This series is cross-posted with the permission of Book of Mormon Central

from their website at Pearl of Great Price Central

Figure 1. Jan van Eyck, ca. 1395-1441: Offering of Abel and Cain, 1425-1429.

This carefully conceived scene, executed in grisaille to decorate the top of a niche containing a portrait of Adam, is part of a set of large altarpiece panel paintings in the Joost Vijdt chapel in the Cathedral of St. Bavon at Ghent, Belgium. The portrayal of Abel lifting up the lamb “prefigures both the sacrifice of Christ and the Eucharist.”[1] The contrasting choices of Cain and Abel with respect to their covenantal obligations typify the account of the parting of the ways of righteousness and wickedness that begins in Moses 5. Of those who follow the way of wickedness, Jude wrote: “Woe unto them! For they have gone in the way of Cain.”[2]

Relating the themes of opposition and agency that are portrayed in the story of Cain and Abel, Hugh Nibley frequently wrote about “the inescapable choice between Two Ways.”[3] This ancient doctrine “proclaims that there lie before every human … two roads between which a choice must be made. The one is the road of darkness, the way of evil; the other, the way of light. Every man must choose between the two every day of his life; that choosing is the most important thing he does. … He will be judged by God in the proper time and place. Meantime he must be free, perfectly free, to choose his own way.”[4]

In this essay, we will outline the five celestial laws of the New and Everlasting Covenant, first revealed in the days of Adam.[5] During periods of darkness, the ordinances associated with these laws were generally withdrawn from the earth, however their shadows have persisted in religions and cultures the world over.[6] Nowhere in scripture are these teachings better preserved than in the Book of Moses. Not only do we find each law there in proper sequence, but also, in every case, we discover stories that illustrate their application, both positive and negative. Indeed, it seems as if the telling of the stories of Moses 5-8 were deliberately structured in order to highlight the contrast between those who accepted and those who rejected the laws of heaven.[7]

The Five Celestial Laws

Specific teachings about the five celestial laws are to be had in the temple. Elder Ezra Taft Benson elaborates:

Celestial laws, embodied in certain ordinances belonging to the Church of Jesus Christ, are complied with by voluntary covenants. The laws are spiritual. Thus, our Father in Heaven has ordained certain holy sanctuaries, called temples, in which these laws may be fully explained, the laws include the law of obedience and sacrifice, the law of the gospel, the law of chastity, and the law of consecration.[8]

Why are these called the celestial laws? Because only those who are “sanctified”[9] through their faithfulness to them, coupled with the redeeming power of the Atonement, can “abide a celestial glory.”[10] Otherwise, they must “inherit another kingdom, even that of a terrestrial kingdom, or that of a telestial kingdom.”[11] The Lord further explains:

that which is governed by law is also preserved by law and perfected and sanctified by the same.

That which breaketh a law, and abideth not by law, but seeketh to become a law unto itself, and willeth to abide in sin, and altogether abideth in sin, cannot be sanctified by law, neither by mercy, justice, nor judgment. Therefore they must remain filthy still.[12]

By means of obedience to these laws, the covenant people “remove themselves utterly from the world, to be completely different, holy, set apart, chosen, special, peculiar (‘am segullah—sealed), not like any other people on the face of the earth.”[13]

In ancient and modern temples, the story of events surrounding the Creation and the Fall has always provided the context for the presentation of the laws and the making of covenants that form part of the temple endowment.[14] Thus, it is not surprising to find that a similar pattern of interleaving history and covenant-making themes may have also helped dictate both the structure and the content of the material selected for inclusion in the Book of Moses. Writes Mark Johnson:

Throughout the text [of the Book of Moses], the author stops the historic portions of the story and weaves into the narrative framework ritual acts such as sacrifice and sacrament; ordinances such as baptism, washings and the gift of the Holy Ghost; and oaths and covenants, such as obedience to marital obligations and oaths of property consecration. … [If we assume that material similar to Moses 1-8 might have served as a temple text, it would be expected that as] this history was recited, acts, ordinances and ceremonies would have been performed during this reading. For instance, during the story of Enoch and his city of Zion, members of the attending congregation would be put under oath to be a chosen, covenant people and to keep all things in common, with all their property belonging to the Lord.[15]

A precedent for the idea of structuring key scriptural accounts to be consistent with a pattern of covenant-making can be found in John W. Welch’s analysis of 3 Nephi 11-18, where he showed that: “The commandments … are not only the same as the main commandments always issued at the temple, but they appear largely in the same order.”[16] In a similar vein, David Noel Freedman found evidence for an opposite pattern of covenant-breaking in the “Primary History” of the Old Testament. He argued that the biblical record was deliberately structured to reveal a sequence where the each of the commandments were broken one by one, “a pattern of defiance of the Covenant with God that inexorably [led] to the downfall of the nation of Israel.”[17]

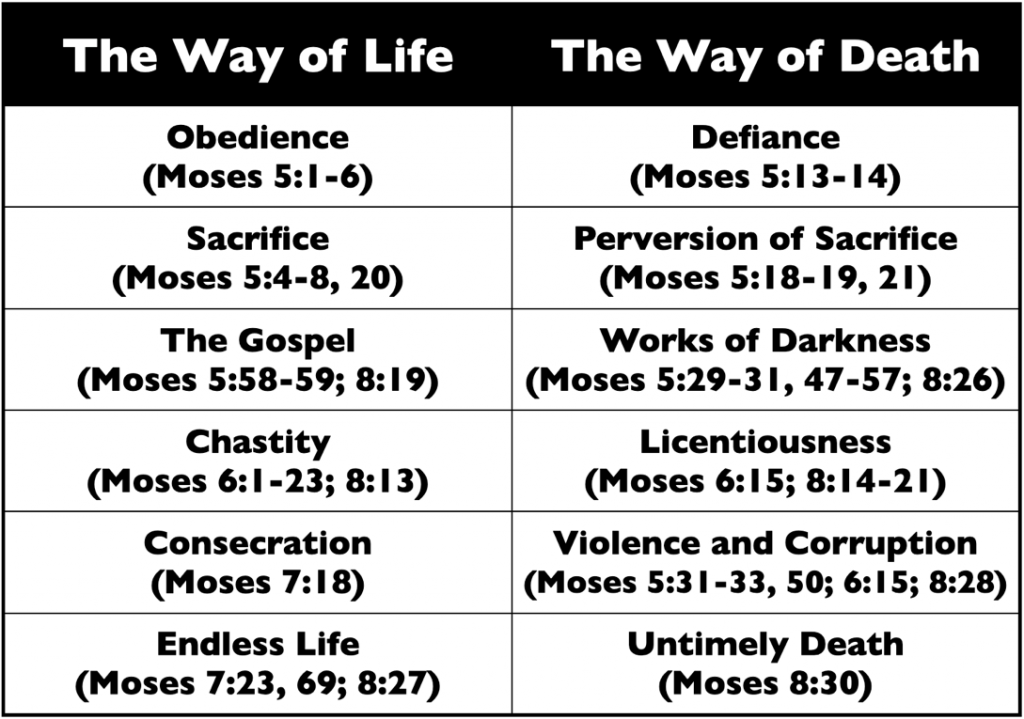

Figure 2. The Progressive Separation of the Two Ways

The figure above illustrates the progressive separation of the “two ways” due to analogous sequences of covenant-keeping and covenant-breaking documented in the Book of Moses. An interesting aspect of looking at the history of Adam through Enoch as a temple text is that—like Christ’s great sermons and the biblical text of the “Primary History”—the series of covenant-related themes unfolds in what appears to be a definite order of progression. Also remarkable is the fact that both the ultimate consequences of covenant-keeping as well as those of covenant-breaking are fully illustrated at the conclusion of the account: in the final two chapters of the Book of Moses, Enoch and his people receive the blessing of an endless life as they are taken up to the bosom of God[18] while the wicked experience untimely death in the destruction of the great Flood.[19]

Obedience vs. Defiance

Elder Bruce R. McConkie stated that: “Obedience is the first law of heaven, the cornerstone upon which all righteousness and progression rest.”[20] The reason why this is so is explained by Hugh Nibley:

If every choice I make expresses a preference, if the world I build up is the world I really love and want, then with every choice I am judging myself, proclaiming all the day long to God, angels, and my fellowmen where my real values lie, where my treasure is, the things to which I give supreme importance. Hence, in this life every moment provides a perfect and foolproof test of your real character, making this life a time of testing and probation.[21]

Latter-day Saint scripture recounts that God gave Adam and Eve a set of “second commandments” after the Fall, which included a covenant of obedience. This idea recalls a Christian tradition that God made a covenant with Adam—“ere he came out of the garden, [when he was by the tree] whereof Eve took the fruit and gave it him to eat.”[22] It seems reasonable to suppose that the law of sacrifice, a companion to the law of obedience, was also given to Adam and Eve at this time, before they came to live in the mortal world.[23]

Moses 5:1-6 highlights the subsequent obedience of Adam and Eve by enumerating their faithfulness to each of the commandments they had been given. Adam, with his fellow-laborer Eve, began to “till the earth, and to have dominion over all the beasts of the field, and to eat his bread by the sweat of his brow.”[24] Likewise Eve fulfilled the commission she had received in the Garden of Eden and “bare … sons and daughters, and they began to replenish the earth.”[25] Moreover, “Adam was obedient to the commandments of the Lord” in obeying the law of sacrifice and offering “the firstlings of their flocks” for “many days,” despite the fact that he did not yet fully understand the reason why he had been thus commanded.[26]

Figure 3. Blind Obedience, Toulouse, France, 2009.

Later, in defiant counterpoint, Satan also came among the children of Adam and Eve demanding their obedience, “and he commanded them, saying: Believe it not; and they believed it not.” From that point on, many of them openly demonstrated that they “loved Satan more than God,” becoming “carnal, sensual, and devilish.”[27]

Though, in a general sense, the Fall was the cause of all mankind becoming carnal, sensual, and devilish “by nature,”[28] Moses 5:13 makes it clear that it was only “from that time” when men individually chose to reject the Gospel, demonstrating that they “loved Satan more than God,” that they fully suffered the effects of alienation from God. Such individuals remain “as though there was no redemption made,” “knowing evil from good, subjecting themselves to the devil.”[29] On the other hand, those who accept the Atonement of Christ become “free forever, knowing good from evil, to act for themselves and not be acted upon.”[30]

Sacrifice vs. Perversion of Sacrifice

President David O. McKay described the essence of the law of sacrifice as follows:

The first law of mortal life, self-preservation, would claim the most luscious fruit, the most tender meat, the softest down on which to lie. Selfishness, the law of nature would say, “I want the best; that is mine.” But God said: “Take of the firstlings of your herds and of your flocks.”[31] The best shall be given to God. … Thus should God become the center of our being.[32]

The Lectures on Faith further explain that:

When a man has offered in sacrifice all that he has for the truth’s sake, not even withholding his life, and believing before God that he has been called to make this sacrifice because he seeks to do his will, he does know, most assuredly, that God does and will accept his sacrifice and offering, and that he has not, nor will not seek his face in vain. Under these circumstances, then, he can obtain the faith necessary for him to lay hold on eternal life.[33]

Once Adam and Eve had passed their initial test of obedience to the laws they had been given in the Garden of Eden, God, seeing that it was “expedient that man should know concerning the things whereof he had appointed unto them … sent angels to converse with them … and made known unto them the plan of redemption.”[34] To Adam was explained that the law of sacrifice “is a similitude of the sacrifice of the Only Begotten of the Father, which is full of grace and truth.”[35]

Abel followed the pattern of his father in perfect obedience to God and offered a lamb in sacrifice. By way of contrast, Cain, at the command of Satan, “offered the fruit of the ground as a sacrifice, which was not symbolic of Christ’s great act of redemption. … Instead of purchasing a lamb or another animal that would serve as an appropriate sacrifice, he offered what he produced.”[36] Speaking of the reason Cain’s sacrifice was rejected, the Prophet Joseph Smith explained that “ordinances must be kept in the very way God has appointed,”[37] in this case by “the shedding of blood … [as] a type, by which man was to discern the great Sacrifice which God had prepared.”[38]

Figure 4. Ewe and Lambs, Lakes District, England, 2000.

Not only must the form of the ordinance comply with the divine pattern, but also the heart must be filled with the spirit of sincere repentance, since “the shedding of the blood of a beast could be beneficial to no man, except it was … done with an eye looking forward in faith on the power of that great Sacrifice for a remission of sins.”[39] Following the “great and last sacrifice”[40] of Jesus Christ, no further shedding of blood was required, but only the sacrifice of “a broken heart and a contrite spirit.”[41]

The Gospel vs. Works of Darkness

Although in a general sense, “the law of the Gospel embraces all laws, principles, and ordinances necessary for our exaltation,”[42] the interpretive context of the temple specifically brings to mind pointed instructions relating to Christlike behavior toward one’s fellow man. These instructions parallel some of the items prohibited in the community that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls, “such as laughing too loudly, gossiping, and immodest dress.”[43] Doctrine and Covenants 20:54, also bearing on this theme, instructs teachers in the Church that they should watch over members, assuring that there is “neither hardness with each other, neither lying, backbiting, nor evil speaking.” Likewise, members of the Kirtland School of the Prophets were told: “cease from all your light speeches, from all laughter, from all your lustful desires, from all your pride and light-mindedness, and from all your wicked doings.”[44] Thus, as Nibley summarizes, “the law of the Gospel requires self-control in everyday situations,”[45] putting “restraints on personal behavior” while “it mandates deportment … to make oneself agreeable to all.”[46] Elaborating on these qualities, he wrote:

As to light-mindedness, humor is not light-minded; it is insight into human foibles. … What is light-minded is kitsch, delight in shallow trivia; and the viewing of serious or tragic events with complacency or indifference. It is light-minded, as Brigham Young often observed, to take seriously and devote one’s interest to modes, styles, fads, and manners of speech and deportment that are passing and trivial, without solid worth or intellectual appeal. As to laughter, Joseph Smith had a hearty laugh that shook his whole frame; but it was a meaningful laugh, a good-humored laugh.[47] Loud laughter is the hollow laugh, the bray, the meaningless laugh of the soundtrack or the audience responding to prompting cards, or routinely laughing at every remark made, no matter how banal, in a situation comedy. Note that “idle thoughts and … excess of laughter” go together in Doctrine and Covenants 88:69.

As to light speech and speaking evil, my policy is to criticize only when asked to: nothing can be gained otherwise. But politicians are fair game—the Prophet Nathan soundly denounced David though he was “the Lord’s anointed,” but it was for his private and military hanky-panky, thinking only of his own appetites and interests.[48] Since nearly all gossip is outside the constructive frame, it qualifies as speaking evil.

As to lustful desires and unholy practices, such need no definition, one would think. Yet historically, the issue is a real one that arises from aberrations and perversions of the endowment among various “Hermetic” societies which, professing higher knowledge from above, resort to witchcraft, necromancy, and divination, with a strong leaning toward sexual license, as sanctioned and even required by their distorted mysteries.[49]

Conforming to the sequence of revealed laws found in other temple texts, the term “Gospel” occurs in the Book of Moses only twice—and in neither case does its order of appearance defy our expectation of consistency with the sequence of temple covenants.[50] Moses 5:58 tells of how through Adam’s effort “the Gospel began to be preached from the beginning.” Adam and Eve were tutored by holy messengers,[51] and he and Eve in turn “made all things known unto their sons and daughters.”[52] The mention of the Holy Ghost falling upon Adam[53] carries with it the implication that he had at that point already received the ordinance of baptism,[54] something that might have logically occurred soon after the angel’s explanation of the meaning of the law of sacrifice.[55]

The ordinance of baptism was followed by additional instruction concerning the plan of salvation given “by holy angels, … and by [God’s] own voice, and by the gift of the Holy Ghost.”[56] Bestowals of divine knowledge, the making of additional covenants, and the conferral of priesthood power must have surely accompanied these teachings.[57] “And thus all things were confirmed unto Adam, by an holy ordinance, and the Gospel [was] preached, and a decree [was] sent forth, that it should be in the world, until the end thereof.”[58]

Figure 5. Worship, Amsterdam Schipol Airport, 2009.

Sadly, scripture records that, despite Adam’s efforts to the contrary, “works of darkness began to prevail among the sons of men.”[59] Rejecting the covenants, the ordinances, and the universal scope of the brotherhood of the Gospel, they reveled in the exclusive nature of their “secret combination” by whose dark arts “they knew every man his brother,”[60] and they engaged in “wars and bloodshed … seeking for power.”[61]

Chastity vs. Licentiousness

Nibley writes that this covenant of “self-control”[62] places a “restraint on uncontrolled appetites, desires, and passions, for what could be more crippling on the path of eternal progression than those carnal obsessions which completely take over the mind and body?”[63] Both chastity outside of marriage and fidelity within marriage are required by this covenant,[64] as Welch explains in the context of Jesus’ Sermon at the Temple:

The new law [in 3 Nephi 12:27-30] imposes a strict prohibition against sexual intercourse outside of marriage and, intensifying the rules that prevailed under the old law, requires purity of heart and denial of these things. …

In connection with the law of chastity, Jesus teaches the importance of marriage by superseding the old law of divorcement with the new law of marriage: “It hath been written, that whosoever shall put away his wife, let him give her a writing of divorcement. Verily, verily, I say unto you, that whosoever shall put away his wife, saving for the cause of fornication, causeth her to commit adultery; and whoso shall marry her who is divorced committeth adultery”[65] … The context of the Sermon at the Temple suggests that this very demanding restriction applies only to husbands and wives who are bound by the eternal covenant relationship involved here. This explains the strictness of the rule completely, for eternal marriages can be dissolved only by proper authority and on justifiable grounds. Until they are so divorced, a couple remains covenantally married.[66]

The law of chastity is not mentioned specifically in the Book of Moses, but it does value the paradigm of orderly family lines in contrast to problems engendered by marrying outside the covenant. Moses 6:5–23 describes the ideal family order established by Adam and Eve. A celestial marriage order is also implied in Moses 8:13, where Noah and his righteous sons are mentioned. The patriarchal order of the priesthood “which was in the beginning” and “shall be in the end of the world also”[67] is depicted as presiding over a worthy succession of generations in the likeness and image of Adam,[68] just as Adam and Eve were made in the image and likeness of God.[69]

Figure 6. The Sons of God and the Daughters of Men, 1350.

However, in contrast to these “preachers of righteousness,”[70] extracanonical traditions speak of “fornication … spread from the sons of Cain” which, “flamed up” and tell how “in the fashion of beasts they would perform sodomy indiscriminately.”[71] Both the disregard of God’s law by the granddaughters of Noah who “sold themselves”[72] in marriage outside the covenant and the subversion of the established marriage selection process by the “children of men” are summed up by the term “licentiousness” (from Latin licentia = “freedom”—in the negative sense of the word). As for the mismatched wives, Nibley explains that the “daughters who had been initiated into a spiritual order, departed from it and broke their vows, mingling with those who observed only a carnal law.”[73] Additionally, the so-called “sons of God”[74] (a self-designation made in sarcasm by way of counterpoint to Noah’s description of them as the “children of men” in the preceding verse) were under condemnation. Though the Hebrew expression that equates to “took them wives”[75] is the normal one for legal marriage, the words “even as they chose” (or, in Westermann’s translation, “just as their fancy chose”[76]) would not have been as innocuous to ancient readers as they seem to modern ones. The choice of a mate is portrayed as a process of eyeing the “many beauties who take [one’s] fancy” rather than “discovery of a counterpart, which leads to living as one in marriage.”[77] The Hebrew expression underlying the phrase “the sons of men saw that those daughters were fair” deliberately parallels the temptation in Eden: “the woman saw that the tree … became pleasant to the eyes.”[78] The words describe a strong intensity of desire fueled by appetite — which Robert Alter renders in his translation as “lust to the eyes.”[79] In both cases, God’s law is subordinated to the appeal of the senses.[80]

Draper et al. observe that the words “eating and drinking, and marrying and giving in marriage” “convey a sense of both normalcy and prosperity,”[81] conditions of the mindset of the worldly in the time of Noah that Jesus said would recur in the last days.[82] The wining, dining, courtships, and weddings will continue right up to the great cataclysm of the Flood “while superficially all seems well. To the unobservant, it’s party time.”[83]

Consecration vs. Corruption and Violence

President Ezra Taft Benson has described the law of consecration as being “that we consecrate our time, talents, strength, property, and money for the upbuilding of the kingdom of God on this earth and the establishment of Zion.”[84] He notes that all the covenants made up to this point are preparatory, explaining that: “Until one abides by the laws of obedience, sacrifice, the gospel, and chastity, he cannot abide the law of consecration, which is the law pertaining to the celestial kingdom.”[85] Nibley similarly affirms that this law is “the consummation of the laws of obedience and sacrifice, is the threshold of the celestial kingdom, the last and hardest requirement made of men in this life”[86] and “can only be faced against sore temptation.”[87] In compensation for this supreme effort, President Harold B. Lee avers that to the “individual who thus is willing to consecrate himself, [will come] the greatest joy that can come to the human soul.”[88] Consecration is, as Welch affirms, the step that precedes perfection.[89]

Figure 7. Detail of a wall hanging illustrating a Manichaean account of Enoch showing palaces at the top of a tree-like sacred mountain that surround a larger palace of Deity. Corresponding texts seem to describe events similar to the Book of Moses story of how Enoch and his people ascended to the bosom of God.

Moses 7 describes how Enoch succeeded in bringing a whole people to be sufficiently “pure in heart”[90] to fully live the law of consecration. In Zion, the “City of Holiness,”[91] the people “were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them.”[92] Moreover, it can be safely presumed that, as with the Nephites following the visit of Christ:

There were no contentions and disputations among them, and every man did deal justly one with another. And they had all things in common among them; therefore, there were no rich and poor, bond and free, but they were all made free, and partakers of the heavenly gift.[93]

Note that this ideal of economic reform is not based merely on the idea of fair division of property, but rather on the higher principle “that everything we have belongs to the Lord; therefore, the Lord may call upon us for any and all of the property which we have, because it belongs to Him.”[94]

Just as the life of Enoch can be regarded as a type of the spirit of consecration, so Lamech, who also lived in the seventh generation from Adam, serves as a scriptural example of its antitype. While Enoch and his people covenanted with the Lord to form an order of righteousness to ensure that there would be “no poor among them,”[95] Lamech, along with others members of his “secret combination,” “entered into a covenant with Satan” to enable the unchecked growth of his predatory order.[96] Lamech’s “secret works” contributed to the rapid erosion of the unity of the human family, culminating in a terrifying chaos where “a man’s hand was against his own brother, in administering death” and “seeking for power.”[97]

The meanings of the terms “corruption” and “violence,” as used by God to describe the state of the earth in Moses 8:28, are instructive. The core idea of being “corrupt” (Hebrew sahath) in all its occurrences the story of Noah is that of being “ruined” or “spoiled”[98]—in other words completely beyond redemption. Like the recalcitrant clay in the hands of the potter of Jeremiah 18:3-4, the people could no longer be formed to good use. The Hebrew term hamas (violence) corresponds to synonyms such as “‘falsehood,’ ‘deceit,’ or ‘bloodshed.’ It means, in general, the flagrant subversion of the ordered processes of law.”[99] We are presented with a picture of humankind, unredeemable and lawless, generating an ever-increasing legacy of ruin and anarchy. This description is in stark contrast to the just conduct of Noah.100]

In a striking echo of Moses 7:48, we are told in ancient sources that “[e]ven the earth complained and uttered lamentations.”[101] To Enoch, the Lord sorrowed:

Behold these thy brethren; they are the workmanship of mine own hands. … And … I [have] said … that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood … and among all the workmanship of my hands there has not been so great wickedness as among thy brethren … wherefore should not the heavens weep, seeing these shall suffer?[102]

Having witnessed the culmination of these bloody scenes of corruption and violence, God concluded to “destroy all flesh from off the earth.”[103 Like the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah, the wicked at last “were destroyed, because it was better for them to die, and thus be deprived of their agency, which they abused, than entail so much misery on their posterity, and bring ruin upon millions of unborn persons.”104] Thus, the successive breaking of each of the covenants triggered the same sort of three-strikes-and-you’re-out consequence that David Noel Freedman described in his analysis of the one-by-one breaking of each of the Ten Commandments in the Primary History of the Old Testament.

The promise of being “received … into [God’s] own bosom”[105 like Enoch and his people is extended to all those who, through the cleansing power of the atonement “after all [they] can do,”106 prepare themselves to receive it.107 “For this is Zion—the pure in heart”108—and we are specifically told that the reward of the pure in heart is that they shall “see God.”109]

Therefore, sanctify yourselves that your minds become single to God, and the days will come that you shall see him; for he will unveil his face unto you, and it shall be in his own time, and in his own way, and according to his own will. Remember the great and last promise which I have made unto you.[110]

Figure 8. Eugène Carrière, 1849-1906: Intimacy, or The Big Sister, ca. 1889.

The supreme qualification signaling readiness for this crowning blessing is charity, what Nibley calls the “essence of the law of consecration …, without which, as Paul and Moroni tell us, all the other laws and observances become null and void.[111 Love is not selective, and charity knows no bounds.”112 Thus “if I expect anything in return for charity except the happiness of the recipient, then it is not charity.”113 For in charity, Nibley continues, “there is no bookkeeping, no quid pro quo, no deals, interests, bargaining, or ulterior motives; charity gives to those who do not deserve and expects nothing in return; it is the love God has for us, and the love we have for little children, of whom we expect nothing but for whom we would give everything.”114]

Conclusions

The five celestial laws are impressively laid out for us in the text of Moses 5-8. The stories interwoven with these laws make it absolutely clear what kind of results can be expected for individuals and societies as they keep or break divine covenants.

Remarkably, these laws, along with the “offices of Peter, James, and John”[115 through which they have always been given, were described in the Book of Moses and others of Joseph Smith’s early revelations116 more than a decade before the complete endowment was administered by him to others in Nauvoo. It seems that he knew early on much more about these matters than he taught publicly, problematizing the view that the temple endowment was simply an invention of the final few years of his life.117]

This essay is adapted from Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. Temple Themes in the Book of Moses. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2014. English: https://archive.org/details/150904TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses2014UpdatedEditionSReading ; Spanish: http://www.templethemes.net/books/171219-SPA-TempleThemesInTheBookOfMoses.pdf, pp. 203–216. For a more complete discussion of temple texts in the context of wider scholarship on temple theology, see J. M. Bradshaw, Book of Moses as a Temple Text.

Notes on Figures

Figure 1. Public Domain, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ghent_Altarpiece_A_-_Cain_-_Abel_-_sacrifice.jpg. Original in the Cathedral of St. Bavon at Ghent, Belgium.

Figure 2. Figure © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Figure 3. Photograph IMG_0038, 23 November 2009, © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Figure 4. Photograph sheep-Xxx, 9 April 2000, © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Figure 5. Photograph IMG_0217, 16 January 2009, © Jeffrey M. Bradshaw.

Figure 6. Mural in the Serbian Orthodox Monastery Viktor Dečani, situated in Kosovo and Metohija, twelve kilometers south of the town of Pec. © Blago Fund, Inc. https://www.blagofund.org/Archives/Decani//Church/Pictures/Fresco_Collections/Genesis/CX4K2236.html (accessed July 8, 2021)

Figure 7. Zsuzsanna Gulácsi, Mani’s Pictures: The Didactic Images of the Manichaeans from Sasanian Mesopotamia to Uygur Central Asia and Tang-Ming China. Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies 90. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2015. Detail of image on p. 439. For a discussion of this painting in relation to the Book of Moses account of the gathering of the righteous to Zion and their eventual ascent to the presence of God, see J. M. Bradshaw, Moses 6–7 and the Book of Giants, 1123–33, 1143–46.

Figure 8. Public Domain, https://www.fulcrumgallery.com/Eugene-Carriere/Intimacy-Also-Called-The-Big-Sister-1889_830836.htm.

References

Alter, Robert, ed. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 2004.

Andrus, Hyrum L. Doctrinal Commentary on the Pearl of Great Price. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1970.

Barney, Kevin L. "Poetic diction and parallel word pairs in the Book of Mormon." Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 2 (1995): 15-23.

Benson, Ezra Taft. 1977. A vision and a hope for the youth of Zion (12 April 1977). In BYU Speeches and Devotionals, Brigham Young University. https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/ezra-taft-benson/vision-hope-youth-zion/. (accessed August 7, 2007).

———. The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1988.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Jacob Rennaker, and David J. Larsen. "Revisiting the forgotten voices of weeping in Moses 7: A comparison with ancient texts." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 2 (2012): 41-71. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/revisiting-the-forgotten-voices-of-weeping-in-moses-7-a-comparison-with-ancient-texts/. (accessed June 2, 2021).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/download/140123IGIL12014ReadingS.

———. "The LDS book of Enoch as the culminating story of a temple text." BYU Studies 53, no. 1 (2014): 39-73.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014. https://archive.org/details/151128TempleThemesInTheOathAndCovenantOfThePriesthood2014Update ; https://archive.org/details/140910TemasDelTemploEnElJuramentoYElConvenioDelSacerdocio2014UpdateSReading. (accessed November 29, 2020).

———. "Freemasonry and the Origins of Modern Temple Ordinances." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 15 (2015): 159-237. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/freemasonry-and-the-origins-of-modern-temple-ordinances/. (accessed May 20, 2016).

———. "What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?" In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1-144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016. http://www.jeffreymbradshaw.net/templethemes/publications/01-Bradshaw-TMZ%203.pdf.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and K-Lynn Paul. "“How thankful we should be to know the truth”: Zebedee Coltrin’s witness of the heavenly origins of temple ordinances." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 21 (2016): 155-234. www.templethemes.net. (accessed January 23, 2017).

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "Faith, hope, and charity: The ‘three principal rounds’ of the ladder of heavenly ascent." In “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson, 59-112. Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/faith-hope-and-charity-the-three-principal-rounds-of-the-ladder-of-heavenly-ascent/.

———. "The Book of Moses as a Temple Text." In Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses: Inspired Origins, Temple Contexts, and Literary Qualities, edited by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David R. Seely, John W. Welch and Scott Gordon, 421–68. Orem, UT; Springville, UT; Reading, CA; Toole, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, Book of Mormon Central, FAIR, and Eborn Books, 2021.

———. "Moses 6–7 and the Book of Giants: Remarkable Witnesses of Enoch’s Ministry." In Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses: Inspired Origins, Temple Contexts, and Literary Qualities, edited by Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David R. Seely, John W. Welch and Scott Gordon, 1041–256. Orem, UT; Springville, UT; Reading, CA; Toole, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, Book of Mormon Central, FAIR, and Eborn Books, 2021.

Bruner, Frederick Dale. 1990. Matthew: A Commentary. 2 vols. Vol. 2: The Churchbook. Revised and Expanded ed. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2004.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, A Cultural Biography of Mormonism’s Founder. New York City, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1949. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Vol. 2: From Noah to Abraham. Translated by Israel Abrahams. 1st English ed. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, The Hebrew University, 1997.

Clark, J. Reuben, Jr. "Talk for the Evening Meeting." In Conference Report: One Hundred Twelfth Semiannual General Conference, October 1942, 54-59. 1942.

Dahl, Larry E., and Charles D. Tate, Jr., eds. The Lectures on Faith in Historical Perspective. Religious Studies Specialized Monograph Series 15. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1990.

Draper, Richard D., S. Kent Brown, and Michael D. Rhodes. The Pearl of Great Price: A Verse-by-Verse Commentary. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Duke, James T. "Word pairs and distinctive combinations in the Book of Mormon." Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 32-41.

Eyring, Henry B., Jr. "That we may be one." Ensign 28, May 1998, 66-68.

Faust, James E. ""Who shall ascend into the hill of the Lord?"." Ensign 31, August 2001, 2-5.

Freedman, David Noel. The Nine Commandments. Des Moines, IA: Anchor Bible, 2000.

———. "The nine commandments." Presented at the Proceedings of the 36th Annual Convention of the Association of Jewish Libraries, La Jolla, CA, June 24-27, 2001. http://www.jewishlibraries.org/ajlweb/publications/proceedings/proceedings2001/freedmand.pdf. (accessed August 11, 2007).

Hales, Robert D. Return: Four Phases of Our Mortal Journey Home. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010.

Hamilton, Victor P. The Book of Genesis: Chapters 1-17. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1990.

Hinckley, Gordon B. Teachings of Gordon B. Hinckley. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book Company, 1997.

Johnson, Mark J. "The lost prologue: Reading Moses Chapter One as an Ancient Text." Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 145-86. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/the-lost-prologue-reading-moses-chapter-one-as-an-ancient-text/. (accessed June 5, 2020).

Kass, Leon R. The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis. New York City, NY: Free Press, Simon and Schuster, 2003.

Kren, Emil, and Daniel Marx. n.d. The Ghent Altarpiece: The offering of Abel and Cain. In Web Gallery of Art. http://www.wga.hu/frames-e.html?/html/e/eyck_van/jan/09ghent/1open1/u2cain.html. (accessed August 26, 2006).

Lee, Harold B. The Teachings of Harold B. Lee. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1996.

Malan, Solomon Caesar, ed. The Book of Adam and Eve: Also Called The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan: A Book of the Early Eastern Church. Translated from the Ethiopic, with Notes from the Kufale, Talmud, Midrashim, and Other Eastern Works. London, England: Williams and Norgate, 1882. Reprint, San Diego, CA: The Book Tree, 2005.

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. "The Book of Giants (4Q203)." In The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, edited by Florentino Garcia Martinez. 2nd ed. Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson, 260-61. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1996.

McConkie, Bruce R. Mormon Doctrine. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

———. "Obedience, consecration, and sacrifice." Ensign 5, May 1975, 50-52.

McKay, David O. Cherished Experiences from the Writings of David O. McKay. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1955.

———. Treasures of Life. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1962.

Mika’el, Bakhayla. ca. 1400. "The book of the mysteries of the heavens and the earth." In The Book of the Mysteries of the Heavens and the Earth and Other Works of Bakhayla Mika’el (Zosimas), edited by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1-96. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1934. Reprint, Berwick, ME: Ibis Press, 2004.

Nibley, Hugh W. Enoch the Prophet. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 2. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986.

———. "On the sacred and the symbolic." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 535-621. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994. Reprint, Nibley, Hugh W. “On the Sacred and the Symbolic.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 340-419. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

———. "Assembly and atonement." In King Benjamin’s Speech: ‘That Ye May Learn Wisdom’, edited by John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks, 119-45. Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998. Reprint, Nibley, Hugh W. “Assembly and Atonement.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 420-444. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

———. "Abraham’s temple drama." In The Temple in Time and Eternity, edited by Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks, 1-42. Provo, UT: The Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999. Reprint, Nibley, Hugh W. “Abraham’s temple drama.” In Eloquent Witness: Nibley on Himself, Others, and the Temple, edited by Stephen D. Ricks. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 17, 445-482. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2008.

———. 1954. "The ancient law of liberty." In The World and the Prophets, edited by John W. Welch, Gary P. Gillum and Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 3, 182-90. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1987.

———. 1967. Since Cumorah. 2nd ed. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 7. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), 1988.

———. 1975. "Zeal without knowledge." In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 63-84. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1980. "How firm a foundation! What makes it so." In Approaching Zion, edited by D.E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 149-77. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1982. "The prophetic Book of Mormon." In The Prophetic Book of Mormon, edited by John W. Welch. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 8, 435-69. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1984. "We will still weep for Zion." In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 341-77. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1985. "Scriptural perspectives on how to survive the calamities of the last days." In The Prophetic Book of Mormon, edited by John W. Welch. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 8, 470-97. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

———. 1986. "The law of consecration." In Approaching Zion, edited by Don E. Norton. The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley 9, 422-86. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1989.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., ed. 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1-36; 81-108. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2001.

Oaks, Dallin H. "The challenge to become." Ensign 30, November 2000, 32-34.

Packer, Boyd K. The Holy Temple. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980.

Peterson, Daniel C. "On the motif of the weeping God in Moses 7." In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 285-317. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=11&article=1066&context=mi&type=additional. (accessed September 2, 2020).

Pratt, Parley P. 1853. "Heirship and priesthood (10 April 1853)." In Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. Vol. 1, 256-63. Liverpool and London, England: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1853-1886. Reprint, Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1966.

Sarna, Nahum M., ed. Genesis. The JPS Torah Commentary, ed. Nahum M. Sarna. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989.

Skinner, Andrew C. "Joseph Smith vindicated again: Enoch, Moses 7:48, and apocryphal sources." In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, 365-81. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 2002. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=14&article=1066&context=mi&type=additional. (accessed August 25, 2020).

Smith, Joseph, Jr. 1938. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1969.

Stone, Michael E. "Question." In Armenian Apocrypha Relating to Adam and Eve, edited by Michael E. Stone, 114-34. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1996.

Talmage, James E. 1912. The House of the Lord. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1998.

Taylor, John. The Government of God. Liverpool, England: S. W. Richards, 1852. Reprint, Heber City, UT: Archive Publishers, 2000.

Tvedtnes, John A. "Word Groups in the Book of Mormon." Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 6, no. 2 (1997): 263-68.

Welch, John W. The Sermon at the Temple and the Sermon on the Mount. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1088&context=mi. (accessed July 14, 2020).

———. "The temple in the Book of Mormon: The temples at the cities of Nephi, Zarahemla, and Bountiful." In Temples of the Ancient World, edited by Donald W. Parry, 297-387. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1994.

———. The Sermon on the Mount in the Light of the Temple. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2009.

Westermann, Claus, ed. 1974. Genesis 1-11: A Continental Commentary 1st ed. Translated by John J. Scullion. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1994.

Wise, Michael, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. New York City, NY: Harper-Collins, 1996.

Endnotes

This oft-cited triplet appears to be one of the many stock, fixed distinctive combinations of words “which belonged to the literary tradition of Israel and Canaan, and poets [and prophets], specially trained in their craft, drew on this stock to aid in the… composition of parallel lines.… [These combinations were, figuratively speaking, part of] the poets’ dictionary, as it has been called” (Berlin, cited in J. T. Duke, Pairs, p. 33. See also K. L. Barney, Poetic; J. A. Tvedtnes, Word Groups). Though its equivalent appears only once in the Bible (James 3:15), a combination of these terms in pairs or triplets occurs several times in LDS scripture (Mosiah 16:3; Alma 41:13, 42:10; Doctrine and Covenants 20:20, 29:35; Moses 5:13, 6:49).

For an extensive discussion of temple themes in scripture relating to the doctrine of Christ and the ladder of heavenly ascent (or ladder of virtues), see J. M. Bradshaw, Faith, Hope, and Charity.

For a discussion of the role of Freemasonry in preparing the Saints for the Nauvoo temple ordinances, see J. M. Bradshaw, Freemasonry.

An interesting Essay, but it leaves me wondering why you do not include the law of tithing as one of the “Celestial Laws.”