There is another way to explain this phenomenon. In the production of this manuscript, Parrish could be visually copying but correcting the manuscript he is copying.10

The three examples the volume editors provided are inadequate, since there are dozens of differences between the manuscripts. Most [Page 132]are ambiguous, since they could be explained either as simultaneous dictation or as Parrish editing while copying the text from Williams’s manuscript. A few of the differences, however, cannot be explained if they were both receiving dictation at the same time.

Because the volume editors neither exhaustively cataloged nor even noted the various discrepancies, it has been necessary to compare and collate the manuscripts by cataloging the various discrepancies to determine whether the discrepancies can be accounted for by mishearing a word, visual errors, or editorial correcting.11

Most of the differences between the manuscripts could come from either taking dictation or from Parrish correcting and normalizing the manuscript he was copying. Only 12 of the 147 differences between the manuscripts cannot be explained as Parrish editing Williams, and all of those can also be explained as simple visual copying errors. Twenty-five of the differences (about one in six) cannot be explained as simultaneous dictation errors. A few of the differences, however, can be accounted for only by Parrish’s making a correction to the manuscript in Williams’s hand that he was visually copying.

The hardest differences to explain by reference to simultaneous dictation are the two lengthy insertions. In the manuscript in Williams’s hand, the first of these insertions is crammed between the space at the end of a paragraph and above the already written first line of the next paragraph. In the Parrish manuscript this is continuous flowing text at the bottom of the page.

Williams’s manuscript:

edge of this alter <I will refer you to the representation that is at the(commencement of this record>

It was made after the form of a bedsted such as was had

Parrish’s manuscript:

ledge of this altar, I will refer you to the

representation, that is lying before you

at the commencement of this record.

[end of page]

It was made after the form of a bedd stead

The section corresponding to the first line of the new paragraph in Williams’s hand (“It was made after the form of a bedstead”) is at the top of the next page in Parrish’s manuscript. But if the section were not in [Page 133]the Parrish manuscript, then it would have left an uncharacteristically large margin at the bottom of the page, almost twice the size of any other margin in that manuscript.

| Page of Book of Abraham manuscript in Parrish’s hand | Measurement of Lower Margin (in inches/cm.) |

|---|---|

| 1 | .4/1.04 |

| 2 | .2/.55 |

| 2 (hypothetical) | .9/2.29 |

| 3 | .5/1.38 |

| 4 | .6/1.42 |

| 5 | .6/1.42 |

| 6 | (ends mid-page) |

It is difficult to imagine what sort of simultaneous dictation would have produced the manuscript evidence. For the sake of argument, let’s try (although we will ignore that the dips of the pen in the ink do not support this reconstruction):

Joseph dictates “that you might have a knowledge of this altar.” At this point Warren Parrish stops and pulls out another piece of paper. Joseph then dictates, “It was made after the form of a bedstead such as was had among the Chaldeans.” Joseph then indicates he forgot something. At this point Williams backs up and inserts the text between the lines. Parrish, rather than inserting the text at the top of the new page because he does not have enough room, goes back to the previous page and adds the line in at the bottom of the previous page, but manages to evenly space his lines. Somehow Williams did not hear the words “lying before you” but Parrish did. Joseph apparently made a mistake and Parrish had to strike them out but Williams did not. Then Parrish and Williams pick up where they left off.

If they did pick up where they left off, we would expect a simultaneous re-inking of the pens, but it is difficult to locate where that may have occurred.

The other addition, inserted into the upper margin of the manuscript in Williams’s hand, but included in the text, is harder to explain.

Parrish is normally consistent in his spelling. On the rare occasion where he uses a spelling that for him is unusual, the mistake looks more like a visual copying error that he did not correct. Williams much more frequently [Page 134]uses nonstandard spelling and is not terribly consistent in his orthography.

An example of the variant use of spelling is the word endeavor used in the Book of Abraham. Williams spells it differently every time, but Parrish is consistent in his spelling.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:7 | indeovered | endeavoured |

| Abraham 1:28 | indeaver | endeavour |

| Abraham 1:31 | endeaver | endeavour |

When considering the spelling of altar, Williams and Parrish are consistent in their spellings but Williams consistently uses the nonstandard spelling.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:8 | Alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:10 | alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:11 | alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:11 | alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:12 | alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:12 | alter | altar |

| Abraham 1:20 | alter | altar |

With the spellings of heathen, Williams is inconsistent, including nonstandard spellings while Parrish is consistent.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:5 | hethens | heathens |

| Abraham 1:7 | heathens | heathens |

Parrish is generally more consistent in his use of standard orthography.

Parrish has occasionally one unusual feature to his spelling. In a number of places Parrish drops the final letter or letters of the word. This is a visual copying error.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:8 | strange | strang |

| Abraham 1:9 | made | mad |

| Abraham 1:10 | plains | plain |

| Abraham 1:13 | among | amon |

| Abraham 1:17 | their hearts are turned | their harts are turn |

[Page 135]There are places where Parrish slips in his spelling and follows Williams. For example, Parrish consistently spells the word hearken while Williams consistently spells it harken. But in Abraham 1:7, Parrish spells the word harkened.12 Parrish here follows Williams in spelling the word in a way that is uncharacteristic for him. This is a visual copying error that Parrish did not correct.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:5 | harken | hearken |

| Abraham 1:7 | harkened | harkened |

| Abraham 1:15 | harkened | hearkened |

Consider also the spellings of the god of Elkenah in the two manuscripts. The endings of –er and –ah may have been caused by the /r/ intrusion from Joseph Smith’s accent. The /r/ intrusion adds an /r/ sound at the end of words ending in a long vowel. This can be seen in the switching of the spelling in the Book of Abraham manuscript in Williams’s hand.

| Reference | BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham 1:6 | Elk=kener | Elkkener |

| Abraham 1:7 | Elk=Kener | Elkken[er] |

| Abraham 1:7 | Elk=Keenah | Elkkener |

| Abraham 1:13 | Elk-keenah | Elkkener |

| Abraham 1:17 | Elk kee-nah | Elkkener |

| Abraham 1:20 | Elkeenah | Elkken{ah|er} |

| Abraham 1:29 | Elkeenah | Elkkener |

While Williams used a number of different spellings for the deity, Parrish consistently used the same spelling, the first one that Williams used, except one time when he wrote the same ending as Williams and then corrected it to his version of the spelling. If this were a dictation error, one would have expected Parrish to consistently hear the –er ending and write it. Parrish’s consistency makes this example easier to explain as a visual copying error rather than an aural copying error.

The volume editors have not only mischaracterized ambiguous differences between the manuscript to match a preconceived theory, but they have also missed the differences in the manuscripts which indicate other theories that have greater explanatory power. The theory that [Page 136]Parrish copied and normalized Williams’s manuscript explains more of the features than the simultaneous dictation theory does.13

Some might point to identical corrections between the Book of Abraham manuscripts in Parrish’s and Williams’s hands as evidence for simultaneous dictation. The evidence for this does not necessarily support the argument. Here is the evidence for the scribal corrections in Williams’s hand from the Book of Abraham manuscripts before the long insertions. (I have used my transcriptions, since there are a couple of errors in the JSPRT4 transcriptions here.)

| BoA-M-Williams | BoA-M-Parrish | BoA-M-Phelps/Parrish |

|---|---|---|

| first seccond (line 1) | first second (page 1, line 1) | |

| my mine (line 2) | the mine (page 1, line 2) | mine (page 1, line 22) |

| whereunto unto (line 2) | whereunto unto (page 1, lines 2–3) | unto (page 1, line 22) |

| d{m|u}mb (line 12) | dumb (page 1, line 22) | dum (page 2, line 5) |

| E{k|l}k=Keenah (line 15) | Elkkener (page 1, line 26) | Elkkener (page 2, line 9) |

| the{m|se} (line 18) | these (page 2, line 1) | these (page 2, line 14) |

| {S}un (line 22) | son sun (page 2, line 9) | Sun (page 2, line 22) |

| Pot{t|i}pher<s> (line 24) | Potiphers (page 2, line 12) | Potiphers (page 2, line 25) |

| plains (line 25) | plain (page 2, line 13) | plain (page 2, line 26) |

| {offer|up}on (line 26) | upon (page 2, line 14) | upon (page 2, line 27) |

| regular royal (line 28) | regular royal (page 2, line 17) | royal (page 2, line 30) |

| {p|di}scent (line 28) | descent (page 2, line 17) | descent (page 2, line 30) |

| wor{e|s}hip (line 30) | worship (page 2, lines 19–20) | worsh=ip (page 2, lines 33–34) |

| were Killed (line 31) | were Killed (page 2, line 21) | were Killed (page 3, line 1) |

Of the fourteen scribal corrections that Williams makes, three are copied by Parrish, two in the first two lines, and one later on. This is hardly an indication of Joseph making a correction in dictation that both men are following. In the second error Williams makes, Parrish makes a different error but makes the same correction. But one can see that where Parrish is copying his own work, he copies his own mistake (e.g., “Potiphers”). One can also see that where Williams capitalized Killed in the middle of the sentence, Parrish copies the error not once but twice. So Parrish could and did copy both errors and corrections. But the fact that he did not match all the errors argues against simultaneous [Page 137]dictation. For example, Williams has a corrected my appointment while Parrish has a corrected the appointment in Abraham 1:4. Williams had to correct them strange gods in Abraham 1:8 (this could be seen as a correction of them to these strange gods), but Parrish did not. The fact that the errors and corrections are not consistent argues against the two manuscripts being dictated simultaneously.

It may also be worth noting that one of the early errors Williams corrects (offered {offer|up}on in Abraham 1:11) is a dittography, the first of multiple in this manuscript, which in Joseph Smith’s scribes in 1835–1836 is more typical of a copying error than a dictation error.

Scribal Employment

Comparison of the manuscripts does not support the simultaneous dictation scenario proposed by the volume editors. It substantially undermines it, showing that Parrish copied and edited Williams’s manuscript. But to prove that the scenario of simultaneous dictation by Joseph to Williams and Parrish is impossible, one has only to ask one question: When did this supposed simultaneous dictation take place?

The volume editors have very helpfully specified that they think the translation took place between July and November 1835 and have included this in the title of both of the Book of Abraham manuscripts in question. So were Warren Parrish and Frederick G. Williams ever scribes together during this time?

The dates that Frederick G. Williams served as scribe are somewhat restrictive: We know of only 28 September 1835,14 3–7 October 1835,15 16 November 1835,16 and 23–26 December 1835.17 On 2 November 1835, Williams even proposed leaving town.18

Warren Parrish, whom Joseph Smith even designated “my scribe,”19 was more commonly employed as a scribe during this time, but not all of it. In July of 1835, Warren Parrish was serving a mission and was the companion of Wilford Woodruff. Parrish had finished his time [Page 138]on a mission and took his departure from Woodruff on 23 July 1835 in Sandy, Kentucky, about 265 miles from Kirtland.20 The earliest mention of him in Kirtland was on 17 August 1835 when he took minutes of the general assembly of the Church.21 Joseph Smith was out of town22 and noted as “absent.”23 He also served as a clerk for a meeting of the Kirtland High Council on 28 September 1835.24 After two experiences drafting documents for Joseph Smith on 23 and 27 October 1835,25 Parrish was hired as Joseph Smith’s scribe on 29 October 1835.26 On that day, they “went to Dr. Williams after my large journal.”27 Parrish served daily in the scribal capacity from that time until 18 December 1835,28 when he took ill. He began again about a week and a half later on 27 December 1835 and served daily until 22 January 1836.29 Williams served as a scribe only during times when Parrish was unavailable.

Parrish and Williams were also together with Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Oliver Cowdery on 2 November 1835 when they, along with “a number of others went to Willoughby to Hear Doct Piexotto deliver a lecture on the profession theory & practice of Physic,” after which they “returned home.”30 It does not appear that there was any time taken to work on translation on this occasion.

The only day when both Williams and Parrish served as scribes together was on 16 November 1835. On that day, Joseph Smith “dictated a letter for the Advocate, also one to Harvey Whitlock.”31 The letter to the Messenger and Advocate was over 2,500 words long and filled three [Page 139]printed pages,32 and probably took ten manuscript pages.33 The letter to Harvey Whitlock was three manuscript pages, and both it and the original letter from Harvey Whitlock were copied into Joseph Smith’s journal. About one page of the copying was taken over by Williams. At around 20 pages, Parrish is known to have written more on that day than on any other day when he was employed as Joseph Smith’s scribe. Only on two other days is Parrish known to have written anything close to what he did on that day.34 The effort seems to have taken Parrish all day.35 In the evening, Joseph Smith was busy with a council meeting.36 Williams takes over copying a page after Parrish has already written about 13 pages, and Williams seems to have been at Joseph Smith’s to take part in that evening’s council. This particular day seems a very unlikely time for the simultaneous dictation to take place.

The day of 19 November 1835 is another possible time when Williams and Parrish were together in the presence of Joseph Smith. The journal entry reads:

Thursday 19th went in company with Doct. Williams & my scribe to see how the workmen prospered in finishing the house; the masons on the inside had commenced putting on the finishing coat of plastureing, on my return I met Loyd & Lorenzo Lewis and conversed with them upon the subject of their being disaffected. I found that they were not so, as touching the faith of the church but with some of the members.

I returned home and spent the day in translating the Egyptian records:37

What is not clear from the journal entry is whether Williams accompanied Smith and Parrish only to the temple, or whether he was with them the entire day. This is the only possible day mentioned in the journals when Williams and Parrish could have worked together as scribes on the Book of Abraham, and it is not clear they did so. While [Page 140]such an event might have occurred without being recorded in the journal, one still has to argue for something on the basis of no evidence, which appears exactly the same as making it up.

In December 1835, the handwriting in Joseph Smith’s journal changes. For four days (19–22 December 1835), Joseph Smith writes his own journal.38 Then Williams takes over for the next four days (23–26 December 1835).39 A similar pattern occurs in late January and early February 1836 when Parrish’s “ill health” prevented him from writing for Joseph Smith when he complained that “writing has a particular tendency to injure my lungs.”40 The last of those days in December, Williams and Parrish are together again with Joseph Smith, but Joseph Smith says that he “commenced studeing the Hebrew Language in company with bros Parish & Williams in the mean time bro Lyman Sherman came in and requested to have the word of the lord through me.”41 On that day the three were studying Hebrew, not Egyptian, and were interrupted. Parrish takes up the scribal duties again the next day.42 But this is after the period when the volume editors speculate that the Book of Abraham manuscripts were produced.

So during the period when the volume editors claim the Book of Abraham manuscripts were produced, Frederick G. Williams served as scribe only when Joseph Smith’s regular scribe, Warren Parrish, was not available because (1) he had not been hired yet, or (2) he was ill. The only occasions during that time when it is known that Smith, Williams, and Parrish are together, they are doing something else.

There is something else odd about these particular dates. The only days when Parrish and Williams worked together were 16 November 1835, 19 November 1835, and 26 December 1835. Consider these dates in the context of known work on the Book of Abraham:

| Date | Present | Work on the Book of Abraham |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 1835 | JS, OC, WWP | “labored on the Egyptian alphabet” “The system of astronomy was revealed”43 |

| 7 October 1835 | JS, FGW | “recommenced translating the ancient records”44 |

| [Page 141]16 November 1835 | JS, WP, FGW | “dictated a letter”45 |

| 19 November 1835 | JS, WP, (FGW?) | “spent the day in translating the Egyptian records”46 |

| 20 November 1835 | JS, WP | “we spent the day in translating”47 |

| 24 November 1835 | JS, WP | “we translated some of the Egyptian, records”48 |

| 25 November 1835 | JS, WP | “spent the day in Translating.”49 |

| 26 November 1835 | JS, WP | “we spent the day in transcribing Egyptian characters from the papyrus”50 |

| 28 November 1835 | JS, WP | “I think I shall be able in a few days to translate again”51 |

We cannot prove that Williams is involved in the 19 November translation session. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Williams did not just visit the Kirtland temple with Smith and Parrish but continued with them the rest of the day; and that contrary to all our manuscript evidence, the Book of Abraham manuscripts in the handwriting of Parrish and Williams were simultaneously dictated. Since this would be the last known time in the proposed time of translation of the Book of Abraham that Frederick G. Williams participated in the translation, all of the text in his hand would have had to be done on that day. The manuscripts are certainly within the known and expected range of what Williams and Parrish could do as scribes. The manuscript in Parrish’s hand does not cover as much of the text as Williams does. Why does Parrish stop early? Over the next week and a half Parrish is also involved in the same translation on four separate occasions. Where is the text? If Abraham 1:4–2:6 (32 verses) are covered in one day, should we not expect about 128 more verses over the next four translation sessions? Since there are only 101 more verses in the published Book of Abraham, what does such a scenario say about the pace of translation of the Book of Abraham?

Looked at another way, Parrish’s handwriting is only on the following materials:

[Page 142]Book of Abraham Manuscript-C = CHL Ms. 1294, fd. 1, 10 pages

Book of Abraham Manuscript-B = CHL Ms. 1294, fd. 3, 6 pages

Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language = CHL Ms. 1295, fd. 1, four scattered entries, none exceeding a single paragraph.

We know that Parrish is involved in five translation sessions, yet all of that amounts to at best eighteen pages of material, six of which can be produced in a single session. At best that can account for three of the sessions. Where is the rest of the Book of Abraham material in Parrish’s hand? Since the rest of the material is simply copying, why was it called translating?

The proposed theory of simultaneous translation does not account for the manuscript evidence, or the historical evidence.

Errors in Joins

Finally, the volume editors raise the issue of joins, but their statements need to be examined. Although the volume editors raise the issue, their simultaneous dictation theory does not depend on it. The simultaneous dictation theory could still be true even if their observations about manuscript joins were false.

Manuscript joins are very important in work with fragmentary documents.52 In this case, the join tells us less about the document and more about the source of the paper for the documents. A number of ledger volumes had been purchased,53 some of which were mined for paper by taking quires and cutting the larger folded sheets apart at the fold in the gutter. Indeed, although unnoted by the volume editors, the ledger volume containing the Grammar and Alphabet document has indications that at least one quire has been removed from the volume. Since the cuts were freehand, there are irregularities that allow for different parts of an original leaf to be matched together to [Page 143]show they were once together. There is no real meaning to this phenomenon, since the main purpose was simply getting usable sheets of paper. The volume editors, however, try to use this to hypothesize that two manuscripts that both have one page from an originally larger sheet of paper were created at the same time. I have long been interested in the phenomenon of joins since I first noticed it and pointed it out to Hauglid. At the time, I could not find any other joins between manuscript sheets when looking at the originals, so their announcement that the second leaves also joined came as a surprise, since I had checked that in the originals and had not found that to be the case.

The volume editors use the term leaf to refer to a sheet of paper. They use the term page to refer to the side of a leaf. Each leaf has two pages: the front side (called the recto) and the back side (called the verso).

The volume editors are correct in the first half of their statement. The first leaf of what they call Book of Abraham Manuscript–A originally joined to the first leaf of what they call Book of Abraham Manuscript–B before being separated. The rectos were on the same side of the original sheet. The separate leaves, however, were originally oriented upside- down to each other so the left sides of the rectos of the two leaves join. The divergent orientation as well as the formatting for each leaf indicates that the leaves were separated before they were inscribed.

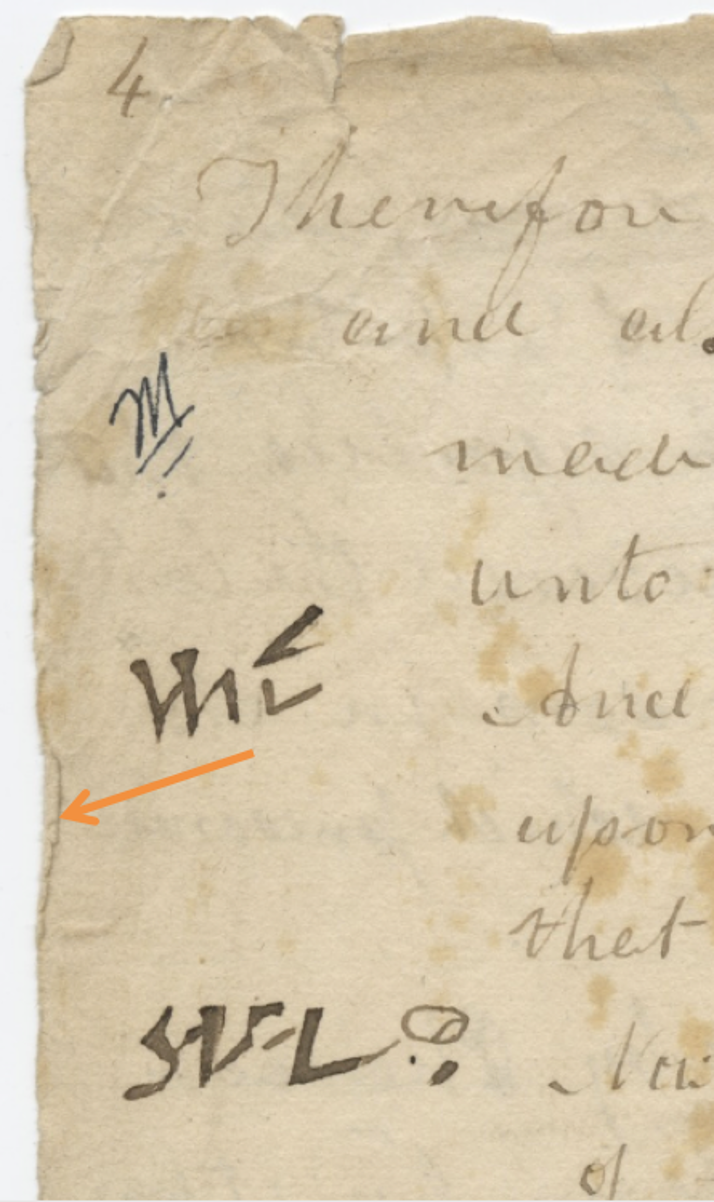

The volume editors, however, are not correct in their assertion that the second leaves in each manuscript were also joined. In what they call Book of Abraham Manuscript–A, the second leaf (comprising the third and fourth pages) has excess paper on the cut edge (which is the right edge of the recto or left edge of the verso) that has been folded over and is visible only from the verso. This material (approximately 1 mm wide in the photograph) appears along the left-hand edge between 3.5 and 5 cm from the top edge in the photograph.54 A portion of the corresponding image from the Joseph Smith Papers website is shown in Figure 1 with an arrow marking the folded-over excess paper. No corresponding lack of paper, or nick, appears in any potentially corresponding edge of the second leaf of Book of Abraham Manuscript–B as would be necessary if the second leaves also joined.55 Contrary to the assertions of the volume editors, these two leaves were not originally joined.

[Page 145]Even if the two successive leaves were joins, it would support the simultaneous dictation theory only if the page usage were the same for both scribes. But it is not. Warren Parrish has a larger hand and makes use of different margins than Frederick G. Williams. Williams has 41 lines on his first page, while Parrish only has 30. Thus Parrish was on the second page (verso of the leaf) at the same place in the text where Williams was on only his 19th line of the first page. At the place in the text when Parrish began his second leaf, Williams still had not finished his first page. At the place in the text where Williams was ready for his second sheet of paper, Parrish was almost done with his second sheet. Had the second sheet joined, it probably would have been coincidence. In other words, this argument is not necessary for the simultaneous dictation theory to be true. It would count as evidence for the theory only if it were true. Since it is not, it is simply irrelevant.

One suspects that the volume editors have confused page and leaf. This occurs elsewhere in the volume where the page count is given for a document rather than the leaf count.57 Because a leaf has two sides, or pages, and the first leaf is a join, perhaps the volume editors mistook the fact that the first two pages in each manuscript necessarily join because the pages are two sides of two leaves that join and either through confusion or mistake changed this to a statement about the first two leaves joining. The assertion shows that they were looking at photographs rather than the originals.

Just because the second proposed join is incorrect does not, in and of itself, mean that the simultaneous dictation theory is false. It just means that the volume editors cannot use this to bolster their theory.

Summary

In summary, the evidence that the volume editors have adduced for a simultaneous dictation does not prove their case. Looked at in the fuller picture of what Joseph Smith was doing in July through November 1835, there is no time when both Parrish and Williams were known to serve as scribes together. If they did, they are known to be working on other [Page 146]projects. Even if they did, the theory does not account for all the time when Parrish served as a scribe in the translation after the alleged event.

The Use of the Grammar and Alphabet

The volume editors insist that Joseph Smith worked on the book titled Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,58 and that book was a source for the Book of Abraham. The volume editors treat the book as though it were a single coherent document. It does seem to have been intended as an attempt to make a coherent document, but the manuscript also indicates it was executed in a number of discrete sessions where the bulk of the text was written and then a few pages were skipped to write another section. The individual sections are each within the range of known scribal work for a single section:

| Document Label | Written Pages | Blank Pages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grammar and Aphabet [sic] of the Egyptian Language | 7 | 26 | JSPRT4, 116–29 |

| Bethka | 1 | 0 | JSPRT4, 130–31 |

| Egyptian Alphabet fourth degree | 3 | 6 | JSPRT4, 132–37 |

| Bethka | 1 | 0 | JSPRT4, 138–39 |

| Egyptian Alphabet third degree | 2 | 6 | JSPRT4, 140–43 |

| Egyptian Alphabet Second Degree | 4 | 11 | JSPRT4, 144–51 |

| Bethka | 1 | 0 | JSPRT4, 152–53 |

| Egyptian Alphabet first degree | 3 | 15 | JSPRT4, 154–59 |

| Second part 5th Degree | 4 | 12 | JSPRT4, 160–67 |

| Second part 4thDegre | 2 | 22 | JSPRT4, 168–71 |

| Second part of 3rd Degree | 2 | 22 | JSPRT4, 172–75 |

| Second part 2nd Degree | 2 | 22 | JSPRT4, 176–79 |

| Second part of the Alphabet 1d Dgree | 2 | 38 | JSPRT4, 180–83 |

The volume editors assert that “some evidence indicates that material from the Grammar and Alphabet volume was incorporated into at least one portion of the Book of Abraham text in Kirtland.”59 They repeat this assertion later: “Some characters and elements from the definitions in the Egyptian Alphabet documents were incorporated into the Grammar and Alphabet volume, and a few were then copied into the Book of Abraham.”60 They neglect, however, to supply that evidence.

[Page 147]A truly puzzling issue arises when the editors claim that “This prefatory material [Abraham 1:1–4] contains the most similarities to the definitions in the Grammar and Alphabet volume and was therefore also likely connected to JS’s study of the Egyptian language.”61 This is footnoted to a reference,62 which refers the reader to another page in the volume which contains nothing to substantiate that the beginning verses of the Book of Abraham have anything to do with the Grammar and Alphabet.63 It is only when this claim is repeated (“The prefatory material inscribed by Phelps is closely related to the English explanations of characters found in the Grammar and Alphabet volume”64) that an actual usable reference is provided,65 but the assertion still begs the question of which document is the original and which is the copy. I will argue that the volume editors have it backwards.

Two documents containing significant portions of identical wording certainly raise the question of literary influence. One document may be influenced by another, or both could be influenced by a third source. For example, in Noah Webster’s The American Dictionary of the English Language, under the definition of the term accord, the phrase “My heart accordeth with my tongue” appears.66 This exact phrase, “my heart accordeth with my tongue,” also appears in a play by William Shakespeare.67 Following the volume editors’ line of thinking, one could erroneously conclude that Shakespeare obviously used this dictionary in producing his play and quoted the line from it. Of course, this specious line of reasoning ignores two things. The first is that Shakespeare’s play appears over two hundred years before Webster’s dictionary. The second is that dictionaries and other language reference works tend to quote from actual examples of earlier works. So in the case of the Grammar and Alphabet and the Book of Abraham, the question arises as to whether it is more likely that in composing a language reference work, the compilers would quote a phrase from a previous translation out of context or that in composing a work, that an entire phrase from a dictionary would be quoted and seamlessly make sense in the passage. [Page 148]The latter is a much harder thing for an author to do, so the former is the more likely direction of influence.

Authorship

The volume editors claim “the scribes gradually ceased work on the Egyptian Alphabet documents. After completing about four pages, JS and his clerks abandoned this project, moving on to work on the Grammar and Alphabet volume.”68 Without supplying any evidence, they simply beg the question of whether Joseph Smith was involved in the creation of the Grammar and Alphabet. They repeat this assertion later: “The Grammar and Alphabet volume was one piece of a larger attempt to understand the Egyptian language, which was in turn part of a larger effort by JS to study ancient languages.”69

This assumption is carried over to other parts of the text: “it appears that at the time Phelps stopped work on the Grammar and Alphabet volume in Kirtland, JS and his associates felt their work in studying an Egyptian language system was not finished.”70 The Book of Abraham manuscripts were, according to the volume editors, “also related to JS’s efforts to study the Egyptian language.”71

The tendency of the volume editors to assign work by Phelps to Joseph Smith continues in their discussion of a letter that Joseph Smith asked Phelps to ghostwrite for him:

Several months later, on 13 November 1843, JS and William W. Phelps drew on the Grammar and Alphabet volume in a letter to sometime Mormon supporter James Arlington Bennet. In the letter, JS and Phelps included several phrases in other languages, including an allegedly Egyptian passage based on the Grammar and Alphabet: “Were I an Egyptian,” the letter stated, “I would exclaim= Jah oh=ah: Enish-go=an=dosh. Flo-ees-Flo-isis.”72

This is not the way Joseph Smith talked about the letter in his journal. In his journal, Joseph Smith said he “gave instruction to have it [a letter from James Arlington Bennet] answerd” by W. W. Phelps in his name.73 Phelps spent three or four days working on the draft. [Page 149]On the morning of 13 November 1843, “Phelps read [the] letter to Jas A Bennet. & [Joseph Smith] made some correcti[o]ns.”74 It is clear from the journal that Joseph Smith considered the work that of W. W. Phelps.

Timing

When the volume editors claim that “Some characters and elements from the definitions in the Egyptian Alphabet documents were incorporated into the Grammar and Alphabet volume, and a few were then copied into the Book of Abraham,”75 they posit an order of the documents: The Egyptian Alphabet documents come first. The Grammar and Alphabet comes second. The Book of Abraham manuscripts come third. The evidence from the Joseph Smith Papers contradicts the volume editors’ posited order.

Before proceeding with that evidence, it is worth noting another error the volume editors make in arguing for the order of the documents. They claim: “Characters from the Book of Breathing for Horos, the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar and Alphabet volume, and possibly other unknown sources were copied in the margins” of manuscripts of the Book of Abraham.76 The volume editors give no reason other than their underlying assumptions as to why the copying could not have gone the other direction, namely, from the manuscripts of the Book of Abraham to the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar and Alphabet. This is not a one-time mistake. In discussing Book of Abraham Manuscript A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2, the volume editors state: “Along the left margin of each page of this version are characters copied from the surviving fragments of the papyri, from the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar and Alphabet volume, and possibly from other unknown sources.”77 When introducing Book of Abraham Manuscript B = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 3, the volume editors claim: “Characters from the Book of Breathing for Horos, from the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar and Alphabet volume, and possibly from other unknown sources were copied in the margins.”78 In the introduction to Book of Abraham Manuscript C = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 1, the volume editors say: “Characters from the Book of Breathing for Horos, from the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar [Page 150]and Alphabet volume, and possibly from other unknown sources were copied in the margins.”79 While the assumption of a particular direction of copying is an important issue, the volume editors have actually made a greater error here. The characters in the margins of the Egyptian Alphabet document come from Joseph Smith Papyrus I, while the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts come from Joseph Smith Papyrus XI, so the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts cannot have been copied from the Egyptian Alphabet documents. The characters in the Grammar and Alphabet come from a variety of sources but mostly from Joseph Smith Papyrus I, so they cannot be the source of the characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts.

The volume editors insist this manuscript was also produced between July and November 1835. They assert that “Phelps likely began inscribing Grammar and Alphabet material in this volume sometime between July 1835 (when the Egyptian Alphabet documents were first drafted) and 1 October 1835 (when JS’s journal mentions that JS, Oliver Cowdery, and William W. Phelps worked on ‘the Egyptian alphabet,’ which could refer either to the Grammar and Alphabet volume or to the Egyptian Alphabet documents).”80 The volume editors reinforce this in a footnote, claiming the reference to “the system of astronomy” in the journal “may refer to the significant material in the Grammar and Alphabet volume that discusses a planetary system.”81 They claim that “the first through fourth degrees of the first part of the Grammar and Alphabet volume begin with the title ‘Egyptian Alphabet,’ perhaps indicating that members referred to the volume that way.”82 They further claim “that those transliterations [of Hebrew words] are absent from the Grammar and Alphabet volume suggests that work on the Grammar and Alphabet was completed before church leaders began studying Hebrew in early 1836.”83

If finding Parrish and Williams together in the presence of Joseph Smith is problematic, it is nothing compared with having Joseph Smith working with Phelps at this time. Joseph Smith’s journal records five such instances.

On 1 October 1835, Joseph Smith labored with Oliver Cowdery and W. W. Phelps on “the Egyptian Alphabet.”84 These are the same three [Page 151]individuals in whose handwriting are three documents all labeled “Egyptian Alphabet.”85 Since both the titles and handwritings match, there is no reason to hypothesize, as the volume editors do, that the entry “could refer either to the Grammar and Alphabet volume or to the Egyptian Alphabet documents.”86 The Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language matches neither in the title nor the handwriting and thus is not a possibility. The volume editors state that “Characters, transliterations, and definitions from the Egyptian Alphabet documents were later copied into the Grammar and Alphabet volume.”87 I concur with this statement. This dates the Grammar and Alphabet after the Egyptian Alphabet documents and, by logical extension, should date the Grammar and Alphabet after 1 October 1835.

On 23 October 1835, Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, Hyrum Smith, John Whitmer, Sidney Rigdon, Samuel H. Smith, Frederick G. William and W. W. Phelps were involved in a prayer meeting.88 Translation does not seem to have been on the agenda.

On 29 October 1835, while Joseph Smith and Warren Parrish were visiting Frederick G. Williams to fetch “my large journal,”89 Edward Partridge and W. W. Phelps came together and the four “examined the mumies,” after which Joseph Smith and Parrish “returned home and my scribe commenced writing in <my> journal a history of my life.”90 This document survives, and from the handwriting and the description left in the journal, we know that Parrish wrote less than a page on that day.91

On Sunday, 1 November 1835, Joseph Smith was in the congregation when W. W. Phelps preached.92 A large amount of Church business was transacted on the occasion, but translation is not listed.

[Page 152]On Sunday, 8 November 1835, Joseph Smith publicly rebuked W. W. Phelps and John Whitmer before the congregation, and “they made satisfaction the same day.”93

To these journal entries, we can add the following known instances of W. W. Phelps’s serving as Joseph Smith’s scribe:

He served as a scribe on documents dated to 1 June 1835,94 2 June 1835,95 and 15 June 1835.96 He apparently worked on the translation in July, as he wrote his wife in September of that year: “Nothing has been doing in the translation of the Egyptian Record for a long time, and probably will not for some time to come.”97 He is not otherwise known to have served again as a scribe until 6 August 1836.98

So was the work in July on the Grammar and Alphabet? Phelps calls it “the Egyptian Record,” not an alphabet or a grammar, and says it was a translation, not an analysis. This makes it unlikely that it was the Grammar and Alphabet, especially since there is a better candidate for this document. One of the manuscripts of the Book of Abraham is in the handwriting of W. W. Phelps.99 Furthermore, it is specifically called a “Translation.”100 Joseph Smith used the same language when he published the Book of Abraham, calling it “A Translation of some ancient Records that have fallen into our hands.”101 This manuscript was started in the handwriting of Phelps and stops at the point where the other two Kirtland period manuscripts begin. The most likely explanation is that Phelps wrote the translation of this portion “a long time” before September, likely in July, and the other manuscripts started on separate sheets of paper, picking up where Phelps left off. Later, Parrish copied these manuscripts onto the one started by Phelps.

This accounts for all the known instances in 1835 and 1836 when Phelps served as a scribe for Joseph Smith. There is no point in time, especially in the time period specified by the volume editors, when Phelps could have taken the Grammar and Alphabet in dictation [Page 153]from Joseph Smith. Yet the Grammar and Alphabet is in the handwriting of W. W. Phelps. The conclusion must be that either the document was not produced when the volume editors claim it was produced, or Joseph Smith was not involved in its authorship, or both. At one point the volume editors refer to “Phelps used material from the Egyptian Counting document in some of the definitions in” the Grammar and Alphabet.102

Letters of W. W. Phelps to his wife, Sally, give indications of what he had been doing. Although Phelps wrote on a weekly basis,103 not all of the letters have been preserved. On 11 September 1835, Phelps wrote that he was “now revising hymns for a hymn Book.”104 On 16 September 1835, Phelps noted that the first copies of the Doctrine and Covenants had come back from the bindery: “We got some of the Commandments from Cleveland last week; I shall try to send one hundred copies to the Saints this fall by Br. Wm Tippets. He starts next week. I know there will be one hundred Saints who will have their dollar ready, when he arrives, for a Book, we put them at a dollar in order to help us a little.”105 On 27 October 1835, Phelps told Sally that “We shall begin to study Hebrew this winter, according to our present calculations.”106 So they were already making plans to learn Hebrew. Phelps was also not satisfied with using the bindery in Cleveland and so noted that “We are also establishing a bindery to bind our own books.”107 By 14 November 1835, the school had already started:

The school has commenced under the charge of President Sidney Rigdon as teacher. I shall not be able to go much, if any; President Cowdery has gone to New York to purchase tools for a book bindery and to secure some Hebrew books so that we may study Hebrew this winter. My time and that of President John Witmer [sic] is all taken up in the printing office. We have, when all are in the office, three apprentices and four journeymen, and we shall have to employ more men, as our work is so far behind. We have 18 numbers of the old “Star” [Evening and Morning Star] to print [Page 154]yet, and the “Messenger and Advocate” has been and is yet five or six weeks behind its time; and the hymn book is not likely to progress as fast as I wish, but we are all kept busy and have faith that the Lord will eventually bring about all things for our own good and his name’s glory.108

Even on 5 January 1836, Phelps was able to tell Sally, “The Hebrew school has commenced in one of the attic school rooms in the Lord’s House.”109 This frustrated Phelps a bit: “I want to study Hebrew, and I have not as yet been able to begin.”110 Ironically, Joseph Smith was studying Hebrew. The printing office kept Phelps so busy that he found he had to take “time when others sleep to write” on other projects.111

The volume editors do not seem to appreciate that Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, Frederick G. Williams, and W. W. Phelps were all very busy. The whole reason that Warren Parrish was hired as a scribe was that the other brethren were too busy to serve as scribe.

The volume editors may have done Joseph Smith a great disservice by assigning the Grammar and Alphabet to him. They have standard ways of indicating disputed documents, and they should have used them here.112

Comparative Chronology

To see the difference that a more accurate view of the documents gives to the translation of the Book of Abraham, I will compare my chronology (based on the manuscript evidence) with that proposed by Edward Ashment, Brent Metcalfe, Dan Vogel, Brian Hauglid, and Robin Jensen (hereafter AMVHJ) and promoted by Hauglid and Jensen in their volume of the Joseph Smith Papers. Although by their own admission, Hauglid and Jensen derived their theory from critics of the Church, I do not address the individual claims of those critics, but instead focus only on the theory as Hauglid and Jensen articulate it in JSPRT4.

[Page 155]Both theories require certain assumptions and hypothesize events that are not recorded. I will make explicit these assumptions and hypothesized events.

The AMVHJ hypothesis is based on their theoretical approach to the translation (most of the group may lack significant experience with translation). They suppose that Joseph Smith first copied a character, then constructed an alphabet, then wrote a grammar, then translated the Book of Abraham. Many people who learn languages first learn the signs and grammar, and then start translating, but those who decipher languages decipher first and then write the sign lists and grammar. For the AMVHJ hypothesis, the theory takes precedence over the evidence, and if the evidence does not match the theory, then it is set aside, or ignored.

My chronology proceeds on the basis of two assumptions, which I derive from evidence. Based on known scribal output from Joseph Smith’s scribes at the time, I assume that a translation session will produce four to six pages per session, with an absolute maximum of eight pages. Based on the extant manuscripts, this equates to about 45 verses per session. Compared to the translation of the Book of Mormon six years earlier in 1829,113 this is a slower pace.

July 1835

Evidence: The only contemporary record of events is the letter of W. W. Phelps to his wife dated 19–20 July 1835:

The last of June, four Egyptian mummies were brought here; there were two papyrus rolls, besides some other ancient Egyptian writings with them. As no one could translate these writings, they were presented to President Smith. He soon knew what they were and said they, the “rolls of papyrus,” contained the sacred record kept of Joseph in Pharaoh’s court in Egypt, and the teachings of Father Abraham. God has so ordered it that these mummies and writings have been brought in the Church and the sacred writing I had just locked up in Brother Joseph’s house when your letter came, so I had two consolations of good things in one day. These records of old times, when we translate and print them in a book, will make a good witness for the Book of Mormon. There is nothing [Page 156]secret or hidden that shall not be revealed, and they come to the Saints.114

A later reminiscence, probably also from Phelps written as though from Joseph Smith, reads:

Soon after this, some of the Saints at Kirtland purchased the mummies and papyrus, a description of which will appear hereafter, and with W. W. Phelps and Oliver Cowdery as scribes, I commenced the translation of some of the characters or hieroglyphics, and much to our joy found that one of the rolls contained the writings of Abraham, another the writings of Joseph of Egypt, etc. — a more full account of which will appear in its place, as I proceed to examine or unfold them.115

My Theory: I posit two translation sessions during this time; three is preferable. In the first session, the portion of Book of Abraham Manuscript C = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 1 in the handwriting of Phelps was produced. In the second session, a manuscript paralleling Book of Abraham Manuscript A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2 was produced; this would also have been in the hand of Phelps, or possibly Cowdery. It would have started on a separate sheet of paper. Its existence is inferred from the lengthy dittography (a repeated portion of text) on the last page of Book of Abraham Manuscript A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2. Lengthy dittographies are otherwise attested in Joseph Smith’s scribes at the time only in copied texts, not in dictated passages.116 Since, by my dating, neither manuscript in Parrish’s handwriting (Book of Abraham Manuscript B = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 3 and Book of Abraham Manuscript C = CHL ms. 1294 fd.1) existed to be copied from the existence of another manuscript, and a translation session to produce it must be deduced. One further translation session would bring the translation to Abraham 3:28. This is indicated because the term Shinehah from Abraham 3:13 appears as a code name for Kirtland in the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.117 Other translation sessions could have possibly occurred and further material produced, but my theory does not require them.

[Page 157]Some might hypothesize that the term Shinehah was borrowed into the Book of Abraham from its use in the Doctrine and Covenants. This hypothesis assumes that the Book of Abraham is a modern fictional work written by Joseph Smith. The assumption, though unstated, is essential for the argument to be comprehensible. The problem with the assumption is that this term in the Book of Abraham is a known Egyptian term. For at least two decades this term has been known to be an Egyptian term for the path of the sun around the earth, the ecliptic,118 which matches with the Book of Abraham’s description that “this is Shinehah, which is the sun” in the context of the movement of heavenly bodies (Abraham 3:13). A look at the ancient Egyptian usage of the term provides a more informative view of its usage. The ancient Egyptian term is either written mr-n-ḫꜣ or š-n-ḫꜣ. The pronunciation of the latter can be reconstructed as *šī-ne-ḫaʾ.119 The spread of usage of the spellings shows the following (using only datable sources120):

| Pharonic Reign | Approximate Date | mr-n-ḫꜣ | š-n-ḫꜣ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unas | 2321–2306 BC | 2 (100%)121 | |

| Teti | 2305–2279 BC | 12 (100%)122 | |

| Pepi I | 2276–2228 BC | 23 (100%)123 | |

| Merenre | 2227–2217 BC | 9 (100%)124 | |

| [Page 158]Pepi II | 2216–2153 BC | 13 (62%)125 | 8 (38%)126 |

| Dynasty IX preunification | 2066–1970 BC | 3 (100%)127 | |

| Mentuhotep II | 1970–1959 BC | 3 (100%)128 | |

| Sesostris I or Amenemhet II | 1920–1843 BC | 1 (100%)129 |

As the table shows, there was a change in the use of the term from mr-n-ḫꜣ to š-n-ḫꜣ that took place at the end of the Sixth Dynasty. The term disappears at the end of the Middle Kingdom and is not attested later. While the majority of the Middle Kingdom uses are not more precisely datable, only two uses from the Middle Kingdom that are not more precisely datable use the archaic form; the rest use the later form. This term is used only in Abraham’s day. If one accepts that the Book of Abraham is ancient, then the simplest explanation is that the Doctrine and Covenants borrows from the Book of Abraham. If one argues that the Book of Abraham borrows from the Doctrine and Covenants, then one assumes the Book of Abraham is modern, but one must still explain how it contains an authentic Egyptian term whose existence was unknown to Western scholarship until 1882.130

My theory requires three sessions and two documents produced, both Book of Abraham manuscripts, one of which is no longer extant. With two sessions, the first would cover Abraham 1:1–4; the second would cover Abraham 1:5–2:18. A third session would bring the translation to Abraham 3:28. This would be the equivalent of nine pages of translation.

AMVHJ Theory: July was a very busy month in the AMVHJ theory. Hauglid and Jensen claim that “In early July 1835 in Kirtland, Ohio, JS and other individuals purchased a collection of Egyptian artifacts from Michael Chandler.”131 Then “Oliver Cowdery, William W. Phelps, and perhaps another clerk prepared two notebooks, into which they copied Egyptian characters from the papyri that had been brought to Kirtland, [Page 159]Ohio, by Michael Chandler.”132 They claim that “both were likely created in early July 1835 — after Chandler arrived in Kirtland but before the papyri were purchased — presumably to help JS and others study the content of the papyri.”133 “Smith, Phelps, and Cowdery ‘commenced Translation of some of the Characters’ presumably soon after the papyri and mummies were purchased. According to Richards, the work of ‘translating an alphabet to the Book of Abraham, and arrangeing a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients’ continued through the end of July.”134 Although they note that “there is no evidence Joseph Smith read, approved, or corrected this passage”135 in a later narrative written by Willard Richards, who was not present. They also claim that “Likely in summer 1835, JS and his clerks created three loose-leaf documents bearing copies of Egyptian characters and vignettes.”136 Given that Joseph Smith was away in August, the only summertime available was in July. They likewise posit that the copy of the hypocephalus should also be dated “to the Kirtland era” possibly as early as July 1835.137 The volume editors also claim that July 1835 was “when the Egyptian Alphabet documents were first drafted.”138 They also claim that “JS and his scribes evidently worked on the Book of Abraham in summer 1835. JS’s history places the translation effort soon after the acquisition of the Egyptian artifacts in early July 1835.”139 They do not identify any specific translation activity.

According to the AMVHJ theory, Joseph Smith and his scribes produced nine documents in July 1835:

- “Valuable Discovery” = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 6.140

- Notebook of Copied Egyptian Characters = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 7.141

- Copies of Egyptian Characters-A = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 8.142

- Copies of Egyptian Characters-B = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 9.143

- [Page 160]Copies of Egyptian Characters-C = Papyrus Joseph Smith IX.144

- Copy of Hypocephalus = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 5.145

- Egyptian Alphabet-C = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 3.146

- Egyptian Alphabet-B = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 4.147

- Egyptian Alphabet-A = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 5.148

Together they total 22 pages. Based on the average amount that scribes seem to be doing per session, then it would conservatively have taken at least five translation sessions.

There is actually a major problem with this theory. The Egyptian Characters on Copies of Egyptian Characters–C was on the backing paper when the papyrus fragments were mounted. But Copies of Egyptian Characters-B = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 9 is actually a copy of the papyrus fragment (Papyrus Joseph Smith IX) mounted on Copies of Egyptian Characters–C, but shows that the fragment was much larger at the time it was copied.149 So the characters on Copies of Egyptian Characters–C must have been copied much later than Copies of Egyptian Characters-B= CHL ms. 1295 fd. 9, after the bits of papyrus were lost. Because proponents of the AMVHJ theory cannot read the characters copied, they did not notice this problem.

August–September

In August “JS traveled from Kirtland to Michigan to visit Saints” returning on the twenty-third.150 On 9 September Phelps wrote to his wife saying that he hoped his letters “will be sufficient to keep every member in the way of duty till the “Doctrine and Covenants” arrive.”151 A week later he said that “We got some of the Commandments from Cleveland last week; I shall try to send one hundred copies to the Saints this fall by Br. Wm Tippets. He starts next week.”152 This indicates that [Page 161]the entire Doctrine and Covenants was in print by that time. This is important, because the Doctrine and Covenants uses Shinehah from the Book of Abraham as a code name for Kirtland.153 This would indicate that Abraham 3:13 had been translated before that point.

Phelps also wrote his wife on 11 September 1835: “Nothing has been doing in the translation of the Egyptian Record for a long time, and probably will not for some time to come.”154 This shows that no translation had been done since Joseph Smith left for Michigan. It also shows that what they had worked on to that point was considered a “translation.” Up to this point, the only translation that Phelps had mentioned to his wife was “the sacred record kept of Joseph in Pharaoh’s court in Egypt, and the teachings of Father Abraham. … These records of old times, when we translate and print them in a book, will make a good witness for the Book of Mormon.”155

During August and September neither theory posits any translation. My theory accounts for the translation up to that point; the AMVHJ theory does not.

1 October 1835

Evidence: Joseph Smith’s journal records the following for this date: “This after noon labored on the Egyptian alphabet, in company with brsr O Cowdery and W W. Phelps: The system of astronomy was unfolded.”156

My Theory: The title of what the three men were laboring on is given as “the Egyptian alphabet.” I identify these with the three documents labeled “Egyptian alphabet” (CHL 1295 fd. 3–5).157 The three documents are in the handwriting of Oliver Cowdery, William W. Phelps, and Joseph Smith, the three people mentioned in the journal entry. All are four or five pages and so within the range of what was known to be produced in a single session.

Since the third chapter of Abraham had already been produced in July (as evidenced by the reference to it in the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants), there are two possibilities: If the system of astronomy is the explanations [Page 162]of Facsimile 2, then only 14 pages needed to have been produced at this point. If the system of astronomy refers to additional material we no longer have which would provide the promised content about the “knowledge of the beginning of the creation, and also of the planets, and of the stars, as they were made known unto the fathers” (Abraham 1:31), then we would have to increase the number of translation sessions in July.

AMVHJ Theory: The AMVHJ theory asserts that the journal entry “could refer either to the Grammar and Alphabet volume or to the Egyptian Alphabet documents.”158 The volume editors hypothesize that “the first through fourth degrees of the first part of the Grammar and Alphabet volume begin with the title ‘Egyptian Alphabet,’ perhaps indicating that members referred to the volume that way.”159 They claim that “Phelps likely began inscribing Grammar and Alphabet material in this volume sometime between July 1835 (when the Egyptian Alphabet documents were first drafted) and 1 October 1835,”160 but the material was still done by Joseph Smith because “the Grammar and Alphabet volume was one piece of a larger attempt to understand the Egyptian language, which was in turn part of a larger effort by JS to study ancient languages.”161 Apparently “the scribes gradually ceased work on the Egyptian Alphabet documents. After completing about four pages, JS and his clerks abandoned this project, moving on to work on the Grammar and Alphabet volume.”162

So the bulk of the Grammar and Alphabet is hypothesized to have been done on 1 October 1835. Since the Grammar and Alphabet comprises 34 pages of material, this would have been the largest single production session known for Joseph Smith in 1835 and 1836. And it is mostly in the handwriting of Phelps. Cowdery is not involved in the handwriting to the volume. What was he doing all that time when this phenomenal production was going on? Proponents of the AMVHJ theory do not say. For all the laboring that Oliver Cowdery did that day, according to the AMVHJ theory, there is nothing to show for it.

My theory posits 14 or 17 pages produced by three scribes on that day, whereas the AMVHJ theory posits twice as many at 34 pages produced by one scribe.

[Page 163]3–7 October 1835

Frederick G. Williams served as a scribe to Joseph Smith between the third and seventh of October 1835.163 On the last journal entry of that period, Joseph Smith recorded: “this afternoon recommenced translating the ancient records.”164

My Theory: The period when Frederick G. Williams served as a scribe is the best time to place the production of Book of Abraham Manuscript-A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2.165 While the recommencement of translation mentioned on 7 October 1835 could have simply been the occasion of copying the known manuscript in his handwriting, it might also have been a continuation of the Book of Abraham that had been produced in July. On the minimal end of things, that would put the translation of the Book of Abraham through about the end of Abraham 5.

AMVHJ Theory: The AMVHJ theory posits that essentially nothing happened during this time. Although the journal entry is noted,166 nothing particular is done with this information other than vaguely suggesting that this was somehow involved in the translation process. According to the AMVHJ theory, no actual translation of the Book of Abraham had yet been produced at this point.

8–28 October 1835

No mention of translation occurs during this time. Neither theory posits any specific translation during this period. My theory posits that because Joseph Smith lacked a scribe, nothing was done. The AMVHJ theory is vague about any translation occurring.

29 October 1835

On 29 October 1835 “Br W. Parish commenced writing for me.”167 This is the commencement of Warren Parrish’s involvement with Joseph Smith as a scribe. No manuscript in Warren Parrish’s hand should be dated before this date.

[Page 164]19–26 November 1835

This week is the time when the most translation activity takes place. These are the recordings from Joseph Smith’s journal:

19 November 1835: “I returned home and spent the day in translating the Egyptian records.”168

20 November 1835: “we spent the day in translating, and made rapid progress.”169

24 November 1835: “in the after-noon, we translated some of the Egyptian, records.”170

25 November 1835: “spent the day in Translating.”171

26 November 1835: “at home, we spent the day in transcribing Egyptian characters from the papyrus.”172

My Theory: The evidence is for four sessions of translation. I had conservatively estimated the previous session as ending at the end of Abraham chapter five. At the rate indicated by the scribal remains, 45 verses per session, and with an average of slightly more than 27 verses per chapter in the current Book of Abraham, the translation at the end of 25 November 1835 should be at about Abraham 11:18 in a book whose published version ends suddenly at Abraham 5:21. This is well beyond the published text of the Book of Abraham and is based, not on wishful thinking, but on the actual documented scribal activity of Joseph Smith’s scribes in 1835 and 1836.

Even if we went absolute minimalist on the production of the Book of Abraham, the W. W. Phelps portion of Book of Abraham Manuscript–C = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 1 would have had to be produced in July 1835. Book of Abraham Manuscript–A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2 would have been produced on 7 October 1835. If we assign the production of Book of Abraham Manuscript–B = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 3 to 19 November 1835 and the Warren Parrish portion of Book of Abraham Manuscript–C = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 1 to 20 November 1835, then Abraham 2:19–3:28 would have to be assigned to 24 November 1835 and Abraham 4:1–5:21 to 25 November 1835. All of the current Book of Abraham would have [Page 165]to fit in the Kirtland period, on the basis of known scribal practice and known translation dates. This minimalist scenario does not account for all of the evidence and so is not to be preferred.

The activity on 26 November 1835 is given as “transcribing.” The only manuscripts that fit with transcribing are Copies of Egyptian Characters-A = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 8,173 and Copies of Egyptian Characters-B = CHL ms. 1295 fd. 9.174 It would make the most sense to assign these two documents to this date rather than July. Otherwise we need to hypothesize the existence of transcription documents we no longer have.

AMVHJ Theory: According to the AMVHJ theory, “five more times in late November, Smith and likely Phelps and Parrish were occupied either in ‘translating’ or in ‘transcribing Egyptian characters from the papyrus.’”175 Since the AMVHJ theory insists that Book of Abraham Manuscript–A = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 2 and Book of Abraham Manuscript–B = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 3 were dictated simultaneously, the only day that might have been possible is 19 November 1835, and only if Frederick G. Williams spent the whole day with Joseph Smith and not just the temple inspection in the morning. On this day, according to the AMVHJ theory, both Book of Abraham manuscripts were produced simultaneously. If the session on 20 November 1835 was spent with Warren Parrish copying the same manuscript onto Book of Abraham Manuscript–C = CHL ms. 1294 fd. 1 (ignoring that Joseph Smith described them as having “made rapid progress” on this date),176 then according to the AMVHJ theory the next three sessions produced nothing in spite of the documentation in the journals, since the AMVHJ theory insists that nothing after Abraham 2:18 was dictated in Kirtland, and the rest of the Book of Abraham was dictated in Nauvoo.

This creates an unacknowledged problem for the volume editors. Even the volume editors commenting on Parrish’s statement that “I have set by his [Joseph Smith’s] side and penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks as he claimed to receive it by direct inspiration from Heaven,”177 note that “while it is possible Parrish was speaking of the work on the Egyptian Alphabet documents or the Grammar and [Page 166]Alphabet volume, the majority of Parrish’s scribal work was on the Kirtland-era Book of Abraham manuscripts.”178 For at least one of those manuscripts they claim that “it appears that Parrish copied from his earlier version of the Book of Abraham.”179 The other manuscript, as I have shown, is more readily explained as a corrected copy. This means that the volume editors do not really have Parrish recording any “translation of Egyptian Hieroglyphicks” from the mouth of Joseph Smith, contrary to both Parrish’s statement and Joseph Smith’s journal.

The project ended here because “JS’s journal does not mention work on the Egyptian-language project after late November 1835.”180

1842

The next evidence for translation of the Book of Abraham occurs in 1842 when the Book of Abraham was being published. Though some days mentioned giving “instructions concerning the cut for the altar & gods in the Records of Abraham,”181 “explaining the Records of Abraham,”182 “correcting the first plate or cut. of the Records of father Abraham,”183 or “exhibeting the Book of Abraham,”184 fewer journal entries actually mention translation. There are two. On the 8 March 1842, the entry reads: “Commenced Translating from the Book of Abraham, for the 10 No of the Times and seasons — ”185 The 9 March 1842 entry reads: “in the afternoon continud the Translation of the Book of Abraham. … & continued translating & revising. & Reading letters in the evening Sister Emma being present in the office.”186

Joseph Smith also mentioned his translation activities in a letter written to Edward Hunter on 9 March 1842: “I am now very busily engaged in Translating, and therefore cannot give as much time to Public matters as I could wish, but will nevertheless do what I Can to forward your affairs.”187

[Page 167]My Theory: The printed version of the Book of Abraham from 1842 differs from the Kirtland manuscripts of 1835, which shows instances of revision for publication, including the addition of the “and the god of Korash” in Abraham 1:6 and 1:17, the spelling of the god “Libnah” in the same verses, and the standardization of the spelling of “Elkenah.” These are instances of the “revising” mentioned in the 9 March 1842, but since these changes had occurred in sections of the Book of Abraham that had been published previous to 9 March, they show revisions in translations. Retranslating and revising is not uncommon in translations. The document in Doctrine and Covenants 7 also shows Joseph Smith retranslating and revising his translations.188 Because my theory already has this portion translated, there is no problem in there being revisions to the translation at this stage. Those revisions could hypothetically include revising the Hebrew transliterations to the then standard Hebrew transliteration system that Joseph Smith had learned from Sexias, though he could also have received them via revelation, as he had with Hebrew names that appear in the Book of Mormon. We cannot determine this without the manuscripts.