Abstract: Latter-day Saint scholars generally agree that “the place called… Nahom,” where Ishmael was buried (1 Nephi 16:34) is identified as the Nihm tribal region in Yemen. Significantly, a funerary stela with the name y s1mʿʾl — the South Arabian equivalent of Ishmael — was found near the Nihm region and dated to ca. 6th century bc. Although it cannot be determined with certainty that this is the Ishmael from the Book of Mormon, circumstantial evidence suggests that such is a possibility worth considering.

In recent decades, Latter-day Saint scholars have come to identify Nahom — the burial place of Ishmael, Nephi’s father-in-law (1 Nephi 16:34) — with the Nihm tribal region in Yemen.1 The exact borders of the Nihm tribal area have fluctuated over time, but it has been located near the Wadi Jawf since the early Islamic era.2 Several inscriptions referring to individuals as nhmyn (“Nihmite”) confirm the tribe existed at least by the seventh century bc,3 and based on these texts scholars generally believe the Nihm tribe were in a region near the Jawf in antiquity.4

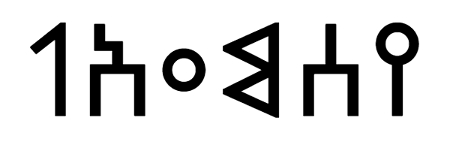

It is noteworthy, therefore, that in 2008 a corpus of over 400 crudely carved funerary stelae recovered from the Wadi Jawf were published by the Sanaʿa National Museum.5 These stelae have anthropomorphic facial features carved above an inscription of the name of the deceased. This is a pan-Arabian style of funerary stela, with this particular corpus featuring some distinctive regional variations unique to the Wadi Jawf.6 Among these is a 30 cm (ca. 1 ft.) x 12.5 cm (ca. 5 in.) x 7.5 cm (ca. 3 in.) limestone stela with a roughly incised face outline (eyes, a nose, mouth, and jaw-line), below which is inscribed the name y s1mʿʾl in Epigraphic South Arabian, translated as “Yasmaʿʾīl” (see Figure 1).7 The stela is paleographically dated to 6th–5th centuries bc, but Mounir Arbach and his co-authors consider it stylistically among “a few coarse examples” [Page 34]of the incised face elements stela type “known for the 7th–6th centuries bc.”8

Figure 1. Funerary stela YM 27966 bearing the name Y s1MʿʾL, equivalent to the Hebrew name “Ishmael,” dated to ca. 6th century bc.9

The name Yasmaʿʾīl is the South Arabian form of the name Ishmael, even though the two names may look somewhat different in translation.10 The inscribed y s1mʿʾl is exactly how the Hebrew name yšmʿʾl (ישמעאל) — typically rendered as “Ishmael” in English — would be spelled in Epigraphic South Arabian.11 In fact, the two names have the exact same etymology, meaning “God has heard/hearkened,” or “may God hear,”12 and in The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, the Old South Arabian y s1mʿʾl is listed as an equivalent to the Hebrew name yšmʿʾl (Ishmael).13 Thus, this stela indicates that a man named the equivalent of Ishmael was buried in or near the Wadi Jawf around the 6th century bc, about the same time period Ishmael was buried at Nahom, according to the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi 16:34).

[Page 35]

Figure 2. The name “Ishmael” (Yasmaʿʾil) in Old South Arabian script.

Connection to the Nihm?

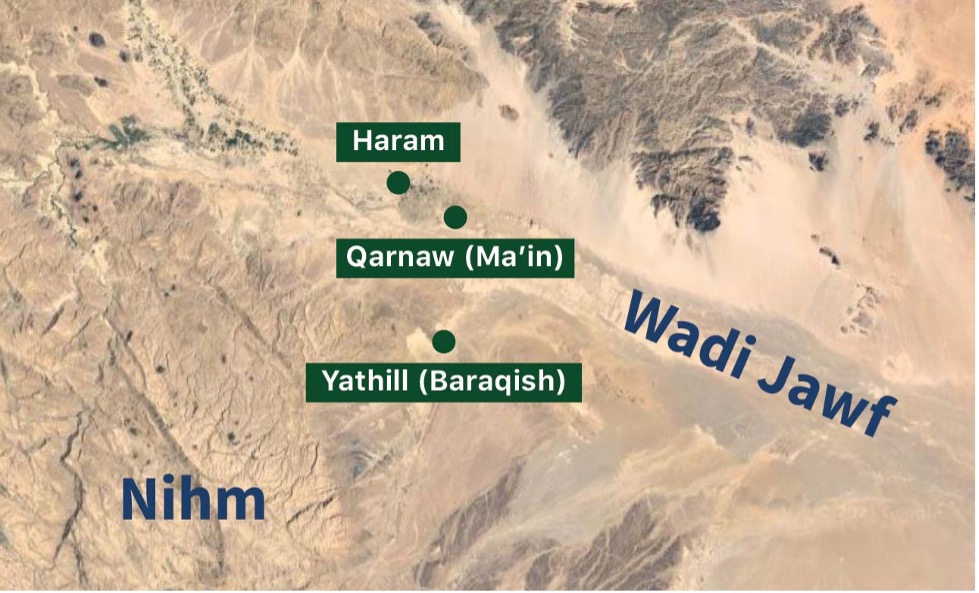

Unfortunately, this funerary stela and the rest of this particular corpus were looted from their original context and recovered on the antiquities market, so they lack clear provenance. The authenticity of these stelae is not doubted,14 but this means it is impossible to know exactly where they came from and if that location had any connection to the Nihm tribe. However, a separate collection of 40 funerary stelae of the same style were recovered in situ at the ancient site of Yathill (modern-day Barāqish), one of the ancient city-states of the Jawf.15 Barāqish is associated with the modern-day Nihm tribe,16 so it is possible some of the looted stelae also came from areas connected to the Nihm.

Figure 3. Map of the Wadi Jawf.

Interestingly, some of the looted stelae are believed to come from Haram, another one of the Jawf city-states.17 Stelae of a similar style were previously recovered at Haram, and taken as evidence that people from [Page 36]“Arab” tribes north of the Jawf were present at Haram from the very earliest period of South Arabian history.18 Three identical inscriptions from this location, all dated to the 7th century bc, mention a man named ʿAmmīʾanas, who is called the kbr nh[m]tn, meaning the “chief” or “tribal leader” (kbr) of a group called NHMTN.19 Christian Robin translates nhmtn here as “the stone polishers” (des tailleurs de pierre),20 while G. Lankester Harding considered NHMTN in these inscriptions to be a proper name, most likely the name of a “tribe or people.”21 Another 7th century bc inscription (from an unknown location) identifies a man named Halakʾamar and his father ʾIlīdharaʾ both as kbr nhmt; in this inscription, NHMT is understood as a reference to a tribe and Herrmann von Wissmann identified it as the Nihm.22 If the NHMTN are the same group as the NHMT, these inscriptions may thus suggest a link between Haram and Nihm in Lehi’s day.23 Significantly, Haram was only about 4 miles west of Maʿin (ancient Qarnaw), where a branch of the ancient Frankincense Trail cut across the desert eastward (cf. 1 Nephi 17:1).24

A Foreigner or Caravan Traveler?

The background and origin of the population associated with funerary stelae of this style is currently uncertain, with at least two competing hypotheses. Based on the archaeological context of the corpus from Yathill (Barāqish), Sabina Antonini and Alessio Agostini argue that they come from an “outsider” group, who “were connected in some way with the town of Barāqish, but that they were not in effect members of the community.” Most likely, “they were caravaneers engaged in commerce throughout the western side of the Peninsula,”25 or potentially “foreigners who certainly had some sort of contact with the inhabitants of Barāqish” and had “developed relationships with the sedentary inhabitants of the city but did not ‘officially’ belong there.”26

Mounir Arbach, Jérémie Schiettecette, and Ibrâhîm al-Hâdî, on the other hand, argue that the looted stelae from the Jawf were a product of the lower strata of local populations, based on the generally crude and inexpert nature of the carvings and inscriptions.27 These two points of view are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as Arbach et al. allow for the possibility that “a small number” represent the “deceased of a different cultural origins,” specifically, “caravan traders, nomads, Mineans established in Northern Arabia, [and] Central or Northern Arabian populations.”28 Thus, the Ishmael or Yasmaʿʾīl of this stela was either a local individual of lower social status or a foreigner from the north [Page 37]traveling along the major trade route, perhaps with some connection to the populations in and around the Wadi Jawf.

The Name Ishmael/Yasmaʿʾil

One of the ways the origins of these stelae are assessed is through onomastics (the names on the stelae).29 An analysis of the onomastics found on the stelae from Barāqish indicated there were several links to Northwest Semitic and North Arabian names, strengthening the hypothesis that these individuals were involved in the caravan trade.30 Hugh Nibley believed that the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon had Arabian links, based on his name,31 but today the evidence is actually pointing in the opposite direction. The name Ishmael is of Northwest Semitic origins, and well attested in Hebrew tradition, both in the Old Testament — which mentions five other Ishmaels besides the son of Abraham and Hagar — and in the epigraphic sources from the 8th to 6th centuries bc.32 In fact, Ishmael “was a very popular name in the 7th and 6th centuries [bc]” in Judah.33 In contrast, in South Arabia, Ishmael (y s1mʿʾl) was uncommon at this time. Out of 28 attestations of the name in the Corpus of South Arabian Inscriptions (CSAI), only four are dated to the Early Sabaic Period (ca. pre-4th century bc).34 Thus, rather than pointing to Arabian origins, the name Ishmael is an appropriate Hebrew name, and potentially indicates that the Yasmaʿʾil buried in the Yemeni Jawf was a foreigner from the north, where his Semitic name originated and was more common.

Lehi’s Family and South Arabian Writing and Burial Customs

Since this stela is in a thoroughly Arabian style and the inscription is in Epigraphic South Arabian, some may wonder if Israelites from Jerusalem, such as Lehi and his family, would be likely to adopt such foreign practices in their burial customs. Iron age burial practices in Judah and Israel largely mirror those of their neighbors in Palestine,35 and later Jews of the Second Temple Period also frequently incorporate the burial traditions of their surrounding culture.36 So, it is not unreasonable to suppose that while traveling through Arabia, likely along the major caravan route,37 Lehi and his family may have adopted burial practices common to local populations or fellow caravan travelers.

The fact that the inscription is in Epigraphic South Arabian, however, does raise the question of whether Lehi’s family had learned the local language and script. When making arrangements for Ishmael’s burial, it is plausible that Lehi’s family hired a local stone carver (perhaps [Page 38]from the Nihm tribe) to make the stela and inscribe it with Ishmael’s name; in light of the clear (albeit crude) execution of local style and script, this is perhaps the more likely hypothesis. Nonetheless, there are some indications that Lehi’s family may have learned South Arabian languages. Certainly, learning the name “Nahom” and arranging with the local population for the proper burial of Ishmael would have required at least learning the spoken language. Furthermore, some scholars have proposed a South Arabian etymology for the name Irreantum, suggesting that Lehi’s family had become conversant in the local languages.38

More specifically suggesting knowledge of Epigraphic South Arabian script is an unpublished study of the Book of Mormon “Caractors” document indicating that some of the symbols bear resemblance to North and South Arabian characters.39 S. Kent Brown also argued that Lehi’s family may have spent time in servitude in South Arabia.40 If that is true, then the skilled labor of Nephi and Lehi (and perhaps others in the party), who could both write and work in metals (and write on metals),41 likely would have been one of their best assets as servants to tribal overlords, requiring them to learn the language.42

Could this be Ishmael from the Book of Mormon?

Ultimately, there is not enough evidence to make a positive identification with the Yasmaʿʾil of this funerary stela and the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon. The most that can be said is that there was an Ishmael, buried near the Nihm tribal region, around the 6th century bc. The lack of further identifying information in the inscription (such as a patronym) or the Book of Mormon text, and the inability to determine with certainty if the stela in question was found within or merely near the Nihm tribal region, makes a more definitive association impossible.

Still, the possibility is tantalizing. The Yasmaʿʾil of this funerary stela was buried somewhere within or near the Wadi Jawf, ca. 6th century bc, possibly at a site (Haram) which some inscriptions suggest had a connection with the Nihm in Lehi’s day. The name Yasmaʿʾil and the style of stela are suggestive of (but not definitive evidence for) a foreigner from the north, associated with the caravan trade. Ishmael was buried at Nahom — identified as the Nihm tribal area, near the Wadi Jawf — in the early 6th century bc, and had arrived in the area from the north, most likely traveling along the major caravan route. Thus, the general profiles of the two Ishmaels fit, at least in broad strokes. At the very least, it seems reasonable to suggest that if the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon was buried with some sort of identifying marker, it probably would [Page 39]have looked something like the Yasmaʿʾil stela — a crudely carved stela typical of foreigners traveling through the area, who lacked substantial time or resources to afford a more extravagantly carved and engraved burial stone.

Although a firmer conclusion eludes us, the very fact that an Ishmael was buried in close proximity to the Nihm tribal region around the very time the Book of Mormon indicates that a man named Ishmael was buried at Nahom is rather remarkable. Such a fact certainly does not weaken the case for the Book of Mormon’s historicity.

Go here to see the 8 thoughts on ““An Ishmael Buried Near Nahom”” or to comment on it.