[Page 63]Abstract: The Book of Mormon has been explained by some as a product of Joseph Smith’s 19th century environment. Advocates of this thesis have argued that the phrase secret combinations is a reference to Freemasonry, and reflects Joseph’s preoccupation with this fraternity during the Book of Mormon’s composition in 1828–29. It is claimed that this phrase is rarely, if ever, used in a non-Masonic context during 1828–29, and that a type of “semantic narrowing” occurred which restricted the term to Freemasonry. Past studies have found a few counter-examples, which are reviewed, but none from during the precise years of interest. This study describes many newly-identified counterexamples, including: anti-Masonic authors who use the term to refer to non-Masonic groups, books translated in the United States, legislature bills, grand jury instructions, and works which so characterize slave rebellions, various historical groups and movements, Biblical figures, and religious groups. These examples are found before, during, and after the critical 1828–29 period. Examples from 1832 onward likewise demonstrate that no semantic shift occurred which restricted secret combination to Masonry. This element of the environmental hypothesis has now been robustly disproven.

Introduction1

I developed my taste for debates in Mormon historiography when, as a teen, I encountered Daniel Peterson’s response to Dan Vogel’s theory that the Book of Mormon included [Page 64]“anti-Masonick” polemic.2 A centerpiece of this debate was the term secret combinations which Vogel argued had a nearly exclusive Masonic connotation following the William Morgan hysteria of 1826. “At the time of the Book of Mormon’s publication,” he wrote, “the term ‘secret combinations’ was used almost exclusively to refer to Freemasonry.”3

Vogel’s account is marred by his persistence in referring to those who differ with him as “apologists.”4 Such writers are not portrayed as having genuine, potentially well-founded differences of opinion about the historical evidence. Instead, one is said to differ with Vogel only because of theological baggage: “Resistance among Mormon scholars to the anti-Masonic interpretation, in my opinion, is theologically, not historically motivated.”5 One wonders how far Vogel would entertain the claim that authors hostile to the Church’s truth claims have theological (or a-theological) luggage of their own which might equally skew their weighting of the historical evidence.6 Furthermore, to characterize D. Michael Quinn’s [Page 65]work as apologetic seems lexically strained, to say the least.7 Quinn is many things, but he is hardly a Mormon apologist, save in the sense that all authors — including Vogel — are apologists. That is, they provide a reasoned defense of their thesis regarding a given question.8 Vogel’s loaded terminology seems yet another example of those who dispute the Church’s truth claims portraying themselves as “objective,” “scholarly,” and “historical,” while those who differ are merely theologically motivated, intellectually dishonest “apologists.”9 [Page 66]Even as a callow youth, I was immediately suspicious of Vogel’s theory because of the difficulty in proving a negative. No one contests the fact that the term secret combinations could be and was applied to the Masons — but Vogel’s language parallel is compelling only if there is scant use of the term in a non-Masonic context in Joseph’s era. Peterson reported that Vogel and Brent Metcalfe later claimed “that the phrase ‘secret combination’ was never used at the time of the translation and publication of the Book of Mormon, except to refer to Freemasonry.”10 Vogel replied:

What I said was that after extensive reading in the primary pre-1830 sources, I had been unable to find another use for the term and doubted that one would be found. I remain skeptical, but wisdom dictates that the door be left open slightly in case someone on the margins of popular nineteenth-century culture happened to have used the term in a non-Masonic context.11

This seems to me a significant potential flaw, or at least reason for caution — I am leery of theories that rely solely on negative evidence (such as the claim that something never appears in print), especially when counter-evidence is difficult to access.12 I suspect Vogel has read far more early 19th century primary sources than I have — and so, who am I (or most readers) to gainsay him? But, on the other hand, how exhaustive can his — or anyone’s — search really have been? [Page 67]

Past Efforts to Disprove the Negative

Some authors have attempted to undermine Vogel’s thesis in part by locating uses of secret combinations from prior to the anti-Masonic panic of 1826 or uses which post-date the panic which clearly refer to something besides Masonry. Early on, Daniel Peterson understood the necessity of a search of the primary sources:

What is needed, before we can confidently declare that the phrase “secret combination” was never used in non-Masonic contexts in the 1820s and 1830s, is a careful search of documents from that period of American history that have nothing to do with the controversy surrounding the Masons. This has not yet been done. Nevertheless, there is good reason already to predict that such a survey would not support Vogel’s claim.13

Peterson reported on 10 instances of the phrase secret combinations located by John Welch via “a search of those nineteenth-century federal and state court opinions available on computer.”14 Peterson’s finds were, admittedly, less than ideal for resolving the issue, since his earliest example dated to 1850: “I can only sadly agree that the laborious task of combing the unindexed and noncomputerized legal and other records of the first half of the nineteenth century remains to be done.”15 Despite these limitations, Peterson predicted that “the apparently widespread use of the phrase ‘secret combinations’ … leads me confidently to expect that the phrase was common in the earlier period as well.”16 (His optimism was rewarded [Page 68]when, two years later, he found an example from 1826 that applied the term to Andrew Jackson in a non-Masonic context.17) Vogel would dismiss this evidence, agreeing with D. Michael Quinn that

Given the possible “sarcastic use of an anti-Masonic phrase by one Freemason against another,” … Jackson’s 1826 letter “does not support Peterson’s claim that the letter ‘definitively’ disproves all claims for the exclusively anti-Masonic use of the phrase ‘secret combination.’”18

(We note, incidentally, how vulnerable Vogel’s stance is — he must explain away any contrary evidence, for even a few counter-examples weaken his thesis substantially.) Peterson’s prediction was in part borne out by Nathan Oman’s discovery of legal uses of the term combination in cases from the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and two examples of secret combinations in 1819 and 1825.19 “Even if Peterson’s hoped for evidence did exist,” Vogel was quick to reply to Welch’s and Peterson’s legal finds, “Legalese was not the language of Joseph Smith, nor was it the language of his intended audience. It seems fruitless to search legal archives for exceptions to the interpretive rule that clearly dominated Smith’s cultural milieu.”20 Writing later, Oman conceded that “legal writing can be turgid,” and “we should be cautious in generalizing about ordinary language on the basis of legal materials,” but argued that Vogel’s “assum[ption] that all judicial opinions can be dismissed as irrelevant ‘legalese’” is “simplistic.”21 Oman also provided additional examples of secret combinations from the [Page 69]two decades following the Book of Mormon’s publication.22 More recently, Ben McGuire provided details of an electronic database search for the term secret combinations that did not mention mason or freemason, though he did not examine specific quotes in context.23 In 2003, Paul Mourtisen noted of the claims of verbal dependence that “the term secret combinations is more distinctive and deserves closer scrutiny.”24 He contested the strength of the newspaper evidence presented by Vogel and others:

In support of these claims, such authors point to seven occurrences of the term found in four upstate New York newspapers between 1827 and 1829. At first this list may look impressive, but aspects of timing and location do not match up with what we know of Joseph Smith’s whereabouts during the same period. Indeed, on closer examination, it is most unlikely that any occurrences of the term could have directly influenced the Book of Mormon. The first instance of the term secret combination occurred in March 1827 in a newspaper published in Batavia, New York, about 60 miles from Palmyra. Three more instances appeared in Palmyra newspapers in July, November, and December of 1828. At that time Joseph Smith was living not in Palmyra but in Harmony, Pennsylvania, a distance of two or three days’ travel. The remaining three occurrences were published in Palmyra newspapers [Page 70]in September, October, and November of 1829, several months after the translation was completed and the copyright secured and while the printing was under way. Therefore, the argument that Joseph Smith adopted the term from anti-Masonic writings cannot be sustained by these sources. It will stand only if it can be shown that these newspaper articles are representative of a wider range of anti-Masonic writings, yet to be identified, that Joseph Smith might reasonably be expected to have read. But even that idea is a matter of some uncertainty. In 1830 James Creighton Odiorne published a collection of popular anti-Masonic writings entitled Opinions on Speculative Masonry. This 280-page anthology included 29 speeches, sermons, editorials, and letters by various anti-Masonic writers from New York and Massachusetts, most of which had previously circulated in pamphlet form. Yet in this entire collection the term secret combination occurs only once.10 If the term were a generally understood code name for Freemasonry, it is difficult to explain why it is almost absent from a book of this kind.25

Mourtisen went on to present more court documents (50 uses in the 19th century, including six prior to 1850),26 and selections from the Internet and the “Making of America Collection at the University of Michigan and Cornell University.”27 He provides a total of 24 examples (with some overlap from previous studies) from 1709–1850, with at most two references to the Freemasons (1830 and 1835). Unfortunately, there were no uses of the term from the key period of 1826–1830 that did not mention freemasonry (the sole example, from 1830, did mention the fraternity).28 A few of his early examples (e.g., David [Page 71]Hume) come from British works which may be less helpful in evaluating any distinctive patterns in early American usage. I thus find myself as a dwarf straining to peer over the shoulders of giants — but, in this case, the dwarf has a secret weapon: Google Books.

Description of the Current Study

It occurred to me that Peterson’s wish for more digitized records — which I remembered from my first encounter with this issue in 1990 — is now a reality, beyond even the resources available to Mourtisen or Oman. In 2004, web search giant Google began a massive project to digitize 15 million volumes within a decade (and, by April 2013, they had succeeded in scanning twice that).29 Several American and international libraries cooperated in the effort, so a vast variety of publications are now available and searchable through optical character recognition. It is thus almost a trivial exercise to search any range of dates for any textual string, and I did so. I was surprised at the number and variety of uses of secret combination/s between 1750 and 1832. I here report on my findings. I make no claim to have been exhaustive.30 But the present results are sufficient, I believe, to convince all but the most ideologically driven that secret combinations referred to a far broader range of groups than Masonry, both before, during, and after the Morgan panic of 1826. It is simply no longer tenable to claim that this phrase is a clear indicator of Masonic influence or intent on the part of an author in the late 1820s. I will describe three groups of documents: (1) anti-Masonic documents that nevertheless challenge Vogel’s reading; (2) general documents from 1782–1832; and (3) documents treating religious subjects. [Page 72]

Group 1 — Anti-Masonic Usage

To be sure, many examples of the term are available in the anti-Masonic literature. Despite the fairly broad claims sometimes made by Vogel, he elsewhere makes the more restrained claim that “in the context of the 1828 U.S. presidential campaign, the phrase [secret combinations] had become politically charged, not that anti-Masons had invented the phrase.”31 “The term … did not take on its full anti-Masonic meaning until 1827–28.”32 Thus, the most probative evidence, in Vogel’s view, would involve the late 1820s and early 1830s. I will call this period, during which Vogel hypothesizes a semantic narrowing to refer only to Masons, the “anti-Masonic watershed.” (We recall that the gap in examples provided by Mourtisen occurs in precisely this range of dates — a good example of how the contingent nature of which documents are available for digital searching can impact the dataset.) What is intriguing, however, is that even some of the anti-Masonic usage during the watershed makes it clear that secret combinations does not refer to Masonry exclusively. Not only do the authors use the phrase to refer to freemasonry, but they continue to use it to apply to other groups as well — which is the exact opposite of what we ought to see if the anti-Masonic press converted the phrase into one which referred only to the Masons. In one example whose hysteria is typical of the genre, the author suggests that American citizens of 1827 ought to

amend … our constitutions, both state and federal, so that no man should be allowed to hold any office of honour or profit, under them, who would not, in assuming the duties of it, swear to and subscribe a declaration — in addition to the oath or oaths now in use — that he was not then a member[Page 73], and would not thereafter become one of any secret, self-created combination whatsoever.33

As worried as this author is about Masonry, he clearly believes that a wide variety of “secret, self-created combinations” are present and future risks: one should not join “any … whatsoever.” He appeals to Washington’s farewell address, claiming that the first president urged his countrymen to “beware of SECRET ASSOCIATIONS, under whatever plausible character.”34 The anti-Masonic author then goes on to ask, “When we hear him [Washington] uttering a farewell warning to his countrymen, to BEWARE of SECRET COMBINATIONS, what are we to suppose he means?… What secret combination existed in our country at that time, except Masonry?”35 Vogel cites a similar example, also from 1827, which asks “Do not these words [of Washington’s] … point with an index that cannot be mistaken, to the society of Freemasons?”36 Vogel then argues that since the “Anti-Masons had … expanded on Washington’s own words [by adding secret to combination]37 to make it appear that he agreed with them,” this implies that “[I]n such an environment, the Book of Mormon’s use of the phrase [Page 74]would have been understood as an unmistakable reference to Freemasonry.”38 But, the example which I introduce above undercuts this view — in my example, the anti-Masonic author adds the word secret to both of Washington’s terms: combinations and associations. Are we to conclude, then, that secret associations was another code word for Masonry? It would appear not, because the author insists that there were not any other secret combinations in Washington’s era, so Washington must have meant the Masons — but his need to make such a claim is implicit evidence that the phrase secret combination was already broadly understood by his audience to apply to any of a number of nefarious organizations or practices. For the anti-Masonic polemic to succeed, then, the author must make the more general warning from Washington (a Mason) apply only to Masonry. But he does not do this by putting a term that “everyone knows” means the freemasons in Washington’s mouth, instead, he uses the term, and then insists that there were no other candidates for this group but the freemasons. The anti-Masonic political parties likewise provide evidence for the proposition that secret combinations did not apply uniquely to Masonry. The Connecticut state convention reported one resolution in 1830, well-after Vogel’s anti-Masonic usage is supposed to have been established:

Resolved That all secret “combinations of men under whatsoever plausible character,”39 have a direct tendency to control and to counteract the regular deliberations and actions of the constitutional authorities. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force, and to put in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will — [Page 75]of a small, but oftentimes, artful and enterprising minority of the community.40

Once again we see a tacit acknowledgement that the term has a much broader meaning than Masonry, since “all secret combinations,” regardless of how “plausible” they may appear, are a threat to liberty. Such a declaration would be pointless if secret combination was not understood to have a much broader application. And, all such groups will be repudiated by those who reject Masonry:

This principle, political Antimasonry, induces men to study; it brings home to the voters of our country, the question of the tendency of secret societies: and when that question is understandingly put, they will decide against the mystic brotherhoods of every name, with overwhelming majorities. 41

In 1830 — well after both the watershed and the dictation of the Book of Mormon — a fourth anti-Masonic work wrote:

The Jesuits were a secret combination of men. It was this “which principally contributed to extend their power.” Their pernicious influence in society was extended and prolonged by the means of their secret compact. Herein is seen, the dangerous tendency of secret societies in a community. It has been the same principle of secret combination, which has extended and prolonged the power and pernicious influence of Freemasonry.42

[Page 76]Here the Jesuits — a Catholic religious order — are characterized as a secret combination, and used as an illustration to help the reader appreciate the threat of another secret combination: freemasonry. But this occurs at least two years after Vogel has told us that the anti-Masonic usage was established and exclusive, demonstrating that even among anti-Masonic authors, the usage wasn’t exclusive at all. Also in 1830, an anti-Masonic state convention discussed a

committee appointed…for the sole purpose of diffusing information extensively on the subject of freemasonry, and other secret combinations against [Page 77]the equal rights of mankind and our free institutions. … …the great object of this convention is, to eradicate the evils of freemasonry, and other secret societies. To effectuate this purpose, information of the nature, tendency, and principles of all secret societies, but especially of the masonic institution, must be laid before the world. … All that has been said against freemasonry, will apply, to a certain extent to all secret societies. They are dangerous to all governments, but especially to those that are free. 43

Freemasonry is, quite simply, only one of many “other secret combinations,” which functions as a synonym for “secret societies.” This convention likewise resolved that “a Committee of correspondence be appointed, whose duty it shall be to correspond…for the purpose of diffusing information on the subject of freemasonry, and other secret combinations against the equal rights of mankind, and our free institutions. …”44 Another committee was

to report what measures can constitutionally and properly be used, to effectuate the extinction of freemasonry; to guard against its revival; and to secure our free institutions against the future insidious assaults of all secret societies. … diffusing information extensively on the subject of freemasonry, and of other secret combinations, against the equal rights of mankind and our free institutions.45

Those who early resisted freemasonry were lauded, since “There are few men in any age, who, at a time like that, and surrounded as they were, would not have shrunk back from the impending responsibility of their situation. They stood isolated and alone. There were no surrounding combinations to cheer and sustain them in their course.”46 Thus, even a hypothetical group arrayed in opposition to freemasonry might well be a combination — though presumably not a “secret” one. Clearly, secret combination had a much broader lexical range than Vogel has been willing to grant, even among anti-Masonics, even after 1827–28. And this usage ranges smoothly from the anti-Masonic movement’s early days, through the period of the Book of Mormon’s translation, and afterward. [Page 78]

Group 2 — Use in General Publications in the United States

The anti-Masonic literature thus supports Peterson’s and Oman’s view that secret combinations was a broad term in general use before, during, and after the Book of Mormon’s publication. I have located several examples of American writing unrelated to freemasonry which reinforce this conclusion. A bill passed in New Jersey in 1782 read, in part:

And whereas, in order the more effectually to carry their insidious and pestilent Machinations into Effect, our said internal Enemies, still flattering themselves with the Hopes of ultimately reducing these United States to the absolute Sway and Dominion of Great-Britain by their clandestine Practices and secret Combinations against their native Country, have justly alarmed the Apprehensions of our well-affected and patriotick [sic] Citizens, and have more especially excited their Jealousy by giving Reason to suppose they are aiming to introduce some of their own Faction into the Legislature, and into Posts of Trust, Profit and Influence.47

This description of “Internal Enemies,” attempting to reduce the nation “to the absolute Sway and Dominion” of a political rival, through a “Faction” seeking “Posts of Trust, Profit, and Influence” via a secret combination, is paralleled precisely by the Book of Mormon’s Gadianton band. Perhaps Joseph was cribbing from the New Jersey statute book?48 Or, perhaps he had reference to a Virginia grand jury address in 1789:

[Page 79]Our next care, gentlemen of the grand jury, will be to watch the motions of our internal enemies; to anticipate their various intrigues; and to disappoint those secret combinations, into which they may have entered. … Some men feared the losing of that influence, they had assumed and established to themselves, under the weak and divided government of the several states: some again apprehended, that they would be deprived of the benefits and emoluments of certain lucrative offices.49

In 1806, a New York newspaper discussed “The Kentucky Association, Blount’s Conspiracy and General Miranda’s Expedition,” declaring that “in the history of conspiracy and secret combinations, of those which have affected the United States, there are none of so extraordinary a nature, as the three above mentioned.”50 These machinations aimed to, respectively: separate Kentucky and parts of the west from the United States and join them to the British crown; recruit men from the United States, and invade Spanish territory from British Canada, hoping to annex it for England; and invade Spanish Venezuela with British encouragement. (Miranda was a Freemason, but no mention of that connection occurs.51) [Page 80]A work from 1804–1807 describes a crisis during President Washington’s second term:

[In 1793] the seditious and violent resistance to the execution of the law imposing duties on spirits distilled within the United States, had advanced. … On the part of the Executive, this open defiance of the laws, and of the authority of the government, was believed imperiously to require, that the strength and efficacy of those laws should be tried. … Meanwhile, the insurgents omitted nothing which might enlarge the circle of disaffection. … a vast mass of opposition remained, determined to obstruct the re-establishment of civil authority. … But although no direct and open opposition was made, the spirit of insurrection was not subdued. … [Thus we see that] when the mind, inflamed [sic] by supposititious dangers, gives a full loose to the imagination, and fastens upon some object with which to disturb itself, the belief that the danger exists seems to become a matter of faith. …Under a government emanating entirely from the people, and with an administration whose sole object was their happiness, the public mind was violently agitated with apprehensions of a powerful and secret combination against liberty, which was to discover itself by the total overthrow of the republican system. That those who were charged with these designs were as destitute of the means, as of the will to effect them, did not shake the firm belief of their existence.52

[Page 81]The citation above comes from the 1832 edition, and its use of secret combination shows no awareness of a lexical shift, though we cannot say whether such a detail would have been noticed or corrected prior to reprinting. Nor are such secret combinations even confined to the political realm. In 1818, the governor of Connecticut urged that limited liability partnerships be publicly registered to avoid secret combinations unknown to the public:

On these grounds, I respectfully invite you to consider, whether it is not contrary to public policy, if not an abridgement of private right, to restrain individuals from forming partnerships with a limited responsibility. As the community are interested in being guarded against frauds arising from secret combinations, it would be proper to require contracts of this nature, to be recorded in a public office.53

This is not, by any stretch of the imagination, Freemasonry. A potential uprising among southern slaves was characterized as due to a secret combination in an 1822 work:

Although the utter impracticability of effecting any permanent change in their condition, by an insurrection among our Slaves, has been, we think, fully demonstrated, it is nevertheless indispensible to our safety to watch all their motions with a careful and scrutinising eye — and to pursue such a system of policy, in relation to them, as will effectually [Page 82]prevent all secret combinations among them, hostile to our peace.54

In 1828–29, almost contemporaneously with the Book of Mormon’s production (and well after the watershed), one author cited a work which described the Hetaria, a Greek group dedicated to resistance against the Ottoman Turks:

One hundred dollars was paid by each member [of the Hetaria] on admission, which was… kept by… [the] invisible government. Every facility was given for admission, and, like the Carbonari, any one member could constitute another, by calling a third as witness. This did not so much endanger the secrets of the society as might be supposed. … The society spread most rapidly: thousands became members, in the southern parts of Russia, and in the various kingdoms of Europe. … But the Hetaria did not rely solely upon the zeal and voluntary exertions of individual members; certain ones were selected, and sent forth by the governors of the society, not only to make proselytes, but to keep awake the hopes of the people.

Having quoted this material, the reviewer then concludes: “The nature of this association has not, we believe, been heretofore given so fully to the public, and it merits the attention of those who are not aware of the full effect of secret combinations, which sometimes promote a good cause, and not unfrequently increase the mischief of bad ones.”55 Not only are clandestine Greek nationalists a secret combination but for the author such [Page 83]groups might support good or evil causes (unlike the view of the anti-Masonic authors, for whom any secret society is cause for alarm). This stands as a rebuke to Vogel’s claim that following the watershed, secret combinations was an exclusively anti-Masonic slur. Further, in an 1831 biographical encyclopedia, it is reported that

Jahn first conceived the idea of making gymnasia [German] national establishments for education. … [I]n 1814, Jahn reopened his institutions, and exerted all his powers again to make them schools of patriotism. In the meantime, the liberal spirit which spread over the continent of Europe, found its way into the gymnasia. The German government began to dread the effects of that love of freedom in the nation. … After the murder of Kotzebue, by the student Sand, the government fearing or professing to fear the existence of secret combinations of a political character in the gymnasia, Jahn and many of his friends were arrested.56

We see yet again that secret combinations may be “of a political character,” but such a qualifier implies that they need not be. Again we see no sign of the freemasons. We see no sign of the watershed in an 1832 report to a Methodist meeting on difficulties with book publishing:

Indeed, it is proper to mention here, that your present agents have been under the necessity of encountering a competition on the part of certain other publishers, of a character unparalleled in all our former history; and attempts, in fact, by secret combinations and base artifices, to supplant, and [Page 84]even crush the institution instrusted [sic] to our management.57

A cabal of publishers is not freemasonry, even well after the purported anti-Masonic watershed.

Group 3 — Religious Works

Might a religious work such as the Book of Mormon use the term secret combination in a way utterly unconnected with Masonry during this period? I have found four examples of precisely this. The first is from 1814, published in both England and the United States. It demonstrates a decidedly non-Masonic usage. In a commentary on Judges 3:19, we are told:

Ehud had ingratiated himself with Eglon by the present, and he had no suspicion of one whom he supposed unarmed; and it is likely he expected some information concerning state affairs, or the secret combination of his countrymen: yet he was strangely infatuated to trust himself alone with an Israelite!58

Thus, pre-Davidic kingdom Israelites could be engaged in a secret combination against Moabite overlords. A second example comes from a New York newspaper in 1831 — the precise state, time period, and media in which Vogel has insisted that secret combinations refers only to Masonry. In it, we read:

Dr. Ely says — ”We question the expediency of secret sessions of the Senate of the United States and all [Page 85]other legislative, executive, and judicial assemblies.” — Will the D. please to add, eclesiastical? [sic] If Dr. E. is opposed to all secret combinations, will he please to divulge a few more of the secrets of the orthodox church?59

This ironic aside not only equates secret combinations with a religious group, but also extends the idea to secret meetings of the Senate or any other political body. Such a barb falls flat if everyone understands secret combination to refer only to freemasonry. The third example narrows the time frame even further. It dates from 1828: after the watershed and almost contemporaneous with the Book of Mormon’s production. In a discussion concerning the fate of deceased souls, we read:

[Judas] was admitted among the disciples; was a devil, or a spy from the beginning: if he had known any secret combination among Christ and his disciples, he no doubt would have been brought forward on the trail of Jesus as a witness, for the Jews could not find proof against him.60

Vogel’s thesis would require us to see this as an oblique reference to potential freemasonry among the first century apostles — a decidedly tortured reading. Instead, it seems simplest to admit that this is more solid evidence that secret combination was a term of general use with a wide spectrum of potential applications, political and otherwise. A fourth example — an 1831 volume translated in Andover, Massachusetts, and published in both New York and Andover — says of Jesus:

[Page 86]When brought before Pilate, [Jesus] was not accused of having formed a secret conspiracy. … [Judas] gave them no information respecting his [Jesus’] being engaged in secret combinations. Had this faithless wretch known anything of the kind, or even suspected that Jesus had been able to form secret plans. …had his master been connected with any private associations, would it have been possible for him not to have discovered it? … Moreover the conduct of Jesus … is altogether dissimilar to that of those who have founded secret associations. … A man who forms secret societies … is reserved and must be so. … We all know with what caution those proceed, who are in search of members for a secret Society … before … admitting [one] into important mysteries. … There are many private societies in silent Operation … yet none of them would bid such men as the apostles…a very hearty welcome to their fraternities. … The closer, therefore, we scrutinize whatever Jesus said and did, the more we discover in his conduct entirely at variance with the conjecture, that he founded a secret order, and intended to use it as the means of operation. … Jesus never intended to put the hidden springs of a secret society in motion.(emphasis added)61

The term secret combination is again used to describe a politically subversive possibility regarding Jesus’s ministry — but it is also telling that the author includes a number of synonyms: secret conspiracy, secret plans, private associations, secret associations, secret society (three times), important mysteries, private society, fraternity, and secret order. And, [Page 87]significantly, this serves as an example of secret combination being used in English translation soon after the Book of Mormon’s translation. One is reminded of Vogel’s insistence that “Joseph Smith was aware of the Masonic connotation, and his use of the phrase [secret combinations] was clearly intentional.”62 It is not clear how he knows what Joseph’s intentions were — this seems a conclusion driven by his thesis, and not independent evidence for it. Vogel offers eight alternative, “less problematic words,” that Joseph

could have used … had he wanted to avoid misunderstanding: secret societies, secret alliances, … secret leagues, confederacies, plots, conspiracies, schemes, or clandestine activities. It was not necessary to use the specific phrase “secret combinations.” Obviously, Smith used the term to convey the meaning and comparison he intended.63

This argument is circular, since it must assume that secret combination had the exclusive meaning that Vogel attaches to it. We have seen that this is not the case, and so his claim begs the question of what Joseph intended. Further, for Vogel’s putative alternatives to be superior, he would also have to demonstrate that these terms were commonly used in the early 19th century without referring to Masonry. If not, had Joseph chosen a different word, Vogel could protect his thesis by claiming that the alternative phrase also referred to Masons. As we have seen, many contemporaries (and even anti-Masonic authors) believed there were secret combinations that had nothing to do with Masonry. Perhaps that is what Joseph intended? One can always think of alternatives, but the choice of secret combinations seems natural in its time and place for Masonic and non-Masonic conspiracies. The final text above uses nine synonyms for secret combination (some in common with Vogel’s supposedly less-loaded words). If Vogel’s terms [Page 88]could all avoid referencing Masonry in Joseph’s New York book in 1829, then so can all the terms used by another New York book in 1831: including secret combinations. Further, in just the anti-Masonic works cited herein, the label “secret societies” is used six times. A determined apologist for the environmentalist thesis — such as Vogel — could doubtless turn that commonality into evidence for the Masonic connection if Joseph had chosen to use it instead. Vogel’s decision to leave “the door … open [only] slightly”64 for counter-evidence to his hypothesis would seem to evince a deficient anticipation of what the unexamined evidence might teach us.

Continued Non-Masonic Usage of the Term Beyond 1832

Ben McGuire’s examination of Rick Grunder’s Mormon Parallels also deals at some length with the question of secret combinations.65 While Grunder (unlike Vogel) concedes that some non-Masonic usages of the terms can be found, he insists (like Vogel) that there was a semantic narrowing of the term following the Morgan panic. Over time, he claims, secret combinations came to refer only to Masonry, just as chauvinism refers today only to those opposed to women’s equality.66 As we have seen above, this is not consistent with the data up to 1832. Far from there being a semantic narrowing, secret combinations continued to refer to a large number of groups, and even some anti-Masons made it clear that Masonry was [Page 89]only one example of such a secret combination. It is worth considering some examples from a later period simply to demonstrate that the claimed semantic narrowing did not occur. One particularly intriguing example exists from 1839, in which the author uses the word, and then clarifies that he is not referring to freemasonry, before going on to apply it to the group he addresses:

Distinction, when honorably pursued, may lead to worthy ends; but when secret combinations are made the avenues of pursuit, the end itself can hardly be generous and highminded which demands such means. It is not masonry to which we refer, but to its mimic embryos as existing in this institution. We object not to secrecy itself. It is often a virtue, and the guarding of virtue and peace. But when it is made the shield of vice, the covering for those combinations that originate in selfishness, and scruple not at means, that foster the worst of passions to gain narrow or iniquitous ends — secrecy then is wrested from its legitimate purpose, and deserves the reprehension of the high minded and the virtuous. It is to counteract and expose the abuses of these combinations that we have organized this association, convinced of the extreme necessity of opposing a barrier to the fearful inroads of corruption and vice, through the channels of these secret convivial clubs. … What must we expect when young men in our colleges esteem it an honor, and regard themselves as upon the acme of human glory, can they obtain an initiation into mysteries as profound undoubtedly as were the magic arts by which St. Patrick exterminated toads and snakes from Ireland? … Do these secret associations invigorate talent and strengthen the mind? … These secret clubs are influenced by a contemptible ambition. They regard themselves as a nucleus [Page 90]around which they make every possible effort to concentrate all the honors of the College; watch with suspicion and jealousy the movements of each other and of those not connected with them. Arrogating to themselves such privileges, they sunder the ties of friendship, and create distinctions regardless of merit and moral worth. … Conviviality, self-aggrandizement and the show of friendship, are prominent characteristics of these combinations. The hours of study, sometimes termed tedious, are too often wasted in idle gossip or worse dissipation.67

He thus invokes the known application of the term to freemasonry, only to turn it against his audience and insist that what they are doing is likewise a secret combination. Such a rhetorical strategy is bootless if secret combination has been narrowed to mean masonry, and only masonry. The author concludes his oration by pleading that “our mutual efforts shall conspire to aid and prosper this enterprize [sic], secret combinations shall cease in ‘Old Union’ [College].”68 If this were the only example, it might be offered in support of the idea that lexical narrowing had occurred — one could see the disclaimer as evidence that the phrase always means freemasonry. But, there are multiple other examples which precede and predate it with no caveat or qualification about Masonry at all, which lends support to my view that this usage is a rhetorical flourish (and, as the reader of the entire address will discern, this is an oration full of classical allusions and Ciceronian spunk). I provide several additional examples of non-Masonic references to secret combinations from 1833–1850 in Appendix I. [Page 91]The variety and number of uses seem sufficient to disprove the semantic narrowing hypothesis.

Uses in Great Britain

My search also turned up a number of British works. These are obviously less probative regarding American usage, but they serve as additional witness that the phrase secret combination had a long history in English writing and thought, and shows no sign of lexical narrowing as claimed by Vogel and Grunder. Given the obvious affinities between British and early American thinkers and literary culture, this provides added evidence of how the term was used. Representative examples, by no means exhaustive, are found in Appendix II.

Conclusion

The picture is clear. We now have access to a much broader range of texts than the legal works available to previous researchers, though I have not here exhaustively examined all those that are presently available. It is obvious, however, that even anti-Masonic authors applied the term secret combination to any type of oath-bound, secret society, especially those with political designs. American usage also applied the term to British loyalists or sympathizers; the Jesuits; office seekers who benefited from the weak pre-Constitutional state governments; the Kentucky Association; Blount’s conspiracy; Miranda’s expedition; slave rebellion; 18th-century Greek nationalists; Jesus’s apostles; early Hebrews chafing under their vassalage to Moab; nonpublic meetings of the U.S. Senate; any secret sessions of the legislature, judiciary, or executive branches; the threat of Washington’s government to liquor interests; and the behavior of orthodox religious bodies. Further research may extend these observations, but seems unlikely to disprove them. We also cannot know how representative these texts are — the vagaries of which documents were available for scanning will, of necessity, mean that our perspective remains fragmentary. We have enough [Page 92]fragments, however, to lay Vogel’s expressed view to rest. We have found too many examples, and they cannot all be dismissed as anomalies on the “margins of popular 19th-century culture [which] happened to have used the term in a non-Masonic context.”69 And, Grunder’s more nuanced claim of semantic narrowing is further rebutted by the many post-1832 examples available in Appendix I, in addition to those already identified by Mourtisen.70 At present we do not know which, if any, of the pre-1830 sources were known to Joseph Smith. The most plausible answer to me is that secret combination was no more or less than a common phrase used for any hidden conspiracy or arrangement to one’s benefit, and so Joseph used it to describe the Gadianton group. Vogel seems determined to find an “environmental” influence for every aspect of the Book of Mormon’s narrative (his biography Making of a Prophet is an extended exercise in doing precisely this, with the resulting Joseph madly cutting and pasting influences like a plagiarizing sophomore on a tight deadline). But, given the manifest creativity of the Book of Mormon account, would it not be simpler — and more in keeping with the textual facts presented here — to declare that Joseph invented an oath-bound group, and used a common term for any such group to describe it? When Joseph speaks of a “church,” he need not have had a particular building in New England as a model in mind — why presume that the young man who in a few weeks could dictate the 500+ page Book of Mormon was incapable of concocting a secret society, and just labeling it as such? In any case, to claim that secret combination is a smoking gun which (nearly) always referred to freemasonry in Joseph’s environment or literary culture cannot be sustained by the evidence. Vogel has claimed that the anti-Masonic view has been “long regarded as obvious.”71 The evidence presented here [Page 93]reproves this notion at least in part, and demonstrates why researchers ought to be cautious of matters that seem “obvious.” Obvious connections are rarely questioned or examined critically, and one does not usually seek contrary evidence for propositions that seem self-evident. Yet, they may be mistaken all the same. (Galenic physicians and their patients, after all, used bleeding as a treatment for over two millennia, confident that it “obviously” worked.) If we claim all swans are white, we tend to present each new white swan as if it were evidence. It is, but of a decidedly weak sort. It is far better to seek the single black swan which will disprove a notion — especially if one stumbles across an entire flock. Peterson’s predictions about the use of secret combinations have been robustly confirmed, so perhaps it is appropriate to conclude with his conclusion, which seems even more secure than it was a quarter-century ago:

Dan Vogel’s claim that the phrase “secret combination” (emphasis mine) was used virtually exclusively to refer to Freemasonry at the time of the Book of Mormon’s publication would, if true, be a fact worthy of note. But there is as yet no particular reason to think it true, and considerable reason to doubt it. Vogel’s own evidence … merely demonstrates what has been known for many years, that the phrase was indeed sometimes employed in reference to Masons. But this is a far cry from demonstrating that such was its exclusive use.72

Now that a broader look at the literary culture of the early 1800s is more practical via digital search, Peterson’s skepticism has been vindicated. Before, during, and after Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon, secret combinations was a general term in the United States for any clandestine group or plot, especially one in the political realm. [Page 94]

Appendix I — Uses of Secret Combination in the United States from 1833–1850

I proceed chronologically, with a minimum of commentary and analysis; a heading provides the date of the statement and a brief summary of the person or group(s) characterized as “a secret combination”.

1833, Those working against the interest of those for whom they collect funds:

As no one can coerce in a case like the present but the plaintiff in execution, if he can agree with the officer and indulge at pleasure with the use of the money, because the security is bound, then of all men the security would be the most helpless. Secret combinations or caprice might ruin him.73

1834, French revolutionary patriots:

In the first twelve years of the national administration, the wars of Europe hazarded the peace of the United States. The aggressions of the belligerents, the insolent and seductive character of French enthusiasm, secret combinations, and claims for gratitude, (to revolutionary France,) called for all the firmness, wisdom, and personal influence of Washington.74

1834, American revolutionary patriots:

Thus, on the one hand, the American patriots, by their secret combinations, and then by a daring resolution; and on the other, the British ministers … gave origin to a crisis which eventually produced the dismemberment of a splendid and powerful empire.75 [Page 95]

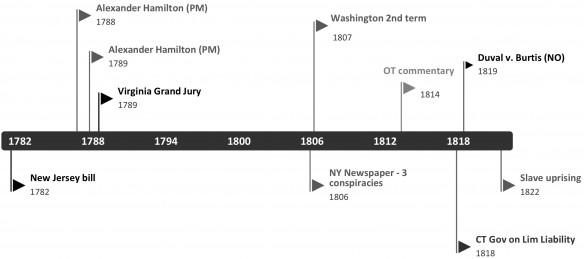

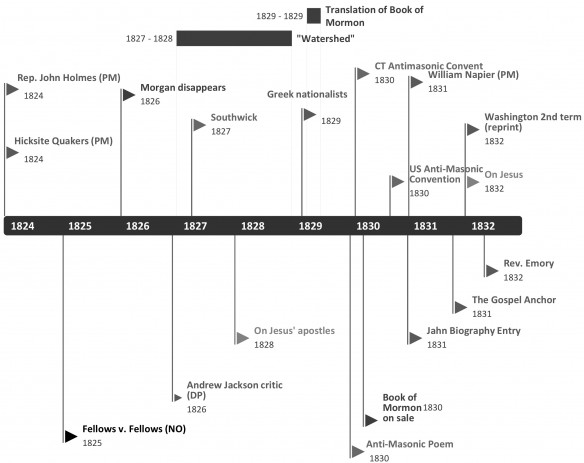

Figures

Figure 1: Uses of secret combination or secret combinations to apply to non-Masonic groups in US publications, 1782–1822. Examples identified previously by Nathan Oman (NO) and Paul Mouritsen (PM) are so labeled.

Figure 2: Uses of secret combination or secret combinations to apply to non-Masonic groups in US publications, 1823–1832. Examples identified previously by Daniel Peterson (DP), Nathan Oman (NO), and Paul Mouritsen (PM) are so labeled.

1835, A supposed “Popish plot”:

Note the use of a Masonic title (‘General Grand High King’) with a mention of secret combination — thus showing that this term could refer to Masonry, while at the same time being used to refer to something else that was also a “secret combination.”

We … can only smile at the religious zeal of its editor, who must be acknowledged to possess some wit, and considerable secretiveness, notwithstanding his declared hostility to all secret combinations. He is, undoubtedly the “General Grand High King” of the anti-Catholic Fraternity.76

1836, Manipulators of the stock market:

Stock-jobbing is the buying and selling of stocks for the purpose of deriving gain from the fluctuations in their prices. And the arts which are resorted to in this business, to “run up,” or to depress stocks, and the secret combinations which are sometimes formed, to control the market and extort money from those who have sold on time, render stock-jobbing, under such circumstances, one of the most hazardous and demoralizing species of gambling.77

1837, Byzantine politics in era of Constantine and Nicholas:

Suspicion and distrust destroyed social confidence — rumors of secret combinations, and dark plots, and threatened violence against the Emperor, excited alarm and apprehension in every mind.78 [Page 97]

1838, German Fem-courts:

Frederick [II] was in conflict with the popes nearly all his life, and was twice excommunicated. … In his time, also, first appeared the most terrific tribunal ever seen on earth, and known by the name of the Fem-courts. … These courts are supposed to have arisen from the total subversion of law and order, and were secret combinations to overawe and intimidate.79

1839, Prisoners in jail:

It is inconsistent with the virtue and intelligence of the people of this county longer to maintain a County Prison where the innocent and the guilty are immured together… where the young offender is placed under the tuition and influence of the experienced and hardened criminal; and where secret combinations may be entered into, and plans formed, for the commission of crime.80

1840, Railroad interests:

Irresponsible and secret combinations among railroads always have existed, and so long as the railroad system continues as it now is they unquestionably always will exist. No law can make two corporations, any more than two individuals actively undersell each other in any market if they do not wish to do so. But they can only cease to do so by agreeing in public or private on a price below which neither will sell. If they can not do this public they assuredly do it secretly.81 [Page 98]

1841, Enemies of a bank:

A juncture of affairs, brought about by human agency, originating in folly, or in crime, might be imagined, which would compel banks, in justice to the immediate community around them, to consult the laws of self-preservation, by suspending specie payments for a time, such as secret combinations of foreign and hostile institutions against one bank.82

1845, Opponents of the Medici

The Medici had succeeded up to this period in suppressing all open opposition. They afterwards aspired to supreme authority, and their empire could not be firmly consolidated, till they had put down all secret combinations against them.83

1845, Execution of members of a ruffian band by a vigilante in Texas, as reported in Vermont newspaper:

Hinch and his band had been thoroughly cowed and awed; but the moment this idea occurred to him, the reaction of their base fears was savage exultation. Here was something tangible; their open and united force could easily exterminate an enemy who had acknowledged their weakness in resorting to secret combinations and assassination from ‘the bush!’84 [Page 99]

1846, A temperance society, the Masons, the Odd Fellows, those who sought to murder St. Paul, Judas’s betrayal of Jesus, heathen groups:

“The order of the Sons of Temperance” … makes higher pretences [sic]to charity, &c., than even Masonry and Odd Fellowship; and possesses, equally with them, the very objectionable feature of a band of secret societies extended throughout the country. … Now, how obvious the danger resulting from a secret society, so numerous, and so systematically organized. Every one will acknowledge, that such secret societies are exceedingly dangerous. …

But the principles of your Order are not merely negative. I shall proceed to show, that there are many, and positive evils inseparable from it! We search the Bible in vain for any thing like secret combinations, unless you take such precedents as the band of “more than forty men who bound themselves with an oath,”… or the dark combination between the chief priests and Judas, with the sign, and the pass-word agreed on between them. … No, the principles of the Bible and your Order are at utter war: — but if we go back to the days of idolatry and guilt, in heathen lands, we find many precedents.85

[Page 100]

1846, Greek and other Christians in Palestine:

Unfavorable news was communicated, also, from the Levant. Secret and extended combinations are manifestly forming in high places, against the evangelical Christians of that region. A Greek bishop had called a special meeting of American ecclesiastics and rulers to devise means of getting rid of the missionaries.86

1847, A temperance society; Egyptian, Greek, and Roman groups; Jacobins, Vehmic Court, Carbonari, St. Tammany, Washington Benevolent Society, Free Masons, Odd Fellows:

Secret societies governed by secret laws have always been dangerous and liable to Abuse … the “Order of the S. of T.” bearing in all other respects such a strong family resemblance, we hope the public will be slow to believe that your “secrets” are safer or purer than theirs. These secret moral religious societies, as they were called, were common amongst the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. …

When we come down to the secret societies of modern days, what do we find but a history of intrigue, superstition, blasphemy and wickedness; — not one secret society that ever proved a blessing to mankind. The Jacobin clubs of France … The Vehmic Court, or Secret Tribunal of Westphalia. … The Carbonari, a secret political society in Italy. … The secret order of St. Tammany. … The Washington Benevolent Society … soon, however, found their efforts would be useless in seeking the honours and emoluments of office, because Free Masonry had the precedency [sic] in power and place. … Odd-Fellowship. … From the history of ancient as well as modern secret societies, then, we are admonished to beware of [Page 101]them; … If such secret combinations brought ruin on ancient states, is our Republic in no danger? … Your country bleeding already under the infliction of a dangerous wound from Masonry, into that wound you would drive a Nail … to render it mortal.87

1848, Workmen uniting against employers:

I observe that it is not unusual in the United States for workmen to specify their grievances in writing, and to cause them to be published. … And the practice of giving publicity to these complaints is particularly worthy of commendation. … Instead of those secret combinations, which were formerly so common, and with regard to the merit of which no impartial person could form any judgment whatever; workmen who set themselves up in opposition to the exactions of their employers, feel themselves under an obligation to sustain their conduct by a fair and intelligent exposition of their case.88

1849, Actions of northern abolitionists:

This is one of the charges preferred against us: “Secret combinations are believed to exist in many of the Northern States, whose object is to entice, decoy, entrap, inveigle, and seduce slaves to escape from their owners.”… That Individuals may have acted for themselves in helping the wanderers, and in assisting them … we have no doubt; but of the existence of [Page 102]such secret combinations there is not a shadow of proof. Such combinations are not only unknown to the “States within whose limits they exist,” but also the Abolitionists themselves, who are not so choicely cherished in the North.89

1850, Secret student clubs at the University of Michigan:

If these combined rules are enforced it is morally improbable that any secret combinations can long exist without detection.90

Appendix II — Selected Evidence from Great Britain (1743–1850)

There are many more examples than these, but they provide good sample through time and topic.

1743, English nobles and court intrigue:

Speaking of the events of 1708, one author wrote:

the earl of Wharton excell’d all others in readiness of wit, and quickness of penetration: and he was also very active and indefatigable, by which he got a knowledge of the strength and weakness of those who opposed the publick measures; and seldom fail’d of getting intelligence of their most secret combinations and intrigues. Besides these, there were many of the nobility and gentlemen of the best account who held with the ministry, in all their publick measures; and most of those who distinguish’d themselves by their wit or learning, who naturally approv’d their conduct, as it [Page 103]was the most rational, and the most adapted to the honour and safety of the nation.”91

1757, court intrigue against Frederick III

The tacit Acknowledgment of Count Kaunitz: The Pains taken by the Ruffian Ministers to find a Pretence [sic] for accusing the King of endeavouring [sic] to stir up a Rebellion in the Ukraine: I say, from the Combination of all these Circumstances, there results a Kind of Demonstration of a secret Combination entered into against the King: And it is submitted to the Judgment of the impartial World, whether his Majesty, who had been long informed of all these Particulars, could intirely [sic] discredit positive Advices, which came to him from good Hands, of such a Combination; and, consequently, whether he was not in the Right to demand of the Court of Vienna friendly Explanations and Assurances concerning the Intention of the Armaments.92

1783, a family discord and trial for treason

His younger brothers and sisters were under the unhappy constraint of suing for their fortunes. Then please inform their lordships whether, in truth, there was not a combination in the family against him? I do not mean a criminal one. — I am very certain that was not what my lord alluded to. If you are certain of that, you can inform their lordships what it was that he alluded to? — I will give a reason why I am certain it was not that; because it appeared to be some secret combination: that was a thing publicly known. [Page 104]How did you collect that the combination was secret? — By my lord’s manner of expressing himself. Can you recollect the phrase or the words he used? — I cannot. 93

1802, a faction in the pre-Revolutionary French court

As to count de Broglio, the empress must have been completely deceived by that skilful [sic] politician. He was at the head of the famous secret combination, which never ceased its exertions against the interests of Maria Theresa, in privately thwarting the Austrian alliance of 1756. [The author goes on to underline] “The profound secrecy ever observed by agents of the secret combination.”94

1813, in a translation of Aristotle

Governments change gradually through the secret combination of obscure individuals. At Heraea, the aristocratical mode of appointment to office was changed for one more popular, because a combination of mean mechanics determined to vote for none but persons of their own level. The higher ranks of men, therefore, preferred the capricious decision by lot, to the certain partiality of election. [Marginal note reads: “The secret combination of obscure factions.”]95 [Page 105]

1813, malcontented nobles during the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth now began to be weary of keeping such a prisoner as the queen of Scots. During the former year, the tranquillity [sic] of her government had been disturbed, first by a secret combination of some of her nobles, then by the rebellion of others; and she often declared, not without reason, that Mary was the hidden cause of both. … The detaining her any longer in England, she foresaw, would be made the pretext or occasion of perpetual cabals and insurrections among [her own subjects].96

1823, Irish nationalist groups:

Fellow-countrymen we tell you nothing but the truth. — No goad, no advantage, no benefit, has ever been produced in Ireland by Whiteboyism or Ribbonism, or any other species of secret association. … By the law of the land, any man who joins a secret association, bound together by an oath, or any engagement or promise whatsoever, is liable to be transported. … We have given you this brief abstract of the legal punishments that await the disturbances produced by secret societies. … There is another and a more important object. These secret societies, and the outrages which they generate, are forbidden by the awful voice of religion … We need not tell you how your religion abhors everything that approaches to robbery, murder or blood. … Fellow-countrymen, attend to our advice — we advise you to abstain from all such secret combinations; if you engage in them you not only meet our decided disapprobation, in conjunction with that of your reverend Clergy, but you gratify and delight the basest and bloodiest faction that ever polluted a country — the Orange faction. The Orangemen anxiously [Page 106]desire that you should form Whiteboy, and Ribbon, and other secret societies. …97 Why did he select Orange societies [in Ireland] as the object of his attack? There were other societies bound together by secret oaths as well as the Orange. If the system was objectionable, why not attack those which were obnoxious in principle? But the object was too palpable to deceive the most inexperienced person in parliamentary tactics; and though he acquiesced with the hon. gentleman in his reprobation of all secret combination, yet a distinction ought to be made tween the associations of the loyal and the associations of the disaffected.98

1823, religious dissenters during reigns of Henry VI and Edward IV:

Persecution has ever been powerless against sincerity. … [It] never overcomes true piety or conscientious resolution. … But abstracted from these considerations, and from the ultimate results, persecution tends to occasion immediate evils to all who use it. … It drives the opposed from the public exhibition of themselves and of their actions into secret societies, secret combinations, secret meetings, and secret conversations. … Persecution thus produces confederacies, and makes disloyalty creditable, till the criminality of treason becomes determined by its success. … What government could be safe, or what country happy, in such a state of things! [Page 107]The reigns of Henry VI and Edward IV afford a melancholy illustration of all the ill effects of both religious and political persecutions. 99

1823, American Indians

The Indian broods over his wrongs in secresy [sic], but never forgets them till he has been amply revenged in the blood of his enemy. The first complaints are individual and feeble: when they grow clamorous, a council is convened, the subject is debated, the measure of redress determined, and instantly carried into execution: but sometimes secret combinations of young warriors, anxious to acquire celebrity and distinction, anticipate this form, and the first intelligence which the chiefs have of their scheme is their return from the expedition with scalps and prisoners. 100

1824, Thomas Carlyle’s translation of Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister:

Lydia had put some whims into Theresa’s head concerning Jarno and the Abbé. There are certain plans and secret combinations, with the general scheme of which I am acquainted, and into which I never thought of penetrating farther. … Lothario is begirt with secret influences and combinations.101 [Page 108]

1824, Indian army mutineers during the British Raj:

Mr. Adam thinks that a Free Press would have given the mutinous army certain means of extensive combination, which they could not otherwise enjoy. It is something new to hear of secret combinations (for secret they must have been, to have been of any danger) promoted by a Public Press.102

1830, Washington Irving’s account of a Carib Indian chief:

The most formidable enemy remained to be disposed of, which was Caonabo; to make war upon this fierce and subtle [Carib] chieftain in the depths of his wild woodland territory, and among the fastnesses of his mountains, would have been a work of time, peril, and uncertain issue. In the meanwhile, the [Spanish] settlements would never be safe from his secret combinations and daring enterprises, nor could the mines be worked with security, as they lay in his neighbourhood.103

1832, one hundred 15th-century French factions, all at cross-purposes:

In Louis XIth’s time … [a] hundred secret combinations existed in the different provinces of France and Flanders; numerous private emissaries of the restless Louis, Bohemians, pilgrims, beggars, or agents disguised as such, were everywhere spreading the discontent which it was his policy to maintain in the dominions of Burgundy.104

1850, Methodist faction:

[Page 109]There were individuals who knew what course the special district meeting would adopt, before that meeting had assembled; a secret party, who had prepared things before hand, and who were so confident of carrying through their illegal and unconstitutional measures, that they began to act upon them before the district meeting could assemble. Much is said in the “accredited document,” about “combinations,” “avowed combinations;” but it is these secret combinations, which are not avowed, but are so powerfully felt, that they inflict the deepest wounds on the Methodist constitution, and prove so destructive of the liberties of the church!105

Go here to see the 22 thoughts on ““Cracking the Book of Mormon’s “Secret Combinations”?”” or to comment on it.