[Page 71]Abstract: People leave the Church for a variety of reasons. Of all the reasons why people leave, one that has attracted little or no attention is the influence of mental distress. People who experience anxiety or depression see things differently than those who do not. Recognizing that people with mental distress have a different experience with church than others may help us to make adjustments that can prevent some amount of disaffection from the Church. This article takes a first step in identifying ways that mental distress can affect church activity and in presenting some of the things that individuals, friends, family members and Church leaders can do to help make being a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints a little easier for those who experience mental distress.

[Editor’s Note: This paper was presented at the 2018 FairMormon Conference in Provo, Utah, August 2, 2018.1 To prepare it for publication, it has been source checked and copy edited; otherwise it appears here as first presented.]

We probably all know people who have left the Church. Often, people become involved in apologetics because they want to help convince their friends or family members who have left the Church to come back. Or they want to understand why the friend or family member left. Or they want to help prevent others from leaving.

[Page 72]About 25 years ago, one of my best friends left the Church. I have struggled to understand why this young man, who was raised in the Church, had served a mission and was married in the temple, later left the Church. Other close friends, extended family members, and immediate family members have also left the Church. As a result I have thought a lot about why. I have had conversations with people who have left, I have studied perhaps hundreds of stories that have been shared online, and I have examined survey results and scientific literature to gain some understanding of their perspectives. Along the way, I’ve also met with many therapists and researchers. Dr. Geret Giles is one of those, and I’m grateful for his willingness to join me in making this presentation.

We would like now to share some observations with you, and I hope that this kind of discussion will help all of us to be better shepherds. We have come to understand that many factors contribute to disaffection from the Church. I’ll begin with a general discussion of this topic, but we will then focus on mental distress as one of the many factors that can contribute to disaffection from the Church. And when we say “mental or emotional distress,” we intend to include not only mental illness but also distress that perhaps falls short of meeting all the criteria for a clinical diagnosis. Mental and emotional distress can impact all of us even if we are not actually diagnosed with mental illness. And while mental distress is not the only factor (and perhaps not even the predominant factor), it is worth examining and understanding the role it may play in the development of a faith crisis as we seek to lift one another’s burdens.

Disaffection from the Church is not new. Before we even came to this world, a third part of the host of Heaven turned away from God (Revelation 12:4; D&C 29:36). We can read throughout the scriptures stories of the children of “goodly parents” who denied their faith. But the reasons are not always clear.

In more recent times, we have all been aware of those among us who have drifted away. Growing up, I had relatives and neighbors who simply appeared to have lost interest in religion and just became more interested in doing other things on Sunday. We may have attributed their disaffection to the fact that they were offended or that they couldn’t stop smoking or that they really liked the taste of coffee. Or they may have quietly continued attending church — even though they had lost their faith — for fear of becoming social outcasts in a large community of believers.

One thing different today is that there are more ways for people to share their stories of disaffection about the Church than ever before. And [Page 73]the fact that there are new outlets for sharing these stories has perhaps emboldened people to be more open about their loss of faith.

It is not hard now to find a new community on the internet — a community of nonbelievers, a community with whom one can share one’s story of disaffection from the Church and instead of shock, fear and dismay, encounter compassion, understanding, and encouragement. Therefore, in seeking to prevent disaffection from the Church, it is more important now than ever that we extend compassion, understanding, and encouragement to those who express feelings of pain, doubt, and discouragement while they are still in the Church. We must prepare to address the sincere crisis with compassion and truth. After all, if people who are experiencing a faith crisis find more comfort and compassion outside of Christ’s community, we probably are not doing what Jesus would do.

Of course, some of the comfort offered outside the community of believers is false comfort, and we should be clear about that. One thing often said by online critics is that Church membership is in decline and that even Elder Marlin K. Jensen admitted that people are “leaving in droves.” However, it is not true that membership is in decline nor that Elder Jensen said that people are “leaving in droves.”2 In fact, once people started claiming that Elder Jensen had said this, it was reported in the Washington Post that Elder Jensen insisted that critics of the Church were overstating the Mormon exodus over the Church’s history. He was quoted as saying, “To say we are experiencing some Titanic-like wave of apostasy is inaccurate.”3 He is, however, concerned about people encountering troubling information on the internet and leaving the Church.

In the face of growing membership rolls for the Church internationally, critics of the Church claim there is actually a wave of apostasy simply obscured in the Church’s official numbers, since many people leave the Church and do not remove their names from the rolls. However, this speculation is refuted by the data. Attendance at other predominantly white, Christian churches in America is in decline. But researchers have noted that “there is little evidence to suggest that [The [Page 74]Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints is] experiencing similar declines.” 4 While it is true that church growth in the United States has slowed, when Americans are asked what Church they belong to, the same proportion of people, 1.9%, claimed they were Latter day Saints in 2017 as they did in 2011.

It has been reported that Christian millennials in general, not just Latter day Saint millennials, are “leaving in droves.”5 It is therefore significant to note that “Mormons are also much younger than other white Christian religious traditions. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of Mormons are under the age of 30. Fewer than half (41%) are age 50 or older.”6 In light of the fact that our church is younger than other churches and yet is not shrinking like other churches, it seems, as Mark Twain might say, the reports of the death of the Church are greatly exaggerated.

Of course, reports that people are leaving in droves may help those who leave the Church to feel more confident in their decisions, especially as they join online communities. When someone close to you leaves the Church, something shifts. The taboo against leaving diminishes, and the social prohibition that says leaving the Church is something you should not do also fades. Social media amplifies that because more people hear about it. As people feel supported in their decision to leave the Church and emboldened in finding they are not alone, we hear more about why they left. The bright side of this is that it gives us the opportunity to understand and to prepare a wiser, more compassionate, and more effective ministry to those who are struggling.

It can come as a surprise to those who have assumed that people leave only because they were sinning to hear all variety of reasons why people have left. It may also have come as a surprise to hear President Uchtdorf say that “sometimes we assume it is because they have been offended or lazy or sinful. Actually, it is not that simple. In fact, there is not just one reason that applies to the variety of situations.”7 In fact, when the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life asked more than 2,800 Americans why they had decided to join a new church or leave religion [Page 75]behind entirely, “the answers were so varied that analysts nearly ran out of codes to categorize them.”8

Discussions regarding loss of faith among Latter day Saints commonly identify intellectual or social factors such as troubling historical or doctrinal issues9 or social or cultural factors such as not feeling like they belonged among Latter day Saints or simply wanting to do other things with their time.10 So there is not just one reason all people leave. But it is also true that for any one person, probably a complicated variety of factors led to an exit from the Church.

In my personal experience of examining the stories of people who have left the Church, I’ve found that people often point to some incident that ignited a flame under them, creating severe emotional pain. When the flame was not extinguished, it became too difficult to stay in the Church. They may have identified some point of doctrine or episode [Page 76]of history or a policy of the Church. Some have acknowledged being offended by a Church leader or other member. Some have reported that due to shame or guilt, they stayed away and found it difficult to return. And, of course, there are a myriad of other reasons.

Unfortunately, believers can sometimes dismiss the doubter’s pain. For every person who identifies one particular issue that led to his or her exit, there are many others who have encountered the same issue and have decided to stay. Church apologists familiar with the arguments against the Church and the responses to those arguments are sometimes guilty of exclaiming, “They left because of that? That’s just silly!” Every member of the Church has encountered difficult doctrinal or historical issues. All members have been offended or felt like they did not fit in. And every member has sinned (Romans 3:23). So when those of us who stay hear that someone left because of one particular issue, we may find it hard to understand unless it is an issue with which we have also personally struggled. And even then, we may conclude that we stayed, so that person should too.

Of course, some who have left the Church find it difficult to understand how we can stay. They often assume that if we just knew what they knew, if we just watched this movie, or if we read that letter, we wouldn’t stay either. They are surprised to learn that many of us know everything they know but choose to stay anyway. And just as there are a variety of reasons why people leave, there are a variety of reasons why people stay. We hope the reasons we stay may help others see how they, too, can stay. However, because we are always ready to give a reason for the hope within us, we should do so with gentleness and respect (1 Peter 3:15). We should not trivialize, demonize, or dismiss those who choose to leave. We don’t embrace the apostasy, of course, but we should seek to understand and love the lost sheep and, where we can, offer comfort, care, and compassion.

Whether one leaves or stays, a complex set of factors is involved. Once some incident lights a flame of discontent, various other experiences may feed the flame. For example, a person who is disturbed by some item of history or doctrine may begin to find it harder to avoid taking offense at the actions of Church leaders and Church policies. A person who feels overwhelmed by the demands of a religion that calls upon us to become “perfect” (Matthew 5:48) may stumble upon upsetting issues related to Church doctrine or history and feel relieved at the thought that perhaps it isn’t true anyway. A variety of social, historical, doctrinal, spiritual, [Page 77]and intellectual factors combine, so that if a person does not find a way to douse the flame of distress, he or she will feel compelled to escape.

Along with social, historical, doctrinal, spiritual, and intellectual factors, psychology may also play a prominent role in many cases. This concept first dawned on me as I searched for answers to the question of why people leave the Church. As I looked for common factors among those closest to me and among the stories of others who have shared their experiences on the internet, it occurred to me that many who leave the Church comment on the mental illnesses they are also experiencing. As I began to explore the possible connection between mental distress and disaffection from the Church, I found an emerging body of scientific literature that helps explain how depression and anxiety disorders can possibly contribute to disaffection from the Church.

A 2015 survey conducted by Michelle Medeiros, a non-Mormon PhD candidate at Palo Alto University, found that “more religious Mormons were more likely to report lower levels of obsessions and compulsions, and, correspondingly, less religious Mormons were more likely to report higher levels of these traits.” 11 One could say that either OCD is causing a decrease in religiosity, or a decrease in religiosity is causing an increase in OCD. However, because OCD has a strong biological component, it seems more likely that OCD may be causing a decrease in religiosity among Mormons.

Scientists have also observed that “there are major similarities in information processing between anxious and depressed patients. In both groups, maladaptive schemata systematically distort the processes involved in the perception, storage, and retrieval of information.”12 In other words, people with depression and anxiety see things differently and remember things differently.13 It has also been postulated that “‘an anxious patient will be hypersensitive to any aspects of a situation that are potentially harmful but will not respond to its benign or positive aspects.’ There is plentiful evidence that anxious individuals [Page 78]selectively allocate processing resources to threatening rather than to non threatening stimuli.”14 “Non-anxious individuals, if anything, show the opposite kind of bias.”15

To illustrate this point, two friends of mine who are married were burglarized once while they were at church. She is anxious and he is not. It haunts her to remember how he left a side door unlocked, which allowed the burglar to enter their home while they were away. She ruminates on what might have happened if they had surprised the intruder by returning while he was there. Despite his wife’s distress, he still forgets to lock doors. When he is home he doesn’t lock the door to the house or garage, even at night. By contrast, she locks doors whenever possible, including times when she has locked him out of the house while he mowed the lawn. Their psychology results in completely different evaluation of likely threats, even after experiencing the same burglary through an unlocked door.

A substantial body of research that exists demonstrates that anxious people, whether diagnosed with an anxiety disorder or who simply have an anxious disposition, are drawn to threatening information, tend to dwell on threatening information longer than others, and tend to interpret information in a threatening way when the information is ambiguous.16 Whether they [Page 79]experience a social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder, they have a harder time ignoring information they perceive as threatening.17

When the future is unclear, people who experience anxiety and depression tend to expect the negative and tend to expect the results to be more costly when compared to those who are not anxious or depressed.18

This research makes it easier to understand how two people can encounter the same information and respond to it in very different ways. Consider how this may play out when encountering information regarding Church history, policies, doctrine, or ambiguous social situations. An anxious person will tend to focus on the threatening information and will tend to think about it longer, and when it is open to multiple interpretations, an anxious person will tend to interpret it in a more threatening way. If you are generally more likely to identify a situation as threatening and more likely to expect the results of the issue to be devastating, your experience with challenging issues at Church is more likely to be painful and hard to ignore or dismiss.

For many of us, when we encounter Church history or doctrine that is upsetting or hard to understand, we find some relief in “putting it on the shelf.” We stop thinking about it and perhaps come back to it later when we have more information. However, those who are anxious or depressed seem to experience difficulties in ignoring or forgetting negative information.19 It is more difficult for them to divert their attention from threatening information.20 Many people cannot just “put things on the shelf” and forget about them. Instead, issues they find threatening just keep piling up but do not easily leave the forefront of their minds. In light of this, it is interesting to note that many ex-Latter day Saints talk about how, after putting so many things “on the shelf,” their shelf finally broke. It is therefore important to ask how we might help unburden a loaded [Page 80]shelf before it breaks, strengthen the shelf, or repair a broken shelf and clean up the shattered mess beneath it.

In many instances you don’t need a scientific study to tell that depression and anxiety can reduce Church activity. If someone is lying in bed for most of the day due to depression, that probably explains why he or she is not coming to Church on Sunday morning. We may wrongly assume such people have been offended or have lost their faith for some reason, without considering that those persons may need to be treated for depression. In the past, some bishops have maybe even felt reluctant to refer someone to a psychologist. However, the Church now provides bishops with resources to address mental illness, and lds. org21 even lists phone numbers people can call, along with information on how to respond to mental illness. So as we minister to others and seek to build faith, it is important to recognize how mental distress can affect our experience at Church. Inactivity due to mental health issues may spiral into a faith crisis. Faith comes by hearing the word (Romans 10:17), and faith grows as we nourish the seeds of faith (Alma 32:37). Faith may begin to wither and weaken when persons reduce activity in the Church and isolate themselves from hearing the word.

Anxiety psychology probably impacts church participation in significant numbers in ways we may not have considered. Another interesting study is being conducted by Jana Reiss, who commissioned a survey of 541 former Latter day Saints to determine why they left the Church. She reports that among millennials, tied for first place among the reasons they gave for leaving the Church was that they “felt judged or misunderstood.”22 This is especially interesting in light of the fact that “the defining feature of social anxiety disorder, also [sometimes] called social phobia, is intense anxiety or fear of being judged, negatively [Page 81]evaluated, or rejected in a social or performance situation.” 23 Of course, all of us experience some concern over being judged by others. But when the concern has begun to interfere with normal activities, this ordinary concern may develop into a psychological disorder. This is a condition that “affects approximately 15 million American adults and is the second most commonly diagnosed anxiety disorder following specific phobia. The average age of onset for social anxiety disorder is during the teenage years,” just the time when we see many begin to drift away from the Church. There are effective treatments available for social anxiety disorders through therapies and other means. Sadly, “despite the availability of effective treatments, fewer than 5% of people of with social anxiety disorder seek treatment in the year following initial onset and more than a third of people report symptoms for 10 or more years before seeking help.”24

Our Church expects us to be social. We are expected to speak and pray in Church, to teach lessons, read things aloud, answer questions in class, and call people on the phone, and we are sometimes asked to knock on the doors of strangers and ask them if they are willing to drastically change their lives. These are difficult things for anyone to do, but they can be among the hardest to do or simply impossible when someone experiences an anxiety disorder. Someone may be sitting in the lobby during sacrament meeting because he or she finds it difficult to be in a room with a large group. Or someone may go home after sacrament meeting because he or she feels worn out after spending an hour in a crowd of people and needs to take a break. We may wrongfully assume the person has a weak testimony. As a consequence, we may begin to treat such a person as one who lacks faith or who has repudiated us and our faith. If such people begin to experience a sense of rejection, they may further distance themselves from members of the Church, they may seek out more supportive communities, or tragically, they may simply suffer in isolation. It is not hard to imagine how this kind of separation from members of the Church and Church activity can ultimately result in a loss of testimony.

Similarly, a person who turns down a request to pray in church or give a talk may not have a lack of faith but may simply have a fear of speaking in public. “As a syndrome, social phobia is the third most common psychiatric disorder, with estimated life-time prevalence rates [Page 82]of 7‒13 per cent.”25 “The fear of public speaking is called glossophobia (or, informally, stage fright). It is believed to be the single most common phobia, affecting as much as 75% of the population.”26 It is said that people are more scared of public speaking than they are of dying. So when you attend a funeral, most people would rather be in the casket than giving the eulogy.

Someone who experiences maladaptive perfectionism or scrupulosity may feel overwhelmed with guilt and a painful sense of inadequacy in listening to a speaker talk about how her family reads the scriptures together every day or how her life was changed by a ministering brother or sister who came every month or how much she enjoys going to the temple every week. As others talk about how energized and uplifted they felt during the talk, a person with anxiety or depression may feel alone, scared and hopeless as that person wonders whether he or she really belongs in this church and whether going to heaven is really wanted if such perfect performance is expected.

Let me share one example of how mental distress can affect a faithful person and how wise leaders and family members can adapt the Church’s standardized ideals to meet the needs of individual circumstances.

We all know that Steve Young did not serve a mission. I always assumed the reason was that he felt a need to develop his football career, and considering the great influence he has been, I’ve never faulted him for that. But I was surprised to learn recently that he wanted badly to serve a mission, and the reason he did not had nothing to do with football. At the time he decided he would not serve a mission, he had been the eighth-string quarterback and had recently been moved to playing defense. More importantly, his decision had nothing to do with a lack of faith. Rather, as he thought about being away from home for two years, he began to feel overwhelmed with anxiety. It had been so difficult for him just to travel to Provo to go to school that he had not actually unpacked his clothes during the entire fall semester. Once he came home for the Christmas break, he decided to talk to his bishop and tell him he could not go on a mission. He felt terribly guilty.

[Page 83]But as he told his bishop that he decided it was best for him to continue going to BYU, his bishop told him about an impression he had received a couple of weeks earlier that Steve was going to visit him to tell him that he planned to return to school. The bishop also received the clear impression that he should tell Steve that it was right for him to return to BYU. Instead of trying to talk him into going on a mission, the bishop told him to serve Jesus Christ, live his religion, and be a great example.27 It was not until he was 32 years old that he was finally diagnosed with separation anxiety. 28

Steve Young had understanding parents and a bishop who was open to receiving a surprising revelation. It is not hard to imagine how, under a different set of circumstances, Steve Young may have decided that it was easier to leave the Church than it was to remain a member of a church that had expectations for him that he felt he could not satisfy.

As a church, we have gotten better at identifying the kinds of problems Steve Young faced and accommodating them. The process of applying for a mission call now includes considerations of mental health, and mission programs are adapted to the capabilities of the faithful youth who struggle with mental health issues. Calls can be issued for shorter assignments, can be closer to home, and assignments can be adapted to the strengths of faithful individuals without imposing crushing challenges. Our church is learning to deploy unique, faithful individuals into appropriate ministries without assuming that every person is the same and must adapt to a standardized pattern. Likewise, I believe apologists and ministering brothers and sisters can learn to adapt to the unique needs of people who are experiencing a faith crisis, including a faith crisis with mental health components.

Now, in introducing psychology as a factor that can contribute to disaffection from the Church, we hope we have made very clear that we do not think that any one factor causes a person to leave, including any particular psychological factor. In other words, mental illness is only one factor that could create a vulnerability that can lead to disaffection from the Church. Of course, like other factors mentioned, some people who struggle with mental health issues leave, and some stay.

[Page 84]Our point, of course, is that it may help those who experience mental health issues to stay if they received proper treatment, if they were to consider new perspectives on history, practice, and doctrine, or if they received appropriate kinds of support from Church leaders, friends and family. So it is our hope in introducing this topic that we can encourage people to be more aware of mental illness issues and seek help for themselves and others.

A significant amount of research demonstrates that religion has a positive effect on mental health. Daniel K. Judd found that “the overall body of research from the early part of the twentieth century to the present supports the conclusion that Latter day Saints who live their lives consistent with the teachings of their faith experience greater well being, increased marital and family stability, less delinquency, less depression, less anxiety, less suicide, and less substance abuse than those who do not.”29 As Daniel Peterson explained at last year’s FairMormon conference, regular church attendance is associated with “a roughly 30 percent reduction in mortality over 16 years of follow-up; a five-fold reduction in the likelihood of suicide; and a 30 percent reduction in the incidence of depression.”30 This suggests that if a person struggles with mental illness, leaving the Church would be counter-productive with respect to mental health. Yet it seems that some people who experience mental illness choose to disengage from church activity in response to struggles they experience, perhaps assuming that leaving the Church will resolve their mental anxieties or depression.

This response would not be unlike that of a woman I heard about recently who had panic attacks when she entered parking garages. She initially responded to this by avoiding parking garages. Of course this made her life more difficult, since she often had to park a long way from where she wanted to go. Once she sought treatment for her anxieties, she learned how to begin using a parking garage again, which made her life easier and happier.

Similarly, if a person is distressed because of church activity, the answer would not be to stop going to church. Some may feel that it is [Page 85]church that is causing their depression and anxiety, but upon leaving, the mental illness does not go away. They have simply abandoned something that could have helped them. So the proper thing to do would be to seek treatment so those persons are able to gain all of the social, intellectual, spiritual, and mental health benefits that come from church activity.

In presenting these ideas, we do not mean to suggest that there are no issues of Church history or doctrine that are confusing or upsetting, or that Church members and Church leaders never do anything that might be considered offensive. We hope that you will take away from this that when someone with mental illness faces a challenging situation, there are things we can do as friends, family members, and Church leaders to help. Of course, there are those who will say we are stigmatizing those who leave and are suggesting we can dismiss those who leave the Church as merely being crazy. We are most certainly not saying that. However, the only way to avoid the accusation would be to simply ignore the problem. If we were to ignore the fact that mental illness can make it difficult for some people to remain active in the Church, we would be ignoring an opportunity and perhaps shirking a duty to help bear one another’s burdens, to mourn with those who mourn, and to comfort those who stand in need of comfort (Mosiah 18:8‒9).

Just as there are a variety of reasons why people leave, there are a variety of things we can do to help them to stay. So we would like to turn now to a discussion of some of the key features of mental distress that can affect Church activity and what friends, family, Church leaders, and individuals themselves can do to respond to the challenges posed by mental distress.

Features of Mental Distress That May Present Barriers

to Belief and Participation

In this section, we’ll look at elements which contribute to mental distress and which also may block religious belief and participation. We will then consider ways that people can get help when suffering from mental distress.

One way to understand mental distress is to consider it through the lens of cognitive psychology, which is the basis of one of the most common evidence-based treatments for depression,31 and one of the most effective.32 Cognitive therapy says there is a link between what we think, how we feel, [Page 86]and what we do.33 Our thoughts influence our emotions, and our emotions influence our actions. Using this model, mental distress, which is manifest by our emotions, is viewed as being impacted by our way of thinking. A number of distorted ways of thinking have been identified as contributing to mental disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder.

As we will more fully explain, the cognitive distortions that contribute to mental distress can also be seen as barriers to belief and participation in religious activities. Mental distress is built upon cognitive distortions. Religious belief and participation may be negatively affected or blocked by those distorted ways of thinking.

For example, one common cognitive distortion is “All-or-Nothing Thinking.” Such thinking causes us to view the world in strict, mutually exclusive categories. This way of thinking contributes to depressed mood because when one categorizes one’s experience strictly between perfect and ruined, most experiences will end up in the ruined category — even if the person is nearly perfect. It’s either all or nothing. There is no in-between. This distortion may affect religious thinking by causing a person to expect that unless every aspect of doctrine makes sense, none of it can be true. It’s either all or nothing.

Another common distortion is Overgeneralization, which causes people to view a single event as a never-ending pattern. This pattern often includes the words always and never. This way of thinking contributes to depressed mood by incorrectly concluding that experience has only been of one type while overlooking other aspects of the experience. A single event is not the same as a never-ending pattern, but Overgeneralization would have you believe otherwise. This way of thinking may affect religious belief and participation by inaccurately assigning frequency to religious experience (e.g., when an answer to prayer is slow in coming, such people may tell themselves that their prayers never get answers, and so they stop praying entirely).

Mental Filter is another common cognitive distortion, causing people to pick one aspect of a situation and make that the focus of their attention while ignoring and filtering out other equally important aspects. This way of thinking contributes to depressed mood by orienting to only one aspect of a given situation — usually the negative or unfavorable aspect. An example of this would be when a person focuses on one unkind thing [Page 87]said or done to them at church while ignoring or filtering out the many other kind things that have been said or done to them there.

There are other types of cognitive distortions, but the point to be made is that mental distress is sometimes significantly fueled by cognitive distortions. Such distorted thinking may also serve as a barrier to religious belief and participation.

Fundamental to mental distress related to anxiety is the Intolerance of Uncertainty, or fear of the unknown. Those who struggle with anxiety tend to have higher intolerance of uncertainty, as manifest by persistent thoughts about the unknowns in a particular situation.34 Dwelling on the unknowns is a surefire way to increase anxious feelings. In other words, focusing on the unknowns, rather than the knowns, will create mental distress. In the words of the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, “He who fears he shall suffer, already suffers what he fears.”

Anxiety may also arise when new information conflicts with old. This conflict may make it unclear how to proceed and result in inconsistent thoughts, beliefs or attitudes. Such internal conflict is often referred to as cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance may cause us to choose from the following responses: reject the new information as false, consider the new information as unimportant, suspend judgment (“putting it on the shelf,” as discussed above), accept or reject the new information but with a greater understanding of context and definitions, or reject the old information (for example, rather than take the time to process how one’s former assumptions about Church history and doctrine might need to be readjusted, one might hastily decide the Church is not true in order to more quickly resolve the anxiety created by cognitive dissonance and uncertainty).

Besides creating a depressed or anxious mood, these distortions can also make it difficult to focus on the more subtle influence of what we call “the still, small voice,” thereby creating a sense of distance or isolation [Page 88]from God and communication with Him, which may be erroneously interpreted as “God doesn’t care or isn’t there,” instead of being more accurately seen as distorted thinking getting in the way. Some report that the medications they take also have the effect of muting their sensitivity to those spiritual feelings.

In summary, then, cognitive distortions contribute to mental distress. Those distorted ways of thinking affect our mood. Cognitive distortions may also serve to undermine the process of religious belief and participation by creating distorted ways of thinking that make it difficult to process new information when compared to information we already have.

Ways in Which People Can Get Help

So when a person is experiencing mental distress, what can be done? How can that person be helped? In this section we’ll consider what can be done by the individual, friends and family, and the Church and Church leaders. Finally we’ll talk about the prospect of professional help.

It is useful to think about helping people with mental distress as three concentric circles. The first, in the center, is Self. Ultimately, the responsibility for overcoming mental distress lies with the individual. Unless the individual is motivated and engaged, very little progress will be made. Next is Family and Friends. These are the people closest to the person in need. They are those most intimately connected to the individual, who have the most access. Next, there is the Church. The Church consists of neighbors and leaders who also know and love the individual but are not as intimately acquainted with the individual, perhaps, as family and friends.

The Individual

Healthy practices that a person may adopt to help him or herself include exercise,35 adequate rest, proper diet, and developing social connections.36 Developing attitudes of generosity37 and gratitude38 have [Page 89]also been shown to be helpful for maintaining good mental health. These practices are clinically proven to contribute to good mental health.

Family and Friends

Family and friends can help by knowing what to say (and what not to say), having the right attitude toward mental illness, and helping those afflicted make a plan of action. For the most part, the things to say should be messages of support and presence. Words can help or hurt. Efforts to explain or to fix usually have the unintended result of making the person feel bad or wrong for their condition. Friends and family don’t have to fix their loved one or the situation he or she faces, but they should try to reassure and comfort them.

There is no way to list all the things to say or do for a loved one with emotional distress, but there are a few attitudes to cultivate which, when followed, will give some ideas about what to say or do. Emotional distress is a real thing. Depression and anxiety are legitimate medical conditions. If we were in a major auto accident, we might have bandages and bruises that would be visible to others and would verify or validate our injuries. Major emotional trauma often has few physical signs but can be no less debilitating than physical injuries.

It is important to be patient with the person struggling with emotional distress and with the process of recovery and healing. There may be setbacks. That is common.

Communication is very important to develop and maintain understanding among family and friends. Ask questions and make observations. Share your thoughts and feelings and ask the loved one about his or hers. You may be surprised at what the loved one says.

Accommodation and adjustment are powerful ways to show support. Creative problem-solving with humor and good will has the potential to say, “I love you,” and “I am here for you,” in powerful ways. We wouldn’t be helping very much if we allowed our loved ones to avoid every distressing situation, but we can be resourceful in how we help them to meet the challenges they face every day.

Part of meeting the challenges of every day is helping to develop a plan of action which might include education, self-care, and the use of available resources. Knowledge is power, and becoming knowledgeable about the condition one finds oneself in will help everyone know what to do. Self-care, as has been covered previously, is essential to feeling better emotionally. While we can’t provide self-care for our loved one, we can encourage and support his or her efforts for self-care. We can also help [Page 90]identify available resources which may be found through family support, Church leaders and the priesthood, the blessings associated with temple worship, and the help to be found through healthcare.

The Church

The Church can also help through existing doctrines, opportunities for activity, and shepherding from Church leaders. These three areas can contribute positively to alleviation of mental distress.

President Boyd K. Packer explained, “True doctrine, understood, changes attitudes and behavior.”39 President Packer lists two of the three elements of Cognitive Psychology in this statement: Thoughts and Actions, only he calls them Attitudes and Behavior. If attitudes and behavior are changed by true doctrine, it is reasonable to conclude that feelings could also be changed by true doctrine.

Some interesting research has found this to be the case: that true doctrine does change feelings. One study of Latter day Saint people found that believing God is a loving God (a true doctrine) contributed to limiting or reducing anxious traits in those who held that belief. It also found that those who hold a view of God that is less loving or more controlling than what is commonly taught in Latter day Saint doctrine were more likely to endorse more serious or frequent anxious traits.40

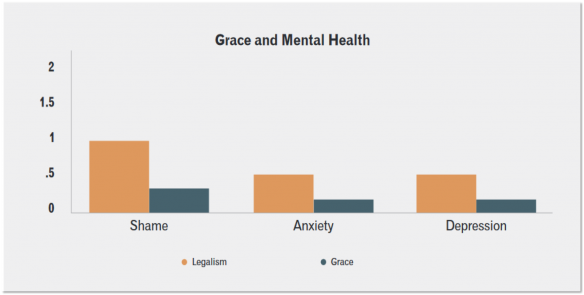

Other research has also found that increased views of the lovingness of God are most strongly related to a reduction of emotional symptoms for Latter day Saint people. In other words, subscribing to the doctrine that God is our father and He is perfectly loving appears to have the effect of reducing mental distress. Similarly, other researchers found that those who reported having an experience confirming the doctrine of God’s grace as taught by the Church had a positive relationship with mental health while those who had a more legalistic view of God’s dealings with his children correlated with decreased mental health.41

As shown in Figure 1, there is a stark difference in levels of shame, anxiety and depression between Latter day Saint Church members who view God through a construct of works being the most important (called “Legalism”) and those who view grace as the most important. As one can [Page 91]see, those with a Legalism outlook had noticeably higher scores on shame, anxiety, and depression than did the members with a grace outlook.

Figure 1. Grace and Mental Health

Association with the Church also brings opportunities for church activity. Activity in the Church produces social connection through serving others, teaching and learning from others, and working toward the common good. As mentioned earlier, social connection can also help reduce mental distress.

Church Leaders

Church leaders are in a position to have a powerful impact on those struggling with mental distress. Demonstrating compassion and a willingness to be attentive to the afflicted member can be a great comfort to the struggling member. As noted above, helping the brother or sister to develop a plan of action can also be very helpful and provide focus and motivation to the distressed. In addition, mobilizing ward resources may be appropriate.

Ward resources include involving the ward council, ministering brothers and sisters, and specifically called ward specialists. There may be ward temporal resources that could be brought to bear on the situation. Also, inspired ecclesiastical counseling could be included.

As demonstrated earlier, true doctrine changes attitudes and behavior, and there is evidence that it also can alleviate mental distress. If that is true, then teaching the pure word of God could be seen as important medicine for those who are distressed — and for all of us, really. When it comes to counseling from ecclesiastical leaders, consider how many true doctrines there are to understand and how they might change a person’s functioning if they were better understood.

[Page 92]Professional Help

Sometimes, the efforts of the individual and the support of family, friends, and the Church do not have sufficient impact on the emotional distress. When this is the case, it may be time to seek professional help. When the loved one is not responding sufficiently to the help offered or he or she is not maintaining the progress that should have been made, it may be that the problem is of a psychological nature, and professional help is required. One way to think about the severity of a loved one’s symptoms is to consider the amount of distress combined with the inability to control the symptoms combined with the frequency of the difficulties.

For most mental disorders related to depression and anxiety, the research is clear that professional counseling is an effective treatment.42

For depression and anxiety, counseling and medication appear to be equally effective. For some people, the combination of counseling and medication will be more beneficial than either treatment separately.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which focuses on the link between our thoughts, feelings, and actions, is one of the most common evidence based therapies for depression.43 Such therapy also appears to be one of the most effective.44

In recent addresses, Elder Holland has discussed his struggle with depression. Clearly, the fact that one experiences anxiety or depression does not mean that one cannot fully participate in and accept significant responsibilities in the Church. He said, “If things continue to be debilitating, seek the advice of reputable people with certified training, professional skills, and good values. Be honest with them about your history and your struggles. Prayerfully and responsibly consider the counsel they give and the solutions they prescribe. If you had appendicitis, God would expect you to seek a priesthood blessing and get the best medical care available. So too with emotional disorders. Our Father in Heaven expects us to use all of the marvelous gifts He has provided in this glorious dispensation.”45

Summary

We’ve been talking about mental distress and its potential to affect religious belief and participation. Some interesting research suggests [Page 93]that the factors which produce depressive and anxious symptoms are also those which make it difficult to navigate conflicting information such as may exist about the Church’s history, policies, and doctrine. There are a number of things individuals can do for themselves when experiencing depressive or anxious symptoms, and there are things that friends, family, and Church leaders may do for those individuals as well. Sometimes professional help is needed to address the mental distress.

We hope this presentation can be seen as a step toward more clearly understanding the factors that contribute to disaffection from the Church and what can be done to help ourselves and others remain close to the Church and the salvation found therein.

Go here to see the 66 thoughts on ““Barriers to Belief: Mental Distress and Disaffection from the Church”” or to comment on it.