Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the seventh in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that Joseph could guess the name Nahom by chance alone, or that he could’ve gotten that location from a map.

The site of Nahom has been touted as solid archaeological evidence for the Book of Mormon, but it’s hard to know exactly how strong that evidence actually is. Could Joseph have guessed the name by chance? Could he have gotten the name from a contemporary map of Arabia? Some options are less likely than others. I estimate the odds that a Book of Mormon place name would match any of almost a hundred sites in the area around Nahom at just under 1 in 100 (p = .0097). By contrast, a liberal estimate of the likelihood that Nahom could have been gleaned from an available map is about 2 in 10,000 (p = .0001585). Regardless, Nahom provides meaningful—though far from overwhelming—evidence in the Book of Mormon’s favor.

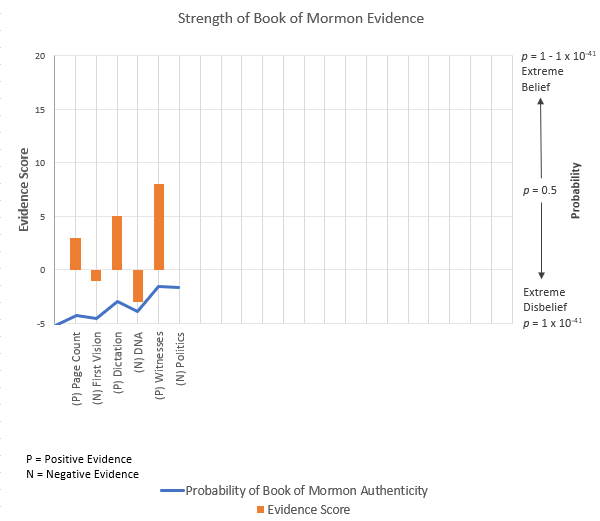

Evidence Score = 2 (the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon increased by two orders of magnitude—though it could be as high as four if we apply somewhat less conservative requirements)

The Narrative

When last we left you, our nineteenth-century skeptic, you were applying your skeptical worldview to the opening chapters of the Book of Mormon. You’ve now somehow managed to push past your seething contempt for Nephi’s murderous ways, running your eyes swiftly from line to line. You skim over an odd dream filled with seemingly opium-driven nonsense, only to shruggingly read through a second recitation of the same dream. You ignore familiar passages from Isaiah that you’re pretty sure match word for word with those from your own volume of the King James, which still lays open and dusty a few feet away on the table. Your vow to never touch the tome again keeps you from checking that for the moment, but you know sooner or later your curiosity will get the best of you. You hope in the meantime that such blatant plagiarism is an isolated anomaly.

Despite those hiccups, there’s something undeniably fascinating with the tale of this troubled Hebrew family. The narrative of brother against brother is simplistic, almost cliché, but compelling nonetheless. You also can’t help but notice some admittedly nice touches. You recognize the association of valleys with strength, rather than mountains, as a thoughtful and poetic Arabic idiom. It does strike you as strange, though, that someone would put reference to a continually flowing spring in the Arabian wasteland south of Jerusalem.

It occurs to you, though, that such details could be this Joe Smith’s undoing. You doubt highly that said Smith had travelled much past the Ohio, let alone to the far side of the world. If he was putting details this specific into his tall tale it wouldn’t take much more than a good map to prove him wrong. And the absurd details don’t stop there. A few pages later you read about a burial in “a place which was called Nahom,” a few weeks’ travel south of Jerusalem. Was there indeed such a place? Could one then turn and find a way to cross the seemingly infinite desert sands, as the book described?

If not, Smith might as well place his literary head in a noose right now, since sooner or later such pronouncements would hang him. But if so…well, if such things could be verified, it seems unlikely that one could get such geographic details correct simply through pure luck.

The Introduction

When critics of the Book of Mormon state, unequivocally, that there is “absolutely no archaeological evidence for the Book of Mormon," there’s at least one piece of evidence that they’re flatly ignoring. I’m not sure how anyone could take a look at the well-attested studies of the Nehem site, which is in the exact spot the Book of Mormon says it should be, and call that anything but evidence. Critics are nevertheless quite aware of the need to deal with this evidence, and seem committed to one of two propositions: either Nahom itself is a lucky guess, or Joseph had access to specialized maps that, at the time, were only available in distant locations.

It’s hard to know at first glance how likely either of these options are. It’s not easy to look at a name like Nahom and know how easy it would be to match with a stroke of guesswork, and it’s even harder to know whether it would be possible for Joseph to spend weeks traveling to dig through library stacks without leaving incriminating evidence. But those sorts of problems are exactly what Bayesian analysis is there to help us with.

As I’ve hinted at above, there’s a ton of different aspects of Lehi’s journey that could be pertinent to a Bayesian analysis, from the consistent use of the terms up and down in reference to travel to Jerusalem, to attestation of Hebrew temples built outside of the Holy Land, to viable locations for the Valley of Lemuel and Nephi’s Bountiful. But none of those seem to highlight the potential accuracy of the Book of Mormon narrative in the way Nahom does. So, for the purposes of this episode, we’ll be sticking to those three special consonants and the two (somewhat less relevant) vowels sandwiched between them.

The Analysis

The Evidence

When it comes to the location of Nahom, the facts are these: The Book of Mormon describes a location “which was called Nahom," a place where Lehi and his family bury Ishmael. This place, according to the book, is a long journey south-southeast of Jerusalem along a path near the Western coast of the Arabian peninsula. It is there, importantly, that they make a turn nearly east before arriving in a fertile coastal location, which they term Bountiful.

This described path generally aligns with the Frankincense trail, what is really a series of trails that snake through the arid, mountainous region on the west side of Arabia. The Frankincense trail makes a notable eastward turn a few hundred kilometers north of the southern coast, and follows what would’ve been the only practical path eastward through the desert in all of southern Arabia.

In 1997, archeologist Burkhard Vogt discovered an altar at a digsite in Yemen with an inscription of NHM. As the original written form of Hebrew did not include vowels, this inscription could have easily referred to a place called Nahom. This place lies close to the aforementioned eastern turn in the Frankinsence trail, and since this altar dated to 800 BC, it’s entirely plausible that Lehi and his party could have encountered this place on their journey through southern Arabia.

This Nahom, (or Nehem or Nehhm), was known to some outside of Arabia in the 1820s, but this knowledge wasn’t widely available. Maps containing reference to a town with that name, in that location, were only available at a few universities, the closest being Allegheny College, several hundred miles east of where Joseph lived or where he conducted his translation of the Book of Mormon. There is no evidence that he made a trip to any of these universities or would otherwise have access to maps detailed enough to contain reference to the relatively obscure settlement. Importantly, other than Jerusalem, none of the other places referenced in the Old World by the Book of Mormon (e.g., Shazer) are contained in those maps. If Joseph used any of those maps, he pulled only Nahom from them (though that would also be odd, since none of the available maps used Nahom as a spelling for the site), and nothing else.

Joseph also showed no knowledge that Nahom was a real place in Arabia at any point in his life. Joseph was keenly interested in archaeological evidence for the Book of Mormon, yet made no reference to Nahom as a place that could or would be confirmed as by archaeological efforts.

Scholars have also noted the potential for an interesting potential wordplay with the term Nahom, as the Hebrew meaning of the word is “mourning," which would fit well with the burial of Ishmael. Critics have noted, however, that the spelling of the actual site in Yemen uses a slightly different spelling (a hard h rather than a soft h). This doesn’t necessarily invalidate the wordplay (the spelling still could have reminded Nephi of the term), but we’ll give the critics the benefit of the doubt and not include the wordplay in our analysis (saving the concept of wordplay in the Book of Mormon for a later episode).

The Hypotheses

So, let’s take a look at our three hypotheses:

There was an authentic Lehi whose family visited the Nahom that corresponds with the present-day archaeological site—This theory is rather straightforward. The place name in the Book of Mormon is of ancient origin because ancient people recorded their visit.

Nahom is a place name invented by Joseph, and only corresponds to the present-day archaeological site due to chance alone—According to this theory, Joseph created the name as he would have created any other place name in the Book of Mormon, out of his own imagination. Based on this theory, we could assume that, due to chance, the name Nahom could have instead resembled any of the other allegedly invented names in the book.

Joseph chose the name of Nahom by inspecting available contemporary maps—This theory implies that the current evidence we have for the translation process is wrong, and that Joseph had certain resources available to him to help him obtain accurate information about ancient Arabia when piecing together his narrative. This would have involved a secret journey to a place with a map containing Nahom.

Why did the journey have to be secret? Couldn’t others have known about the journey and those resources and simply covered it up? Maybe, but it’s not a great maybe—as we’ve discussed previously, conspiracies are very very hard to maintain. Having to account for conspiracies would do the critics no favors, in this case or any other.

It’s also worth mentioning another, related theory. Rather than making up the name, it’s possible that Joseph could have pulled something similar to the name Nahum from the Bible, as is potentially the case for other (though far from all!) proper names in the Book of Mormon. Statistically, though, this theory is essentially indistinguishable from Joseph inventing the name—he would still be selecting the name basically at random from a large pool of potential options. The characteristics of Bible and Book of Mormon names probably aren’t identical, but they’re close enough that it wouldn’t matter for our analysis.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of an Authentic Lehi—Based on where we left off last time, our prior probability for an authentic Book of Mormon is sitting at a still unlikely p = 2.12 x 10-30. Here’s where we’ve been thus far:

PA1—Prior Probability of an Invented Nahom—It’s hard to know exactly how likely we might initially expect an invented Nahom to be relative to Joseph obtaining it from an existing map, but It’s clear that we should give the advantage to an invented Nahom, just in terms of parsimony. You need a lot fewer assumptions for Joseph to make up the name. He doesn’t even have to pack a bag, for heaven’s sake—he just has to sit there for a few seconds mulling it over. Based on that thinking, we’re going to divide the remaining probability by 10, and assign about 90% of it to an invented Nahom. That would leave us with a prior probability of p = .90.

PA2—Prior Probability of a Map-Originated Nahom—With about 10% of the remaining probability, that means our initial estimate for a likelihood of a map-originated Nahom is p = 0.1 – 2.12 x 10-30.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of an Authentic Lehi—Our question here is, how likely would we be to observe evidence for an authentic Nahom given an authentic Lehi? Now, it was never guaranteed that evidence for Nahom would ever show up even if it was authentic—it’s possible the name for it could have changed, or that ruins for it could have been damaged, or that it just plain never caught the interest of archaeologists. But, given time and improved methods, we would certainly expect evidence of this kind to turn up eventually. I’m comfortable treating this evidence as perfectly compatible with an authentic Lehi, with a consequent probability of p = 1.

CA1—Consequent Probability of an Invented Nahom—Here’s one case where the statistical problem at hand seems fairly straightforward. We have three Hebrew consonants, and all we appear to have to do is randomly select from the 22 consonants in the Hebrew language to try and guess each of those three. That probability all by itself is easy enough to calculate at p = .00009.

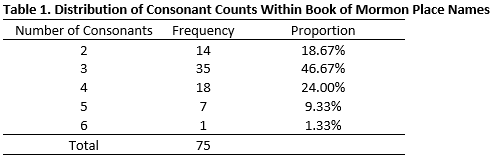

But matters are a little trickier than that. For one, Joseph wouldn’t have necessarily picked a name with three consonants. If you go through all 75 place names in the Book of Mormon (not counting Jerusalem), you discover that the number of consonants in the names varies from two to six—three is the most common, but it’s actually in the minority. That would mean multiplying the value above by .4667 to get the actual probability that a Book of Mormon place name would match NHM, with the resulting p = .000042. Here’s a table showing the distribution:

For these analyses I counted consonant sounds (e.g., sh; th) as a single consonant, double consonants (e.g., mm) as a single consonant, and I counted terminal silent h’s (e.g., as in “Antiparah”) as a separate consonant. If you feel that some other method would be more appropriate, feel free to let me know.

So that 4 in 100,000 chance is pretty low, and would constitute pretty strong evidence from a Bayesian standpoint. But that’s just the odds of guessing Nahom specifically. That brings up another important question—would Nahom be the only possible place where someone could have made a “nearly eastward turn” when in southwest Arabia? If not, then Nahom’s not the only potential target for a randomly generated place name, and we’ll need to increase our probability estimate accordingly. There are a bunch of different settlements relatively close to Nahom that could have just as easily substituted as a valid location for Ishmael’s burial, and that faithful scholars might have locked onto as a valid hit for the Book of Mormon.

What’s less clear is how big of a circle we would have to draw around Nahom to capture potentially valid sites, and I don’t think that’s something I could realistically determine as part of this essay. But we certainly can’t head too far north of Nahom, nor too far south—if the Frankincense trail is anything to go by, the path by Nahom is literally the only passable eastern trail in the entire peninsula—the wastes to the north are impassable, as is the rocky southern coastline. There’s no real east/west restriction that I can see, though—Lehi could’ve been essentially on the western coast itself and still made an eastward turn that cut through or near Nahom.

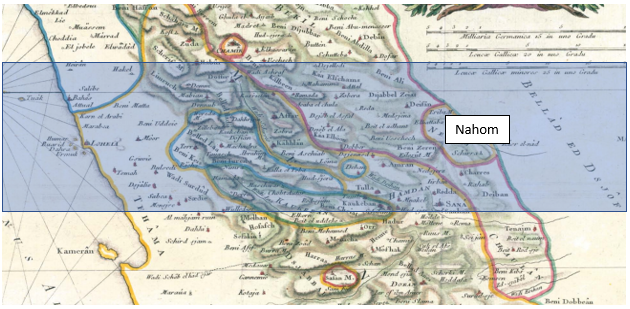

We’re going to be generous, as is our custom, and say that Joseph could have guessed at any location within 100 kilometers north and south of Nahom, as far west as the coast, and as far east as we can find any notable settlements in that range. (Want measurements in miles? Tough luck. I’m Canadian. Sorry.) We’ll use the most densely labeled map of the area from those available in 1830 (because they’re handy, not because they’d give a sense of what the area looked like in 600 BC), and make a list of all the labeled settlements within that range. That map has been included below, with the area of interest shaded. It gives us a list of 92 potential targets, for which we can calculate the odds of them being randomly guessed by Joseph, just as we did for Nahom (see the appendix for a table showing each). Once we do that, we can just sum those probabilities to get an estimate of how likely he would’ve been to hit any of those targets. That value happens to be p = .0097. Not as impressive as 4 in 10,000, but still somewhat difficult to pull off by chance alone.

Figure 1. A map of the area of Yemen containing Nahom, with a 200 km band highlighted.

CA2—Consequent Probability of a Map-Originated Nahom—If guessing at a valid Nahom-like site is unlikely, do we do any better by positing Joseph’s access to a contemporary map of Arabia? Since it’s very hard to imagine what good data on this question would even look like (how many other examples of proposed forgeries that made secret use of contemporary maps come to mind?), we’re going to have to make some educated guesses about how likely each step in that process would be, doing our best to bias those estimates in the critics’ direction.

Based on my understanding of this theory, there are seven unusual features in it that you would have to account for to align it with the data we have. Just for fun, I’m going to call them the Seven Seals of the Nahom Bayesian Apocalypse.

First, you have to get Joseph to a place with one of the Nahom maps without any of his family or friends making note of the trip. Second, he would have to access the map without any of the staff at the library noting his presence. Third, you have to account for the fact that he would’ve made the several-hundred-mile jaunt only to select a single location from a single map as a way of providing credence to his story. Fourth, you have to account for the change in spelling as none of the contemporary maps spell it the same way Joseph did—if you’re copying from a map, why change the spelling? Fifth, since none of the maps included information on the eastward turn, you have to account for him getting the turn right. Sixth, the city he chose would need to have existed at the purported time of Lehi—there’s no guarantee that would’ve been the case for a randomly selected location from the map. And seventh, you need to account for Joseph never mentioning Nahom again—why work so hard if no one would ever realize that the name matched a real-world location?

None of these items are necessarily impossible, but they’re definitely unexpected, and all of them should be independent of the others. I’m going to throw some numbers out there and you can tell me how unreasonable they are if you so desire.

The First Seal. The closest map that I can see that anyone’s posited that he might have had access to is 173 miles (from Harmony—now Oakland–Pennsylvania to Philadelphia, where a medical school at the time had one of the maps). A secret trip would be hard to pull off, and it would get harder the longer he was away. At a pace of 4 miles an hour, walking 10 hours a day, that round-trip would’ve taken him a little over a week. If he had even a 5% chance of getting caught each day of that trip, then the odds of him getting away with it would be just over half (p = .63401), and that’s without him actually spending any serious amount of time studying in the library.

The Second Seal. It seems fair to suggest that a young man from the frontier showing up out of nowhere at Amherst College would’ve turned some heads, and Joseph was later famous enough that you would think his arrival would’ve been reported at some point later in his life. Libraries in this era often required subscriptions in order to let people check out books, and it’s hard to imagine some uptight college librarian letting some random farm kid peruse the map section. I’m going to set the probability of him getting noticed by library staff at a very generous 50%.

The Third Seal. If someone is taking the time to enter some serious study of the geography of the Arabian peninsula, I would expect that they would have more to show for the fruits of their labor than a single, obscure location. As far as I’m concerned, I would only expect that to happen 10% of the time at the very most.

The Fourth Seal. Why pull a real location for use in your narrative and then immediately obscure that location with a change in spelling? In what universe does that make sense? A probability of 10% seems exceedingly generous here.

The Fifth Seal. There are approximately 2000 kilometers of the Arabian peninsula where Joseph could have had Lehi make that turn. If we use the same 200 km leeway we used for an invented Nahom, that would give Joseph a 10% chance of putting that turn in a reasonable location.

The Sixth Seal. Names change, people move, languages shift. The odds that a small settlement would remain settled over a period of 2500 years and also retain the same name seems really low on its face. I’ll still be a very nice person and give a 10% chance that a site that he chose could be dated to the right timeframe.

The Seventh Seal. And lo, the seventh seal was opened, and we all agreed that we don’t always know what Joseph Smith was thinking. We can’t say that it’s impossible for him to have concealed knowledge of Nahom, but hopefully we can all agree that not everyone would’ve done so if they were in his shoes. I’m assigning a probability of 50% for this one.

Multiplying the probabilities of the Seven Seals together, you get an estimated probability of producing the evidence listed above at p = .0001585. We’re going to go ahead and use that as the consequent probability of a map-originated Nahom.

Posterior Probability

With those probabilities calculated, we see where our Bayesian analysis lands us.

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the probability of an authentic Lehi, based on prior analyses, or p = 2.12 x 10-30)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the probability of observing the evidence we have given an authentic Lehi, which we set at p = 1)

PA1 = Prior Probability of an Invented Nahom (our initial estimate of the probability of an invented Nahom, or p = .9)

CA1 = Consequent Probability of an Invented Nahom (the probability that Joseph could have randomly matched the name of a settlement in the vicinity of Nahom, estimated at p = .0097)

PA2 = Prior Probability of a Map-Originated Nahom (our initial estimate at how likely Joseph could have been to get the name of Nahom off of a contemporary map, which we set at p = .1 – 2.12 x 10-30)

CA2 = Consequent Probability of a Map-Originated Nahom (the probability that Joseph could have accessed and used Nahom from a contemporary map while producing the evidence we observe, or p = .0001585)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our revised estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 2.12 x 10-30 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA1 * CA1) + (PA2 * CA2) | |

| PostProb = | (2.12 x 10-30 * 1) |

| ((2.12 x 10-30) * 1) + (.9 * .0097) + ((0.1 – 2.12 x 10-30) * .0001585) | |

| PostProb = | 2.41 x 10-28 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH / ((PA1 * CA1) + (PA2 * CA2))

Lmag = log10(1 / ((.9 * .0097) + ((0.1 — 2.12 x 10-30) * .0001585)))

Lmag = log10(1 / (.00873 + .00001585))

Lmag = log10(1 / .00875)

Lmag = log10(114.34)

Lmag = 2

Conclusion

There are a couple things that I glean from this analysis. The first is that critics should clearly prefer an “invented Nahom” scenario to a “map-originated” one. It’s easy to think that Joseph might have had access to a map, but making it concrete helps show how unrealistic that scenario would’ve been. Joseph hitting on it by chance is a way simpler—and way more likely—explanation. The second is that the strength of Nahom as evidence relies on something that I haven’t seen much attention paid to in scholarly circles, and that’s the number of other appropriate locations that Joseph could have hit on instead of Nahom. If there are 92 appropriate locations (which I would think is the high end) it’s not nearly as strong as if the Nehem site is the only possible spot. If Nehem really is the only viable target, it would move the needle about 3.5 orders of magnitude instead of 2, which, given our scale, would make the evidence about 50 times more informative from a Bayesian standpoint.

But either way, the evidence for Nahom is useful, but it’s far from a silver bullet. It’s not likely that Nahom could’ve been hit on by chance, but it’s not a statistical impossibility either. Its true strength, in my opinion, is as part of the rich tapestry of Old World evidence, the majority of which is outside the scope of this episode. Joseph could’ve—and should’ve–run afoul of the Old World in dozens of ways, but he simply doesn’t. Cataloguing those ways would be a much bigger project than the efforts I’ve put forward here. For the moment, though, we can be content with knowing that Nahom moves us a little further in the direction of an authentic Book of Mormon.

Skeptic’s Corner

Critics should probably be content with letting Nahom sit at a 2—given some of the evidence we have coming down the pike, they’ll soon have much bigger fish to try and fry. But if there’s a potential weakness here, it’s in the assumption that Joseph could’ve chosen any random combination of Hebrew consonants when putting together names. We know, for instance, that those names aren’t random—they tellingly avoid the consonants F, Q, V, W, X, and Y, some of which would have been improper within Semitic language conventions. Perhaps Joseph, with a bit of Hebrew expertise at his disposal (which he isn’t likely to have had at the time), could have limited his search space to just valid consonant combinations, potentially improving his chances of getting a direct hit. It would take a deeper dive than I have time for here to search out a set with potentially thousands of valid combinations, but if critics are determined to whittle down the strength of this evidence, they may be obliged to try.

Next Time, in Episode 8:

When next we meet, our skeptic will consider the efforts of boatbuilding and the perils of a transoceanic voyage.

Questions, ideas, and embarrassing anecdotes can be related to BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

| Potential Nahom Turn Targets | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | Place Name | Consonants | Probability |

| 1 | Ala | 1 | 6.1E-04 |

| 2 | Ali | 1 | 6.1E-04 |

| 3 | Uddeie | 1 | 6.1E-04 |

| 4 | Affar | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 5 | Attal | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 6 | Cheiat | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 7 | Chula | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 8 | Demm | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 9 | Loheia | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 10 | Loma | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 11 | Matta | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 12 | Moor | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 13 | Rodda | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 14 | Saedie | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 15 | Sana | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 16 | Torr | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 17 | Tulla | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 18 | Zeiat | 2 | 3.9E-04 |

| 19 | Achraf | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 20 | Achraf | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 21 | Amram | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 22 | Aschiab | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 23 | Asfal | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 24 | Attual | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 25 | Autar | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 26 | Bahas | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 27 | Charit | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 28 | Charres | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 29 | Chobt | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 30 | Degro | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 31 | Dehan | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 32 | Deiban | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 33 | Dennub | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 34 | Dobber | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 35 | Doffir | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 36 | Dofian | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 37 | Elboon | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 38 | Gsuvie | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 39 | Habir | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 40 | Hakel | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 41 | Hamada | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 42 | Heiran | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 43 | Iirban | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 44 | Karn | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 45 | Mabian | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 46 | Mahamma | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 47 | Marabea | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 48 | Nehhm | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 49 | Nunra | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 50 | Rahab | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 51 | Sabca | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 52 | Salibe | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 53 | Sand | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 54 | Schibani | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 55 | Schirra | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 56 | Sjenned | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 57 | Tauasch | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 58 | Temah | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 59 | Tsibu | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 60 | Tureiba | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 61 | Uschech | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 62 | Woreda | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 63 | Wulled | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 64 | Zilleba | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 65 | Zobera | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 66 | Zobra | 3 | 4.4E-05 |

| 67 | Abrahun | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 68 | Belled Laa | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 69 | Bulsedi | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 70 | Dsjalie | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 71 | Elbattaba | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 72 | Hamdan | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 73 | Kahhlan | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 74 | Kalbeen | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 75 | Kankeban | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 76 | Kaukeban | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 77 | Limruch | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 78 | Machadra | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 79 | Menejre | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 80 | Mnakeb | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 81 | Sanhan | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 82 | Surdud | 4 | 1.0E-06 |

| 83 | Ben Zeren | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 84 | Dahhrjin | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 85 | Elfchams | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 86 | Hadsjar | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 87 | Hudsjera | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 88 | Muschwar | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 89 | Nedsjera | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 90 | Redsjum | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 91 | Sdjelledi | 5 | 1.8E-08 |

| 92 | Kasr El-Nad | 6 | 1.2E-10 |

| Overall | 0.0097 | ||

“That viable competing explanations have proven so elusive should give the esteemed editors of the Journal of Archaeological Research some pause.”

There are two distinct issues here. First, what is the Book of Mormon. Second, where did it come from?

The Book of Mormon came to light in 19th century America and tells the story of a civilization that lasted from 600 B.C. to 421 A.D. that was obsessed with the specific religious issues of 19th America. The 19th century provenance of the Book of Mormon is beyond overwhelming. Trying to explain this fundamental fact to a true believer is like trying to explain water to a fish.

I happen to have the 337 page book “The Poems of John Keats” in front of me, with an introduction by Dr. Aileen Ward. Dr. Ward was a distinguished English professor who spent her entire career studying John Keats, a poet who died at the age of 25. From the introduction, Dr. Ward said, “The name of John Keats stands for the greatest miracle in English poetry. The miracles of genius breed doubt as well as faith: Shakespeare’s achievement has seemed so extraordinary to some of his readers that they have felt compelled to deny he could have written the works that bear his name. But what Keats accomplished in his brief lifetime would tax a skeptic’s faith still more. Sprung from the same kind of undistinguished parentage, given the same kind of middling education, trained for a career far less auspicious for poetry, Keats was dead at the age at which Shakespeare had only begun to try his hand at playwriting. It was within the space of a single year, his twenty-third, that he wrote almost all the work that has earned him his place in English poetry today.”

We could examine all of the minute elements that makes these and other works “miracles of genius.” We might not ever come up with a satisfying explanation for where they came from. But not understanding the details of how Keats wrote these poems isn’t evidence that they were written by an ancient Mesoamerican. Likewise with the Book of Mormon.

“that was obsessed with the specific religious issues of 19th America.”

We’ll get there, though Skousen makes a compelling argument that they aren’t as specific to 19th century America as you might hope, and the book deals with a great many religious and other thematic issues that appear quite specific to the ancient world.

“The miracles of genius”

As you appear to be using it here, the miracle of genius is a handwave rather than an explanation. In fact, it uses the lack of an explanation as supporting evidence in and of itself (and it seems to have that in common with great many conspiracy theories). What happens in Joseph’s case, though, when we make concrete the theory of Joseph’s supposed unfathomable genius? Does he have anything in common with these great literary geniuses? Would that genius be sufficient to produce the characteristics of the book itself? The answers to those questions appear to be, in reverse order, “no”, “no”, and “it falls flat on its face”.

“You misunderstand my argument.”

It sounds more to me like you’re just trying to bail out that argument, given all the leaks it seems to have sprung, but please continue.

“The author needed to find a plausible path to get his characters from a known location, Jerusalem, to the open ocean.”

You must be looking at a different map than I am, because from Jerusalem I can see a half dozen plausible paths to the open sea, almost all of which being clearer and more convenient from the perspective of a fraudlent author.

If that’s what you call a smoking gun, I should probably stop taking you seriously when you propose these kinds of supposed anachronisms.

“Do you find odd that the founders of this culture obsessed between the difference between true south-southeast and nearly south-southeast, but once they got to the promised land, they stopped caring about precision and decided to call west north?”

First, I’d have a hard time labelling a single reference “obsessed”. Second, they don’t seem to have used the Liahona for that purpose once they got to the New World, which would make sense if it was an astrolabe, plotted to the star patterns of the Middle East. So no, I don’t find it odd that some precision might’ve been lost as a result. And as for Sorenson, there’s a great deal of good thinking on that subject that you seem to be gliding past:

https://www.fairlatterdaysaints.org/conference/august-2012/from-the-east-to-the-west-the-problem-of-directions-in-the-book-of-mormon

Thanks Billy! Last word is yours if you want it.

“The Bible gives 465 cardinal directions, and no intercardinal directions. The BofM also gives many, many such cardinal directions, and only one intercardinal direction. If it instead had a few dozen such references you might be on to something. But as it stands, plugging those values into a chi-square doesn’t give us much to hold onto from a statistical standpoint.”

You misunderstand my argument. It isn’t just that the Book of Mormon happens to contain an anachronistic, overly-specific, intercardinal direction. It’s the specific context. The author needed to find a plausible path to get his characters from a known location, Jerusalem, to the open ocean. To do this, a modern author would be expected to consult a map. The anomaly happening in the one place where a modern author would need to look at a map is a smoking gun.

One more related point on directions. John Sorenson rotates the map 90 degrees to make his geography work (e.g. the east sea is really to the north, the west sea is really to the south, the land north of the narrow neck of land is really the land west of the narrow neck of land, etc.). Do you find odd that the founders of this culture obsessed between the difference between true south-southeast and nearly south-southeast, but once they got to the promised land, they stopped caring about precision and decided to call west north?

I recall talking to a well-credentialed non-Mormon scholar who happened to be very familiar with Mormon apologetics. He told me he thought Nahom was the most important piece of evidence in favor of the Book of Mormon. Given that, I was surprised that its evidence score is only a 2.

A couple of points come to mind.

First, arguments that it is unlikely Joseph Smith wrote the book are NOT arguments that the book is authentic. Arguing Joseph Smith was too untalented to write an 800 page book could be arguing that somebody else wrote it. Arguing he was too untalented could even be arguing he had supernatural help. But supernatural forces could help somebody write fiction just as much as they could help somebody write authentic history. Who wrote the book and how is an interesting issue. Whether it is ancient is different issue.

When I open up the Book of Mormon to 1 Nephi 16 and consider their trek towards the sea, on the one hand I’m impressed with how well the route fits with what we see on a modern map, and I’m impressed with the hit Nahom. But on the other hand I’m blown away by a glaring anachronism. “And it came to pass that we traveled for the space of four days, nearly a south-southeast direction.” (1 Nephi 16:13). In 600 B.C., nobody referred to a direction with a term meaning “nearly south-southeast.” People talked of north, east, south and west. They talked about up towards the mountains or down towards the water. But they didn’t say “nearly south-southeast.”

The fact that it uses this anachronistic language is strong evidence that it is of modern origin. Given that the Arabian peninsula is oriented in a south-southeast direction, it would seem likely that the author was in fact using a map to get a plausible route for their fictional characters to travel from a historical location to the sea.

The anachronism “nearly south-southeast” cancels out the positive evidence Nahom, and I’m left with my original odds.

“He told me he thought Nahom was the most important piece of evidence in favor of the Book of Mormon.”

There’s a difference, I think, between “important”, and “unexpected”. I’d agree that Nahom is pretty up there in terms of importance, since the archaeological aspects of it have a lot of consensus, and it serves as a concrete linchpin for the rest of the Old World evidence. But my analysis suggests that chance would have a decent (though still unlikely) shot at producing the evidence we have, reducing its “unexpectedness”, and thus it’s Bayesian impact.

“First, arguments that it is unlikely Joseph Smith wrote the book are NOT arguments that the book is authentic.”

f the evidence is expected under the hypothesis of authenticity, then functionally that’s exactly what those arguments are. In this kind of analysis, the only way to improve the likelihood of a hypothesis is to demonstrate that competing hypotheses are less likely. As with your “satanic” hypothesis from a couple posts ago, we could definitely put up an “inspired fiction” hypothesis and see how it fares against the others, it seems to me that God would’ve been putting in an awful lot of work just to give us a work of fiction (and such a hypothesis would still leave us with an authentic deity, so, score one for theists). In any case, a narrative detail that ties the book so closely to the world as it would’ve been lived by Lehi has to be seen as a tally in the “authentic” column.

“People talked of north, east, south and west.”

This is a thought that I hadn’t come across before. The faithful scholars that I can find tend to find this detail interesting (usually in contrast to the reliance on cardinal directions that pervades the rest of the book), but none suggest it’s a problem that needs resolving (and they’re usually good at picking up on those things). I also can’t seem to find a critical source for it.

Taking a look, though, seems like the concept of intercardinal directions was far from foreign in the ancient world. The Romans, for instance, had ways of expressing a variety of them, though they had separate terms for each, and you can see similar things in many other ancient cultures.

https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-Latin-words-for-intercardinal-intermediate-directions-and-their-forms-as-an-adjective-like-southeastern

Since a modern (or early modern) English audience would’ve only had our compass system to work with, it’s not surprising for 1 Nephi 16:13 to have been rendered the way it is.

Most commenters find it telling that Nephi uses this term right after they come across the Liahona. If the Liahona was a kind of primitive astrolabe, as suggested by Gervais and Joyce in the Interpreter, it could have allowed Nephi to get rather precise in how he described direction, to the point that the best an English translation could do might be “nearly south-southeast”. Here’s the Interpreter article, for reference:

https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-small-means-rethinking-the-liahona

“I’m impressed with how well the route fits with what we see on a modern map, and I’m impressed with the hit Nahom.”

On that we’re definitely agreed, though I find it telling that you have to keep borrowing from other supposed anachronisms to stop that impression from sticking around. Can’t have that, now can we!

“If the evidence is expected under the hypothesis of authenticity, then functionally that’s exactly what those arguments are. In this kind of analysis, the only way to improve the likelihood of a hypothesis is to demonstrate that competing hypotheses are less likely.”

I agree with this in principle. However, evidence of the book being ancient are in fact categorically different than evidence that Joseph Smith couldn’t have written it. There is a reason nobody has submitted to the Journal of Archeological Research a paper that said the Book of Mormon should be placed ahead of Popol Vuh as the most important ancient Mesoamerican book because eleven witnesses claimed they saw some gold plates before they were taken away by an angel and because the Book of Mormon is 800 pages long, was written in 45 days, AND contains the word Nahom.

The book being ancient and how it was produced are two different issues.

This reminds me of the Cottingley fairies. About a hundred years ago, some young girls in the English town of Cottingley took some photographs of fairies in their garden. Experts examined the photographs and decided that they were entirely genuine, not the least bit fake. Nobody could imagine how these young girls could have possibly created such masterful forgeries, and some concluded it was proof that fairies were real.

Was the fact nobody could come up with a plausible way the girls could have mustered the resources to create such convincing forgeries evidence that fairies are real?

Perhaps. But after more than 60 years one of the girls, now an old lady, confessed. They had cut pictures out of books, drawn wings on them, propped up the pictures with hat pins, and snapped the photographs. It turned out to have been quite easy for them.

“I find it telling that you have to keep borrowing from other supposed anachronisms to stop that impression from sticking around. Can’t have that, now can we!”

I’m at an insurmountable disadvantage here because I don’t know what evidence you are going to introduce in future episodes. For this exercise to be valid it needs to contain all the evidence, not just the pieces you carefully curate to arrive at the conclusion you want to.

“This reminds me of the Cottingley fairies.”

In that case, a single image doesn’t give people a whole lot to hold on to in terms of disconfirming competing explanations. The BofM should be a much different case, with hundreds of pages of text and dozens of years of history associated with its coming forth, not to mention hordes of critics gleefully pouring thousands of man hours trying to tear it down. That viable competing explanations have proven so elusive should give the esteemed editors of the Journal of Archaeological Research some pause. It certainly gave Sorenson pause–enough that he was able to see a great deal that no traditional archaeologist would have been willing to contemplate otherwise. The evidence we’ve considered so far wouldn’t be enough to bust down the doors of the Smithsonian (as my current posterior would suggest), but perhaps it would be enough to crack a window.

In terms of your reply to Bruce, though, that article gives a solid accounting of how direction got started, and would explain why most (though not all) directional systems are cardinally-based. But you’ll notice that there’s nothing in there that approaches the type of claim you’re trying to make–that the ancients never thought or spoke in terms of intercardinal directions. That’s because such a claim is clearly not accurate, with a myriad of ancient examples that contradict it.

The Bible gives 465 cardinal directions, and no intercardinal directions. The BofM also gives many, many such cardinal directions, and only one intercardinal direction. If it instead had a few dozen such references you might be on to something. But as it stands, plugging those values into a chi-square doesn’t give us much to hold onto from a statistical standpoint.

For it to effectively counter Nahom, you’d need to demonstrate that we’d need to find at least a hundred ancient books like the Book of Mormon (with a similar amount of directional references) before we’d expect to find even a single intercardinal reference. I’m afraid nothing you’ve presented here would suggest that’s the case, particularly not in the context of the other material I’ve encountered on the subject.

Billy,

What evidence can you offer that ancient people limited themselves to only the four cardinal directions (north, east, south, west), as you claim? I know of no such evidence, but perhaps you do? Please provide some support for your claim.

Bruce

Hi Bruce,

Please read Cecil Brown’s paper, “Where do Cardinal Direction Terms Com From?” in the journal Anthropological Linguistics, January 1983. The way virtually all languages develop four terms for the same four cardinal directions indicates that people naturally see the world this way.

As an example of how the human brain works, imagine you were on the freeway with somebody who wasn’t familiar with the map of Michigan and started driving towards Grand Rapids. If you asked him what direction you were going based only on his own senses and the sun and stars, in all likelihood he would say “We are going west.” He wouldn’t say, “we are headed in a nearly west-northwest direction.”

As another example, the Bible refers to directions 465 times. Without exception, every direction it references is one of the four cardinal directions. Not once does it list any of the other four directions on the eight-point compass rose (e.g. northwest), much less one on the other twelve directions on the sixteen-point compass rose (e.g. south-southeast).

Best,

Billy

Billy,

With apologies to Inigo Montoya, I don’t think that article says what you think it says.

As the article’s author Cecil Brown states on page 125, it seems true that “… there is little reason to believe that cardinal directionality would have been of any great use to peoples of small scale societies of the past.”

Why have a word for something that is not important to you?

However, I read the article all the way through. Nowhere does it state that ancient societies never thought in terms of intercardinal directions. You are simply wrong on that point, Billy.

Quite the opposite, in fact. I counted a total of 20 separate times in this article in which the author references words for intercardinal directions in the speech of ancient peoples (see pgs. 132 and 139-141).

For example, the ancient Polynesian seafarers, for whom a word for the precise direction from which the wind was blowing was very important, did have such precise words. (You aren’t going to get where you want to go in your inter-island voyages unless you are very clear about the direction from which the wind is blowing.)

One Polynesian group used a word meaning “east-south-east trade wind” (pg. 140-141). They needed to be precise about the direction of the wind, and so they were. Likewise Lehi’s party had to travel in a very specific direction (nearly south-southeast) if they were to arrive at a fairly small fertile region, called Bountiful, on the eastern coast of the Arabian peninsula.

So, Billy, using an intercardinal direction is not an anachronism in the Book of Mormon, as you claim. Ancient societies did use intercardinal directions, another point for the Book of Mormon. Will you gracefully acknowledge your mistake or not?

I can hope, but I am not holding my breath.

Bruce

Here is the link to the article by Cecil Brown.

https://www-jstor-org.proxy2.cl.msu.edu/stable/30027665?pq-origsite=summon&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

ps. This is probably my last comment on this episode…I will be fishing in Alaska next week. Wish me luck!

Inconceivable!

You are right Bruce—some ancient people in some contexts did use directions other than the four cardinal directions. Thank you for correcting me.

But saying this is “another point for the Book of Mormon” is Daleish thing to say. In context, the way Nephi says “nearly south-southeast” is still an anachronism. We know some ancient sailors referred to other directions based on wind. Sure. But Nephi wasn’t sailing when he talked of this oddly-specific direction. And how would a nautical term for “nearly south-southeast” even be in his vocabulary?

In any case, enjoy your fishing trip.

Sorry, Billy, but I’m not buying your explanation. Not at all.

You submitted the article by Brown to this discussion as proving your point that the ancients didn’t think in terms of intercardinal directions. Since the article says nothing of the kind, but rather supports exactly the opposite conclusion, I can think of only three possible reasons why you would do this.

You referenced the article either because:

1) you didn’t read it, but thought you could bluff your way through our discussion of this point by citing an obscure article that I either wouldn’t be able to find or wouldn’t take the time to read, or,

2) you did read it, but not carefully, and missed the 20 references to intercardinal directions in the article, or,

3) you did read it, saw the references to intercardinal directions, but decided to ignore them in an effort to win your point.

None of these explanations reflects well on you, Billy. Can you offer a more benign explanation? I do like to think well of people, especially people with whom I disagree.

You are making that difficult for me.

As you know, you and I have interacted a lot, beginning with your responses to the article my son and I wrote a couple of years ago entitled “Joseph Smith: The World’s Greatest Guesser…” Spoiler alert: my son and I have a second, related article on the way citing even more “Daleish” points supporting the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. (Thank you for the compliment about being “Daleish”, guilty as charged, yer honor!)

I am finding the same pattern of behavior in your discussion of Kyler’s posts that I found when we interacted about our first article. When confronted with strong evidence in support of the Book of Mormon or the prophetic credentials of Joseph Smith, you really don’t engage with the evidence, but always seek to change the subject.

You have done that again here.

Since the article you cited does not support your point, but instead supports exactly the opposite conclusion, you changed the subject. Now the subject is that navigating the ocean is not the same thing as navigating the desert.

Jeepers, Billy! Can’t you do better than that?! The current subject (raised by you and not really related to the subject of Nahom, Kyler’s most recent post) is that the ancients didn’t think in terms of intercardinal directions. Well, they did. So now you want to change the subject, again.

OK, I will bite on the new subject and then I am going to bite back.

The navigation problem is very much the same. You have a vast desert to traverse with few landmarks, and you need to head in very specific direction(s) if you are to survive and succeed in your journey. (Are you aware of the many poems and metaphors that compare the desert to the ocean? Check it out. Those poems and metaphors exist for good reasons.)

A cardinal direction (east or south) will not do—you have to be more specific, a lot more specific. And so the Liahona did guide Lehi’s party in specific directions, a fact that Nephi remembered and recorded.

Now I get to bite back. As long as we are in the desert, and changing the subject, let me direct your attention to another authentic, desert-related detail in the Book of Mormon. In 1 Nephi 2:6, Lehi’s party arrives at “a river of water”. Well, what other kind of river is there other than a river of water, Nephi? Talk about a dumb statement.

Except it is not dumb to someone who grew up in the Arizona desert, as I did. In the desert you have two kinds of rivers, the very infrequent river of water, and the much more common river of sand, the dry wash that carries water only seasonally. You even have different words to describe them, the same distinction Nephi makes. In Arizona we used the Spanish word for these dry washes, “arroyos”.

Right on, Nephi! Bullseye, bro! A strong point for the defense, “Daleish” or otherwise.

OK, now I am going fishing. Thanks for the well-wishes on my fishing adventure, Billy. I am done commenting on this post by Kyler. But I am confident that you will change the subject…again.

I was thinking on your calculus. Two scenarios: A) There is map that you cannot see with several names, some with 1 consonant, 2 consonants, …, 6 consonants Names. What is the chance to write down a name that match one the names of the Map? => This would be your calculus, you could chose 1 consonant name; 2 consonants names (18,67% chance); 3 consonants names (48,67% chance), and so on… B) The same map that you cannot sse, you chose a 3 consonant Name, what is the chance to match one of Names of the Map? => As Joseph already picked out a name, the chances would be p = (1/22)^3*48 (48 different three consonants Names in the Map) => 4,5*10^-3 => 4 to 5 chance in 1000. You calculated the chance for Scenario A, I think that the correct should be the calculus for Scenario B.

Thanks for reading these so closely Marcelo. I’m happy to have had these typos caught.

Your alternate way of framing the problem is an interesting one, for sure. What your two scenarios represent are essentially: A) what is the probability that Joseph could’ve picked a name that would later match a location in that region, and B) what is the probability that faithful scholars would be able to make a (spurious) connection to the name chosen by Joseph.

Given how our Bayesian analysis is framed, I think you could make an argument for either one (i.e., we’re trying to figure out the probability of “observing the evidence” under given hypotheses, and each would be a way to produce the evidence we see). But I think ultimately Scenario A is a better fit for what we’re going for. The focus here is on Joseph’s processes, not ours, and Scenario A captures the partially randomized process he would’ve had to use to generate names. And if Joseph’s name generation process could’ve created the connection more easily than it would’ve been for us to make a connection to the name he chose, I think it’s appropriate for the former to take precedence. And since doing so happens to favor the critics, it would be yet another way to exercise a fortiori reasoning.

Cheers!

Ok Kyler!

I was thinking even better and noticed that in both scenarios A) and B) above, we are not calculating the probability to get right a 3 consonant Noum (which is always (1/22)^3) ~ 0.94*10^-4), but the expected frequency to find “NHM” in a map. Notice that if my Map had 10,000 different toponyms with 3 consonants, it would cover almost all variants and we would expect to find at least 1 toponym called “NHM”. If we had 20,000 toponyms, 2 “NHM”s and so forth. This last one could not be understood that the probability is 200%, but to expect find 2 “NHM”s in the midle of 20,000 randomic names of three consonants. In your case, Scenario A) frequency is 0,97%, find one match in a Map, i.e., if we had 100 Maps similar to Arabian Peninsula area, we would expect find one that matches with a Book of Mormon Name (we could expand this analysis to verify that Moroni & Cumores is not so impressive).

“So that 4 in 10,000 chance is pretty low” => With the correction above should be 4 in 100,000, even lower…

The table values are correct: 2 Letters => 3,85*10^-4 ; 3 Consonants => 4,38*10^-5 … etc. But I don’t agree that you should add all % from all letters. Joseph Smith already choosed a 3 consonants “Name”. You should look only to the number of three consonants Name places on the Map, i.e., 48 in the shadow area. Thus, p = 48*4,38*10^-5 = 2,1*10^-3 => Two chances in 1000 or 1 chance in 500.

You could figure out the extreme scenario: If Joseph Smith had chosen the only 6 consonants word that match in the map (Kasr El-Nad) and hit it on => His accomplishment would be more impressive: 1,2*10^-10 => 1 chance in 10,000,000,000. But, if you sum all numbers of your table, you’d get 0,009 again !

“select from the 22 consonants in the Hebrew language to try and guess each of those three. That probability all by itself is easy enough to calculate at p = .0009.”

My calculus shows a one more zero after the decimal : p = 1/22*1/22*1/22 = 0.0000939