Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the tenth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that an independent translation of Isaiah could be so similar to the King James text, while at the same time different from it in such apparently fraudulent ways.

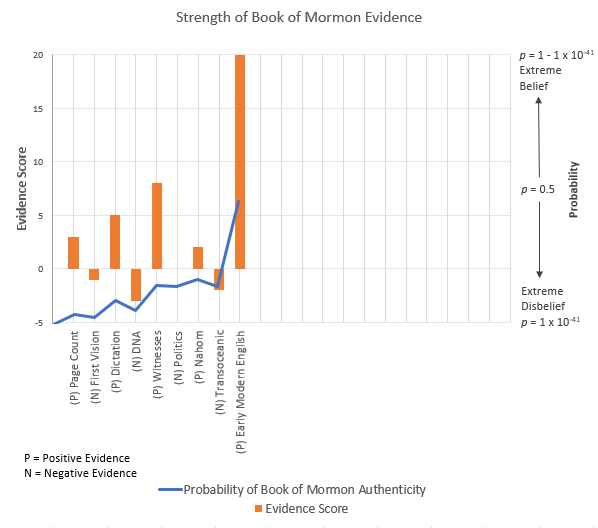

Much has been made of the material shared between the Book of Mormon and the King James Bible, in the Isaiah chapters and elsewhere, with the implication that the material was plagiarized by Joseph as he was writing the Book of Mormon. Yet other critics maintain that the pattern of differences displayed between the Book of Mormon and the King James indicates that Joseph carelessly and ignorantly paraphrased the King James text, rather than translating an authentic text. My analysis here focuses on the differences we see in the Isaiah chapters, comparing the pattern of changes we see with other versions of the Bible. Though the pattern of changes we see in biblical paraphrase aligns closely with the Book of Mormon (p = .46), that pattern would also not have been unexpected from an authentic Book of Mormon given its storied manuscript and translation history. I nonetheless assign a generously low estimate of p = .0001 of observing this evidence if the book is what it claims to be, making this the strongest evidence against the Restoration that we’ve considered thus far.

Evidence Score = -4 (decreasing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by four orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent skeptic, you were trying very hard to push aside what could only be described as a transformational spiritual experience. Your “vision,” surely the product of some bad New England clams, was a distraction—nothing more. What mattered was this book, and in showing clearly its fraudulent nature. And you knew something that just might do the trick. You turn the page to the next chapter, pleased to find exactly what you were looking for. The Nephi described in the text seemed to have a certain affinity for Isaiah, and had a habit of quoting whole chapters from that prophet’s book. But this wasn’t just any Isaiah. You had a hunch that it was the very same Isaiah—word for word—that could be found in the copy of the King James Bible that sat beside you on the table.

There was only one way to know for sure, but your hand hesitates as you begin to move it toward the still-dusty tome. The book lay open to the book of John, to the passage that had driven a stake in what remained of your aging faith only a few days earlier. You had vowed never to touch the book again, but such a vow begged to be broken. After all, this would be in service of an undoubtedly righteous cause.

You carefully, almost reverently, swipe the dust off the fragile pages, turning them back toward the Old Testament. It takes you a moment to find the passage that matches what you were just reading in the other book, but at last you find it, in Isaiah 49:

And now, saith the Lord that formed me from the womb to be his servant, to bring Jacob again to him, Though Israel be not gathered, yet shall I be glorious in the eyes of the Lord, and my God shall be my strength.

The same passage in the other book was almost identical, as quoted by Nephi:

And now, saith the Lord—that formed me from the womb that I should be his servant, to bring Jacob again to him—though Israel be not gathered, yet shall I be glorious in the eyes of the Lord, and my God shall be my strength.

There were slight differences, but the degree of similarity was staggering. As you recall from earlier in the book, Nephi’s passage was supposed to be from a separate text, one that was being quoted by Nephi and then translated through the power of God. Knowing what you do about the process of translation, you find it uncanny that such a process could produce essentially the same word choice. These passages were clearly drawn from the King James, and not only that, but to this specific version of the King James.

Yet the differences between the two texts also seem interesting. You notice that the differences seem tied to the words that had been marked in italics in the King James. It was well known that such italics indicated liberties taken by the King James translators to help smooth the Bible’s English text. Had Smith merely redacted and revised the text as signaled by those italicized words? That would be an odd feature to have in a purportedly inspired translation. It seems unlikely that an independent translation of Isaiah could be so similar to the King James text, while at the same time different from it in such apparently fraudulent ways.

The Introduction

The charge of plagiarism is a common one when it comes to the origin of the Book of Mormon, and nowhere can that charge be so clearly brought to bear than in the case of the Isaiah chapters in 1st and 2nd Nephi. At first the charge might seem to be unfair, and in many cases it is. It is obvious that quotation is not the same as plagiarism, and the mere fact that Nephi is quoting Isaiah doesn’t mean that Joseph is plagiarizing the King James. Still, the nature of that quotation can at times seem strange. The wording of the Isaiah chapters often aligns very closely with the wording of the King James, much more closely than you would expect from independent translations. And the differences that do appear in those texts seem ignorant of the features of the underlying Hebrew text, and also seem to focus on the italicized words of the King James.

Many who look at those cases quickly conclude that Joseph had to have copied those passages directly from his own copy of the Bible. There are, however, some kinks in this theory. For one, Joseph doesn’t seem to have owned a Bible until after he had completed the translation of the Book of Mormon. Second, it appears difficult to definitively identify the version of the King James that Joseph would’ve had to use to make those changes. And third, many of the variations between the Book of Mormon and the King James often show intriguing and surprising parallels to earlier manuscripts, and sometimes show apparently ancient features. Given both sides of the argument, it’s hard to tell which theory the evidence supports and how strongly it does so. Hopefully Bayes can help us get a handle on these conflicting issues.

As we do so, I’ll be focusing specifically on the changes we see in the Isaiah chapters, as these represent the bulk of King James quotations, and also seem to have received the most attention from faithful and critical scholars. It would definitely be possible to expand this analysis to, say, Christ’s quotations from the New Testament in 3rd Nephi, but we’ll save that for another time.

The Analysis

The Evidence

The Book of Mormon quotes a total of 478 verses of Isaiah in the King James Bible. Of these, 201 are worded identically to the King James, and 277 are different in some way. Close examination of similarities note that even the italicized words of the biblical text—words they inserted for ease of reading—are sometimes exactly copied, and sometimes edited in strange ways. Both of these features seem unlikely if those chapters were independent translations from the brass plates, as suggested in the Book of Mormon.

In particular, we need to consider the extensive work of non-LDS biblical scholar David P. Wright on the textual variants in the Isaiah chapters of the Book of Mormon and their corresponding chapters in the King James. His thoroughly documented paper on the subject is available online, and notes a number of features that he finds both surprising and unlikely given the claim that the text is supposed to be a translation of an Isaiah manuscript written in pre-biblical Hebrew. I outline these features below:

Changes related to italicized King James words—Wright notes that a disproportionate amount of the variation in the Isaiah chapters occurs with or around the King James’ italicized words—by his own count, between 22% and 38% of the changes implicate or are near italicized words, despite these words forming only 4% of the King James text of these chapters. This general fact is not disputed by faithful scholars, though they generally argue in return that this means that at least 62% of these changes cannot be explained by proximity to italics. (NOTE: The way Wright compares 4% with 38% is already misleading, since he’s comparing single words to revisions occurring close to those single words—it would be like saying that it would be odd for 38% of the Bible to be within 5 words of the word “the,” even though “The” accounts for only 4% of the text.)

Instances where the Book of Mormon retains King James translation errors—Wright notes a total of 38 cases where the Book of Mormon maintains an apparently problematic King James reading, and where modern translations have opted to render it differently. Note, though, as suggested by Tvedtnes, some of these cases would not have been problematic in the English of the 1820s (or, indeed, in the Early Modern English that pervades much of the Book of Mormon text).

Changes that would have been awkward or unlikely based on the underlying Hebrew—There are 15 cases noted by Wright where he argues that the proposed variation would have been unlikely if the text is based on or evolved from an underlying Hebrew text. One example is 2 Nephi 15:4, where it treats the “wherefore” in the King James as if it meant “therefore,” whereas in the Hebrew the word is “why.” There are also cases where the variations seem to hinder or interrupt an existing Hebrew poetic structure, suggesting that the variation wasn’t part of an original text.

Changes that seem like secondary expansions rather than the primary text—Wright details a number of variations that seem like someone was expanding, explaining, or extrapolating portions of a text, rather than restoring portions of the text that were missing or taken out. This seems odd if the Book of Mormon was merely translating the original Hebrew text, but would be much less mysterious if Joseph was instead making his own revision.

There’s also the issue of Nephi quoting from Deutero-Isaiah, which would be an apparent anachronism. As I see the evidence on that front to be far from definitive, I won’t be treating it here.

Together, these instances make it look an awful lot like someone paraphrasing the King James text of the Isaiah chapters and passing it off as an independent translation. However, faithful scholars have placed a fair amount of attention on these variations as well and add a few additional wrinkles that we’ll need to keep in mind. These include:

Some italics changes go against Joseph’s own likely linguistic preferences—In some cases, italics changes move away from the King James, but not in ways that Joseph would likely have chosen for himself. The key examples are places where the Bible’s personal that syntax is modified in the Book of Mormon to a personal which, such as 2 Nephi 7:11. You’ll recall from the previous episode that the latter sort of syntax is characteristic of Early Modern English and occurs much more rarely in the English of the nineteenth century. Joseph would have been much more comfortable using the personal that already present in the King James—in fact, when revising the Book of Mormon in 1837, many similar instances of personal which were changed to that or whom, though many cases of which still remain.

Scribal errors indicate that the text of the Isaiah chapters was dictated rather than copied—The portions of the original manuscript that are available for the King James quotations reveal scribal errors by Oliver Cowdery, and these indicate errors where words were misheard (e.g., spelling the Lord of Hosts as “the lord of Hoasts”) rather than misread. This corroborates eye-witness testimony that the book’s dictation took place without the aid of a Bible or other notes, which in this case would involve reproducing long verbatim stretches of the King James Bible, as well as the coherent insertion of numerous revisions, and that these were either memorized or came off the top of Joseph’s head. See my previous episode on the unexpected nature of the book’s dictation.

Repeated quotations suggest editorial revisions from the base Isaiah text—There is one particular case where Isaiah 49:25 is quoted twice—once by Nephi in 1 Nephi 21:25, and once by Jacob in 2 Nephi 6:17. Yet these two quotes differ from each other substantially, suggesting that if these are direct quotes from the Brass plates, one of them is wrong. Though this evidence would be consistent with the idea that Joseph is engaging in (inconsistent) paraphrase, it also suggests an intriguing possibility—that those quoting biblical passages are engaging in an editorial expansion of the Isaiah chapters to suit their own rhetorical purposes (i.e., in this case, more clearly outlining God’s promises to his covenant people). Though this type of editorializing makes very good sense in the context of Jacob’s sermon, there’s little reason why Nephi or others couldn’t have done the same as well.

Limited support for the Isaiah variations from earlier Hebrew manuscripts—A goodly number (about 59) of the variations find some support in earlier Hebrew manuscripts, such as the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Masoretic text. An accounting of those differences by Tvedtnes finds that only 21% of the differences seem to directly contradict what could be found in the available manuscripts. Wright holds a rather dim view of these suggestions, though many of his concerns essentially amount to “this is conjectural,” as if it would have been possible for Tvedtnes to do anything other than conjecture given the absence of the gold and brass plates.

Far be it from me to arbitrate disagreements between two scholars as credentialed as Wright and Tvedtnes, let alone the many other commentators who’ve weighed in who are far more qualified than myself. But I’ve tasked myself with thinking these issues through, and I’m going to do so the best way I know how—by consulting the raw data. So how problematic is this evidence, for either side? That depends on what theories you happen to be working with.

The Hypotheses

Joseph was not responsible for the similarities and variations we see between the Book of Mormon and the King James—This theory holds to the evidence provided by the first-hand witnesses of the dictation of the book, who stated unequivocally that Joseph dictated the text without access to notes or to any other text. Not having a text to copy from would mean that similarities to the text of the King James were extant in the words that appeared in the seer stone to Joseph and were not the product of Joseph’s own mind. This theory suggests that if someone is relying on and/or modifying the Isaiah text, they’re doing it prior to it being delivered to Joseph through the seer stone, either through the inspiration or action of the ancient authors or by an unknown translator (or set of translators).

Beyond the statements of those who witnessed the dictation process, the process of dictation and translation underlying the Book of Mormon is a black box. We have little if any idea how the writing on the plates got turned into the words that Joseph saw on the seer stone. Evidence suggests, though, that it was a complex process, and one that defies any kind of simplistic interpretation. It seems unwise to limit ourselves to our intuition or to any pre-existing ideas when we’re trying to sort out how damaging this evidence is for the book’s authenticity.

Being open-minded about the translation and dictation process is helpful, because King James quotations are more damaging for some versions of our theory than for others. That evidence certainly doesn’t align well with the idea that the text of the Book of Mormon is some sort of idealized, unfiltered version of the words of Isaiah as recorded on the Brass Plates—that God made use of a divine universal translator that gave Joseph exactly what Isaiah had in his head when they wrote the text down. But that’s far from the only option at our disposal and isn’t necessarily the option that the Book of Mormon suggests for itself. Here are a few options that could account for that evidence, as I see it:

- Biblical quotations in the Book of Mormon are not direct quotations from the Brass Plates. As suggested above, it’s possible that Nephi and others were actively shaping the text as they went along, either via inspiration or to provide better emphasis for the key doctrines they sought to explore. This would actually help answer a question that I’ve had for a long time—why would Nephi simply reproduce a large portion of words that were already available on the Brass Plates? The inclusion of those chapters makes much more sense if they represent Nephi’s own inspired commentary rather than the words of a text that was already accessible in the brass plates (and would eventually become widely accessible in the modern day). This would explain the secondary nature of many of the Isaiah variations (as Nephi’s changes would have indeed represented secondary expansions to the text) and could explain why many of the changes seem ignorant of the underlying Hebrew (since Nephi is himself modifying that underlying Hebrew before it even gets to its English translators).

- The book received a more traditional translation prior to the words being transmitted to Joseph via the seer stone, and the translator used the King James as a base text when translating biblical quotations, making alterations when necessary. This method is not uncommon, such as in the production of the New King James Version of the Bible. When doing so, they may have attempted to preserve King James language even in some cases where modern translators have chosen to translate things differently. This option accounts for similarities to the King James text within material quoted from the brass plates, as well as cases where King James translation errors have been retained in the Book of Mormon text.

- Whoever was working with the base text of the King James felt, despite a goal to retain King James language more generally, that they had more leeway to alter the italicized words of the King James text, dropping them or replacing them as they saw fit. This would explain why there is such a high volume of changes associated with italics.

- Given the many iterations involved with producing the text of the Book of Mormon (i.e., from Nephi, to Moroni, to its translators, to Joseph, to the original manuscript, to the printer’s manuscript, to the 1830 edition), there would have been numerous opportunities for the text to differ from the King James in ways that are difficult to explain. This would require reemphasizing that Joseph’s claim that the book is “the most correct of any book on Earth” refers to the correctness of the doctrine rather than to the lack of scribal or transmission errors in the texts’ production, as such errors are not only common, they’re integral to understanding the text of the book itself.

With these options in play, the variations identified by Wright are much more easily understood from a faithful perspective. Could they have produced the 38 cases where King James language was preserved despite different modern translation preferences? Could they have produced 15 cases (less than 2% of the 885 variants Wright identifies) where Wright sees issues with the Hebrew of the Masoretic? I don’t see how either of those possibilities is unreasonable or even unlikely given that context.

The similarities and variations between the Book of Mormon and the King James are attributable to Joseph—This theory posits that Joseph did have a Bible in front of him (or had it memorized well enough to extemporize it) while producing the Book of Mormon, and that the passages were copied directly from the Bible while dictating it to his scribes. This would mean that the differences between the King James text and the Book of Mormon were produced by Joseph making changes to the text based on his own preferences (or, potentially, his lapses in memory), including the alteration of the italicized words, which he may have seen as less authoritative. Faithful scholars have argued that Joseph might not have known about what italics would have signified, but I think it’s reasonable to assume that he did know, and that italics would’ve been an easy target for a would-be charlatan trying to pass off the book as an alternative translation.

An assumption common to both theories is that, as is consistent with available evidence, Joseph and his scribes did not know Hebrew at the time that the Book of Mormon was dictated, and that he did not have access to Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible, whether the traditional Masoretic text or any other potential Hebrew primary source.

Prior Probabilities

We’ll refer to our previous episode for our prior probabilities based on the evidence considered thus far.

PH—Prior Probability of Non-Joseph-Authored Variations—Our current estimate for the probability of Joseph producing the book as he and witnesses claimed is starting to get much closer to the realm of the believable, at p = 7.96 x 10-5. You can see how we’ve got to that point in the figure below.

PA—Prior Probability of Joseph-Authored Variations—That would leave the remainder for the prior probability for our naturalistic explanation, or p = 1 – 7.96 x 10-5.

Consequent Probabilities

CA—Consequent Probability of Joseph-Authored Variations—Let’s start with the alternate hypothesis on this one. To get a sense of how likely we would be to observe the evidence we have if Joseph is responsible for those changes, we can look at the evidence that seems to be inconsistent with that hypothesis, particularly the analysis done by John Tvedtnes. When looking at the differences between the King James text and the Book of Mormon in the Isaiah chapters, and then comparing those differences to the original Hebrew Masoretic text, there are times when the Book of Mormon actually appears to provide a superior translation of the original Hebrew than the King James does (let’s call these “hits”). There were other cases where both the King James and the Book of Mormon appear to be valid translations based on the Masoretic text changes (we’ll label these “neutral cases”), and still others that appear to contradict the Hebrew (what we might consider “misses”).

Tvedtnes himself classifies these differences in a similar way and comes up with an interesting pattern: 59 hits, 49 misses, and 126 neutral cases. But he gets these results not only by looking at the Hebrew Masoretic, but at a number of additional manuscripts—it’d be hard to get an exact count of how many he went through trying to look for those hits. Doing so is valid and often fascinating, but it does substantially increase the risk of running into hits purely by chance. And since I don’t know Hebrew and I don’t have nearly as much time at my disposal, I couldn’t really try to replicate what Tvedtnes did. The most I could do was focus on his comparison with the Masoretic. When you do that, you get a different pattern of hits: 4 hits, 43 misses, and 18 neutral cases.

This pattern of hits, misses, and neutral cases is still useful, because we can do our best to replicate what Joseph might have done (i.e., make essentially random changes to the text of the King James) and see if we get the same pattern. Would we expect to get that number of hits? Would we get any at all? It’s hard to know without taking a look.

But making a bunch of random changes ourselves might be a biased way of going about it (as well as extremely tedious) and since (once again!) I don’t know Hebrew, there’s no easy way for me to know if those changes would match the original Masoretic. So, we’ll have to find another way to go about it.

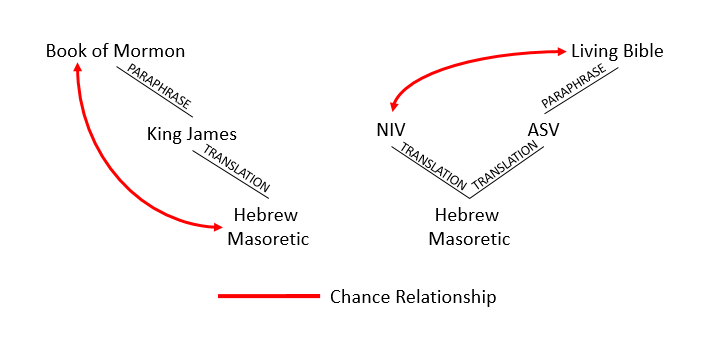

Are there other instances of people making the sort of changes to the biblical text that Joseph is purported to have made? Well, we do have several versions of the Bible that are essentially paraphrases of some other version, which could be close enough for what we need. One example is the Living Bible, a version written by Kenneth Taylor in 1971. This version is a loose paraphrase of the American Standard Version (ASV), which puts it into a more modern vernacular. Conceptually the process of producing this version isn’t altogether different than what we might expect Joseph’s treatment of the Isaiah chapters would’ve been—starting with a base text, words are added, deleted, or changed to suit the preferences of the author. With the Living Bible, those alterations are far more dense than they would’ve been for Joseph and the Book of Mormon, but the types of changes themselves should be comparable.

But to what would we compare it, if not to the original Hebrew? Well, based on the theory we’ve described here, any hits with the Masoretic in the Book of Mormon were due to chance, and they would’ve had just as much chance to match literally any other version of the Bible. So, it doesn’t matter what version of the Bible we choose, as long as we pick one. In this case, I picked the New International Version (NIV).

If changes made by the Living Bible to the ASV happen to line up with the NIV, we could assume that those changes are likely due to chance, in the same way hits with the original Hebrew by the Book of Mormon would be due to chance. We would thus expect the patterns of hits, misses, and neutral cases for our Living Bible comparison to match that same pattern we observe for the Isaiah chapters. The connections between the different manuscripts could be visualized like this:

So what sort of pattern do we see? To find out, I used this site to do a side-by-side comparison of Genesis 1 in the Living Bible, the ASV, and the NIV. I noted every change between the Living Bible and the ASV, in terms of added, deleted, or changed words (see the Appendix for the full list). (I could’ve picked an Isaiah chapter here, but why not start at the beginning?) I then compared that change with the NIV, to see if the NIV agreed with the ASV, with the Living Bible, or if both were equally valid translations. In all, I found 126 differences between the Living Bible and the ASV just in the first chapter of Genesis. As you can see in the table below, some of those changes were actually hits, “supported” by the NIV. A few more were neutral cases. And the vast majority (74%) were misses.

| Type | BofM—Masoretic | Living Bible—NIV |

|---|---|---|

| Hits | 4 (6%) | 8 (6%) |

| Neutral | 18 (28%) | 25 (20%) |

| Misses | 43 (66%) | 93 (74%) |

This is a pattern that makes sense for the types of changes the Living Bible is making. When the Living Bible makes a random change to the text, the odds are low that: 1) the ASV also happens to differ meaningfully with the NIV in that same location (since the ASV and NIV are both relatively strict translations of the same base text), and 2) that the changed language would happen to match that chosen by the NIV (since, if there is a change, there are a lot of potential wording options for the NIV might have chosen in each particular instance). The same should be true of the Book of Mormon and the King James, if Joseph is just making random changes based on preference.

And it is, or at least it seems to be. We can use a simple chi-square test to get the probability of observing both of our patterns if they were produced by the same process. The results show that the two patterns line up quite well with χ2(2) = 1.53, the associated probability being p = .46. That’s a pretty high probability, and it’s the value we’re going to use for the consequent in this case.

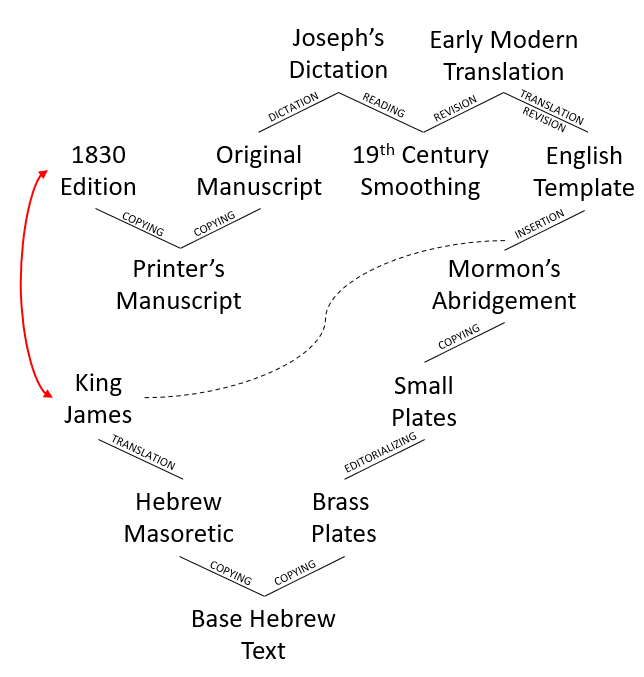

CH—Consequent Probability of Non-Joseph Authored Variations—How likely would we be to observe the kinds of variations we see in the Isaiah chapters if the Book of Mormon is authentic? Well, for starters, it helps to keep in mind the type of complexity we’re working with. You know how we visualized how Joseph would have paraphrased the King James text above? If we tried to visualize how the process would have worked for an authentic Book of Mormon, it could look something like this:

A few things are worth clarifying in this figure. The first is that even before we get the Brass Plates, there’s a copying process that’s currently hidden from us. Both the Masoretic text and the Brass Plates would have been copies of some earlier manuscript of Isaiah which we no longer have and may have even been copies of copies. In the case of the Brass Plates, we have no idea what the quality of that copy is and what might have been changed in the interim. Second, as mentioned above, once we allow for Nephi to editorialize in his versions of the Isaiah chapters, all bets are off. We have no way of telling which of the variations he could’ve been responsible for, and no good to way to distinguish between what might’ve been Nephi’s editorializing and what might’ve been Joseph’s paraphrase. Third, based on the analysis of the text’s Early Modern English, as discussed last time, there appears to be at least two separate processes taking place—an initial translation into Early Modern English (which explains the archaic grammar and syntax) and an editing process to bring the text’s spelling and vocabulary in line with nineteenth-century English (which explains the lack of unfamiliar words and archaic spellings). We have no clue who took part in those translations and revisions, what their motivations and goals were, or what that process looked like. They could be responsible for any number of the variations we see and we’d never be able to tell.

All told, if anyone tells you they understand what the Book of Mormon should have looked like at the end of all that, they’re lying to you. And if we have no idea what the Book of Mormon should look like if it followed those processes, there’s no basis for saying that what we do have is unlikely or unexpected.

But we can still do our best to check, based on what Wright’s given us in his analysis. Given the hypotheses we’ve outlined above, I only see one area that has the potential to be unexpected and that has some hard statistics to back it up, and that’s how the Book of Mormon treats the italicized words of the King James. We might expect a translator working with and modifying the King James text to have felt free to change the italicized words more frequently than other words. But they probably would’ve done so in about the same way that other translations have done it, such as those that are less beholden to the King James. What we might try is comparing how often the italicized words are modified or retained in those other translations with how those are treated in the Book of Mormon.

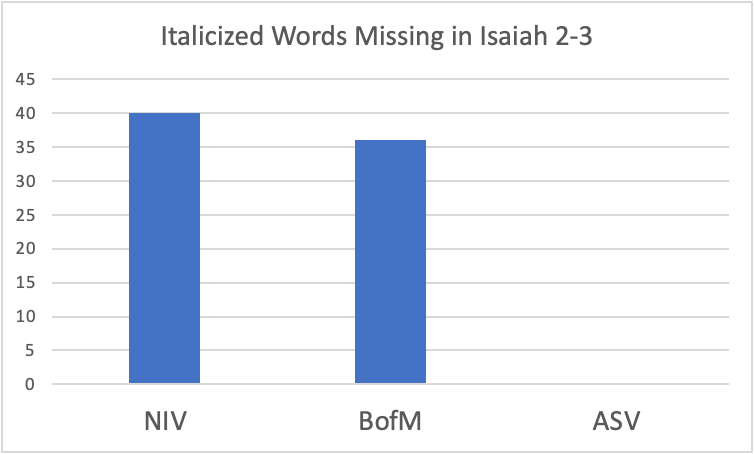

Wright’s done the hard work on that for the Book of Mormon with the lovely table he’s outlined in his paper. He kept track of how many italicized words there were in each of the Isaiah chapters and noted how many of them were kept as-is versus how many had been modified or dropped (40%). What I decided to do was perform those same tallies for two of the same Bible translations that we examined above: the ASV and the NIV. I didn’t have time to do it for all of the Isaiah chapters, but I did it for the first couple chapters of Isaiah that are quoted in the Book of Mormon (Isaiah 2-3).

I included the ASV as a bit of a control condition, since it tries hard to maintain the original King James language where it can, and it turns out that this very much applies to the italicized words. In the chapters I looked at, all of the italicized words were retained—each one was identical to the King James. What was more of a question-mark for me was the NIV. Would such a modern translation bother retaining any of the italicized words, or would it hold on to most of them?

You can see the results in the table below. All told, some of the italicized words were kept around, but most of them were dropped entirely.

| Chapter | Verse | Italicized Word/th> | In NIV | Nearby Variation? | Variation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | that | No | No | |

| 2 | 6 | are | Yes | Yes | and are soothsayers – they are full of superstitions |

| 2 | 7 | is | Yes | Yes | neither is there any – there is no |

| 2 | 7 | there | Yes | No | |

| 2 | 7 | any | No | No | |

| 2 | 7 | is | Yes | Yes | neither is there any – there is no |

| 2 | 7 | there | Yes | No | |

| 2 | 7 | any | No | No | |

| 2 | 12 | shall | No | Yes | of hosts – Almighty; upon every – for all |

| 2 | 12 | be | No | Yes | upon every – for all |

| 2 | 12 | one | No | Yes | high – proud |

| 2 | 12 | that | No | No | |

| 2 | 12 | is | No | No | |

| 2 | 12 | one | No | Yes | upon every – for all |

| 2 | 12 | that | Yes | No | |

| 2 | 12 | is | Yes | Yes | he – they |

| 2 | 13 | that | No | No | |

| 2 | 13 | are | No | No | |

| 2 | 14 | that | No | Yes | upon – (missing) |

| 2 | 14 | are | No | Yes | high – lifted up |

| 2 | 20 | each | No | No | |

| 2 | 20 | one | No | Yes | for himself – (missing) |

| 2 | 22 | is | No | Yes | whose – who have but a |

| 3 | 4 | to | No | Yes | give children – make mere youths |

| 3 | 4 | be | No | No | |

| 3 | 6 | saying | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 6 | let | No | No | |

| 3 | 6 | be | No | Yes | let ruin be under thy hand – take charge of this heap of ruins |

| 3 | 7 | is | No | Yes | food – bread |

| 3 | 8 | are | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 9 | it | Yes | Yes | their soul – them |

| 3 | 10 | it | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 10 | shall | No | Yes | shall – will |

| 3 | 10 | be | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 10 | with | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 10 | him | Yes | Yes | eat – enjoy |

| 3 | 11 | it | No | No | |

| 3 | 11 | shall | No | No | |

| 3 | 11 | be | No | No | |

| 3 | 11 | with | No | Yes | ill – disaster is upon |

| 3 | 11 | him | No | Yes | upon them – with him |

| 3 | 12 | for | No | No | |

| 3 | 12 | are | No | Yes | children are their oppressors – youth oppress |

| 3 | 12 | thee | No | Yes | cause thee to err – lead you astray |

| 3 | 14 | is | Yes | No | |

| 3 | 15 | that | No | Yes | ye beat my people to pieces – by crushing my people |

| 3 | 16 | as | No | Yes | walking and mincing – struggling along with swaying hips |

| 3 | 18 | their | Yes | Yes | the bravery – their finery |

| 3 | 18 | about | No | No | |

| 3 | 18 | their | No | No | |

| 3 | 18 | feet | No | No | |

| 3 | 18 | their | No | No | |

| 3 | 18 | their | No | Yes | round tires like the moon – crescent necklaces |

| 3 | 24 | that | No | Yes | and it shall come to pass – (missing) |

| 3 | 24 | and | No | Yes | burning – branding |

| 3 | 26 | being | No | No |

Comparing these to how the Book of Mormon treats the italicized words, we get the figure below:

Based on this, the Book of Mormon seems to fall within the range of how other translations treat the italicized words. It doesn’t retain them nearly whole-cloth like the ASV, but it doesn’t alter them to the extent that the NIV does either. In these raw frequencies, at least, there’s no statistical basis for saying that the Book of Mormon’s treatment of italics is unexpected.

You’ll also notice in the table above that I kept track of variations between the King James and the NIV that occur adjacent to the italicized words, similar to how Wright identifies variations in the Isaiah chapters that occur near italicized words in the King James (rather than revision to the italicized words themselves). Wright claims that these variations could have been triggered by the nearness of the italicized words, suggesting that they represented a signal for Joseph to start paraphrasing. But there’s clearly plenty of variants between the NIV and the King James that are adjacent to italics too. The nature of the adjacent variants for the NIV is obviously different than for the ones in the Book of Mormon (since the underlying meanings generally stay the same). But if I wanted to argue that italics were “triggering” variants in the NIV, I’d have plenty of ammunition to work with.

That argument would be wrong—the NIV has plenty of variants everywhere, not just near italicized words—but that’s the point. The fact that I could build this false argument for the NIV suggests that Wright’s argument for the Book of Mormon could be similarly illusory.

To get a sense whether it could be, we need to know how the Isaiah variants are distributed if you exclude changes to the italicized words themselves. It would be genuinely weird if Nephi were biasing his editorial commentary toward verses that would have italicized words two thousand years later. But to know whether he did, we need to know if non-italics revisions (which Wright terms “environmental variants”) really were disproportionally grouped around the italics, or if the changes to the italics themselves were just making it seem that way.

The problem is that Wright’s table doesn’t really help us in that quest. He doesn’t report the raw data (just the aggregated frequencies) and doesn’t distinguish between environmental variants and ones made directly to the italicized words. So, I decided to do my own minor count, based on the 97 verses in Isaiah 2-6—not a random sample, but large enough to be useful. I compared the 2013 Book of Mormon to the LDS edition of the King James, noting any changes that didn’t involve italicized words. You can see the full set of noted changes in the appendix, and a summary in the table below.

| Has Italics | No Italics | |

|---|---|---|

| Non-italics Change | 15 (33%) | 15 (28%) |

| No Change | 30 (66%) | 37 (71%) |

Verses with italics were only slightly more likely to see non-italics related changes (33%) than were verses without italics (28%), and this difference wasn’t remotely significant, χ2(1) = 0.22, p = .63. Until someone can demonstrate to me otherwise, I have to assume that Wright’s “environmental variants” argument is 100% illusory. The raw number of Isaiah variants in the Book of Mormon gives him plenty of cherry-picked examples with which he can build his case, but I see no basis to conclude that his “environmental revisions” were any more likely to be triggered by italicized words than by any other word in the text.

So, if we can’t draw any statistical conclusions from Wright’s data, and the nature of the Book of Mormon is too complex to properly orient our analysis, where does that leave our assessment of the evidence? Given what Wright presents, I can’t say that the evidence doesn’t look bad for the Book of Mormon—suggesting that Joseph paraphrased the King James is certainly a simpler explanation than positing such a complicated revision history, even if complicated is exactly what we’d get if the book were authentic. Thus, to help adjust for the Book of Mormon’s more complex assumptions, and to acknowledge Wright’s thorough analysis, we’ll assign a generous consequent probability of p = .0001.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon, or p = 7.96 x 10-5)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (our estimate of the likelihood of observing the differences between the Book of Mormon and the King James that we do, if Joseph wasn’t relying on the Bible to produce them, or p = .0001)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the probability of a fraudulent Book of Mormon, or p = 1 – 7.96 x 10-5)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our estimate of the probability of observing those differences if Joseph was paraphrasing from the King James, or p = .46)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 7.96 x 10-5 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (7.96 x 10-5 * .0001) |

| ((7.96 x 10-5) * .0001) + (1 – 7.96 x 10-5) * .46) | |

| PostProb = | 1.73 x 10-8 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(.0001/.46)

Lmag = log10(.000217)

Lmag = -4

Conclusion

What did we learn, then, from all this? Hopefully that the issues surrounding comparisons with the King James aren’t as cut and dried as we’d be tempted to think. The Book of Mormon doesn’t simply copy and paste the King James text, as some critics imply, and a critical analysis of its variants isn’t as decisive as some might expect. And on the other hand, the evidence from faithful scholars regarding support from early manuscripts, as interesting as it is, could have been produced by chance through a paraphrasing process. The evidence in this area is complex and difficult, providing no obvious silver bullet to either side.

In the end, I’ve chosen to handicap the Book of Mormon for that additional complexity, though doing so by several orders of magnitude is probably too generous. This evidence takes us a few steps back from belief in an authentic Book of Mormon, though we’ll see if that’s enough to hold back the tide in the end.

Skeptic’s Corner

If my analyses leave you feeling a bit unsatisfied, don’t worry—that’s a good feeling for a true skeptic to have. If I were in a critic’s shoes, this would look a whole lot like moving the goalposts back to sit by a strained and obscure theoretical framework, completed using the effervescent power of mental gymnastics. But I have no problem adopting a theory if that theory is a better fit for the evidence, and so-called “mental gymnastics” are the only path to truth in an uncertain and complex world.

In the end, though, there’s a lot here that still needs to be done that I just couldn’t do (e.g., a hard look at the underlying Hebrew), or that I didn’t have time for (e.g., completing my count of non-italics variations using Skousen’s Earliest Text, or his and Carmack’s recent collation of King James variants. It would be entirely possible for future research to unearth something genuinely unexpected within the Isaiah variants (e.g., non-italics variations that are unexpectedly close to italicized words even within specific verses; ties to specific earlier manuscripts other than the Masoretic that exceed what could be produced by chance), but neither Wright’s nor Tvedtnes’ analyses seem to fit the bill. I move on from this evidence having given it more attention than most, yet with little more to show for it than a placeholder weighing tentatively on the side of the critics.

Next Time, in Episode 11:

In the next episode, we’ll be taking a look at computer-based studies of word patterns in the Book of Mormon, assessing the probability of finding those results by chance alone.

Questions, ideas, and voodoo curses can be pinned into the likeness of BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

Table 1. Comparing Biblical Paraphrase in Genesis 1 to Other Translations (Living Bible/ASV/NIV)

| Verse | Variation from ASV | Support in NIV? |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | When | No |

| 1 | Began creating | No |

| 2 | Shapeless | Yes |

| 2 | Chaotic | No |

| 2 | Brooding over | Yes |

| 2 | Dark | No |

| 2 | Vapors | Neutral |

| 3 | Light appeared | No |

| 4 | [Saw] | No |

| 4 | Was pleased with it | No |

| 4 | [God] | No |

| 5 | [He called] | No |

| 5 | Together | No |

| 5 | they formed | No |

| 5 | The first | Yes |

| 6 | Vapors | Neutral |

| 6 | [Firmament] | No |

| 6 | Separate | Neutral |

| 6 | Form | No |

| 6 | Sky above | No |

| 6 | Oceans below | No |

| 7 | So | Yes |

| 7 | Sky | Neutral |

| 8 | [And God called the firmament heaven] | No |

| 8 | This all happened on | No |

| 8 | [There was evening] | No |

| 8 | [There was morning] | No |

| 9 | Then | No |

| 9 | Beneath | Neutral |

| 9 | Sky | Neutral |

| 9 | Into oceans | No |

| 9 | So that | No |

| 9 | Emerge | Neutral |

| 10 | Then | No |

| 10 | Named | Neutral |

| 10 | [Gathering together] | No |

| 10 | [Called he] | No |

| 10 | Was pleased | No |

| 11 | Burst | Neutral |

| 11 | Every sort of | No |

| 11 | Seed-bearing plant | Neutral |

| 12 | Seeds will produce | No |

| 12 | Was pleased | No |

| 13 | This all occurred | No |

| 13 | [There was evening] | No |

| 13 | [There was morning] | No |

| 14 | Bright | No |

| 14 | Appear | Neutral |

| 14 | [In the firmament] | No |

| 14 | Identify | Neutral |

| 14 | They shall bring about | No |

| 14 | [for signs] | No |

| 14 | On the earth | No |

| 14 | Mark | Yes |

| 15 | [Lights in the firmament] | No |

| 16 | For | Neutral |

| 16 | Huge | Neutral |

| 16 | The sun and moon | No |

| 16 | To shine down | No |

| 16 | Upon the earth | No |

| 16 | The sun | No |

| 16 | Preside | Neutral |

| 16 | The moon | No |

| 16 | Preside | Neutral |

| 16 | Through | No |

| 17 | [In the firmament] | No |

| 18 | Preside | Neutral |

| 18 | Was pleased | No |

| 19 | This all happened on | No |

| 19 | [There was evening] | No |

| 19 | [There was morning] | No |

| 20 | Then | No |

| 20 | Teem | Yes |

| 20 | With fish | No |

| 20 | The skies be filled | No |

| 20 | Of every kind | No |

| 21 | Animals | Neutral |

| 21 | Fish | No |

| 21 | [That moveth] | No |

| 21 | With pleasure | No |

| 22 | [Be fruitful] | No |

| 22 | [The water] | No |

| 22 | And to the birds he said | No |

| 22 | Numbers increase | Yes |

| 22 | Fill | No |

| 23 | That ended | No |

| 23 | [There was evening] | No |

| 23 | [There was morning] | No |

| 24 | Of animal | No |

| 24 | Reptiles | No |

| 24 | Wildlife | Neutral |

| 25 | [God] | Yes |

| 25 | Wild animals | Neutral |

| 25 | [After their kind] | No |

| 25 | [Everything that] | No |

| 25 | Pleased with | No |

| 26 | Then | No |

| 26 | Someone like ourselves | No |

| 26 | [In our likeness] | No |

| 26 | To be the master | Neutral |

| 26 | [Over the fish] | No |

| 26 | [Over the birds] | No |

| 26 | [Over the cattle] | No |

| 26 | [Over everything that creepeth] | No |

| 27 | Like his Maker | No |

| 28 | [Be fruitful] | No |

| 28 | You are masters | Neutral |

| 28 | [Of the sea] | No |

| 28 | [Of the heaven] | No |

| 28 | [Over everything that moveth] | No |

| 29 | [God said] | No |

| 29 | Seed bearing plant | Neutral |

| 29 | [Upon the face] | No |

| 29 | [In which is the fruit] | No |

| 30 | The grass | No |

| 30 | [Green] | No |

| 30 | [Of the sea] | No |

| 30 | [Of the heaven] | No |

| 30 | [Over everything that moveth] | No |

| 30 | [And it was so] | No |

| 31 | Then | Neutral |

| 31 | [Behold] | No |

| 31 | In every way | No |

| 31 | Excellent | Neutral |

| 31 | [There was evening] | No |

| 31 | [There was morning] | No |

Table 2. Non-Italics-Related Variants in Isaiah 2-6

| Chapter | Verse | Has Italics | BofM Has Non-Italics Changes | Non-Italics Change Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 2 | Y | ||

| 2 | 3 | |||

| 2 | 4 | |||

| 2 | 5 | Y | addition of an entire phrase “yea, come, for ye have all gone astray…” | |

| 2 | 6 | Y | ||

| 2 | 7 | Y | ||

| 2 | 8 | Y | also is – is also | |

| 2 | 9 | Y | boweth down – boweth not down; humbleth himself – humbleth himself not | |

| 2 | 10 | Y | addition of “oh ye wicked ones” | |

| 2 | 11 | Y | addition of “and it shall come to pass” | |

| 2 | 12 | Y | Y | addition of “all nations, yea upon” |

| 2 | 13 | Y | Y | addition of “yea, and the daily of the Lord shall come” |

| 2 | 14 | Y | Y | addition of “and upon all the nations” and “and upon every people” |

| 2 | 15 | |||

| 2 | 16 | Y | addition of “and upon all the ships of the sea” | |

| 2 | 17 | |||

| 2 | 18 | |||

| 2 | 19 | Y | additions within “for the fear of the Lord shall come upon them” and of “shall smite them” | |

| 2 | 20 | Y | ||

| 2 | 21 | Y | additions within “for the fear of the Lord shall come upon them” and of “shall smite them” | |

| 2 | 22 | |||

| 3 | 1 | Y | stay – staff | |

| 3 | 2 | |||

| 3 | 3 | |||

| 3 | 4 | Y | Y | addition of “unto them” |

| 3 | 5 | |||

| 3 | 6 | Y | Y | addition of “not” |

| 3 | 7 | Y | ||

| 3 | 8 | Y | Y | tongue – tongues |

| 3 | 9 | Y | Y | additon of “to be even” |

| 3 | 10 | Y | ||

| 3 | 11 | Y | Y | it shall be ill with him – for they shall perish |

| 3 | 12 | Y | ||

| 3 | 13 | |||

| 3 | 14 | Y | ||

| 3 | 15 | Y | ||

| 3 | 16 | Y | ||

| 3 | 17 | |||

| 3 | 18 | Y | ||

| 3 | 19 | |||

| 3 | 20 | |||

| 3 | 21 | |||

| 3 | 22 | |||

| 3 | 23 | |||

| 3 | 24 | Y | ||

| 3 | 25 | |||

| 3 | 26 | Y | ||

| 4 | 1 | |||

| 4 | 2 | Y | ||

| 4 | 3 | Y | ||

| 4 | 4 | |||

| 4 | 5 | Y | ||

| 4 | 6 | |||

| 5 | 1 | Y | now – and then | |

| 5 | 2 | |||

| 5 | 3 | |||

| 5 | 4 | Y | brought it – it brought | |

| 5 | 5 | Y | Y | break – I will break |

| 5 | 6 | |||

| 5 | 7 | Y | ||

| 5 | 8 | Y | Y | removal of “that lay field to field” |

| 5 | 9 | Y | Y | great and fair – great and fair cities |

| 5 | 10 | |||

| 5 | 11 | Y | ||

| 5 | 12 | |||

| 5 | 13 | Y | ||

| 5 | 14 | |||

| 5 | 15 | |||

| 5 | 16 | |||

| 5 | 17 | |||

| 5 | 18 | |||

| 5 | 19 | Y | ||

| 5 | 20 | |||

| 5 | 21 | Y | ||

| 5 | 22 | Y | ||

| 5 | 23 | |||

| 5 | 24 | Y | ||

| 5 | 25 | Y | ||

| 5 | 26 | |||

| 5 | 27 | |||

| 5 | 28 | Y | Y | their horses’ hoofs – and their horses’ hoofs |

| 5 | 29 | Y | ||

| 5 | 30 | Y | ||

| 6 | 1 | |||

| 6 | 2 | Y | seraphims – seraphim | |

| 6 | 3 | Y | ||

| 6 | 4 | |||

| 6 | 5 | Y | ||

| 6 | 6 | Y | ||

| 6 | 7 | Y | ||

| 6 | 8 | Y | Y | said I – I said |

| 6 | 9 | Y | understand – understood; perceive – they perceived | |

| 6 | 10 | Y | convert – be converted | |

| 6 | 11 | Y | answered – said | |

| 6 | 12 | Y | Y | and – for |

| 6 | 13 | Y | Y | yet in it – yet there |

One thing I know and one thing that everyone seems to keep forgetting is that the Book of Mormon was first published in 1830. The people who lived then and the people who have lived since then are certainly different from those of us who live today. Just because we have standards that seem universal, we should not forget that there were other standards in bygone days.

For example, if the Book of Mormon had been printed in 1830 with substantial changes in the King James wording beyond what are already found within the book, then at that time and up until almost the current day, –at least until the day when ancient texts previously unknown were forthcoming– any substantial changes would have forced a majority of the populace to cry “foul,” “a work of darkness” and probably even claims of “outright blasphemy.” (It happens enough already without people actually ever having read the book…) It would not have been surprising for many of that day to have spurned the book without ever having given it more notice than they were already wont not to do.

No one familiar with the Bible in that day (and there were lots of people who knew their Bible far better than most of us know it today,) I repeat, no one would have accepted or even bothered to consider a book that went “beyond” their beloved Bible. People between recent day and two hundred years ago would have been angry, disgusted and leery of anyone daring to radically break from their traditional Bible.

From a sales standpoint only: if you want your product to sale (i.e. to be successful,) you cannot alienate every person who encounters it. Radical departure from KJV English wording would have dismayed a huge percentage of those people. The few changes apparent within the text were obviously permissible to them, except as they felt “borrowing” or “plagiarism” had occurred. At least none of them demanded Joseph be burned at the stake or hung from the neck for the heresy of defacing the holy words of the Bible. At least a goodly portion of those who read the book with humility and open-mindedness, were willing to ponder the words within, and were then willing to ask God of its genuineness, received an answer to their questions and their prayers. This is the mark of successful standardizing so that those willing to read could obtain their own testimony and not throw it out because it offended any prior conceived moral sensibilities as to differences between it and the Bible.

It is just very ironic that today (years after its initial publication) that today when other sources have become available which have been used to condemn the book should ignore all the internal proofs provided them. Those who condemn the book for these reasons are rarely willing to consider the internal proofs which at the very least negate their discomfort. For instance, the use of eModE, Chiasmus, Janus parallelism, onomastic wordplay, tricola and tetracola, symmetry with ancient-world daily practices (such as: caravans, nomadic lifestyle, burial place names, and vineyard practices.) If those who condemn the book for those few idiosyncracies which neither they nor we can as yet fully explain between the King James Version and the text, –if they cannot see beyond that one trivial issue (which I am certain a Divine Majesty can and will explain in His own proper time,) –if they cannot see beyond their little issue to all of the other recent discoveries and internal proofs, then their bias is telling indeed.

Beyond all that, let the Book of Mormon stand or fall on the Spiritual manifestation evident from within its own covers and regardless of man’s incomplete understanding of what is within those same covers.

There’s a FARMS analysis somewhere that compares the JS version of Isaiah in the Bible to the latest translation of Isaiah based on the original text. The analysis found that the BoM editions of Isaiah actually *agreed* with the latest (and completely independent of the BoM) modern translations of Isaiah *more* than they agreed with the original JST. In other words, JS just *happened* to produce a BoM with Isaiah changes that are strikingly similar to the latest work to more accurately translate Isaiah into English. I’m sorry I don’t have a link, I read it back when I was at BYU, somewhere around 2014.

That’s definitely be an interesting one to look at, and one that’d probably be actionable from a Bayesian perspective (e.g., estimating the odds that two independent paraphrastic translations could show different correlations with a third). I can’t seem to find it, so if you run into it again I’d appreciate you throwing it my way.

Also, if you’re the guy that replied to me on twitter, thanks for reading. Glad that exchange is getting a few more eyeballs on these.

Yes, I’m the guy from Twitter! I really appreciated finding your work here. Also, it took me ages but I was able to track down the work I mentioned, though in the years since I read it the nuances shifted slightly. What you’ll find here is a Hebrew expert comparing (exhaustively) minute variations in the Isaiah texts in the Book of Mormon to the KJV, and cross-referencing them with the actual Hebrew texts that scholars rely on for these Isaiah passages. His knowledge of Hebrew is deep, and the roots of some of the variations/errors go down to the Hebrew letters and the most common scribal errors that could have arisen in the Hebrew records themselves, and then again in the translations from Hebrew to English. But, TLDR, the volume of variations supports the Book of Mormon variants as being closer to the original Hebrew more often than the KJV: https://rsc.byu.edu/isaiah-prophets/isaiah-variants-book-mormon

Part 2 of 2

Of the chapters in Isaiah that are replicated in the Book of Mormon, Dr. Wright identifies 38 passages in the KJV translation of Isaiah where the translation is “clearly or very likely wrong.” Not just variances in word choice, but actually errors. Latter-day Saints believe the Bible to be the word of God “inasmuch as it is translated correctly,” but place no such qualification on the translation of the Book of Mormon.

Of course, the Book of Mormon itself says that it isn’t perfect. But how many of these errors should we expect to persist? I could say I would expect a book that is believed without the “inasmuch as it is translated correctly” qualification to fix at least 95% of the problems. After all, if this really were independently translated with divine help, what are the chances that not only it would contain mistakes, but would actually replicate the mistakes of an inferior translation?

Out of an abundance of I’m going to assume that a book translated by the power of God for the expressed purpose of giving us a pristine translation of what God really told his ancient prophets would fix 80% of these problems.

It turns out that none of these problems were fixed. Zero. None. Using a binomial distribution with a sample size of 38 and a probability of success equal to 80%, the chance of having zero fixes is p = 2.74878 x 10^-27.

Additionally, Dr. Wright demonstrates that the changes that were made weren’t done in ways that could be considered valid alternative translations of the Hebrew that showed an understanding of Hebrew language, text, style, and context, but rather were reactions to the KJV as interpreted by 19th century Christians. I could count up the incidences of this happening, assign some arbitrary probabilities to each, and then generate any arbitrarily low probability that I wanted, but I don’t really have the time or inclination to do that.

Thanks for your thoughts, Billy.

I’d complain that you’d failed to actually engage with the content of the essay, but at this point that’s pretty much par for the course. Let’s take a look at what you’ve got for us, though.

“It turns out that none of these problems were fixed. Zero.”

This statement is already incorrect, because, as noted in the essay, Tvednes identifies at least four cases where the BofM differs from the KJV, and yet is a better match for the Masoretic. That alone would snip five orders of magnitude off your estimate. It still appears to leave a pretty big hole to dig out of, but it does seem to suggest that you might not be seeing this clearly.

And thankfully the BofM isn’t actually in that hole. Your analysis assumes that God cares about correcting translation errors (none of which particularly substantive in regards to doctrine). I don’t think that he does. You might think at first glance that this is some sort of cop-out, and that I’m just relying on the idea that “God’s ways are not our way”, but I’m not. In this case, God’s ways could very much be our ways, and literally so.

We could start by asking ourselves a slightly different question: Does the modern church care about correcting translation errors? The answer to that is clearly no. We’ve stubbornly stuck with the King James as our standard version of the Bible since the very beginning, and this despite having the JST right at our fingertips. If an accurate representation of the Masoretic was high on the church’s priority list, we’d have had our own translation of the Bible decades ago.

And why don’t we? I’m not sure what’s in the minds of the brethren, but I’d suspect it has to do with 1) maintaining scriptural unity, and 2) respecting tradition. And if the church could think that way, it should be possible that God (or those assisting him) would think that way too.

How likely would it be for the BofM’s translator(s) to maintain a strong preference for the King James text, except in cases of italics or for Nephi’s editorial changes, even if maintained an apparent error? (Not to mention cases where those translators might have even preferred the King James interpretation over a modern one.) I don’t know, but it’s going to be less than 2.7 x 10^27.

“the changes that were made weren’t done in ways that could be considered valid alternative translations of the Hebrew that showed an understanding of Hebrew language, text, style, and context”

And each of these could be explained just as well by Nephi making the change rather than Joseph. There may be a few that Wright interprets as fitting a 19th century context, but there are just as many or more that Tvedtnes interprets as fitting an ancient one. Which means we’re at an impasse. All that needs to be dealt with on the faithful side is the possibility of Nephi making those changes. And I think an evidence score of 4 covers that pretty well.

“I’d complain that you’d failed to actually engage with the content of the essay…”

And your essay didn’t actually engage with the content of Wright’s paper.

From my seat, David P. Wright has authoritatively and definitively proven that the Isaiah chapters in the Book of Mormon aren’t a translation of ancient plates, but rather a reworking of the KJV by an English-speaking Christian. Tvedtnes might speculate that one of Joseph Smith’s variants might be a marginally better translation of the Massoretic and another might be a marginally better translation of the Septuagint, or whatever. But these alleged “hits” are the result of data mining and have no predictive power. Pointing out their existence doesn’t refute Wright’s detailed and comprehensive argument.

That’s what is clear to me, at least. If there is a qualified scholar that disagrees, they are free to make his case to a scholarly audience.

“And to be honest, taking yet another look at Wright’s KJV error examples, most of these are…less than definitive. I don’t see much conceptual difference, for example, between “provok[ing] the eye of the Lord” and “rebel[ing] against his glorious gaze”.”

It’s interesting that you disregard this as “less than definitive”, yet are impressed with Tvedtnes’s arguments. Tvedtnes admittedly cherry picks examples that shed a “favorable light” on the BoM and comes up with examples like the following, “Isaiah 14:3 compared with 2 Nephi 24:3: KJV reads “the day,’’ while BM reads ‘‘that day.’’ Though MT agrees with KJV, there are some Hebrew manuscripts which add h-hw’, “that.”” (see https://rsc.byu.edu/isaiah-prophets/isaiah-variants-book-mormon)

Just as you are free to think EModE is spectacularly strong evidence of the BoM being authentic, you are free to disregard Wright’s superior analysis as much as you need to.

I’ll make an exception, since my initial comments were fragmented and there’s quite a bit here worth responding to.

“And your essay didn’t actually engage with the content of Wright’s paper.”

If you call accurately describing and responding to his arguments “not engaging”, then you can do that, I suppose.

“From my seat, David P. Wright has authoritatively and definitively proven that the Isaiah chapters in the Book of Mormon aren’t a translation of ancient plates, but rather a reworking of the KJV by an English-speaking Christian.”

On the grounds that you’ve described here? If so, you haven’t succeeded in articulating that point. I see other possibilities that you’ve neglected to give any air to, either in your arguments or in your own mind.

“But these alleged “hits” are the result of data mining and have no predictive power.”

It’s Tvedtnes data mining vs. Wright’s data mining, and I think I’ve been able to show quite clearly that Wright’s data mining led him down at least one blind alley (i.e., his environmental variants argument, which I’ll note you’re not promoting here). I see both their arguments as conjectural, and Wright’s list of KJV errors consists of some considerable stretching.

When identifying KJV errors, the issue shouldn’t be identifying places where modern translators make different decisions when rendering the text. It should be identifying places where, when comparing the KJV and Nephi’s record, an Early Modern translator would feel compelled to make a change on conceptual or doctrinal grounds. I don’t think we know enough about the translation to make a firm declaration (which is most of the issue here), but it’s clear that latter list should be much shorter than 38, since Wright includes a great many cases that are either conceptual equivalents, areas where there seems to be limited consensus among translators, and instances where modern translators themselves depart from the MT.

“If there is a qualified scholar that disagrees, they are free to make his case to a scholarly audience.”

Gee Billy, I would never have expected you to make an argument from authority here. I suppose I’ll just have to pay attention to people’s credentials instead of their arguments from now on.

For the record, though, I’d love to see someone with mastery of the relevant languages take another solid crack at the issue.

“Just as you are free to think EModE is spectacularly strong evidence of the BoM being authentic, you are free to disregard Wright’s superior analysis as much as you need to.”

I decided to give the KJV evidence quite a bit of heft against an authentic BofM. You decided that EModE was evidence in your favor. I don’t think it makes sense to conflate our two approaches.

Cheers!

Regarding my alleged appeal to authority, it’s not about somebody’s credentials per se. Rather, it is about having the requisite background knowledge and investing the requisite time to make and recognize quality arguments. In your own words, “there’s a lot here that still needs to be done that I just couldn’t do (e.g., a hard look at the underlying Hebrew), or that I didn’t have time for.” There is no shame in that, but it does seem pointless to get into an extended debate with somebody who hasn’t done their homework, especially in the comment section of this forum.

One person who meets these qualifications has the unique honor of having written the very first article in the history of “Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Thought.” I wonder what David Bokovoy would think about the quality of Tvedtnes’s and Wright’s respective arguments? Perhaps you could reach out to him and see if he can set me straight?

In any event, I haven’t updated my odds based upon this new evidence. This evidence is perfectly correlated with the EModE evidence from last week, which includes how the BoM is extremely concerned with the issues of 16th to 18th century Christianity. Because of this correlation, I can’t validly multiply new odds here with the existing odds. My needle is unmoved and I’m still at 40M-to-1.

And to be honest, taking yet another look at Wright’s KJV error examples, most of these are…less than definitive. I don’t see much conceptual difference, for example, between “provok[ing] the eye of the Lord” and “rebel[ing] against his glorious gaze”. Wright might turn his nose up at them, but for the majority I can see where the KJV translators could’ve been coming from. And if the translators happened to have been situated in a somewhat more archaic mindset (e.g., an Early Modern one), they could’ve totally had a preference for the KJV rendering even if it wasn’t a perfect fit for the underlying vorlage.

And, what’s more, it’s not counting the various cases where the KJV represents the closer rendering of the Hebrew on the page, and it’s modern translators who make the conjectural emendation.

And that’s used up my three responses, so I guess you get the last word!

Part 1 of 2:

I’m going to offer a two-part response here. First, I’m going to do my best to very briefly summarize Dr. David P. Wright’s arguments in layman’s terms, as best as I understand them. In a follow-up post, I will apply a statistical analysis to part of what he says, in a way as consistent as possible with what Kyler has done in previous episodes.

Before I begin, I want to commend Kyler and the Interpreter Foundation for acknowledging these issues and providing links to Dr. Wright’s paper. Dr. Wright is a full professor at one of the top Jewish universities in the country where he teaches the Hebrew Bible at the graduate level. His paper “Isaiah in the Book of Mormon…and Joseph Smith in Isaiah” is a top-notch scholarly examination of this issue. (Here is a repeat of the link, which Kyler referred to above: http://user.xmission.com/~research/central/isabm1.html)

Stated as briefly as possible, Joseph Smith was correct when he said there were various problems with the translation of the Bible. There are variants in how the Hebrew bible has been transcribed over the eons, and it isn’t always clear which variant is closer to the original. Furthermore, there are in fact issues in the translation with the KJV.

The main problems for Isaiah in the Book of Mormon are three-fold:

1- The Book of Mormon contains entire chapters of the Old Testament that could not have been in the brass plates because they were written after Lehi supposedly left Jerusalem.

2- There are multiple known problems in the KJV translation that the Book of Mormon replicates rather than fixes.

3- There are multiple passages that were translated correctly in the KJV, but were rewritten and corrupted in a way that was obviously based on an English Christian reinterpreting the KJV , and not on a translation of any authentic ancient Hebrew manuscript, either known or unknown.

For these reasons, we can be confident that the Isaiah chapters do not represent an accurate translation of a pristine version of Isaiah that was written on metal plates before the fall of Jerusalem.

Rasmussen presented a nice analysis of Wright’s assumptions, although there is no warrant whatsoever for supposing that there was a Hebrew Vorlage on either the Brass Plates or the Gold Plates. The Book of Mormon itself makes clear that the original text was Egyptian in each case — as I point out in my recent book, Egyptianisms in the Book of Mormon and Other Studies (2020), online at https://books.google.com/books/about/EGYPTIANISMS_IN_THE_BOOK_OF_MORMON_AND_O.html?id=y4IdzgEACAAJ .

Thanks Robert. I’d run into your book on Egyptianisms in passing, but I’ll definitely have to give it a longer look.

I’d agree that the Gold Plates wouldn’t have had much if any Hebrew (Grover’s analysis suggests there’s at least some Hebrew calendrical elements), but I’m not sure we can say the same about the Brass Plates. Yes, we’ve found quite a bit of archaeological evidence of Hebrew written in Egyptian script, but most writing in that period was still in Hebrew. Just from a probabilistic perspective, that seems to give us some reason to expect it to have been written in Hebrew, particularly since the BofM doesn’t specify one way or another.

Cheers, and thanks for reading.

I have always wondered how 2 Nephi 12:16 squares with any of these theories, as it has a phrase that appears in the Septuagint but not in the Bible. There was an 1808 English translation of the Septuagint published in America by Charles Thomson, so presumably Joseph Smith would have had access to that, but it seems like we have a hard time proving Joseph even had access to a Bible during translation, let alone the opportunity for a side-by-side comparison to the Septuagint. Furthermore, the inclusion of the Septuagint phrase doesn’t square with Early Modern English evidence, as the first english translation of the Septuagint (as far as I know) was the 1808 version.

Would it even be plausible to conjecture that the Brass Plates, the Septuagint and the KJV are based in the same original text, and if so why does only one (as far as I know) Septuagint-KJV discrepancy show up in the Book of Mormon?

If Joseph Smith, (or other alleged authors) fabricated this, why did they only include one snippet?

Really more questions than answers…

Thanks for the thoughts, Derek.

2 Nephi 12:16 is an interesting problem on both sides, for sure. Wright argues that the presence of both phrases wrecks the poetic structure of the original, and that it’s unlikely that both were present in what Isaiah wrote. But the idea that Joseph just copied from Thomson’s translation has its issues, since Thomson phrases it very differently from the BofM:

“and against every ship of the sea; and against every ensign of beauteous ships”

It would definitely seem odd for Joseph to borrow just that one line, and to borrow it imperfectly.

As you say, more questions than answers.

I remember reading an article by Hugh Nibley (but haven’t been able to locate the article) in which Nibley also points out that where the Isaiah verses in the Book of Mormon differ from the King James Version, that those verses are much more in line with the Septuagint.

You are right, Derek. More questions than answers.