When reading the LDS Book of Abraham, readers’ attention is often drawn to the “Facsimiles” that accompany that book, which are a frequent source of wonder and awe to many. While perhaps not as mesmerizing and mystifying as Facs. 2, the first facsimile has one figure in particular that begs for some analysis.

In the narrative of the Abraham 1, we are told that this image is included by Abraham to illustrate the situation in which he found himself — about to be sacrificed by the priest of Elkanah/Pharaoh on the “bedstead” altar, which was like the one depicted. His “fathers,” whom he had tried to convince to give up their idol worship, have turned him over to the idolatrous priest. However, just before he is sacrificed (in a scene reminiscent of the sacrifice of Isaac), Abraham tells us that the Angel of the Lord’s presence comes to save him, unlooses his bands and (after an extended dialogue) smites the priest of Elkanah. What is particularly significant in this story is that the Angel of the Presence announces himself to be Jehovah – whom most Bible readers would not consider to be the oft-mentioned “Angel of the Presence” of the Old Testament. ((However, Margaret Barker provides abundant evidence that this indeed was the ancient understanding, see her The Great Angel: A Study of Israel’s Second God (Louisville: W/JKP, 1992).))

So Jehovah came down as an angel (remember angel = Hebrew malak = messenger) to save Abraham. However, when you look at the facsimile, the figure (fig. 1) that Joseph Smith identifies as “The Angel of the Lord” is a bird! Why is the Angel of the Lord — Jehovah himself, no less — depicted as, or equated with, a bird?

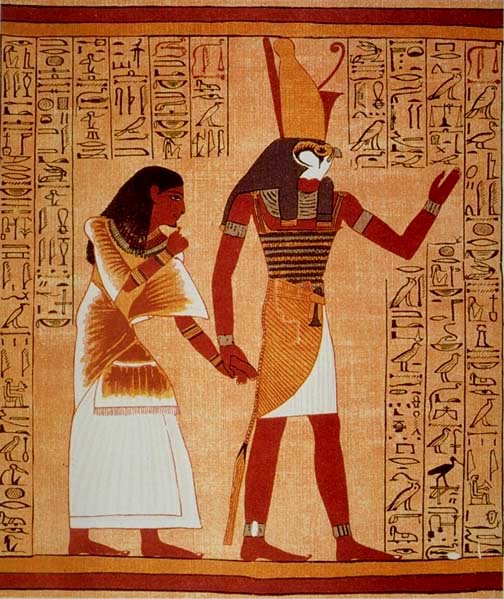

Although I pose it as an exasperating conundrum, the equation of a divine being with a bird should not be very surprising. The Holy Ghost, for example, is commonly represented by a dove. Anciently, it was common to employ this imagery to depict different gods. Very pertinent to our facsimile is the ancient Egyptian tradition of depicting the savior-god Horus as a hawk. As BYU professor James Harris notes, the bird in this facsimile (in its wider Egyptian context) likely does not represent the “ba“-bird, but “Horus (the hawk) who delivered his father Osiris from death just as a personage represented by a hawk delivered Abraham from death.” ((James R. Harris, “The Facsimiles of the Book of Abraham” in Milton R. Hunter, Pearl of Great Price Commentary, accessed online at http://www.gospelink.com/library/document/17396?highlight=1, on Feb. 11, 2010.))

(Just for fun, compare the above image to Abr. 1:18)

While we may expect an ancient Egyptian pictogram to depict a god as a bird, we can consider it rather odd that Joseph Smith would have so readily made the connection, especially since this association is not made clear in the text (nor is it common in Christianity to depict the Father or Son as a bird). What would be even more interesting is if their were some other evidence specifically linking the story of Abraham to an image of Jehovah/Yahweh as a bird.

We do find such an association in the Slavonic text of the Apocalypse of Abraham. Although we know it only from Old Slavonic Christian translations made in approximately the 15th century AD, scholars believe that the original was likely written in Hebrew in Palestine, possibly as early as the 1st century. We know that the text became popular among many early Christians, who ended up being the only ones who preserved it.

In the Apocalypse of Abraham (ApAb), after an extended sequence in which Abraham rejects and destroys the idols of his father, Abraham seeks the true God, the Creator of all things. God answers Abraham and sends to him the Angel of his Presence. In the text, this angel is called Iaoel/Jaoel or “Yahoel”– which was likely meant to be a variation of “Yahweh-El.” The angel is called Iaoel “of the same name” (10:3), probably meaning that his name was understood to be the same as God’s (Yahweh). The text describes this angel as being “in the likeness of a man” (10:4). 11:2-4 describes him as having a body like sapphire, a face like chrysolite, and hair like snow—a description which reminds us of the anthropomorphic descriptions of Deity found in the Old Testament and many pseudepigraphal texts. He is described as having a turban, purple robes, and golden staff, which recall a royal/high priestly figure. So far, this seems like a pretty standard (albeit notably anthropomorphic) description of Yahweh/the Angel of Yahweh.

But what about the bird connection? Dr. Andrei Orlov notes that Kulik’s translation of ApAb includes a detail which Rubinkiewicz’ is missing: the rendering of the Slavonic word “ногуего,” as “griffin” (“the appearance of the griffin’s body was like sapphire,…”). According to Orlov, the author depicted Yahoel as both man and bird. ((Andrei Orlov, “The Pteromorphic Angelology of the Apocalypse of Abraham,” CBQ 71 (2009) 830–42.))

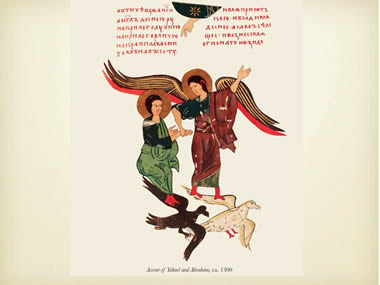

Ascent of Yahoel and Abraham — my thanks to Jeffrey Bradshaw for this image

Re your comment that the Facsimile 1:2,4 “image is included by Abraham to illustrate the situation in which he found himself — about to be sacrificed by the priest of Elkanah/Pharaoh on the ‘bedstead’ altar, which was like the one depicted,” it is likely that this Egyptian image was created a couple of millennia after Abraham by members of the Jewish community in Egypt as part of a long-term redaction process. Such redactors may have had in mind the Egyptian nmt “place of execution, slaughtering block” (Pyramid Texts 811d, 865; T. G. Allen, Book of the Dead, Spell 130 b S 2; Faulkner, Pyramid Texts), nmmyt “bed, couch, bier” ( Budge, Hieroglyphic Dictionary, 375), and nmʻ “go to sleep” (with lion-couch determinative; Faulkner, Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, 132-133).

However, since BofA 1:12-13, has it that the illustration “was made after the form of a bedstead, such as was had among the Chaldeans,” one should probably be thinking of an Aramean or Amorite style bed, perhaps like the Akkadian eršu “bed” (= Sumerian u2, ĝeš-nud, GÌŠ.NÁ).

Also, it is Elkenah, not Elkanah (the KJV spelling), although they each have the same etymology.

In the second figure where Horus is leading the pharaoh I presume, where it that figure from?

That figure is from the Book of the Dead Papyrus Ani (British Museum 10470), and can be seen in larger context in Nibley, Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri, 2nd ed., 447 (fig. 145), citing E. Budge, Book of the Dead, Papyrus of Ani, II:374, III:plate 4.

I have to agree with Brant on the Poverty Point not being associated with the Angel of the Lord’s Presence in the Book of Abraham. Archaeology shows it was built 1650-700BC – a century before Lehi left Jerusalem. And it is not likely the Jaredites had Abraham’s record, since Abraham comes after the Tower. Given that birds often represent deity in many places in the world, there is no easy way to make a solid connection.

The carbon tested materials at Poverty Point dated from 2278 BC to AD 961 (John L. Gibson, Poverty Point: A Terminal Archaic Culture of the Lower Mississippi Valley, Second Edition with Revision 1999, p. 32). In the construction of earth mounds, the dirt from which they were made came from pits and trenches dug deep into the soil around them. Every basket of dirt that went into the building of a mound was contaminated with the carbon-bearing particles and pieces of previous ages. Many of the samples for radiocarbon dating were retrieved by coring and augering. With these conditions, deciding which particles were from the time of construction would be nearly impossible, and at best, subjective. The age in which Poverty Point was constructed is therefore better determined by other factors, such as the examination of recovered art works.

Thanks, David. This shed a lot of new light (new to me) on Abraham. I’ve really appreciated reading the work on the translation and content of the Book of Abraham recently. It’s helped a great deal to get over the hump of the book being “difficult/weird” to a point where I can understand some of the sublime doctrine better. My instinct has always been that there’s a purpose behind the “problem” of the facsimiles, and this is helpful.

Hey Zach!

I’m glad that was of some help. The controversy surrounding the Book of Abraham is unfortunate as there are so many theological gems in the book. Some aspects may seem odd, but the book is truly a pearl in the LDS canon.

David,

The Sacred Bird motif is found throughout Ancient America. For example, the entire Temple Mound (Mound A) at the archaeology site at Poverty Point in Louisiana is in the shape of a bird very similar to the drawing in Facsimile 1, and several stone carvings of the same bird shape have been excavated there. Similarities between the Poverty Point Bird Relief Carvings and the Symbol of Jehovah in the Book of Abraham include the following:

1. Both birds are erect.

2. Both birds have curved, drooping wings.

3. Both birds are facing the same direction in profile.

4. Both birds are standing on broad tails.

The Brass Plates came through Joseph of Egypt and were written in Egyptian (1 Nephi 5:14; 2 Nephi 3:1-16; Mosiah 1:4). They would surely have contained the writings and drawings of Abraham, who was the great-grandfather of Joseph. A bird symbol representing God was common throughout North America and is thought to have originated with Christ’s coming to America and His descention from heaven. These carvings and this bird mound at Poverty Point suggests that the Sacred Bird symbol came earlier, perhaps from Abraham’s representation of Jehovah. It is highly improbable that the inhabitants of Poverty Point could have carved such a close representation of Abraham’s symbol of Jehovah without having seen it. The Brass Plates are the most likely and logical source of their knowledge of this Sacred Bird. This Sacred Bird design, similar to Abraham’s drawing, is also represented at other archaeological sites throughout America, particularly at Ocmulgee and at Etowah in the state of Georgia.

The Sacred Bird motif is prominent throughout all America. The bird costumes, feathers and headdresses worn by priests and medicine men in all Ancient American cultures may have been a representation of the power of the priesthood of God, which they held, or thought they held, or imitated. It may all have originated from the drawing of Abraham.

Moses provided the symbol of Jesus Christ as a serpent. After Christ’s coming to America, the combination symbol of the Feathered Serpent is the perfect symbolic representation of the union of the spirit of Jehovah with the body of Jesus Christ.

Birds are used in multiple iconographies from widely different locations. It is hardly surprising as there are birds all over the world. The presence of a bird image in one culture is more likely to be independent unless there are some very detailed correlations (including contexts).

I am on record (and probably repeat to everyone else’s boredom) that the feathered serpent imagery has absolutely nothing to do with Christ’s appearance in the Americas. This isn’t the place to repeat the evidence, but the only evidence that makes it appear likely comes from distorted post-Conquest Spanish writers–and their writings are typically distorted just a little more to make the connection to Christ rather than to St. Thomas (their chosen explanation for what they saw as correlations to Christianity).

I believe that the scripture in Matthew 10:16 affirms that in Christ’s own words he establishes the bird/serpent motif throughout the world, not just the Americas. He was speaking at the time to His disciples in the Old World. He would present the same idea to His disciples in the New World, of course, because He is unchangeable. I find the “Feathered Serpent” motif a logical interpretation for people that relied on oral traditions as the original idea devolved from the gentle Dove and wise Serpent from Matthew 10:16. Actually, the Serpent was a type for the Christ-Healer in the desert as the Children of Israel were bitten by the fiery serpents, and only survived as they looked to the symbol of the serpent on the staff. There is precedent in the Old and New Worlds for both the Serpent and the Dove. This motif is found in ancient China as well.

A thought regarding the symbolism of the Serpent on the Pole:

Since Genesis the serpent has generally represented Satan. So why did the Lord command Moses use the serpent to represent Christ? I would suggest that just as it was the venom from the serpents that was killing the Israelites, it is the venom from Satan, or sin, that is killing us all. Christ took all of that sin upon himself in the Garden of Gethsemane and on the cross. I believe that the serpent on the pole represents the body of Christ on the cross, laden with all of the sins of the world.

I’m sure that you understand that you are giving your personal reading of the scriptures. It is a way to read them. However, it is a reading that imposes a more complex theological meaning on the simpler imagery of the Nechushtan. Reading it as Christ is possible backwards, but it was an image that could not have informed the Israelites. They had to find meaning in it rather immediately, and it couldn’t be what you are suggesting.

There is nothing wrong with reading the scriptures and applying them to our world, but using our world to assume ancient history is not effective.

Christ laden with out sins on the cross is a modern idea? You don’t think Moses understood that? I think it was taught to Adam.

Brant,

Reading the Nechushtan as Christ is not a personal, nor a modern interpretation. This interpretation comes from Nephi (2 Nephi 25:20), Helaman (8:14-15), Nephi son of Helaman (Alma 33:18-22), and Jesus Christ Himself when he said:

“And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life.” (John 3:14-15)

Theodore, it is a question of reading. I understand the way you are reading those verses (though it is a bit strained in the case of 2 Ne. 25:20).

There are two aspects of the brazen serpent that are interesting. The first is the simple nature of the command “look and live.” The was an easily transferable lesson to the Atoning Messiah as one to whom one might also look for a remission of sin.

The second is the fact that the brazen serpent was lifted up. That is emphasized in John. In John, the lifting is emphasized and the looking is assumed. In the Book of Mormon the lifting up doesn’t become part of the symbolism as it does in John. That difference is interesting and appropriate for the different circumstances.

Of course modern readers are familiar with John and impose both images as symbolic readings for the Nephite scripture.

Brant

The fact that “there are birds everywhere” does not explain the unique similarities between the Abraham’s symbolic depiction of Jehovah and the Poverty Point Bird Carving and its sacredness.

Thanks for your comments here, Theodore, Brant, and Victoria.

There are certainly some interesting parallels between the bird imagery I have discussed here and the examples you mention from North America.

I tend to trust Bro. Gardner on these topics, as he knows much more about it than I do, but your points are certainly interesting.

Thanks!

Isn’t that image from one of the Slavonic texts of the Apocalypse of Abraham.

Yes, David, it is an image from the Apocalypse of Abraham as found in the Codex Sylvester. Jeffrey Bradshaw took a photo of the actual codex, I believe.