This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Figure 1. Thomas Cole, 1801-1848: The Subsiding Waters of the Deluge, 1829.

Thomas Cole’s artistry evokes poignant emotions as it leads the viewer’s eye from the foreground to the background of the painting. The rough rocks nearby recall recent scenes of cleansing upheaval and destruction; beyond them, the Ark is finally at rest in calm waters, a witness of the divine love that preserved its righteous passengers in their journey through the deep; in the distance, the towering peak is a beacon of hope, a “Sinai” for Noah — presaging new revelation for the faithful remnants of humanity.

Though the Book of Moses ends abruptly with the Lord’s declaration of the Flood in Moses 8:30, we continue the story of Noah, the Ark, and the Flood in the Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis 6–8 within this essay.

In the Bible, Noah’s ark is described as a huge, rectangular box with three floors and a roof, which makes it sound more like a building than a boat. Was Noah’s ark designed as a floating “temple”? Before addressing this question, it will be important to remind ourselves about how people in ancient times read scripture.

How Did People in Ancient Times Read Scripture?

The Prophet Joseph Smith held the view that scripture should be “understood precisely as it reads.”[1] In saying this, however, it must be realized that what ancient peoples understood to be a literal interpretation of scripture is not the same as what most people think of today.

To those who recorded Bible history, it was not enough to describe events in photojournalistic fidelity to the sights and sounds that might have been picked up “objectively” by a camera (if one had been available in their day). Rather, an inspired author would want to write a history that acknowledged the hand of God within every important occurrence. To the ancients, important events in history were part of “one eternal round.”[2] They took pains to help the reader detect that current happenings were consistent with divine patterns seen repeatedly within scriptural “types” at other times in history —past and future. A simple description of the bare “facts” of the situation, as we are culturally conditioned to prefer today, would not do for our forebears.[3]

Consider, as a more recent example, Joseph Smith’s description of the Book of Mormon translation process. Modern readers are usually interested in the detailed, “literal” accounts given by some of the Prophet’s contemporaries about the size and appearance of the instruments he was supposed to have used and the exact procedure by which the words of the ancient text were made known to him. This kind of account appeals to us — the more physical details the better — because we think this kind of history will help us best understand what “actually happened” as Joseph Smith translated.

However, we should realize that Joseph Smith himself declined to relate the specifics about how he translated, even in response to direct questioning while he was meeting with a small group of believing friends.[4] The only explicit statement he made about the translation process is his testimony that it was accomplished “by the gift and power of God,”[5] a description that avoids reinforcing the misleading impression that we can understand “what really happened” through detailed accounts of observers.

Of course, there is no reason to throw doubt on the idea that instruments and procedures such as those described by Joseph Smith’s contemporaries were used in translation. However, by wisely restricting his description to the statement that the translation was accomplished “by the gift and power of God,” the Prophet resisted the effort to describe this sacred process in a way that would appeal to modern standards and sensibilities. Instead, he pointed attention to what mattered most: that the translation was accomplished by divine means.

How should this lesson be applied to the story of Noah? As we will see, the story provides plenty of physical details, such as the size of the Ark, the place where it landed, and the date of its debarkation. All these details are important to the story — indeed they are crucial to our understanding. However, in most cases, you can be sure that small details of this sort are not included merely to add a touch of “realism” to the account for the sake of moderns such as you and me. Rather, they are there to help readers make mental associations with scriptural stories and religious concepts found as “types” elsewhere in scripture. In the case of Noah, for example, those who wrote the Bible seem to have wanted to highlight themes that would tie back to the story of Creation and would anticipate the Tabernacle of Moses. A photorealistic description of the Flood would not have accomplished the aims of its author. What readers needed most was not a modern historical account, but rather some help to recognize the backward and forward reverberations of Noah’s story elsewhere in scripture.

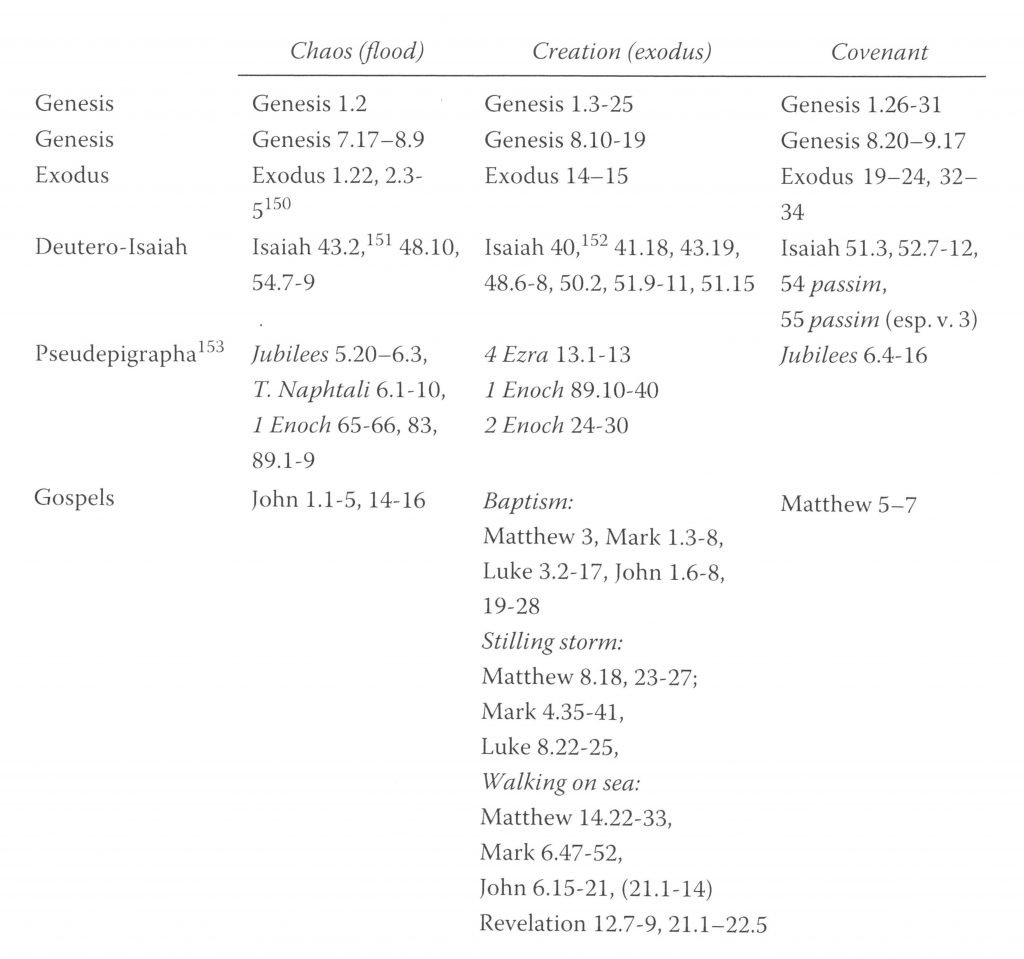

Figure 2. Typology in the Biblical Tradition

That the story of Noah repeats, with some variation, the themes of the Creation, the Garden of Eden, the Fall of Adam and Eve, and the Atonement by which the covenant is renewed has long been recognized by Bible scholars (see, e.g., Figure 2). What deserves greater appreciation, however, is the nature and depth of the relationship between these accounts and the liturgy[7] and layout of temples, not only in Israel but also throughout the ancient Near East. Whether we understand “Noah’s ark as a Primeval tabernacle or the tabernacle as Israel’s ‘ark,’” we concur with Triolo that the evidence is compelling in “reading both structures in relation to each other.”[8]

With these considerations in mind, let’s consider how we might be able to see Noah’s ark as a deliberately designed floating temple.

Figure 3. Noah Sees the Ark in Vision. Detail of Patriarchs Window, Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, England.

Resemblances Between the Ark and the Tabernacle

It is significant that, apart from the Tabernacle of Moses[10] and the Temple of Solomon,[11] Noah’s ark is the only man-made structure mentioned in the Bible whose design was directly revealed by God.[12]

In this image, God shows the plans for the Ark to Noah just as He later revealed the plans for the Tabernacle to Moses. The hands of Deity hold the heavenly curtain as Noah, compass in his left hand, regards intently.

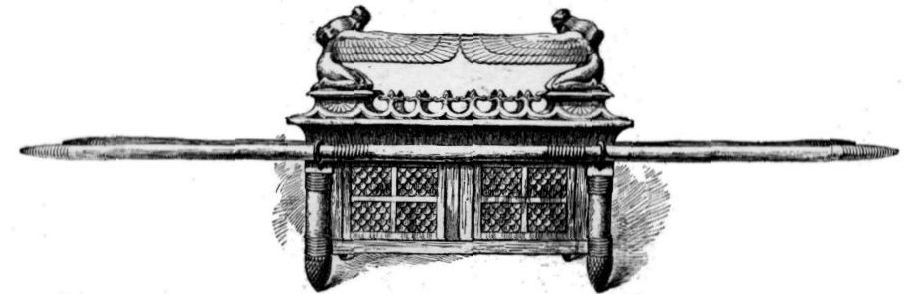

Figure 4. J. James Tissot, 1836-1902: The Ark of the Covenant, ca. 1896-1902.

Layout and size of the Ark. There is a growing consensus among Bible scholars that, like the Tabernacle, Noah’s Ark “was designed as a temple.”[14] The Ark’s three decks suggest both the three divisions of the Tabernacle and the threefold layout of the Garden of Eden.[15] Indeed, each of the three decks of Noah’s Ark was exactly “the same height as the Tabernacle and three times the area of the Tabernacle court.”[16] Strengthening the association between the Ark and the Tabernacle is the fact that the Hebrew term for Noah’s Ark, tevah, later became the standard word for the Ark of the Covenant in Mishnaic Hebrew.[17] In addition, the Septuagint used the same Greek term, kibotos, for both Noah’s ark and the Ark of the Covenant.[18] Signaling another resemblance is that the ratio of the width to the height of both of these arks is 3:5.[19]

Figure 5. Rectangular Ark from Aronofsky’s Noah film, 2015. In contrast to many other aspects of the film, the shape of the Ark was in line with modern scholarship.

Rectangular shape and free-floating nature of the Ark. Going further, the shape of Noah’s ark was very un-boat-like. Westermann describes it as “a huge, rectangular box, with a roof.”[20] Thus, like the Ark of the Covenant, it was shaped like a chest. Not only was the Ark “not shaped like a ship,” it also lacked oars, “accentuating the fact that Noah’s deliverance was not dependent on navigating skills, [but rather happened] entirely by God’s will.”[21] Its movement was solely determined by “the thrust of the water and wind.”[22] This reminds us of the story of the infant Moses, the only other place in the Bible where the Hebrew word for ark appears. As you recall Moses’ deliverance from death was also made possible by a free-floating watercraft — specifically, in this case, a reed basket.[23] Reeds also seem to have been used as part of the construction materials for Noah’s Ark, as we will now discuss.

Temple allusions in the materials used to build the Ark. Genesis 6:14 reads: “Make thee an ark of gopher wood; rooms shalt thou make in the ark, and shalt pitch it within and without with pitch.” Each of these three types of materials seem to have had temple connotations:

- Gopher wood. The referent for the term “gopher wood” — unique in the Bible to Genesis 6:14 — is uncertain.[24] Modern commentators often take it to mean cypress wood.[25] Because it is resistant to rot, the cypress tree was used in ancient times for the building of ships.[26] There is an extensive mythology about the cypress tree in cultures throughout the world. It is known for its fragrance and longevity[27] — qualities that have naturally linked it with ancient literature describing the Garden of Eden.[28] Cypress trees were sometimes used to make temple doors — gateways to Paradise.[29]

- Pitch. There is a possibility of wordplay in the rhyme between gopher and kopher (“pitch”) within the same verse. As Harper notes, the word kopher might have reminded the ancient reader of “the rich cultic overtones of kaphar ‘ransom’ with its half-shekel temple atonement price,[30] kapporeth ‘mercy seat’ over the Ark of the Covenant,[31] and the verb kipper ‘to atone’ associated with so many priestly rituals.”[32] Some of these rituals involve the action of smearing or wiping, the same movements by which pitch is applied.[33] Just as God’s presence in the Tabernacle preserves the life of His people, so Noah’s Ark preserves a righteous remnant of humanity along with representatives of all its creatures.

Figure 6. Nik Wheeler, 1939-: Marsh Arab Village, 1974.

- Reeds. Although reed-huts may sometimes serve as secular enclosures, references to them in Mesopotamian flood stories clearly point to their ancient use as divine sanctuaries.[34] In a Mesopotamian account of the flood story, Ziusudra enters into a “reed-hut… temple,”[35] where he stands “day after day” listening to the “conversation” of the divine assembly.[36] Eventually, Ziusudra learns that the council of the gods have decided to destroy mankind by a devastating flood. Regretting the decision, the god Enki warns Ziusudra and instructs him on how to build a boat. Similar to ancient Near East parallels where the gods whisper their secrets to mortals standing on the other side of temple veils separating the divine and human realms,[37] Enki conveys his message privately through a thin wall of the sanctuary.[38] Related accounts tell us that Enki instructed Ziusudra to tear down the reed-hut temple and to use the materials to build a boat.[39]

Concluding “that the apparent lack of the reed-hut or primeval shrine in the Genesis flood account demands closer inspection,”[40] Jason McCann observes[41] that reinterpreting the Hebrew for the description of “rooms” in the Ark would lead to an alternate translation describing it aswoven-of-reeds.”Thus, the and caulk it with pitch inside and out.”

- Window. The meaning of the obscure term tsohar is debated, but throughout Jewish midrash it is understood, not as a window but rather as a reference to a shining stone that was said to have hung from the rafters of the ark in order to lighten the darkness within.[43] Readers of the Book of Mormon will not miss the similarity to the story of the shining stones divinely provided to the brother of Jared to provide light for their barges (Ether 3:1-6, 6:3). Similarly, the Vara of the Avestan “flood” hero Yima contained “a variety of sources of artificial light which make a year seem like a day.”[44] More importantly, these were sources of spiritual light, as is discussed in Essay #77.

Let’s now turn our attention to Creation and Garden themes in the story of the Flood, where we will find temple parallels not only to the structure of the Ark, but also in its function.

Creation. In considering the role of Noah’s ark in the flood story, it should be remembered that it was, specifically, a mobile sanctuary,[45] as were, of course, the Israelite Tabernacle and the ark made of reeds that saved the baby Moses.

Despite its ungainly shape as a buoyant temple, the Ark is portrayed as floating confidently above the chaos of the great deep. Significantly, the motion of the Ark “upon the face of the waters”[46] paralleled the movement of the Spirit of God “upon the face of the waters”[47] at the original creation of heaven and earth. The deliberate nature of this parallel is made clear when we consider that these are the only two verses in the Bible that contain the phrase “the face of the waters.” In short, we are made to understand that in the presence of the Ark there has been a return of the same Spirit of God that had hovered over the waters at Creation — the Spirit whose previous withdrawal had been predicted in Genesis 6:3.[48]

Figure 7. The Ark as a Mini-Replica of Creation.

The motion of the Ark “upon the face of the waters,”[49] like the Spirit of God “upon the face of the waters”[50] at Creation, was a portent of the appearance of light and life. Within the Ark, a “mini replica of Creation,”[51] were the last vestiges of the original Creation, “an alternative earth for all living creatures,”[52] “a colony of heaven”[53] containing seedlings for the planting of a second Garden of Eden,[54] the nucleus of a new world — all hidden within a vessel of rescue described in scripture, like the Tabernacle, as a likeness of God’s own traveling pavilion.[55]

Just as the Spirit of God patiently brooded[56] over the great deep at Creation, and just as “the longsuffering of God waited … while the ark was a preparing,”[57] so the undauntable Noah endured the long brooding of the Ark over the slowly receding waters of the Deluge.[58] At last, the dry land appeared.[59]

The settling of the Ark at the top of the first mountain to emerge after the Flood would have reminded ancient readers of the emergence of the dry land at Creation. In ancient Israel, the Foundation Stone in front of the Ark of the Covenant:[60] “was the first solid material to emerge from the waters of Creation,[61] and it was upon this stone that the Deity effected Creation.”

Note also that it was “in the six hundred and first year [of Noah’s life] in the first month, the first day of the month” that “the waters were dried up.”[62] The wording of this verse would have hinted to ancient reader that there was special significance to the date. They would have remembered that it was also the “first day of the first month”[63] when the Tabernacle was dedicated, and that “Solomon’s temple was dedicated at the New Year festival in the autumn.”[64]

Figure 8. J. James Tissot, 1836-1902 : Noah’s Sacrifice, ca. 1896-1902.

Garden. Allusions to Garden of Eden and temple themes begin as soon as Noah and his family leave the Ark. Just as the Book of Moses highlights Adam’s diligence in offering sacrifice as soon as he entered the fallen world,[65] Genesis describes Noah’s first action on the renewed earth as being the building of an altar for burnt offerings.[66] Likewise, in both accounts, God’s blessing is followed by a commandment to multiply and replenish the earth.[67] Both stories contain instructions about what the protagonists can and cannot eat.[68] Notably, in each case, a covenant is established in a context of ordinances and signs or tokens.[69] More specifically, according to Pseudo-Philo,[70] the rainbow as a sign or token of a covenant of higher priesthood blessings was said by God to be as an analogue of Moses’ staff, a symbol of kingship.[71] Both the story of Adam and Eve and the story of Noah prominently feature the theme of nakedness being covered by a garment.[72] Noah, like Adam, is called the “lord of the whole earth.”[73] Surely, it is no exaggeration to say that Noah is portrayed as a new Adam, “reversing the estrangement” between God and man by means of an atoning sacrifice.[74] Having outlined some of the Creation and Garden themes within the story of Noah, the next essay will discuss a “fall” and consequent judgment.

This article is adapted from J. M. Bradshaw, et al., God’s Image 2, pp. 199-294. See also this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kIfArfB54Mk. For additional material on temple symbolism in the story of Noah, see J. M. Bradshaw, Ark and Tent.

For a review of Aronofsky’s fascinating but ultimately disappointing 2014 film version of the story of Noah, see J. M. Bradshaw, Noah Like No Other.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cole_Thomas_The_Subsiding_of_the_Waters_of_the_Deluge_1829.jpg (accessed September 20, 2013).

Figure 2. The table is based on the work of A. J. Wensinck, and is adapted with the permission of Nicolas Wyatt. Original in Nicolas Wyatt. “‘Water, water everywhere…’: Musings on the aqueous myths of the Near East.” In The Mythic Mind: Essays on Cosmology and Religion in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicholas Wyatt, 189-237. London, England: Equinox, 2005, pp. 224-225.

Figure 3. Stephen T. Whitlock, 1951-; Photograph IMGP1821, 24 April 2009, © Stephen T. Whitlock. Detail of Patriarchs Window, Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, England.

Figure 4. Image from Tissot, J. James. The Old Testament: Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, Parts 1 and 2. 2 vols. Paris, France: M. de Brunhoff, 1904, 1:229.

Figure 5, https://www.deseret.com/2014/4/3/20538777/a-noah-like-no-other-before-a-look-at-the-latest-biblical-film-from-an-lds-perspective#the-ark-in-noah-from-paramount-pictures-and-regency-enterprises (accessed September 4, 2021). For a review of the film from the perspective of the Bible and scholarship, see J. M. Bradshaw, Noah Like No Other.

Figure 6. Corbis Images, image reference: NW004595.

Figure 7. Fotolia, image reference: 9267857 – apocalypse.

Figure 8. The Jewish Museum, New York/Art Resource, NY, image reference: ART45833, with the assistance of Liz Kurtulik and Michael Slade.

References

Abarqu’s cypress tree: After 4000 years still gracefully standing. 2008. In CAIS News, The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies. http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2008/April2008/25-04.htm. (accessed August 1, 2012).

Alter, Robert, ed. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2004.

———, ed. The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2007.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Augustine. d. 430. St. Augustine: The Literal Meaning of Genesis. New ed. Ancient Christian Writers 41 and 42. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1982.

Barker, Kenneth L., ed. Zondervan NIV Study Bible Fully Revised ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

Barker, Margaret. "Atonement: The rite of healing." Scottish Journal of Theology 49, no. 1 (1996): 1-20. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/scottish-journal-of-theology/article/abs/atonement-the-rite-of-healing/ECB25D3391C9D1026FD6E00C5EB36270. (accessed August 3).

———. E-mail message to Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, June 11, 2007.

———. The Hidden Tradition of the Kingdom of God. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 2007.

Black, Jeremy A., G. Cunningham, E. Robson, and G. Zolyomi. "Enki’s journey to Nibru." In The Literature of Ancient Sumer, edited by Jeremy A. Black, G. Cunningham, E. Robson and G. Zolyomi, 330-33. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010.

———. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010. www.templethemes.net.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. "The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol4/iss1/1/.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary." In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013. https://rsc.byu.edu/ascending-mountain-lord/tree-knowledge-veil-sanctuary ; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfIs9YKYrZE. (accessed June 21, 2021).

———. "The ark and the tent: Temple symbolism in the story of Noah." In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 25-66. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-ark-and-the-tent-temple-symbolism-in-the-story-of-noah/. (accessed August 21, 2021).

———. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. "A Noah like no other before: A look at the latest biblical film from an LDS perspective." Deseret News, 3 April 2014, 2014. https://www.deseret.com/2014/4/3/20538777/a-noah-like-no-other-before-a-look-at-the-latest-biblical-film-from-an-lds-perspective#the-ark-in-noah-from-paramount-pictures-and-regency-enterprises. (accessed September 4, 2021).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and David J. Larsen. Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel. In God’s Image and Likeness 2. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/131203ImageAndLikeness2ReadingS.

Brown, Francis, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs. 1906. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005.

Budge, E. A. Wallis, ed. The Book of the Cave of Treasures. London, England: The Religious Tract Society, 1927. Reprint, New York City, NY: Cosimo Classics, 2005.

Butterworth, Edric Allen Schofeld. The Tree at the Navel of the Earth. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter, 1970.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 1: From Adam to Noah. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1998.

———. 1949. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 2: From Noah to Abraham. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1997.

. Paris, France: Desclée de Brouwer, 2003.

Clifford, Richard J. The Cosmic Mountain in Canaan and the Old Testament. Harvard Semitic Monographs 4, ed. Frank Moore Cross, William L. Moran, Isadore Twersky and G. Ernest Wright. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, n.d.

———. "The temple and the holy mountain." In The Temple in Antiquity, edited by Truman G. Madsen, 107-24. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1984.

Cohen, Chayim. "Hebrew tbh: Proposed etymologies." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 4 (1972): 37-51. http://www.jtsa.edu/Documents/pagedocs/JANES/1972%204/CCohen4.pdf. (accessed May 20, 2012).

Dalley, Stephanie. "Atrahasis." In Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, edited by Stephanie Dalley. Oxford World’s Classics, 1-38. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2000.

De Vaux, Roland, ed. Nouvelle ed. Paris, France: Desclée de Brouwer, 1975.

Le Pentateuque d’Alexandrie: Texte Grec et Traduction. ed. Cécile Dogniez and Marguerite Harl. Paris, France: Les Éditions du Cerf, 2001.

Douglas, Mary. "Atonement in Leviticus." Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 2 (1993-1994): 109-30.

———. Leviticus as Literature. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Drower, E. S., ed. The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1959. http://www.gnosis.org/library/ginzarba.htm. (accessed September 11, 2007).

Dunn, James D. G., and John W. Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Eden, Giulio Busi. "The mystical architecture of Eden in the Jewish tradition." In The Earthly Paradise: The Garden of Eden from Antiquity to Modernity, edited by F. Regina Psaki and Charles Hindley. International Studies in Formative Christianity and Judaism, 15-22. Binghamton, NY: Academic Studies in the History of Judaism, Global Publications, State University of New York at Binghamton, 2002.

Ephrem the Syrian. ca. 350-363. Hymns on Paradise. Translated by Sebastian Brock. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1990.

Epstein, Isodore, ed. The Soncino Hebrew-English Talmud (Babylonian). 30 vols. London, England: The Soncino Press, 1948. http://www.come-and-hear.com/tcontents.html. (accessed September 4, 2021).

Faulring, Scott H., Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds. Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004.

Feliks, Jehuda. "Cypress." In Encyclopedia Judaica, edited by Fred Skolnik. Second ed. 22 vols. New York City, NY: Macmillan Reference, 2007. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0005_0_04781.html. (accessed August 1, 2012).

Fisk, Bruce N. Do You Not Remember? Scripture, Story, and Exegesis in the Rewritten Bible of Pseudo-Philo. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Fletcher-Louis, Crispin H. T. All the Glory of Adam: Liturgical Anthropology in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Gardner, Brant A. Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary of the Book of Mormon. 6 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007.

George, Andrew, ed. 1999. The Epic of Gilgamesh. London, England: The Penguin Group, 2003.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Harper, Elizabeth A. 2011. You shall make a tebah. First draft paper prepared as part of initial research into a doctorate on the Flood Narrative. In Elizabeth Harper’s Web Site. http://www.eharper.nildram.co.uk/pdf/makeark.pdf. (accessed June 18, 2012).

Hinckley, Gordon B. "‘If ye are prepared ye shall not fear’." Ensign 35, November 2005, 60-62.

Hodges, Horace Jeffery. "Milton’s muse as brooding dove: Unstable image on a chaos of sources." Milton Studies of Korea 12, no. 2 (2002): 365-92. http://memes.or.kr/sources/%C7%D0%C8%B8%C1%F6/%B9%D0%C5%CF%BF%AC%B1%B8/12-2/11.Hodges.pdf. (accessed August 25, 2007).

Holloway, Steven Winford. "What ship goes there: The flood narratives in the Gilgamesh Epic and Genesis considered in light of ancient Near Eastern temple ideology." Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 103, no. 3 (1991): 328-55.

Jackson, Abraham Valentine Williams. "The cypress of Kashmar and Zoroaster." In Zoroastrian Studies: The Iranian Religion and Various Monographs, edited by Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson, 255-66. New York City, NY: Columbia Press, 1928. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Zarathushtrian/cypress_zoroaster.htm. (accessed August 1, 2012).

Jackson, Kent P. The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2005. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/book-moses-and-joseph-smith-translation-manuscripts. (accessed August 26, 2016).

Jacobsen, Thorkild. "The Eridu Genesis." In The Harps That Once… Sumerian Poetry in Translation, edited by Thorkild Jacobsen. Translated by Thorkild Jacobsen, 145-50. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987.

La Torah Vivante: Les Cinq Livres de Moïse. Translated by Nehama Kohn. New York City, NY: Moznaim, 1996.

Lundquist, John M. The Temple: Meeting Place of Heaven and Earth. London, England: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

Maher, Michael, ed. Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Genesis. Vol. 1b. Aramaic Bible. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1992.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. "Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen ar)." In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 230-37. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

Matt, Daniel C., ed. The Zohar, Pritzker Edition. Vol. 1. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

McConkie, Joseph Fielding, and Craig J. Ostler, eds. Revelations of the Restoration: A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants and Other Modern Revelations. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2000.

Milton, John. 1667. "Paradise Lost." In Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, Samson Agonistes, edited by Harold Bloom, 15-257. London, England: Collier, 1962.

Morales, L. Michael. The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus. Biblical Tools and Studies 15, ed. B. Doyle, G. Van Belle, J. Verheyden and K. U. Leuven. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2012.

Müller, F. Max, ed. The Zend Avesta: The Vendidad. 3 vols. Vol. 1. Translated by James Darmesteter. The Sacred Books of the East 4, ed. F. Max Müller. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1880. Reprint, Kila, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2004.

Nibley, Hugh W. "The Babylonian Background." In Lehi in the Desert, The World of the Jaredites, There Were Jaredites, edited by John W. Welch, Darrell L. Matthews and Stephen R. Callister. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 5, 350-79. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1957. An Approach to the Book of Mormon. 3rd ed. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 6. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988.

———. 1966. "Tenting, tolling, and taxing." In The Ancient State, edited by Donald W. Perry and Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 10, 33-98. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991.

———. 1973. "Treasures in the heavens." In Old Testament and Related Studies, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 1, 171-214. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. 1980. "Before Adam." In Old Testament and Related Studies, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 1, 49-85. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Oppenheim, A. Leo. 1961. "II. The Mesopotamian temple." In The Biblical Archaeologist Reader, edited by G. Ernest Wright and David Noel Freedman. 2 vols. Vol. 1, 158-69. Missoula, Montana: Scholars Press, 1975.

Origen. ca. 200-254. "Commentary on John." In The Ante-Nicene Fathers (The Writings of the Fathers Down to AD 325), edited by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. 10 vols. Vol. 10, 297-408. Buffalo, NY: The Christian Literature Company, 1896. Reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2004.

Ouaknin, Marc-Alain, and Éric Smilévitch, eds. 1983. Chapitres de Rabbi Éliézer (Pirqé de Rabbi Éliézer): Midrach sur Genèse, Exode, Nombres, Esther. ed. Charles Mopsik. Lagrasse, France: Éditions Verdier, 1992.

Pseudo-Philo. The Biblical Antiquities of Philo. Translated by Montague Rhodes James. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), 1917. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006.

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 1: Beresheis/Genesis. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

Read, Nicholas, Jae R. Balliff, John W. Welch, BIll Evernson, Kathleen Reynolds Gee, and Matthew Roper. 1992. "New light on the shining stones of the Jaredies." In Pressing Forward with the Book fo Mormon: FARMS Updates of the 1990s, edited by John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne, 253-55. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) at Brigham Young University, 1999.

. 2 vols. 3ième ed. Paris, France: Dictionnaires Le Robert, 2000.

La Caverne des Trésors: Les deux recensions syriaques. 2 vols. Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 486-487 (Scriptores Syri 207-208). Louvain, Belgium: Peeters, 1987.

Robinson, Stephen E., and H. Dean Garrett. A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants. 4 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2001-2005.

Sailhamer, John H. "Genesis." In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelein, 1-284. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990.

Schwartz, Howard. Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Seixas, Joshua. A Manual of Hebrew Grammar for the Use of Beginners. Second enlarged and improved ed. Andover, MA: Gould and Newman, 1834. Reprint, Facsimile Edition. Salt Lake City, UT: Sunstone Foundation, 1981. https://books.google.com/books/about/A_manual_Hebrew_grammar_for_the_use_of_b.html?id=fN1GAAAAMAAJ. (accessed August 31, 2020).

Sherlock, Richard. "Response to Professor McCann." In Mormonism in Dialogue with Contemporary Christian Theologies, edited by Donald W. Musser and David L. Paulsen, 92-111. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007.

Silverman, Jason M. "It’s a craft! It’s a cavern! It’s a castle! Yima’s Vara, Iranian flood myths, and Jewish apocalyptic traditions." In Opening Heaven’s Floodgates: The Genesis Flood Narrative, Its Context and Reception, edited by Jason M. Silverman. Bible Intersections 12, 191-230. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2013.

Smith, Joseph, Jr., Andrew F. Ehat, and Lyndon W. Cook. The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/book/words-joseph-smith. (accessed August 21, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

Smith, Mark S. The Priestly Vision of Genesis 1. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2010.

Sparks, Jack Norman, and Peter E. Gillquist, eds. The Orthodox Study Bible. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2008.

Tissot, J. James. The Old Testament: Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, Parts 1 and 2. 2 vols. Paris, France: M. de Brunhoff, 1904.

Triolo, Joseph. 2019. The Tabernacle as Structurally Akin to Noah’s Ark: Considering Cult, Cosmic Mountain, and Diluvial Arks in Light of the Gilgamesh Epic and the Hebrew Bible (Paper presented at the Pacific Coast Regional Meeting of SBL. Fullerton, CA, 10 March 2019). In Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/38869031/_The_Tabernacle_as_Structurally_Akin_to_Noahs_Ark_Considering_Cult_Cosmic_Mountain_and_Diluvial_Arks_in_Light_of_the_Gilgamesh_Epic_and_the_Hebrew_Bible_Paper_presented_at_the_Pacific_Coast_Regional_Meeting_of_SBL. (accessed September 10, 2021, 2021).

Tvedtnes, John A. "Glowing stones in ancient and medieval lore." Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 6, no. 2 (1997): 99-123.

Walton, John H. Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2011.

Wenham, Gordon J., ed. Genesis 1-15. Word Biblical Commentary 1: Nelson Reference and Electronic, 1987.

Westermann, Claus, ed. 1974. Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary 1st ed. Translated by John J. Scullion. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1994.

Wevers, John William. Notes on the Greek Text of Genesis. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993.

Wintermute, O. S. "Jubilees." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. Vol. 2, 35-142. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Wyatt, Nicolas. "’Water, water everywhere…’: Musings on the aqueous myths of the Near East." In The Mythic Mind: Essays on Cosmology and Religion in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicholas Wyatt, 189-237. London, England: Equinox, 2005.

Zlotowitz, Meir, and Nosson Scherman, eds. 1977. Bereishis/Genesis: A New Translation with a Commentary Anthologized from Talmudic, Midrashic and Rabbinic Sources 2nd ed. Two vols. ArtScroll Tanach Series, ed. Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1986.

Endnotes

… that if each deck were further subdivided into three sections (cf. Gilgamesh’s nine sections (A. George, Gilgamesh, 11:62, p. 90), the Ark would have had three decks the same height as the Tabernacle and three sections on each deck the same size as the Tabernacle courtyard.

Regarding similarities in the Genesis 1 account of Creation, the Exodus 25ff. account of the building of the Tabernacle, and the account of the building of the ark, Sailhamer writes (J. H. Sailhamer, Genesis, p. 82, see also table on p. 84):

Each account has a discernible pattern: God speaks (wayyo’mer/wayedabber), an action is commanded (imperative/jussive), and the command is carried out (wayya’as) according to God’s will (wayehi ken/kaaser siwwah ‘elohim). The key to these similarities lies in the observation that each narrative concludes with a divine blessing (wayebarek, Genesis 1:28, 9:1; Exodus 39:43) and, in the case of the Tabernacle and Noah’s Ark, a divinely ordained covenant (Genesis 6:8; Exodus 34:27; in this regard it is of some importance that later biblical tradition also associated the events of Genesis 1-3 with the making of a divine covenant; cf. Hosea 6:7). Noah, like Moses, followed closely the commands of God and in so doing found salvation and blessing in his covenant.

The sentence “and the ark went on the face of the waters” (Genesis 8:18) is not suited to a boat, which is navigated by its mariners, but to something that floats on the surface of the waters and moves in accordance with the thrust of the water and wind. Similarly, the subsequent statement (Genesis 8:4) “the ark came to rest… upon the mountains of Ararat” implies an object that can rest upon the ground; this is easy for an ark to do, since its bottom is straight and horizontal, but not for a ship.

Atonement translates the Hebrew kpr, but the meaning of kpr in a ritual context is not known. Investigations have uncovered only what actions were used in the rites of atonement, not what that action was believed to effect. The possibilities for its meaning are “cover” or “smear” or “wipe,” but these reveal no more than the exact meaning of “breaking bread” reveals about the Christian Eucharist…. I should like to quote here from an article by Mary Douglas published… in Jewish Studies Quarterly (M. Douglas, Atonement, p. 117. See also M. Douglas, Leviticus, p. 234: “Leviticus actually says less about the need to wash or purge than it says about ‘covering.’”):

Terms derived from cleansing, washing and purging have imported into biblical scholarship distractions which have occluded Leviticus’ own very specific and clear description of atonement. According to the illustrative cases from Leviticus, to atone means to cover or recover, cover again, to repair a hole, cure a sickness, mend a rift, make good a torn or broken covering. As a noun, what is translated atonement, expiation or purgation means integument made good; conversely, the examples in the book indicate that defilement means integument torn. Atonement does not mean covering a sin so as to hide it from the sight of God; it means making good an outer layer which has rotted or been pierced.

This sounds very like the cosmic covenant with its system of bonds maintaining the created order, broken by sin and repaired by “atonement.”

Those who saw Aronofsky’s disappointing 2014 film version of the story of Noah will remember the character Tubal-Cain’s relentless quest to amass wealth through the mining of a luminous mineral called tsohar. See the review of the film in J. M. Bradshaw, Noah Like No Other.

Research in radioluminescence has provided insights into some of the possibilities by which light could be generated over long periods without an external power source (N. Read et al., New Light).

The most wonderful thing about Jerusalem the Holy City is its mobility: at one time it is taken up to heaven and at another it descends to earth or even makes a rendezvous with the earthly Jerusalem at some point in space halfway between. In this respect both the city and the temple are best thought of in terms of a tent, … at least until the time comes when the saints “will no longer have to use a movable tent” [Origen, John, 10:23, p. 404. “The pitching of the tent outside the camp represents God’s remoteness from

the impure world” (H. W. Nibley, Tenting, p. 79 n. 40)] according to the early Fathers, who get the idea from the New Testament… [E.g., “John 1:14 reads literally, ‘the logos was made flesh and pitched his tent [eskenosen] among us’; and after

the Resurrection the Lord ‘camps’ with his disciples, Acts 1:4. At the Transfiguration Peter prematurely proposed setting up three tents for taking possession (Matthew 17:4; Mark 9:5; Luke 9:33)” (ibid., p. 80 n. 41] It is now fairly certain, moreover, that the great temples of the ancients were not designed to be dwelling-houses of deity but rather stations or landing-places, fitted with inclined ramps, stairways, passageways, waiting-rooms, elaborate systems of gates, and so forth, for the convenience of traveling divinities, whose sacred boats and wagons stood ever ready to take them on their endless junkets from shrine to shrine and from festival to festival through the cosmic spaces. The Great Pyramid itself, we are now assured, is the symbol not of immovable stability but of constant migration and movement between the worlds; and the ziggurats of Mesopotamia, far from being immovable, are reproduced in the seven-stepped throne of the thundering sky-wagon.

Some Christians came to view Psalm 18 as foreshadowing the Incarnation of God’s son (J. N. Sparks et al., Orthodox Study Bible, p. 691 n. 17). Noah’s Ark was sometimes seen in a similar fashion: “The ark was a type of the Mother of God with Christ and the Church in her womb (Akath). The flood-waters were a type of baptism, in which we are saved (1 Peter 3:18-22)” (ibid., Genesis 6:14-21, p. 12).

Consistent with this reading that understands this verse as a period of divine preparation, the creation story in the Joseph Smith’s book of Abraham employs the term “brooding” rather than “moving” as we find in the King James Version. Note that this change is consistent with the English translation given Hebrew grammar book that was studied by Joseph Smith in Kirtland (see J. Seixas, Manual, p. 31). John Milton (J. Milton, Paradise Lost, 1:19-22, p. 16; H. J. Hodges, Dove; cf. Augustine, Literal, 18:36; E. A. W. Budge, Cave, p. 44) interpreted the passage similarly in Paradise Lost, drawing from images such as the dove sent out by Noah (Genesis 8:6-12), the dove at Jesus’ baptism (John 1:32), and a hen protectively covering her young with her wing (Luke 13:34):

[T]hou from the first

Wast present, and with mighty wings outspread

Dovelike satst brooding on the vast abyss

And mad’st it pregnant.”

“Brooding” enjoys rich connotations, including, as Nibley observes (H. W. Nibley, Before Adam, p. 69), not only “to sit or incubate [eggs] for the purpose of hatching” but also:

… “to dwell continuously on a subject.” Brooding is just the right word—a quite long quiet period of preparation in which apparently nothing was happening. Something was to come out of the water, incubating, waiting—a long, long time.

Some commentators emphatically deny any connection of the Hebrew term with the concept of brooding (e.g., U. Cassuto, Adam to Noah, pp. 24-25). However, the “brooding” interpretation is not only attested by a Syriac cognate (F. Brown et al., Lexicon, 7363, p. 934b) but also has a venerable history, going back at least to Rashi who spoke specifically of the relationship between the dove and its nest. In doing so, he referred to the Old French term acoveter, related both to the modern French couver (from Latin cubare—to brood and protect) and couvrir (from Latin cooperire—to cover completely). Intriguingly, this latter sense is related to the Hebrew term for the atonement, kipper (M. Barker, Atonement; A. Rey, Dictionnaire, 1:555).

Going further, Barker admits the possibility of a subtle wordplay in examining the reversal of consonantal sounds between “brood/hover” and “atone”: “The verb for ‘hover’ is rchp, the middle letter is cheth, and the verb for ‘atone’ is kpr, the initial letter being a kaph, which had a similar sound. The same three consonantal sounds could have been word play, rchp/kpr” (M. Barker, June 11 2007). “There is sound play like this in the temple style” (ibid.; see M. Barker, Hidden, pp. 15-17). In this admittedly speculative interpretation, one might see an image of God, prior to the first day of Creation, figuratively “hovering/atoning” [rchp/kpr] over the singularity of the inchoate universe, just as the Ark smeared with pitch [kaphar] later moved over the face of the waters “when the waters cover[ed] over and atone[d] for the violence of the world” (E. A. Harper, You Shall Make, p. 4).

7 days of waiting for flood (7:4)

7 days of waiting for flood (7:10)

40 days of flood (7:17a)

150 days of water triumphing (7:24)

150 days of water waning (8:3)

40 days of waiting (8:6)

7 days of waiting (8:10)

7 days of waiting (8:12)

The description of God’s rescue of Noah foreshadows God’s deliverance of Israel in the Exodus. Just as later “God remembered his covenant” (Exodus 2:24) and sent “a strong east wind” to dry up the waters before his people (Exodus 14:21) so that they “went through… on dry ground” (Exodus 14:22), so also in the story of the Flood we read that “God remembered” those in the ark and sent a “wind” over the waters (Genesis 8:1) so that his people might come out on “dry ground” (Genesis 8:14).