Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the last in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

After summarizing the strongest pieces of evidence we’ve considered in our statistical journey, we discuss what we can conclude from our Bayesian analyses. Though that evidence doesn’t represent unassailable proof for the Restoration and all it entails, what it does is show how belief in an authentic Book of Mormon can be reasonable, which supports further reasoned belief in God and Christ. But reasons to believe do not necessarily correspond with reasons to live by the teachings of the Church in the modern day. The Book of Mormon can help provide those latter reasons, but the best way to know their truth is to live them. Figuring out how to do that is likely to be a better use of our time and energy than continually re-appraising Book of Mormon authenticity.

NET OVERALL EVIDENCE SCORE: 69 orders of magnitude in favor of authenticity.

The Narrative

When last we left you, our ardent skeptic, you had finished turning over the possibilities of finding yet another book of scripture, one that came from the same mind that allegedly produced the one that still sat in your pack. But as intriguing as those possibilities are, they aren’t what you came here to do. You turn to the clerk as you’re about to leave the store. “Say, have you seen that young man about, the one peddling a book?”

The clerk gives a small sigh and a roll of his eyes. “The one with the golden bible? He was in here this morning, though I’m not sure what’s keeping him in town. Word is he’s got a room at the inn for one more night.” The sigh turned quickly to a grin. “If you want to lash him with that silver tongue of yours, I’m betting you can still catch him.”

You return the grin halfheartedly and bid the clerk a quick farewell with a tip of your hat. Your thoughts the last few days had given you plenty to lash with, though some of them might turn to lash your own softening hide. You have no idea what you want say to the young man, but you know you want to say it quickly. It only takes a few minutes to guide your wagon to the town’s only inn.

The innkeeper seems similarly annoyed at the presence of his book-wielding guest. “I’m not sure why you’d want to spare more than two words for the man, but you’ll get your chance if you’re willing to wait. He took his golden bible off on some fool’s errand, but said he’d be back after lunch.”

And so you take a refreshingly comfortable sit in one of the small foyer’s upholstered chairs. A little time to sit and wait is just what you need. You’d considered never actually finishing the last few pages of the book itself—you feel that you’d read quite enough to make up your mind one way or another—but to put it down at this point would grate at every part of your literature-loving soul. You ignore the quizzical look on the innkeeper’s face as you pull out this apparently infamous “golden bible,” and quickly find the place where you’d left off.

You’re somewhat surprised to read yet more words from Moroni, supposed son of the book’s namesake, as he’d already signed off several chapters back. His unexpected return reminded you of novels you’d read with a few too many endings. You can’t help but find this aside interesting, even if it mostly consists of administrative instructions for the operation of the church.

But it’s the last chapter that really gets your attention:

And I seal up these records, after I have spoken a few words by way of exhortation unto you.

It strikes you that, despite your intense reading, you’d been too busy trying to figure out whether the book was actually authentic to pay much attention to what the book was actually saying. You suppose this is probably your last chance to get a sense of what this Moroni actually wanted you to do.

Go on Moroni, you think to yourself. Hit me with your best shot.

I would exhort you that when ye shall read these things, if it be wisdom in God that ye should read them, that ye would remember how merciful the Lord hath been unto the children of men…

You almost have to stifle an angry, mirthless laugh at that line. If there was a God, you hadn’t seen much in the way of mercy from him in some time. Had he been merciful to your wife and children, lost now these many years? Had he even been merciful to the people in this book, who’d been slaughtered to the last man? How? you exclaim to yourself. How has the Lord been merciful?

I would exhort you that ye deny not the power of God…And again, I would exhort you, my brethren, that ye deny not the gifts of God, for they are many; and they come from the same God.

What power, what gifts could he be talking about here? The gift of a short, cruel existence with an often painful and merciless end? If there was something that he’d been given from God, he’d been denying for a bit now without consequence. These miracles and spiritual gifts he went on to refer to, and that the apostle Paul had already spoken of so eloquently—what evidence had there been for them in those long centuries besides the quaking you’d seen at camp meetings? How? you ask again. How can I not deny the gifts of God?

I would exhort you, my beloved brethren, that ye remember that every good gift cometh of Christ.

This one seems manifestly untrue to you. Sure, God could be responsible for many of the good things he’d seen and experienced, but there are so many things in your life that needn’t have come from an all-powerful God or benevolent savior–so many things that humanity had given themselves without God’s help. How? How could all good gifts come from Christ?

You realize, though, that you’d missed one as your eye had scanned the page. You move up a few verses to find another exhortation:

I would exhort you that ye would ask God, the Eternal Father, in the name of Christ, if these things are not true; and if ye shall ask with a sincere heart, with real intent, having faith in Christ, he will manifest the truth of it unto you, by the power of the Holy Ghost.

At that one you stop. You think back to everything you had read, and through all that there was one thing you couldn’t deny—this was a strange book, a book that you had a hard time seeing a complete and ready explanation for. Could Smith have really pushed this thing whole cloth out of his head? You’re no longer nearly as sure as you were when you first cracked open the book’s pages.

But you wonder at what Moroni is asking you to do here. You’d already been weighing the evidence at your disposal—surely that was the best way to draw a conclusion about the book, rather than trying to receive a subjective answer to prayer. What value could that have that the evidence itself couldn’t provide? How? The question keeps pounding in your mind. How could he manifest that truth?

I would exhort you, my beloved brethren, that ye remember that he is the same yesterday, today, and forever, and that all these gifts of which I have spoken, which are spiritual, never will be done away.

That was an interesting one. One thing that had puzzled you, even when you had faith, is how the vengeful God of the Old Testament could square with the compassionate, forgiving God of the New. The two seemed at such odds that the gap could never be crossed. Yet your mind, almost of its own accord, casts back to the book. This book purported to span both the Old and New testaments, connecting them in a way that intrigued you, with elements of both Gods present and yet unified in its pages. How? you wonder, more inquisitive than insistent. How can those Gods be the same god?

I exhort you to remember these things; for the time speedily cometh that ye shall know that I lie not, for ye shall see me at the bar of God; and the Lord God will say unto you: Did I not declare my words unto you, which were written by this man, like as one crying from the dead, yea, even as one speaking out of the dust?

That sentence hits you with a power you hadn’t expected. That power turns inward on you, leading you to a thought that feels at the same time foreign and familiar. If there was a God, and there was a Moroni, how would you see yourself when you got to that judgment bar? Would you be happy with what you saw, with the person you are, standing exposed in the full light of truth? That was a question you hadn’t asked yourself in a long time, and it seemed relevant regardless of whether or not he actually would come face-to-face with Moroni. How? you ask, now with a very different flavor of ‘how’. How would I be seen at the bar of God?

I would exhort you that ye would come unto Christ, and lay hold upon every good gift…yeah come unto Christ, and be perfected in him, and deny yourselves of all ungodliness; and if you shall deny yourselves of all ungodliness, and love God with all your might, mind, and strength, then is his grace sufficient for you, that by his grace you may be perfect in Christ.

As you read those words you can almost feel the impossibilities underlying them. You realize that you don’t know how perfection could be possible, how someone could really deny themselves of all ungodliness, how anyone could give all of their might, mind, and strength. Never, even in your most spiritual of mindsets, did you see a path for that to come to pass. Humanity was just too flawed, too fallen.

You expect your thoughts to stop there, but they don’t. It seemed impossible, yes. But so too did the idea that this book, after all you’d seen, was the product of a single nineteenth-century mind. If you lived in a universe where that was possible, you lived in a universe where anything was possible. If Joseph could reach that far above every indication of his own natural ability, why couldn’t humanity reach the heights that Moroni spoke of, through the grace of a loving God?

It’s also possible, of course, that you’re just missing something, that there’s a perfectly reasonable explanation for this book that you just can’t see. But, then again, maybe there’s something within the heart of man, within the mind of God—within your own heart and your own mind—that you can’t see either.

How? you ask, one final time—it was a plea, almost a prayer. How could I—how could anyone—be perfected in Christ?

The plea echoes through you as you sit, waiting for your quarry to arrive.

The Commentary

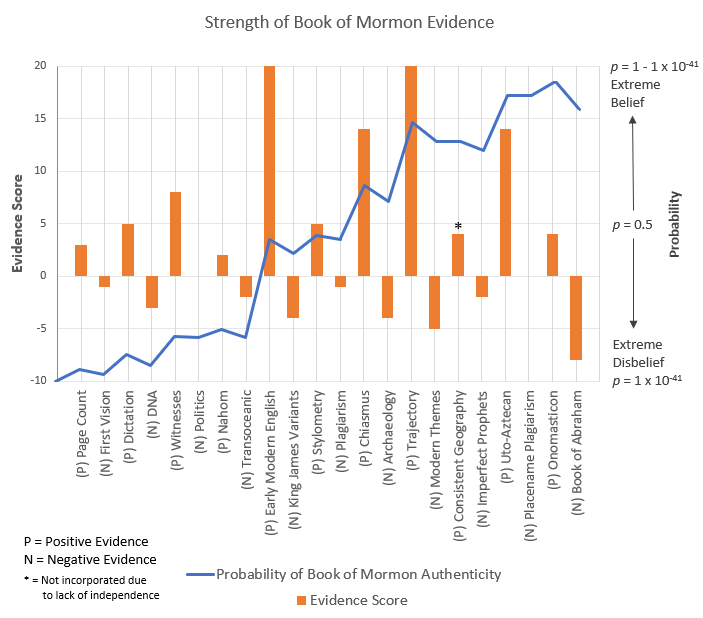

Congratulations on reaching the end of our little journey. The evidence, for our purposes, is now in. Let’s take a look at how that evidence has shaken out over the last 22 episodes:

The orange bars show us the estimated strength of the evidence presented in each episode. Remember, we don’t mean strength in the sense that evidence and the conclusions drawn from it are unassailable and uncontroversial—we mean it in purely in the sense that the evidence we have, as little and uncertain as it might be in some cases, differs from what we’d expect—the (metaphorical) distance away from what we would otherwise assume to be the case under the conditions of our hypotheses. In that sense we can see quite clearly that the Book of Mormon is unexpected. Tallying all of our evidence up—summing all the scores for each piece of evidence, both positive and negative—gives us an overall evidence score of 69—increasing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by a nearly unfathomable number of times. We can also see where the strongest and most unusual evidence seems to lie. I’ve laid them out in the table below from the strongest to weakest. (See the Appendix for a brief summary of each analysis.)

| Evidence | Evidence Score |

|---|---|

| (P) Early Modern English | 20+ |

| (P) Trajectory | 20 |

| (P) Chiasmus | 14 |

| (P) Uto-Aztecan | 14 |

| (P) Witnesses | 8 |

| (N) Book of Abraham | -8 |

| (P) Dictation | 5 |

| (P) Stylometry | 5 |

| (N) Modern Themes | -5 |

| (N) King James Variants | -4 |

| (N) Archaeology | -4 |

| (P) Consistent Geography | 4 |

| (P) Onomasticon | 4 |

| (P) Page Count | 3 |

| (N) DNA | -3 |

| (P) Nahom | 2 |

| (N) Transoceanic | -2 |

| (N) Imperfect Prophets | -2 |

| (N) First Vision | -1 |

| (N) Plagiarism | -1 |

| (N) Politics | 0 |

| (N) Placename Plagiarism | 0 |

Note that in putting this list together, I tried my best to exhaust the independent critical arguments against the Book of Mormon. But I didn’t exhaust the arguments on the faithful side. I did that to try to make sure the playing field was even, with each faithful ying matched with a critical yang, so that no one could accuse me of tilting the scales with a dogpile of weak evidence. If I’d wanted to, though, there’s at least three additional areas of positive evidence that I could’ve worked into this analysis, and I’ll touch on them briefly:

The Book of Moses. Though critics like to have a field day with the Book of Abraham, there’s a reason you don’t often see them saying a ton about the Book of Moses. There are a very healthy number of ancient connections that can be drawn from the book, foremost among them being somewhat startling parallels with the pseudepigraphal Enoch 1, Enoch 2, and the Book of Giants, some of which Joseph wouldn’t have had access to. A Bayesian analysis of the book’s strengths and weaknesses would almost certainly push the overall evidence even further into the column of authenticity.

The Lost 116 Pages. The story of the lost 116 pages has become perennial (or at least quadrennial) among Latter-Day Saints, but that familiar cautionary tale, and the missing portion of the Book of Mormon associated with it, has recently been given new life through the work of historian Don Bradley. His keen insights help demonstrate that these manuscript pages existed, and that their likely contents could have shown the same ancient threads as the rest of the book. It would certainly have been interesting to mine Bradley’s book for useful (and independent) evidence for (or against) the Book of Mormon’s authenticity.

The Caractors (sic) Document. Many critics emphasize the fact that we no longer have the gold plates, but few emphasize that we actually do have a sample of the characters that were present on the plates, as obtained by David Whitmer. I referred briefly in my episode on the Book of Mormon Onomasticon to the fact that similar characters transcribed by Frederick G. Williams actually seem to spell out the word “Book of Mormon” in Demotic Egyptian, but the evidentiary value of these copied characters potentially goes much deeper. Though most critics insist the characters are nonsense, these hand-waving reactions are countered by an extremely compelling amateur analysis from Jerry Grover, one that ties each character to a mixture of Demotic, Hebrew, and Mesoamerican characters, including numerical and calendrical markings (i.e., exactly what one would expect from a “Reformed Egyptian”). Even more surprisingly, translating those characters doesn’t produce the hodgepodge of nonsense one might expect, but a rather coherent summary of the content of the Book of Mormon itself. Regardless of how valid those connections turn out to be, the lack of mainstream scholarly attention the Caractors Document has received—the only primary source for the Book of Mormon in existence—borders on criminal. Grover’s work would be ripe for an (exceedingly difficult) Bayesian analysis.

But among the evidence I did examine, the standout favorite–the area where the greatest challenge seems to lie for the critics–is evidence related to Early Modern English. Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack have done a careful and considered job laying out the lexical and syntactic evidence placing the Book of Mormon outside the hands of Joseph or anyone else in the late modern era. It would take a heroic effort on the critical end to undo what they’ve put together.

The other critical strike, from my point of view, is how the evidence has appeared to increasingly side with the faithful perspective, particularly in the last few decades. I just don’t see how a fraud as audacious as the Book of Mormon looks more authentic the more its examined—with as much attention as it’s gotten, silver bullets should have been flying out of the woodwork, and they sure seemed to be, until further exploration and technological advancements patiently and consistently demonstrated otherwise. In no universe would I expect 70% of a fraudulent book’s criticisms to be overturned. With the book being proven right and the experts proven wrong dozens of times, just maybe we can conclude that it’s right across the board, despite the criticisms and questions that remain.

By this point it’s possible that critics (and even many faithful scholars) are deaf to the idea of chiasmus as useful evidence in favor of the Book of Mormon. But though chiasmus can occur on the basis of chance, the sheer density (as well as the distribution) of chiastic forms in the book may be more than chance can deal with. Some can insist that Joseph merely “had a good ear” for biblical Hebrew poetry, but my analysis suggests that having such a good ear would itself be extremely unexpected. It doesn’t constitute a critical strike, but no other pseudo-biblical work in Joseph’s era appears to come anywhere close to what we see in the Book of Mormon.

Though also not a critical strike, I find the evidence compiled from Brian Stubbs on connections between Egyptian, Hebrew, and Uto-Aztecan to be extremely compelling, and I’m not the only one. That others aren’t as convinced is perhaps to be expected, though of course those criticisms should be taken seriously. From my own hard look at his data, what Stubbs has given us more than exceeds what would be expected on the basis of chance alone. It’s more than deserving of deeper consideration by mainstream scholars. If it’s as strong as it appears, I don’t see any other way we would get it other than by an authentic Book of Mormon.

And though they’ve had a firm target on their back since the very beginning, the record of the three and eight witnesses continues to represent an evidentiary bulwark in the book’s favor—not necessarily because of their initial testimonies, but because of their failure to recant those testimonies given more than sufficient opportunity and motivation. None of the popular explanations that try to account for the witnesses change that calculus, whether it be conspiracy or hypnotism or manufactured plates.

From what I can tell, all of these pieces of evidence are stronger, often by many orders of magnitude, than any evidence the critical side of the equation has to offer. If we had to draw a conclusion based on this evidence (and that’s what we’re here to do, after all), it would be that the Book of Mormon is not a nineteenth-century fabrication, but is most probably an authentic ancient text, with an origin as claimed by Joseph and by the book itself.

But that doesn’t mean that the negative evidence has nothing to teach us. Even with an authentic Book of Mormon that evidence is still evidence (except when it’s merely the lack of evidence), and we should be willing to learn from it. Often the negative evidence serves to better hone our expectations and assumptions—to give us a better sense of the nature of revelation and divinely-inspired translation.

For instance, evidence from the Book of Abraham, though still (in my opinion) pointing toward authenticity, suggests that idealized representations of Joseph’s revelatory process—where he can look at ancient hieroglyphics and receive immediate and complete knowledge of what they represent—just can’t be sustained. No matter what version of that process one prefers, Joseph was likely incorrect about a number of aspects of his interpretations, whether it be the location of the Book of Abraham text, the meaning of Egyptian symbols, or the purportedly Egyptian glosses he provides. What the evidence suggests to me is that, when it comes to the facsimiles, Joseph received authentic but incomplete revelatory concepts that he didn’t fully grasp, filling in many of the gaps with his own imperfect understanding.

In a similar vein, evidence gleaned from the Book of Mormon’s quotations from the King James Bible, including the Isaiah variants, the evidence we have of the book’s Early Modern English syntax and lexis, and perhaps even the book’s more modern theological underpinnings, all point to a much more complex translation history than has been traditionally imagined. The image of Joseph forming his own translation of the text from revealed ideas implanted in his head—or of God presenting Joseph with a metaphysically perfect English rendering of the text on the gold plates—should be banished from our minds forever. Joseph, both in this case as well as with the books of Moses and Abraham, seems to be functioning as a “translator” only in the sense that he’s ‘conveying’ the text (which also happens to be the primary meaning of the word translate in 1828), and we’ll likely never know what happened to the text as it made its way from the gold plates to the seer stone. I also find it unlikely that Nephi’s Isaiah chapters represent a faithful word-for-word copy of what was on the Brass Plates—I think further consideration should be given to the idea that Nephi engaged in rather extensive editorializing to further his rhetorical ends.

Together, this evidence seems to leave us with a more nuanced view of a nevertheless-authentic Book of Mormon, one that more than clears the stringent bar of 1 in 1040 odds that we set at the beginning of this statistical adventure. That leaves us, and our skeptic, with an important question, one that we haven’t really tackled up to this point:

So what?

Answering the “so what?” question. There are a couple different “so what” questions we need to answer here. The first is the “why should I care what some uncredentialed dude thinks about the Book of Mormon?” question, and though I’m tempted to respond with “I dunno, why do you care what Jeremy Runnels thinks?”, the question remains a fair one. I certainly think that I’ve hit on some strong arguments and insightful analyses, otherwise you wouldn’t be reading this. Ultimately, though, all of this is just my subjective take on the evidence, and no one should think themselves beholden to it.

What I think is more important than my own judgment, though, is the method. These episodes have been a proof of concept for a Bayesian-based approach to considering and weighing the available evidence. And though the details haven’t all been worked out yet, I’m even more convinced than I was at the start that this is a solid method for doing so. I definitely see it as preferrable to sitting back and watching competing experts duke things out in the court of public opinion, or waiting for some nebulous ‘academic consensus’ to do my thinking for me. And, importantly, the Bayesian approach allowed my thinking to be laid bare—right or wrong, my arguments, my data, and my assumptions are clear. They’re certainly clear enough to allow them to be argued against effectively. (A fact I may now be regretting depending on how things have gone in the comments section.)

But if I haven’t established the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, what have I done? My hope is that what I’ve done is establish something like the following:

- The foregoing analyses represent a reasonable view of the evidence surrounding Book of Mormon authenticity, one that incorporates and fairly portrays the arguments against that position.

- If one takes that view of the evidence, it’s reasonable to conclude that the Book of Mormon is an authentic ancient document, and was not written by Joseph Smith or any of his contemporaries.

- If one believes the Book of Mormon to be an ancient document, it’s reasonable to assume that we received it in the way Joseph said we received it—through the power of a real God, who intervenes actively in human affairs.

If that’s the case, that would mean something rather startling: that the Book of Mormon and the evidence pertaining to it helps make belief in God reasonable. And based on the strength of our conclusions, it might do so more than any other single artifact or any other established historical fact, placing it in such esteemed statistical company as the arguments for universal fine tuning and the improbability of life arising from base chemicals. What’s more, it places that God squarely in a Judeo-Christian and Christ-centered framework. If its Christian critics weren’t so busy trying to tear it apart, the Book of Mormon could be one of the most powerful and valuable evidentiary weapons in Christendom.

I think the critics know this, deep down. It’s why secular forces have done their sustained and level best to summarily dismiss the book and cut it off at its knees. It’s why anyone leaving the Church needs, in the insightful parlance of Jeffrey R. Holland, to crawl “over or under or around the Book of Mormon” on their way out.

But even if it helps make belief in God reasonable, there are a number of things authenticity itself doesn’t do. These include:

- Establish the correctness of the doctrines presented in the Book of Mormon (or, for that matter, in the Old and New Testaments).

- Indicate that Joseph retained divine favor following the publication of the Book of Mormon.

- Establish the authenticity of the Pearl of Great Price or the Doctrine and Covenants.

- Establish the theology of the temple or baptism for the dead or polygamy or the Word of Wisdom or anything else that came through later revelation.

- Validate visions or revelations reported by other Church leaders.

- Validate the divine callings of prophets ordained after Joseph.

- Establish the correctness of Church policies, from the United Order on down to baptizing (or not baptizing) the children of gay couples.

- Give me a compelling reason to pay my tithing, watch General Conference, be active in Church callings, qualify for a temple recommend, look up my family history, stay married to my wife, abstain from pornography, or sit through Church while my four-year-old climbs on my face.

In short, there’s no bright line of logic or evidence from an authentic Book of Mormon to almost anything relevant to living the life of a modern Latter-Day Saint. If we’re going to get there, we’re going to have to go beyond archaeology and linguistics and statistics. Which brings us to our second, and more pertinent, “so what” question: “What would an authentic Book of Mormon actually mean for how I should live my life?”

For some people, the honest answer is "not much." I ran into a surprising number of people on my mission who readily believed the Book of Mormon to be inspired and authentic but who were perfectly content to do nothing about it. And belief in the truth of the book itself has done little for countless people raised in the Church and who retain nominal belief but who’ve nonetheless faded away into inactivity and apathy. Authenticity alone is clearly not sufficient to generate or sustain faith.

And that’s probably because belief—in the sense of assenting to a given proposition—is not faith. I can believe that the earth is round without ever needing to use that fact to guide my life and behavior, and I can believe in the Book of Mormon without actually needing to place my trust in its content or its implications. And I never will unless I have a reason to.

And what are those reasons? There are lots of them. Many of them have nothing to do with truth claims—like wanting to please a family member or to live the way other apparently successful people are living—but some of them very much hinge on taking the truth claims of the church seriously. I think Moroni’s exhortations get at some of the most important ones: wanting to obtain and understand God’s mercy in an otherwise brutal and unforgiving world; wanting to grasp and access eternal truths in a world where truth seems elusive and illusory; or wanting to overcome the fallen nature that you see in yourself, your society, your culture, or your species. Most everything we believe in in the Church is connected to those basic concepts—wanting to believe in eternal families; in redemption for the dead; in the Atonement; in the Resurrection; in prayer; in the promises of tithing, of fasting, of clean living, of chastity. These are things worth believing in, reasons to live a life of devotion and discipleship.

Caring about these things has led untold millions to seek truth in religion, and to keep believing even in the absence of empirical evidence. Not caring about them, on the other hand—or believing them to be impossible, or, further still, fulfilling them through secular means—reduces religion to empty ritual.

Our skeptic—despite himself, despite personal tragedy, despite feeling betrayed by his own faith—still cares about the things religion can bring to the table. He hopes for a better, more merciful, more just universe, where humanity is a seed for something better, something divine. His faith crisis temporarily closed the door on that hope, choking out the root of his previous discipleship. What the Book of Mormon evidence did for him, and what I think it could do for many others, is to crack the door back open, to let people dare to hope in God, in Christ, in authentic scripture, in inspired leadership, in the influence of the Spirit. Not everyone’s going to walk through that door. But once they can see a bit of light on the other side of the frame, the book and the Church and the Spirit can give them reason enough to do so, especially if they can hear Christ knocking from the other side.

All those things in the list above—the things that the Book of Mormon doesn’t do—are in my mind much more matters of faith than the Book of Mormon itself. All of them can be informed to a certain extent by evidence, but for the most part the only way to know their validity is through experience, through applying the test of Alma 32, through hoping enough in the value of commandments and scripture and true prophets and the Holy Ghost to test out what they have to say. That experience is destined to be far from perfect. But for those who find their lives improving as a result—who experience the many tangible and established benefits of a religious (and particularly an LDS) lifestyle—that imperfection doesn’t detract from the overall conclusion: that living the gospel has value, independent of and yet because of its divine origins, and that the choice to live it has the potential to reverberate into the eternities. The possibility of making that discovery is as good of a “so what” as I could hope to extract from an authentic Book of Mormon.

Conclusion

This episode was supposed to be about conclusions, but the point of this has always been that there aren’t any—that there’s always room for further investigation, that conclusions are necessarily tentative, and that answers will never be final. The question we should ask ourselves now isn’t, “is the Book of Mormon authentic?” We could instead ask two other questions: “is there enough evidence for me to hope?” and “do I have enough hope to exercise faith?” I can’t answer either of those questions for you, and, as you’ll see, I can’t answer them for my skeptic either. I can only answer them for myself. My answer to the first, based on my analyses here, has to be a clear and emphatic “yes.” The answer to the second can be found in how I live my life: I read the Book of Mormon; I pray to a God who I believe hears and answers me; I do my best to serve (badly) in my Elders Quorum; I go to Church and do my best to fight sleep and boredom and the antics of inattentive children; I pay my tithing; I teach my children to live and obey and believe in the gospel and in the Church and in the authentic stories of scripture; and I take seriously the imperfect counsel of my imperfect leaders.

Too often we treat Moroni 10:3-5 as a simplistic formula for getting a one-time answer to the specific question of Book of Mormon authenticity. We pray; we ask; we feel; we get baptized. I don’t argue against receiving meaningful, immediate, and powerful answers to those sorts of prayers—I’ve seen them and experienced them firsthand. But the promise of those verses is so much broader than we generally give it credit for. Moroni doesn’t specify when or in what way or even what truths will be made manifest to us. All he says is “these things.” I see those things as applying to the message of the book itself more so than its authenticity. He lays that message out in the rest of his exhortations: the existence of a merciful God, whose gifts are accessible to those who seek for them, and how, through them and through Christ, we can seek to be made whole.

Authenticity is but the spark that helps ignite and sustain hope in those things. It’s up to us to live them, and to see the truth of them manifest in our own lives. How we do so effectively is likely to be a much more fruitful target of inquiry—for ourselves, for our relationships, for our children, and for our societies—than picking up Egyptian or learning the ins and outs of Early Modern English. Questions of authenticity will continue to ebb and flow, as will the evidence that supports or refutes them. But the answers to those questions won’t save us; they have no salvific value. All they can do is start us—or keep us, or return us—on the path back home.

The Epilogue

You don’t have to wait long before the door to the inn opens, its creaking hinges bringing your train of thought to a screeching halt. Through it comes the young man, weariness more than evident on his face. It takes him a few seconds to catch sight of you. When he does, the weariness fades almost instantly. You, it seems, are a sight for his sore eyes.

“Greetings, good sir!” he says, with as much enthusiasm as he can muster. “I’ll admit to thinking that I might not see you again.”

You smile quizzically. “Weren’t you supposed to come see me before you left?”

He laughs somewhat sheepishly. “That was the plan, though given the number of doors I’ve knocked on this week, knocking is no guarantee that you were going to open up.”

You stop and think for a moment just how difficult this boy’s task was. Even if he thought his calling to be inspired, you knew first-hand the mean spirits of some of the people in this town—facing their ire was daunting enough under normal circumstances. To do so while challenging their most deeply held beliefs would take its toll.

“But if you’re here,” he said, “I’m assuming you read the book.”

He looks at you expectantly, and you nod slowly, choosing your words carefully. “The book you gave me is certainly a strange one. I found much to recommend it and a few things I’m less sure about. I don’t know what to make of it, frankly.”

He moves to sit down in the chair next to you. “I’m not sure making something of it is the point.” His hand moves up, his finger pointing forward. It looks like he’s going to point to your head at first, but the finger ends up going to your heart. “The point is to learn something from it. What was it that God had to teach you?”

Your mind goes not to the words of the book or of the hours you spent contemplating its strengths and weaknesses. It instead goes to what you felt, to the feeling of the words moving through you from the centuries past, to your dreams—of being buffeted by volcanic smoke, and of the book being strengthened through repeated abuse. Your mind remembers the internal plea you’d uttered only moments before, the gnawing hole you felt inside that almost screamed to be filled.

You also feel hesitation, anxiety, and uncertainty. You’re not certain what had happened the last few days, but you’re even less certain about what might happen now, or tomorrow, or ten years hence. You find yourself standing up and reaching into your pocket, where you find a silver dollar. “I learned,” you say, handing him the dollar, “that I still have much to learn.”

You walk to the same door that he had just come through. “Feel free to call on me again,” you say, though the young man still seems to be staring at the dollar in his palm. “But you have to promise not to be surprised when I open the door.”

You turn and walk toward your wagon, allowing the creak of the door to see you out.

Next Time, in Episode 24:

There is no next time. In fact, there is no episode 24. You’re done! Go do something productive with your life!

Questions, ideas, and parting curses can be left to stew in the cauldron of BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

| Evidence | Evidence Score | Evidence Summary | Key Estimates | A Fortiori Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (P) Early Modern English | 20 | Early Modern English syntactic features occur much more frequently in the Book of Mormon than they do in other pseudobiblical texts. The Book of Mormon contains a substantial number of word meanings only used in the Early Modern period. | 74% of featured syntactic examples in the Book of Mormon are archaic, vs. 23% in the King James Bible and 6% in pseudobiblical texts. Probability of observing this, after making an extremely conservative adjustment, would be p = 8.24 x 10-13. If the average number of archaic lexis in nineteenth-century texts is 1, the probability of observing half of the 26 identified archaic examples (based on a Poisson distribution) would be p = 6.36 x 10-11. | Assuming that there are five times the number of syntactic features that don’t point to EModE, and that half of the identified lexical examples are spurious. Estimate for the average number of archaic lexis in modern texts is likely too high. |

| (P) Trajectory | 20 | At least 70% of all the Book of Mormon anachronisms identified by critics have been overturned by new evidence aligning with Book of Mormon claims. | If theories of Book of Mormon geography still centered in the Northeast and Central U.S. (an “original assumptions” theory), the proportion of confirmed anachronisms would be around 24%, or 38% if Old World anachronisms are included. If that matches what we’d expect from a fraud, probability of observing 70% would be 5.29 x 10-23, based on simulated data. | Does not include anachronisms that have been trending toward confirmation. Incorporates Old-World confirmations into the original assumptions estimate. |

| (P) Chiasmus | 14 | There are beautiful, meaningful, and frequently occurring chiastic and parallelistic poetic structures in the Book of Mormon. These structures are not distributed randomly or evenly throughout the text, but differ based on narrative context. | Using the Text-to-Token Ratio (TTR) as a proxy for the frequency of repetitive poetic structures, the Book of Mormon greatly exceeds what we would expect from a pseudobiblical text and aligns with that observed in the Bible, with an estimated probability of observing Book of Mormon TTRs at 3.14 x 10-10 if it was a modern text. Significant differences between the frequency of chiasmus in sermons vs. letters is reported at p = 1.6 x 10-5. | Does not take into account the potential complexity of individual chiasms, such as Alma 36. |

| (P) Uto-Aztecan | 14 | The Uto-Aztecan language family shows a substantial (1528) number of correspondences with Egyptian and Hebrew, the languages that would have been spoken in the Book of Mormon. | An estimated 3% chance that an Uto-Aztecan word would match a word in an unrelated language, based on the quality of correspondences recorded by Stubbs (8.7% to find at least one match in the three independent near-eastern language forms), which would correspond to an estimated 235 spurious matches for the 2700 words in PUA. Counting only correspondences for words in PUA, with exact matches in meaning, and assuming a 20% error rate, we estimate a core correspondence set of 422 exact matches in PUA. Probability of finding 422 if the average is 235 would be p = 6.99 x 10-15. | Assumes independence of Egyptian, Semitic-p, and Semitic-kw. Does not incorporate non-exact meaning matches. Does not incorporate the idea that Stubbs’ correspondences solve longstanding problems faced by UA linguists. |

| (P) Witnesses | 8 | The three and the eight witnesses to the Book of Mormon maintained their testimonies in spite of severe persecution and personal animus against Joseph Smith. | If, independent of other factors, 10% of those not part of Joseph’s family, 50% of those threatened with death, and 90% of those who turned against Joseph would have recanted their testimonies, the estimated probability of none recanting would be p = 2.69 x 10-8. At an estimated 930 hours of work to produce a convincing set of plates (480 hours to hammer out 20 plates, 450 hours to engrave 30,000 characters), and a 1% risk of getting caught per hour, the probability of escaping detection would be p = 8.72 x 10-5. The probability of getting all three of the three witnesses to accept a strong hypnotic suggestion (10% chance of being highly susceptible to suggestion, and a 75% chance of accepting a difficult suggestion) would be p = 4.2 x 10-4. | Conservative estimates of recanting under each condition. High-end assumptions of engraving and metallurgy speeds. |

| (N) Book of Abraham | -8 | Modern interpretations of the facsimiles and hieroglyphics do not match those produced by Joseph. | After collating and evaluating the negative evidence, I count 3 pieces of evidence at the .02 (50) level, 4 at the .1 (10) level, and 6 at the .5 (2) level, for a total p = 1.25 x 10-11. After collating all the positive evidence, I count 2 at the .02 level, 9 at the .1 level, and none at the .5 level, for a total p = 4 x 10-13. If all the positive evidence is adjusted to be at the .5 level, the estimate on the positive side is instead p = 4.88 x 10-4. | Provides an extremely conservative adjustment applying the weakest weight (.5) to all positive evidence. |

| (P) Dictation | 5 | Based on eyewitness testimony to the dictation process, the Book of Mormon manuscript was dictated in a very brief period of time with little if any direct evidence of in-line revision or repair and without reliance on notes. Joseph reportedly was able to begin dictation without being prompted as to where he left off. | Based on modern estimates of repair and revision during dictation (3.37 changes per 150 words; SD = 0.5), and counts of potential changes by scribes in the original manuscript (1.68 changes per 150 words), the probability that Joseph authored the book while dictating would be p = 7.25 x 10-4. At an estimated 356 hours of work to write and memorize the manuscript prior to dictation (at an estimated composition pace of 750 words/hour), and a 1% risk of getting caught per hour, the probability of escaping detection would be p = .0297. Using results on a commonly used psychological memory test (4.63 out of 10, SD = 1.48), and assuming being able to begin dictation without prompting would be as or more difficult than a perfect score on that test, the probability that Joseph could do so would be 2.83 x 10-4. | Liberal estimates of speaking and composition rates. Assumes all scribal changes to the original manuscript are in-line repairs or revisions made by Joseph. |

| (P) Stylometry | 5 | Stylometric analyses indicate the presence of multiple authors in the Book of Mormon text, none of which closely matching Joseph or any other nineteenth-century candidate. | If you assume Joseph shouldn’t be ranked among the nineteenth-century’s best literary minds, the probability of observing the results in the Hilton study by chance would be p = 1.42 x 10-16. If you assume that he belongs in that prestigious group, the probability of observing the results of the Roper study is estimated at p = 2.0 x 10-5. | Assumes that the results of the Hilton study could be reproduced by someone as talented as Faulkner based on differences in characterization. |

| (N) Modern Themes | -5 | Faithful and critical scholars have each amassed a variety of evidence pointing to both ancient and modern authorship. | After collating and evaluating the negative evidence, I count 8 pieces of evidence at the .02 level, 8 at the .1 level, and 2 at the .5 level, for a total p = 6.4 x 10-23. After collating all the positive evidence, I count 6 at the .02 (50) level, 7 at the .1 (10) level, and none at the .5 (2) level, for a total p = 6.4 x 10-18. | Conducting a less thorough review of positive evidence than for negative evidence. |

| (N) King James Variants | -4 | Many of the differences between the Isaiah chapters in the Book of Mormon and the King James are centered around italicized words, retain King James translation errors, seem ignorant of the Hebrew of the Masoretic, and seem like secondary expansions to the text. | Based on comparing paraphrased to translated biblical texts, the rate of positive variation matches with the Masoretic identified by Tvedtnes (6%) could be reproduced via a paraphrasing process (6% hits) with an estimated p = .46. The Book of Mormon’s treatment of italicized words does not exceed that of non-KJV-based translations of the Bible (40 changes between the NIV and KJV in Isaiah 2-3, vs. 36 for the Book of Mormon). Non-italics variants are not statistically more likely to occur in verses with italicized words (33%) than without (28%), p = .63. | Adjusting the consequent by four orders of magnitude without available statistical justification for doing so. |

| (N) Archaeology | -4 | There are a number of valid questions around missing archaeological evidence for Book of Mormon peoples, though there are many correspondences between Mesoamerican and Nephite/Lamanite culture, politics, and geography that can be difficult to explain. | After collating and evaluating the negative evidence, I count 8 pieces of evidence at the .02 (50) level, 3 at the .1 (10) level, and 7 at the .5 (2) level, for a total p = 2 x 10-19. After collating all the positive evidence, I count 16 at the .02 level, 14 at the .1 level, and 18 at the .5 level, for a total p = 2.5 x 10-47. If all the positive evidence is adjusted to be at the .5 level, the estimate on the positive side is instead p = 3.55 x 10-14. | Provides an extremely conservative adjustment applying the weakest weight (.5) to all positive evidence. |

| (P) Consistent Geography | 4 | The Book of Mormon presents a complex geography that demonstrates an impressive amount of internal consistency, particularly if it was dictated in its entirety without notes. | I counted and mapped 151 unique geographic relationships between locations in the book. Based on a study where individuals had to recall a number of generated ideas (with an 18% error rate; SD = 4.3%), we would expect 28 consistency errors to have arisen in those relationships. The probability of making only two errors given that assumed distribution would be p = 7.9 x 10-5. | Not included due to lack of independence. Conservative estimate of the number of opportunities to make a consistency error. Uses the lowest observed error rate in the comparable psychological study. |

| (P) Onomasticon | 4 | Many of the personal and place names in the Book of Mormon have plausible etymologies in ancient Egyptian, Hebrew, and other near-eastern languages, and these meanings often form interesting wordplays. Jaredite names differ substantively and systematically from other names in the text. | Based on the etymologies available in the Book of Mormon Onomasticon, Jaredite names are significantly more likely to have no available near-eastern etymology than Lehite names (28% vs. 6%) and are less likely to connect to Hebrew or Egyptian, at p = 2.32 x 10-4. A study by Wilcox showed that Jaredite names substantially differed on a number of linguistic measures (relative to Tolkien names) with significance at least below the p = .05 level. Names with a valid wordplay had a significantly higher number of potential meanings associated with them in the Onomasticon than those without (3.23 vs. 2.19, p = 8 x 10-4. As random associations with Spanish words produced 10 potential wordplays, the probability of producing the observed 43, given an average 2.47 associated meanings for each word, would be p = .008. | Does not incorporate consistency with ancient naming norms. Assumes the minimum probability level for linguistic differences in the Wilcox study. |

| (P) Page Count | 3 | The page count of the Book of Mormon exceeds what one would expect from a first-time novelist, particularly one so young and so poorly educated. | At about 306 words per page, the Book of Mormon would take up about 876 pages in normal print. Joseph had 7 (spotty) years of education and was 24 when the Book of Mormon was published. In comparison with 100 first-time authors of famous works in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century, the probability of someone like him producing a work of that length is estimated at p = 6 x 10-4. | Used conservative education estimates for those with missing information or who were privately tutored. Does not incorporate the distribution of work across the lifespan. |

| (N) DNA | -3 | Evidence of Middle Eastern DNA from the appropriate time period has not yet been found in North America. | The statistical power of large-scale autosomal DNA studies suggests that the probability of having missed a major migration is at least p = .06. The opinion of a variety of experts on the likelihood of sex-linked DNA not surviving suggests it would be possible for Lehi’s to have done so, with that probability estimated at p = .02. | The power for detecting Lehi’s minor genetic contribution would have been much less than average. Likely a conservative estimate for sex-linked DNA not surviving. |

| (P) Nahom | 2 | Archaeological evidence for a place called NHM has been found in the right spot and time period claimed for the location in the Book of Mormon. | Given the distribution of the number of consonants in Book of Mormon names, and a 200km range for a potential eastward turn in southwest Arabia, I estimate 92 potential place names that could have been identified as valid locations for Nahom, with the probability of a Book of Mormon name randomly matching at least one of those sites at p = .0097. Rough probability for Joseph obtaining the name from a map is estimated at 1.56 x 10-4. | Does not incorporate other evidence related to Lehi’s trail, or the likelihood of the name also having a meaningful wordplay. |

| (N) Transoceanic | -2 | It would have been difficult for Nephi and his family to build a boat and then survive the journey to the New World. | Using estimates that Viking longships could take 28,000 hours to build (with a capacity of 80), I extrapolate that Nephi’s boat (carrying 40) could have taken around 16,500 hours to complete (with an estimated SD = 1,000 hours), assuming a portion of time (~5,000 hours) was spent prepping and building tools. Assuming two years, 200 working days per year, 8-hour days, and 5 individuals laboring, I estimate that Nephi would have had at least 16,000 hours of labor available to him, with an estimated probability that this would have been sufficient for his boat at p = .3085. Based on amateur voyages of makeshift boats in the Pacific, I estimate the risk per mile of that type of ocean voyage at .0001. If that risk is doubled, the likelihood of Nephi and his family surviving the 17,000-mile voyage would be p = .0265. | Nephi’s boat could have been much simpler and easier to build than a Viking longship. Conservative estimates for working days and number of available workers. Doubled the estimated risk/mile for ocean voyages. |

| (N) Imperfect Prophets | -2 | Modern prophets make mistakes. | Modern prophets appear to make a similar class of mistakes as the prophetic figures of the Old and New Testament, who, at my best guess, appear to make mistakes that are 0.5 standard deviations less severe than the average non-inspired person. Even if all modern and Book of Mormon prophets (29, by my count) were as fallible as the average non-inspired person, the probability that they would still fall in the same distribution as prophetic figures would be p = .00522. | Assumes that all modern and Book of Mormon prophets are as fallible as the average non-inspired person, despite reason to believe that they are generally above average in that regard. |

| (N) First Vision | -1 | Joseph’s four firsthand accounts of the First Vision show a number of inconsistencies and contradictions. | Based on an analysis of the details in the First Vision accounts (and not including details unique to the lengthier 1842 account), I observe that the First Vision accounts are 30% consistent and show four key contradictions. Nevertheless, available research indicates that true accounts are not much more consistent than fraudulent ones (a difference of 0.84 standard deviations). Given an observed average consistency rate of 67% (SD = 12.8%) the probability that the First Vision falls into the distribution of true accounts would be p = .003, and the probability for false accounts would be .035. | Estimates of average consistency and differences in consistency are for accounts that are given at a much closer span of time than the First Vision accounts–a wider variety of accounts would likely produce an average that’s less consistent, and their greater variability would probably water down the difference between truth and error. |

| (N) Plagiarism | -1 | The Book of Mormon shows a number of correspondences between books such as The Late War and View of the Hebrews. | If the Book of Mormon had been set on almost any continent on the planet (minus Antarctica), it would have shown similarities with claims of the lost ten tribes in various regions around the world, similar to its connections with View of the Hebrews, with an estimated probability of p = 6/7 or .857. The connections to The Late War are, in reality, only 1/5th as strong as the strongest “influence” on Jane Austen, which we know did not strongly influence her. I note 14 potentially interesting conceptual parallels between The Late War and the Book of Mormon, while Jeff Lindsay found at least 10 from the Leaves of Grass (written after the Book of Mormon). Assuming a standard deviation of 5, this would put the probability of observing 14 in two unrelated books at p = .21. | Uses Jeff Linday’s analysis of Leaves of Grass as a comparison–Lindsay didn’t comb through hundreds of thousands of texts to find the one that was the closest match, as was done with The Late War. |

| (N) Politics | 0 | At times the Book of Mormon and the modern church run afoul of its members’ and the wider society’s political sensibilities. | Based on my own analytic induction analysis, I observe seven different general categories of political ideas. Based on a study that uses general political orientation to predict specific political stances, the best we can get at predicting one political stance using another is 88.9%. Using that as an upper bound, the probability that you would disagree with someone (including God) on at least one of those areas would be at least p = .56, even if you’re generally on the same side of the political aisle. | Assumes all political disagreements with the book result from God’s own beliefs rather than fallible modern or ancient prophets. |

| (N) Place-Name Plagiarism | 0 | Some Book of Mormon place names bear (minor) resemblance to some place names in a (quite large) region around Palmyra. | I was able to generate a comparable list of similar place names using a set of names from Wisconsin, Florida, Minnesota, and Missouri, which have an area comparable to that covered by Holley’s list (663,954km |

Used a list that had only incorporated municipalities. It would’ve been possible to use a list of unincorporated places that was about 5 times larger. |

Will the essays be updated to include new scholarly information that comes out or has already come out since the essays got completed?

It’d be hard to keep these truly current (and even harder to keep the math lined up across the entire series, since the changes would compound). If there was something that I thought dramatically altered my conclusion in any of these areas I’d certainly consider adding an addendum. Stubbs brought forward a few additional implications that I’d missed in my Uto-Aztecan essay that would certainly fit the bill–if he fleshes out those arguments further that would be the sort of thing worth a clarification.

Thanks Jeremy!

In a fitting conclusion, Kyler Rasmussen demonstrates the why’s and wherefore’s of his understanding of what the Book of Mormon actually represents; for himself, for the Church and its members, and for humanity.

It seems apparent, that just like the young Joseph Smith, Kyler has delivered a work that can be weighed on its own evidentiary self, or can be weighed by examining what you feel in your heart after reading it.

I think this has been a fitting series of articles, completely worth the endeavor. Throughout the series, my complaints have been that the analysis has always leaned overbearingly onto the side of the arguments of the detractors, but Kyler shows exactly why this had to be so.

Great series, Kyler Rasmussen! I especially love your concluding remarks!

Overall these Bayesian analyses were pretty interesting, though I will point out that the entry on Nahom excludes the evidence about an Ishmael being buried near there.

https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/an-ishmael-buried-near-nahom/

Of course that’s not to say that that Ishmael is definitively the same Ishmael as the Ishmael in The Book of Mormon, but it is still evidence nonetheless and so should be at least mentioned, even if not factored into the analysis.

Thanks Jeremy. The Ishmael article is definitely worth bringing up in the context of Nahom. It’s too bad Rappleye’s article was published several months after my Nahom essay was already posted. It’s hard to keep things current!

Kyler – I am a student of the Book of Mormon, not a scholar, but I have studied it through different “lenses”, some of which you touched upon. Nor would I pretend to be a statistician for that matter, but I have an appreciation for your use of statistics. Your approach and that of many who have examined different aspects of the Book of Mormon over many decades, reminds me of the different types of telescopes that can zoom in on the same galaxy. Yet they see such different features – but when you collect all of the images and composite them into a single image, its beauty is breathtaking. As technology gradually improves and new telescopes are launched, strange new features pop into view, and the picture becomes ever more stunning (and complex).

I collected enough evidence years ago to convince me of the reality of the Book of Mormon, yet I continue to peer through other telescopes that focus on its different aspects, illuminating new and exciting features. No single one of them proves anything, but taken together (as you point out so well), there is but one inescapable conclusion….. at least for me. I was a new convert of 6 months before I read the Book of Mormon from cover to cover, and from that first experience I gradually, quietly came to “know” that it had divine roots. And now (more than 50 years later), I am more convinced than ever. Thank you for your carefully considered and thoughtful analysis, and the courage to present the counter argument. Your enthusiasm and honesty are much appreciated!

Good insights, Mike. Thanks for reading.

Excellent series! I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Your conclusion reminds me of my mission. We ran into a Jehovah’s Witness. I am sure I was sent to that area because at the time I likely was one of the few missionaries in my mission who even knew what the Book of Ecclesiastics was, and had read a large chunk of the Old Testament.

Thus, I was able to answer her questions. But interestingly, I didn’t resolve them. I provided a plausible explanation. And when we returned the next day for our next lesson, it turned out that the Spirit had convinced her overnight. My job, apparently, was to open the door to belief–and let the Spirit do the real work. Much like your essays here.

And why not? Even seeing an angel did not permanently fix Laman and Lemuel, after all. True conversion only comes through the Spirit and consistent devotion afterwards.

Once again, fascinating series and thank you for the essays!

Thanks Vance!

You have provided an extremely interesting and important basket of ideas that will challenge both the novice and the specialist for years to come. Congratulations and thanks for impressing a very difficult person to impress.

David L Clark, dlclark15@gmail.com

Thanks David. If even a small fraction of that comes to pass I’ll be very pleased.