Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the thirteenth in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that the Book of Mormon could have so many examples of chiasmus if it was written by Joseph.

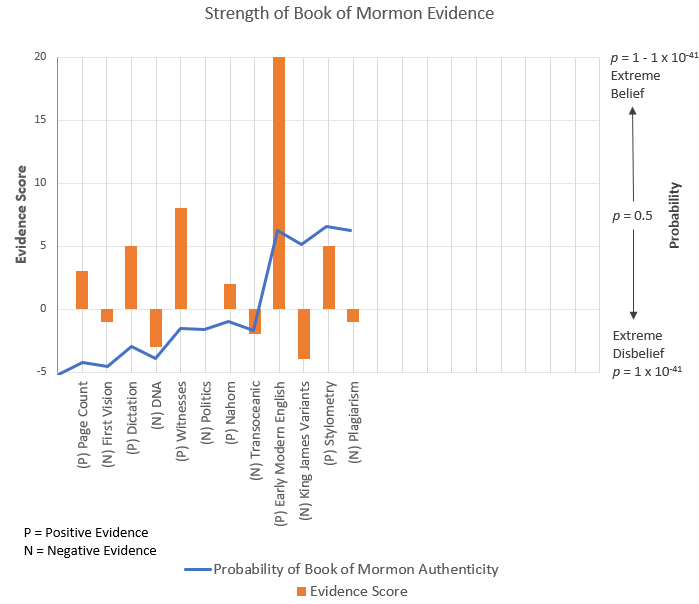

Chiasmus has been a mainstay of Book of Mormon apologetics for more than five decades, but the ease with which chiasmus can be found in just about any book has led some to doubt its utility as evidence for the Book of Mormon. Yet the raw amount of chiasmus in the book is truly prodigious, with hundreds of potential examples just within 1 Nephi. I use a measure of repetition as a proxy for the amount of chiasmus we might expect in the Book of Mormon and other texts. I show that, in that regard, the Book of Mormon is remarkably similar to biblical scripture, and an extremely poor fit for pseudobiblical works from Joseph’s time (p = 3.14 x 10-10). I also incorporate evidence that the Book of Mormon’s ancient poetic forms are distributed in a way that would be unlikely if such had appeared by chance or were a general feature of Joseph’s own writing (p = .000016). Chiasmus remains formidable evidence in the Book of Mormon’s favor.

Evidence Score = 14 (increasing the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon by 14 orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When we last left you, our ardent skeptic, you had decided to set aside two conspicuous books from your collection, and press onward through the other tome that lay open on your table. You turn the pages almost absentmindedly—the story continued through a rather interesting tree-oriented allegory, as well as a very, very long prayer, followed by a set of brief entries by those who seemed to hold very little interest in contributing to the text. An odd choice of narrative structure, to be sure, but you give it little thought as it plods on, verse by verse and book by book.

As you keep reading, you barely notice the light outside beginning to dim, and it’s only reluctantly that you reach to light a nearby candle. The hours had been long, and as the candlelight dances on the page your eyes begin to play tricks, your mind forming shapes and patterns that you knew weren’t there. Your eyes squint involuntarily and you shake your head, and as you again find your place you discover a different sort of pattern—one you definitely hadn’t expected to find in this particular work. The words of the pattern almost jump off the page as you read on:

But men drink damnation to their own souls except they humble themselves and become as little children, and believe that salvation was, and is, and is to come, in and through the atoning blood of Christ, the Lord Omnipotent. For the natural man is an enemy to God, and has been from the fall of Adam, and will be, forever and ever, unless he yields to the enticings of the Holy Spirit, and putteth off the natural man and becometh a saint through the atonement of Christ the Lord, and becometh as a child, submissive, meek, humble, patient, full of love, willing to submit to all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon him, even as a child doth submit to his father.

Like an image that resolves after long-crossed eyes, the pattern of words resolves into a strange structure, an inverted parallel, circling from humble to natural man and back again. The pattern gives your memory a palpable jog—you had heard of this sort of structure before, an obscure form of ancient poetry that had been described only a few years earlier by scholars an ocean away. To find it in the words of an uneducated farm boy was strange indeed.

You suppose that perhaps that farm boy might’ve heard of this structure, or perhaps that it occurred by chance, and content yourself with those thoughts for the moment, ready to move on with your reading. But only a couple chapters later, you’re somewhat surprised to find yet another example of an inverted parallel:

And now, because of the covenant which ye have made ye shall be called the children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters; for behold, this day he hath spiritually begotten you; for ye say that your hearts are changed through faith on his name; therefore, ye are born of him and have become his sons and his daughters.

One example was rather easy dismissed. Two, appearing so quickly, is much more difficult to ignore. You try your best to do so, though, pressing forward with the chapter. Only a few verses later, though, your eyes hit upon yet another such pattern:

And now it shall come to pass, that whosoever shall not take upon him the name of Christ must be called

by some other name; therefore, he findeth himself on the left hand of God. And I would that ye should remember also, that this is the name that I said I should give unto you that never should be blotted out, except it be through transgression; therefore, take heed that ye do not transgress, that the name be not blotted out of your hearts. I say unto you, I would that ye should remember to retain the name written always in your hearts, that ye are not found on the left hand of God, but that ye hear and know the voice by which ye shall be called, and also, the name by which he shall call you.

You turn your eyes away from the book as a sense of frustration fills your mind—these poetic structures seem to be taunting you wherever you turn in the book, and now that you see them, it seems impossible to unsee them. It seems unlikely that a book could be filled with such poetic structures by accident, and unlikelier still for them to have been placed with such prodigious frequency by any modern imitator.

The Introduction

Since the 1960s, critics and faithful scholars alike have had to grapple with the presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon and other Latter-Day Saint scripture. On the one hand, these and other structures characteristic of ancient literary works seem out of place in the writing of Joseph Smith or other nineteenth-century authors given the lack of knowledge they would have had of such structures and their lack of expertise in producing them. Faithful scholars have done a thorough job of documenting these structures and providing arguments for their validity and literary merit, most notably John Welch and Donald Parry. On the other hand, chiastic structures can appear unintentionally in almost any work of a certain length, leading many critics to dismiss chiasmus as either a fluke or as an unconscious characteristic of Joseph’s writing style.

The question, given this debate, is how unexpected chiasmus in the Book of Mormon is given its purported modern and ancient origins. Hopefully Bayesian analysis can help us uncover a few unique insights.

The Analysis

The Evidence

Chiasmus is a literary structure, common in ancient poetry, involving words, concepts, or ideas repeated in reverse order. Though scholars today have little trouble finding numerous examples of chiasmus in biblical contexts, as well as in ancient, archaic, and modern poetry, chiasmus itself wasn’t recognized or described in the modern era until the work of John Jebb and Thomas Boys in England in the 1820s. Since that time there’s been an explosion of scholarship that seems to find chiasmus around every literary corner, and the Book of Mormon has been no exception.

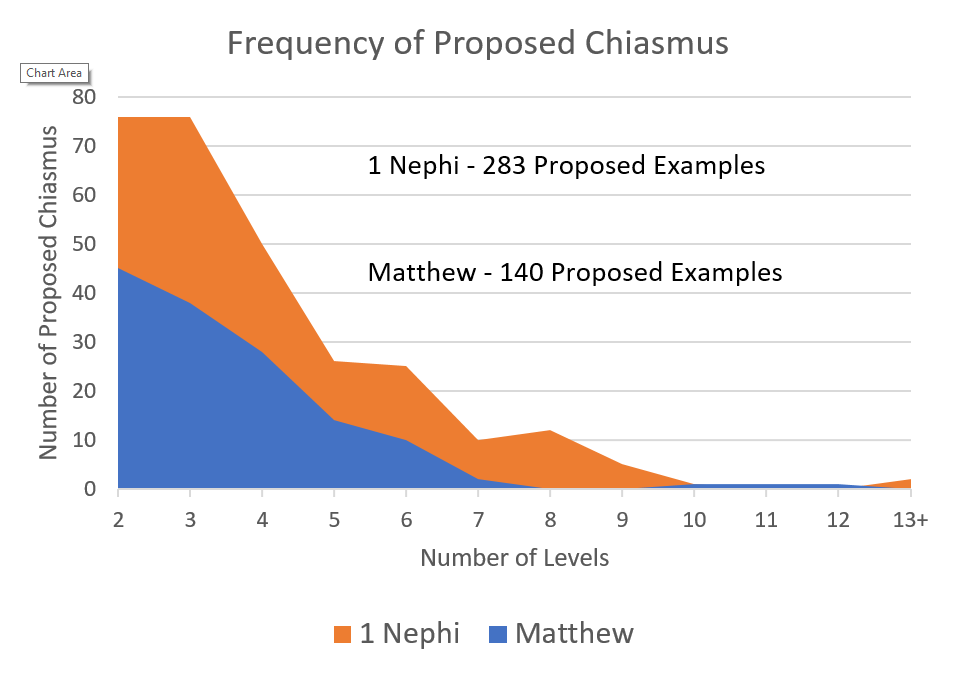

Very few would deny that chiasmus exists in the Book of Mormon. Many readers would be familiar with the extensive chiasm in Alma 36—what could effectively be described as the Book of Mormon’s chiastic crown jewel. Before starting my research for this episode, I’d known generally about chiasmus, but I wouldn’t have been able to identify many other specific cases besides Alma 36. When I looked into it, I was frankly a bit floored by the raw amount of chiastic examples that have been proposed over the years—over 280 potential examples just in 1 Nephi. It’s probably easier to count the verses that haven’t been implicated in a chiasmus than to count the ones that are.

Not all of these are classic examples of the poetic form. Some of the patterns are conceptual and span multiple chapters, and even multiple books. Others include variation or imperfection in the inversion pattern. Literary scholars have even found reason to doubt whether Alma 36 is an intentional chiasm, particularly since there are a number of important and repeated themes in the chapter that weren’t incorporated into the structure (and there’s little agreement on what ultimate form the structure takes). But there are plenty of strong examples that are more difficult to criticize, including some of the ones detailed above.

The question is whether it would be unusual to find chiasmus in a book like the Book of Mormon, if someone like Joseph Smith had written it. The general tack taken by the critics is to offer counter-examples of chiasmus in contexts where it was certainly not intended, from pseudobiblical works to Dr. Seuss to modern technical manuals. Many books have repeated elements, and with enough repetition it’s only a matter of time before a chiasmus presents itself on the basis of chance alone.

And that fact is worth emphasizing—chiasmus depends on repetition. Where repetition is found, chiasmus will follow. Consequently, where more repetition is found, you’ll be more likely to find chiasmus.

I’m not the first to realize that fact or to try to calculate the probability of encountering chiasmus in a given text by chance. Boyd and Farrell Edwards, a father and son duo of physics professors operating out of Utah State University, took up that problem in a paper published in BYU Studies in the mid 2000s. Specifically focusing on the chiasm in Alma 36, along with a few other prominent examples, they assessed how likely it would be for chiasmus of different levels to appear given an estimated amount of repetition of words or concepts, as well as the length of the text. Using their own proposed 9-level structure for Alma 36, they estimated the probability of those concepts appearing by chance in inverse-parallel order at p = .00000049. Assuming that each Alma 36-size section of the book represented an independent chance for that size of chiasmus to appear, that would mean the overall probability of that type of chiasm appearing at any point in the book is p = .00018. To them, this was a strong indication that Alma 36 was an intentional chiasm, rather than one that appeared accidentally.

Despite some criticism of their (and others’) handling of the chiasm in Alma 36, the statistical point still stands—it’s very unlikely that the ordering of elements in Alma 36 is accidental. Though this helps us place more confidence that Alma 36 has intentional poetic meaning, worthy of literary merit (a point further strengthened in a recent Interpreter article by Noel Reynolds), it doesn’t fully resolve the question of authenticity. Even though Joseph Smith likely knew little if anything about chiasmus, it’s difficult to rule out his intentional (if unknowing) creation of an inverted parallel in these or other isolated cases (though you could still argue that this intentionality is unexpected enough to count in the Book of Mormon’s favor—if you’re wondering how I’ll be exercising a fortiori reasoning in this episode, it’ll be by not incorporating this analysis into my probability estimates).

So we’ll be taking a different tack than did the Edwards. Rather than ask how likely it would be to find one specific chiasmus out of the hundreds in the Book of Mormon, we’ll consider whether we should expect to find those hundreds in the first place.

We’ll also be considering the distribution of chiasmus in the book. One analysis by Carl Cranney divided various sections of the Book of Mormon into those that would’ve been delivered orally (i.e., its sermons) and those that would’ve been originally delivered via written text (i.e., in letters), and then counted the proportion of those sections that contained chiasmus and other forms of parallelism. As chiasmus is generally meant to be conveyed orally, one would expect sermons to be more likely to contain these poetic elements than written letters, which is exactly what Cranney found. Approximately 52% of the oral texts were implicated in parallelistic elements, while only about 14% of the written texts were. Though the sample of texts was relatively small (10 in each group), the difference was more than enough to reach statistical significance, at t(18) = 5.84, p = .000016. We’ll need to think through whether and how to incorporate this evidence into our overall estimate.

The Hypotheses

Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon is due to ancient writing patterns and techniques—According to this hypothesis, chiasmus is in the Book of Mormon because ancient authors put it there, either intentionally through the deliberate crafting of chiastic patterns or unintentionally as a consequence of ancient literary habits.

Now, hold on here, did I just say that unintentional chiasmus can still count in favor of the Book of Mormon? Yes, yes I did, and here’s why.

For one, when it comes to the question of authenticity, it doesn’t matter what the authors’ intention is—the only thing that matters is whether it’s ancient or modern. Lots of the evidence we’ve considered so far is unintentional, whether it’s the word pattern ratios used by particular authors or the Early Modern nature of syntax, grammar, and vocabulary. Unintentional patterns actually have the advantage of being more difficult to discover and recognize, and thus more difficult to fake.

For another, it’s clear that not all chiasmus is intentional, even in authentic ancient documents. It’s hard to imagine the author of Matthew, for example, taking the time to deliberately craft nearly 150 examples of chiasmus. As I’ve noted, chiasms could form purely on the basis of chance—chiasmus depends on repetition, and enough repetition, over time, will create chiastic patterns. But there are a lot of factors that serve to increase that repetition. For instance, some languages have a relatively limited vocabulary, and thus naturally feature more repetition, just by having fewer words to work with. There might also be other (non-chiastic) linguistic forms that also depend on repeated concepts, such as parallelism.

In addition, it’s possible that the chiasmus is intentional, but not the way we usually think. Chiasmus may not always require that an author take the time to deliberately put together each piece of the chiasmus, embedding within it deep poetic meaning. It might instead be formed simply on the basis of convention. Take periods, for example. When I put a period at the end of a sentence, sometimes I do so deliberately. But most of the time I put it there because modern writing conventions tell me that I should. The period has meaning, but only on the basis of agreed-upon (and usually unwritten) rules—rules that we learn and that eventually become ingrained in our writing style. I don’t have to take the time to think about the placement of my periods, and they usually don’t carry any broader poetic meaning. Most of the time, a period is just a period.

Something similar could apply to chiasmus. Perhaps, to ancient writers, a thought just didn’t sound right unless it was repeated in reverse order. If so, chiasmus would end up appearing very frequently throughout a text, and authors would be so practiced at it that they wouldn’t have to spend much time putting them together. There wouldn’t necessarily be any deeper literary meaning locked within, any more than we’d expect deeper meaning in commas or periods.

Between those three—chance, convention, and non-chiastic writing patterns—we have an explanation for the large frequency of chiasmus we find in both biblical scripture and the Book of Mormon. There would still be room for ancient authors to craft beautiful, meaningful chiasms, such as Alma 36. But many—if not most—would be there either unintentionally or without deliberate literary intent. And notably, if any of those sources of chiasm are specific to ancient writing, they would serve as a valid means of testing the book’s authenticity. In short, if the Book of Mormon is authentically ancient, it should have comparable rates of chiasmus to other authentically ancient works, such as the Bible.

So that is a roundabout way of forming our first hypothesis. What about the second?

Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon can be attributed to modern authorship—With this hypothesis, chiasmus could appear in the same general ways as they might with ancient authorship—that is, intentionally or unintentionally. If Joseph or someone else in the nineteenth century wrote the Book of Mormon, he would either do so intentionally or unintentionally, due to chance or convention. But in both cases we would expect a far lower frequency of chiasmus within the text compared to ancient sources. As unpracticed as Joseph would have been in creating chiasmus, it’s unlikely that he would be able to do so at such a prodigious rate, particularly when dictating the text. And it’s clear that chiasm is not a convention of modern writing, nor is modern writing characterized by the ancient literary patterns that could otherwise give rise to unintentional chiasms.

Because of this, if the Book of Mormon is a modern book, it should contain about as much chiasmus as other modern books, including books that attempt to replicate biblical style. Also, any examples of chiasmus or parallelism that we did find (either through chance or through the writer “having an ear” for biblical poetic forms) should be randomly distributed throughout the text. Anything else would be, dare I say it, unexpected.

Prior Probabilities

Here’s a reminder of where the evidence stands so far:

PH—Prior Probability of Ancient Authorship—Our initial estimate of probability of the Book of Mormon’s authenticity remains where we last left it, at a value that’s starting to get within striking distance of the tipping point of .5, p = .0000779.

PA—Prior Probability of Modern Authorship—Conversely, our estimate of the probability of modern authorship stands at p = .9999221.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—So how likely would we be to observe the amount of chiasmus we do in the Book of Mormon if it’s truly ancient scripture? Well, the best way to figure that out would be to count the number of examples of chiasmus we find in the Book of Mormon, and then compare it to the number we find in ancient scripture, with the Bible being the obvious comparison. At first glance that seems like a doable thing to do—as we’ve noted, Jack Welch has devoted his life to documenting every known example of chiasmus in a variety of different sources, including the Book of Mormon and the Bible.

I even took a stab at making those comparisons, throwing each example and the number of levels of the chiasmus into a spreadsheet. But a few things became clear pretty quickly:

- Ain’t nobody got time for that. As an amateur analyst doing this in my spare time, extracting that kind of data in the time I allot for these episodes would’ve been damaging to my sanity. I managed to get through 1 Nephi and the book of Matthew, but that alone took hours; there were over 500 examples to go through in those two books alone. If I was a full-time researcher with a small army of starving students at my disposal it wouldn’t be that bad, but that wasn’t in the cards.

- The data itself is messy. Welch’s database is fastidious and extremely useful, but it’s hard to know how comparable these examples are. In the case of the Book of Mormon you have a number of different analysts analyzing the book, picking out examples based, in many cases, on their own idiosyncratic criteria, and who often disagree with each other about the exact form and extent of each chiasm. In the case of the Bible you have hundreds of people who have worked through the text with a fine-tooth comb without any consistent methodology. Welch has worked to establish a set of useful ways to separate the wheat from the chaff, but even those criteria need to be subjectively applied. A valid analysis would’ve required carefully reading through each example and trying to judge the quality of the chiasmus—an effort that could easily take several lifetimes and that would ultimately represent little more than my own opinion.

- The chiasmus database doesn’t cover more modern works from Joseph’s day. I might have been able to do something workable using the data I extracted from 1 Nephi and Matthew—it seems, for instance, that 1 Nephi has a surprising amount of chiasmus in comparison to the New Testament (see the figure below). But that wouldn’t have helped me when it came to the really interesting comparisons I needed to make down the road when testing the hypothesis of modern authorship. Some people have cherry-picked examples of chiasmus from, say, The Late War, but no one’s done the truly thorough search for chiasmus in modern books that’s been done for the Bible and the Book of Mormon. To conduct any sort of valid comparison I would’ve needed to do that myself, and I can think of better uses of my time than poring through the First Book of Napoleon looking for inverted parallels.

I thought I was up a creek for a while there, but a little perseverance led me down a more promising path. We can’t get a solid count of chiasmus for our analysis, but is there a way to estimate how much chiasmus we’d find? Better yet, is there an analysis we could use that doesn’t take a ton of time and that isn’t quite as subjective as the process of searching for chiasmus itself?

If we can’t access chiasmus, can we access the phenomenon that gives rise to it—the repetition of words, ideas, and concepts?

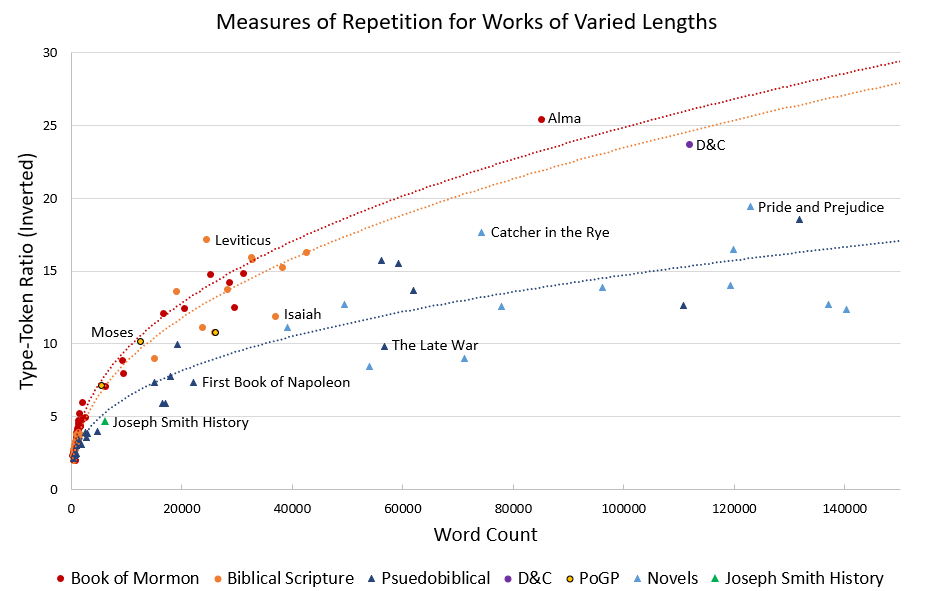

Turns out that we can. Quantitative linguists have long used a measure of repetition as a meaningful characteristic to distinguish between different forms of literature. That measure is the Type-Token Ratio (TTR), or the ratio of the total number of unique words in a text (types), to the total number of raw words in that text (tokens). It’s essentially a way to assess the working vocabulary of the author—the higher the vocabulary, the more unique words you’ll find relative to a text’s total word count. But it also works to measure repetition—the more repetitive a text is, the fewer unique words you’ll find. It’s also exceptionally easy to calculate if you have the software necessary to count the number of unique words in each text.

For example, 1 Nephi has a total word count of 25,126 as measured by WordCruncher, but only has 1,699 unique words. We can calculate the TTR by dividing the number of unique words by the total word count, which would be 1699/25126 = 0.07. You could compare that to a modern book, such as our good friend The Late War, which only has about twice the total word count (56,632), but over triple the number of unique words (5,749), creating a substantially higher TTR (0.10).

For our purposes here, though, we want higher TTR values to represent more repetition (which might indicate more chiasmus). To do that, we’re going to invert our TTR values to create an “Inverted TTR” measure. Doing this doesn’t change the results at all, it just helps it match what we’re actually trying to measure. In the cases above, we’d end up with values of 14.8 and 9.85 for 1 Nephi and The Late War, respectively, indicating that 1 Nephi shows more repetition than The Late War.

Now, whether or not we invert it, the TTR is a bit of a tricky measure. For one, our ratios are much lower for longer texts than for shorter ones. This makes intuitive sense—the longer the text is, the less likely you’ll be to run into unique words, even if the vocabulary is about the same. That issue means you can’t just compare the ratio for the Book of Mormon to, say, the Old Testament—since the Old Testament is more than twice as long, the values themselves aren’t comparable. But it turns out that the ratio does tend to follow a pattern. If you plot different portions of a text (of different sizes) by both the TTR and the overall word count, it tends to follow a logarithmic curve.

You can see what I mean in the figure above. In that figure I’ve calculated an inverted TTR for both Book of Mormon texts of various sizes (verses from 1 Nephi, and the different books themselves), and texts of biblical scripture (verses from Matthew, the books of the Gospels, the Pentateuch, and Isaiah and Jeremiah). I then let Excel draw a logarithmic line of best fit through each, which are the red and orange lines respectively. The higher a curve is on the graph, the more repetition occurs in the text (fewer unique words relative to the total word count). You’ll notice that the Book of Mormon texts and the biblical texts closely fit their respective lines, and, importantly, that they’re fairly close to each other. This means that, though there’s some variation (note that Leviticus, for example, has substantially more repetition than Isaiah; it’s also not a coincidence that Leviticus is famous for its prolific examples of chiasmus and parallelism), the Book of Mormon and the Bible have similar levels of repetition, suggesting that we should be about as likely to see chiasmus (whether intentional or unintentional) in both (interestingly, you’ll notice that the D&C, as well as the books of Moses and Abraham from the Pearl of Great Price also fit well with other books of scripture).

Getting a decent probability estimate out of that is a fairly straightforward procedure. I used a variation of a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to see if there were substantial differences between the two sets of scriptural texts, the same way scientists test for differences in two different treatment groups in an experiment. ANOVA uses variation around means to test those differences—it calculates the mean for each group independent of each other (group means), as well as the mean for all observations regardless of group (the grand mean). The test compares how group means differ from each other relative to what we’d expect given how variable the observations are generally (around the grand mean), using an F-statistic to get a probability estimate for the hypothesis that the two groups are the same. I did the same thing, except instead of using means, I used the curves of best fit from the Excel chart. I calculated the variation of each group of texts (just the books, not individual chapters) around their respective lines, and compared it to the variation around a separate line of best fit (not shown in the figure) describing all the scriptural texts as if they were a single group. You can see the full list of works and their respective word count measures in the Appendix, along with the equations for those curves, and you can see the relevant calculations for the ANOVA below.

| Book of Mormon — Bible ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares Within (SSW) | 66.10 | F (MSB/MSE) |

| Sum of Squares Total (SST) | 69.43 | 1.21 |

| Sum of Squares Between (SSB; SST – SSW) | 3.33 | |

| Mean Square Between (MSB; SSB/(k-1)) | 3.33 | p |

| Mean Square Error (MSE; SSW/(N-k)) | 2.75 | 0.28 |

| k (number of groups) | 2 | |

| N (number of observations) | 26 | |

Overall, not only do those lines of best fit seem close to each other, they actually are close in a statistical sense, with the probability that they belong to the same category estimated at p = .28; F(1,24) = 1.21. That’s the estimate we’re going to use for the consequent probability of ancient authorship.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—But how likely would we be to observe that level of repetition if the Book of Mormon was a modern text? Thankfully, we have plenty of examples of modern books that we can compare it to, including books from the nineteenth century that attempted to emulate a biblical style. You’ll see those examples plotted in the figure as well, including modern novels (e.g., Pride and Prejudice and Lord of the Rings) and a variety of pseudobiblical texts. Notice that none of them reach the same level of repetition that we see in the Bible and the Book of Mormon (the closest, interestingly enough, is Catcher in the Rye; also note that Joseph Smith—History fits very well with these modern texts). Based on this, it follows that we’d be less likely to see any kind of chiasmus or parallelism within these texts (though we’d still see some, particularly in the longer texts) than we would in the texts that are actually scriptural.

We can also do the same statistical test as above, comparing these modern texts, specifically the nineteenth-century pseudobiblical texts (of which there were 25, of varying lengths), to the Book of Mormon. How likely is it that the Book of Mormon belongs with these pseudobiblical texts? As you could probably tell by looking at the blue line of best fit, not very. In terms of the results of the statistical test, though, “not very” is a substantial understatement. It’s extremely unlikely that the books belong in the same category, with p = 3.14 x 10-10; F(1,38) = 71.1.

| Book of Mormon — Pseudobiblical ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares Within (SSW) | 84.83 | F (MSB/MSE) |

| Sum of Squares Total (SST) | 243.45 | 71.06 |

| Sum of Squares Between (SSB; SST – SSW) | 158.62 | |

| Mean Square Between (MSB; SSB/(k-1)) | 158.62 | p |

| Mean Square Error (MSE; SSW/(N-k)) | 2.23 | 3.14 x 10-10 |

| k (number of groups) | 2 | |

| N (number of observations) | 40 | |

It’s fair to ask why the modern texts would have so little repetition. Yes, they don’t share the same conventions as ancient literature, and are unlikely to deliberately produce the chiasmus or parallelism we see in the biblical texts. But it’s more than that. As mentioned above, English is a high-vocabulary language. English is an eclectic and unusual mix of Germanic, Latin, and Scandinavian languages that has absorbed thousands of words of foreign origin over the centuries. We have words for everything, and usually a substantial number of words for each individual something. It’s not surprising that the modern texts, all written in English, would have a relatively large number of unique words, and that the biblical texts, written in relatively less-developed ancient Hebrew and Greek, would have relatively few.

But then what about the Book of Mormon, the D&C, and the Pearl of Great Price? This is a bit of conjecture on my part, so be warned. But it’s possible that such repetition is an indication that these texts weren’t actually composed in English. That would make fine enough sense if the books are authentic, but would be rather surprising if they were modern texts written by the decidedly uni-lingual (at the time) Joseph Smith.

Regardless, we have what we need to wrap up our analysis. Before we do, though, we’ll need to consider how to incorporate the findings from the Cranney article, which found that chiasmus and parallelism were much more likely to be found in Book of Mormon texts that would’ve been delivered orally than in its written texts. The main question here is one of independence—would we expect the frequency of chiasmus in a text (as indicated by the TTR) to be independent of how those texts are distributed within the text? Hopefully this is something on which reasonable people can agree—merely inserting more instances of chiasmus into a text should have nothing to do with putting those instances in the right spots and in the right context—in fact, doing so naively might lead to those instances being scattered indiscriminately through the text. If so, then these two pieces of evidence can be considered to be independent, and we can incorporate that evidence by multiplying the p-value calculated by Cranney (p = .000016) by the p-value for the TTR comparison that we’ve calculated here (p = 3.14 x 10-10). That would leave us with a final consequent probability estimate of p = 5.02 x 10-15.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon, given the evidence we’ve considered so far, or p = .0000779)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the probability of modern authorship, given that earlier evidence, or p = .9999221)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our estimate of the probability of observing the amount of repetition we see in the Book of Mormon, if it represents authentic ancient scripture, or p = .28)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our estimate of the likelihood of observing that repetition, if the book is a modern pseudobiblical text, or p = 5.02 x 10-15)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (our new estimate of the probability of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = .0000779 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (.0000779 * .28) |

| (.0000779 * .28) + (.9999221 * 5.02 x 10-15) | |

| PostProb = | 1 – 2.3 x 10-10 |

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH/CA)

Lmag = log10(.28/5.02 x 10-15)

Lmag = log10(5.57 x 1013)

Lmag = 14

Conclusion

That’s enough to place the chiasmus-related evidence into pole position alongside our other evidence—not a critical strike, by any means, but still prompting a substantial shift in favor of authenticity. And importantly, our view of the Book of Mormon has finally flipped on its head, moving from a still-small probability of .0000779 to a surprisingly confident .99999999977. Many faithful scholars have long seen chiasmus and other assorted ancient literary structures as formidable evidence on the side of the Book of Mormon, and this analysis does nothing to change that perception. Critics can chip away at individual examples of chiastic structure all they like, but the raw repetition (and distribution) undergirding those structures is both a good match for biblical scripture and thoroughly unexpected from the standpoint of modern authorship, especially from a young, first-time author.

Skeptic’s Corner

Since I’m the first person to mess around with the idea of using the TTR as a proxy-measure for chiasm and parallelism, it goes without saying that these results are tentative and exploratory. As interesting as these results may be, there would be a ton of ways to improve it. For one, I could repeat the analysis using all the books of the Bible rather than the select few I used here. I could also account for common words, such as articles and prepositions (e.g., “a”, “the”), or the unusual personal and place names in the Book of Mormon. Then I could look at removing all the different KJV quotations from the Book of Mormon to see what stands on its own, though this would be unlikely to help the cause of the critics (Isaiah is one of the least repetitious books that we analyzed, while Alma, which has relatively few quotations, has some of the most repetition). Do I think this would alter the analysis much? Probably not. But it would be a start toward making this a scholarly effort worthy of mainstream publication.

The biggest limitation here, though, is the lack of an explicit connection between the TTR and the actual amount of Hebrew poetic structures in the text. The connection was assumed (with good reason) but not actually measured. A validation study that actually tries to count the number of poetic structures and correlating that with the TTR would be a vital step here, though it would take work that I didn’t have time for and likely will never have available.

It would also be worth looking a bit deeper into the question of the distribution of chiasms. Do biblical texts show the same relative distribution when comparing oral and written texts? If circumstances had allowed Joseph to somehow read up on chiasmus while he was writing the Book of Mormon, would he have known to stick those chiasms primarily within sermons? Both of these are valid questions. But for the moment we move on, content to have documented another means by which the Book of Mormon appears out of place in a nineteenth-century context.

Next Time, in Episode 14:

When next we meet, we’ll be digging into the archaeological arguments surrounding the Book of Mormon, both for and against.

Questions, ideas, and foreboding chills can be run down the spine of BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below. Bonus friend-points for anyone who can locate examples of chiasmus in this essay!

Many thanks to Stanford Carmack for use of his WordCruncher package containing the 25 pseudobiblical texts included in the analysis.

Appendix

| Source | Book | Unique Words | Total Words | TTR (Inverted) |

Within | Between – BofM/Bible | Between – BofM/Pseudo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Residual2 | Predicted | Residual2 | Predicted | Residual2 | |||||

| Bible | Matthew | 2130 | 23684 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 2.4 | 12.9 | 3.2 | ||

| Bible | Mark | 1679 | 15166 | 9.0 | 10.5 | 2.0 | 10.7 | 2.7 | ||

| Bible | Luke | 2398 | 25938 | 10.8 | 13.2 | 5.5 | 13.4 | 6.8 | ||

| Bible | John | 1401 | 19094 | 13.6 | 11.5 | 4.3 | 11.8 | 3.4 | ||

| Bible | Genesis | 2511 | 38263 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 0.1 | 15.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Bible | Exodus | 2050 | 32686 | 15.9 | 14.5 | 2.0 | 14.8 | 1.3 | ||

| Bible | Leviticus | 1430 | 24541 | 17.2 | 12.9 | 18.5 | 13.1 | 16.4 | ||

| Bible | Numbers | 2084 | 32896 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 1.5 | 14.9 | 0.9 | ||

| Bible | Deuteronomy | 2059 | 28352 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 0.0 | 13.9 | 0.0 | ||

| Bible | Isaiah | 3118 | 37036 | 11.9 | 15.3 | 12.0 | 15.6 | 14.0 | ||

| Bible | Jeremiah | 2619 | 42654 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 0.0 | 16.6 | 0.1 | ||

| BofM | 1 Nephi | 1699 | 25126 | 14.8 | 14.1 | 0.5 | 13.2 | 2.4 | 10.4 | 19.1 |

| BofM | 2 Nephi | 2352 | 29419 | 12.5 | 15.0 | 6.3 | 14.2 | 2.7 | 11.1 | 2.0 |

| BofM | Jacob | 1026 | 9131 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 0.1 | 8.6 | 0.1 | 7.0 | 3.5 |

| BofM | Enos | 358 | 732 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| BofM | Jarom | 267 | 1398 | 5.2 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| BofM | Omni | 349 | 1160 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| BofM | Words of Mormon | 234 | 857 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 0.8 |

| BofM | Mosiah | 2095 | 31151 | 14.9 | 15.4 | 0.3 | 14.5 | 0.1 | 11.3 | 12.5 |

| BofM | Alma | 3344 | 85032 | 25.4 | 23.3 | 4.7 | 22.3 | 10.0 | 16.8 | 74.8 |

| BofM | Helaman | 1632 | 20402 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 0.2 | 12.1 | 0.2 | 9.6 | 8.4 |

| BofM | 3 Nephi | 2006 | 28636 | 14.3 | 14.8 | 0.3 | 14.0 | 0.1 | 11.0 | 10.9 |

| BofM | 4 Nephi | 404 | 1946 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 3.8 | 1.0 |

| BofM | Mormon | 1178 | 9437 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 0.5 | 7.1 | 0.8 |

| BofM | Ether | 1374 | 16627 | 12.1 | 11.9 | 0.1 | 11.1 | 1.0 | 8.9 | 10.4 |

| BofM | Moroni | 862 | 6116 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 0.6 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 1.2 |

| Pseudo | Chronicle of the Kings of England | 2789 | 16465 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 8.6 | ||

| Pseudo | The Book of Jasher | 1935 | 19279 | 10.0 | 7.7 | 5.3 | 9.4 | 0.3 | ||

| Pseudo | American Chronicles | 2878 | 17012 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 2.0 | 8.9 | 9.2 | ||

| Pseudo | The American Revolution | 3563 | 56172 | 15.8 | 11.3 | 20.1 | 14.3 | 2.2 | ||

| Pseudo | The First Book of Napoleon | 2999 | 22118 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 0.5 | 9.9 | 6.5 | ||

| Pseudo | History of Anti-Christ | 2052 | 15057 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 0.1 | 8.5 | 1.4 | ||

| Pseudo | The Late War | 5749 | 56632 | 9.9 | 11.3 | 2.1 | 14.3 | 19.9 | ||

| Pseudo | Chronicles of Eri | 7103 | 131741 | 18.5 | 15.4 | 10.2 | 19.9 | 1.9 | ||

| Pseudo | The Epistles of Ignatius and Polycarp | 2323 | 18058 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 9.2 | 1.9 | ||

| Pseudo | Sacred Roll | 4520 | 61889 | 13.7 | 11.7 | 4.0 | 14.8 | 1.3 | ||

| Pseudo | The Healing of the Nations | 8779 | 110871 | 12.6 | 14.4 | 3.2 | 18.6 | 35.8 | ||

| Pseudo | The New Gospel of Peace | 3809 | 59162 | 15.5 | 11.5 | 16.3 | 14.6 | 0.9 | ||

| Pseudo | Book of Preferment | 760 | 2731 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.6 | ||

| Pseudo | The French Gasconade Defeated | 295 | 902 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 0.0 | ||

| Pseudo | Parable Against Persecution | 186 | 402 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 0.0 | ||

| Pseudo | Chronicles of Nathan Ben Saddi | 778 | 2999 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 0.5 | ||

| Pseudo | Samuel the Squomicutite | 247 | 605 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | ||

| Pseudo | The Book of America | 653 | 2562 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 4.3 | 0.1 | ||

| Pseudo | Chapter 37th | 251 | 611 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | ||

| Pseudo | Chronicles of John | 341 | 828 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.1 | ||

| Pseudo | The First Book of Chronicles, Chapter the Fifth | 587 | 1830 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 0.4 | ||

| Pseudo | Chronicles of Andrew | 1206 | 4790 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 5.5 | 2.2 | ||

| Pseudo | A Chronicle of the Chiefs of Muttonville | 377 | 933 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.2 | ||

| Pseudo | Reformer Chronicles | 295 | 680 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.1 | ||

| Pseudo | Chronicles of the Land of Gotham | 374 | 1281 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.0 | ||

Values for Modern Non-Pseudobiblical Books

| Book | Unique Words | Total Words | TTR (Inverted) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Separate Peace | 6418 | 54050 | 8.4 |

| The Outsiders | 3898 | 49444 | 12.7 |

| Catcher in the Rye | 4206 | 74193 | 17.6 |

| Pride and Prejudice | 6323 | 122880 | 19.4 |

| Officer’s Daughter | 11308 | 140245 | 12.4 |

| Sense and Sensibility | 7265 | 119893 | 16.5 |

| A Tale of Two Cities | 10778 | 137137 | 12.7 |

| Adventures of Tom Sawyer | 7896 | 71122 | 9.0 |

| The Hobbit | 6911 | 96072 | 13.9 |

| The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe | 3520 | 39166 | 11.1 |

| Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone | 6185 | 77883 | 12.6 |

| Twilight | 8507 | 119270 | 14.0 |

Additional Word Count Measures Used in Figure

| Book | Chapter | Distinct Word Count | Word Count | TTR (Inverted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Nephi | 1 | 265 | 907 | 3.42 |

| 2 | 252 | 879 | 3.49 | |

| 3 | 254 | 1066 | 4.20 | |

| 4 | 316 | 1262 | 3.99 | |

| 5 | 231 | 761 | 3.29 | |

| 6 | 86 | 202 | 2.35 | |

| 7 | 245 | 992 | 4.05 | |

| 8 | 278 | 1221 | 4.39 | |

| 9 | 98 | 259 | 2.64 | |

| 10 | 285 | 918 | 3.22 | |

| 11 | 275 | 1315 | 4.78 | |

| 12 | 217 | 860 | 3.96 | |

| 13 | 314 | 1896 | 6.04 | |

| 14 | 282 | 1283 | 4.55 | |

| 15 | 330 | 1485 | 4.50 | |

| 16 | 371 | 1632 | 4.40 | |

| 17 | 507 | 2523 | 4.98 | |

| 18 | 305 | 1216 | 3.99 | |

| 19 | 335 | 1291 | 3.85 | |

| 20 | 237 | 697 | 2.94 | |

| 21 | 306 | 955 | 3.12 | |

| 22 | 345 | 1506 | 4.37 | |

| Matthew | 1 | 173 | 473 | 2.73 |

| 2 | 207 | 619 | 2.99 | |

| 3 | 192 | 387 | 2.02 | |

| 4 | 224 | 557 | 2.49 | |

| 5 | 317 | 1081 | 3.41 | |

| 6 | 241 | 794 | 3.29 | |

| 7 | 228 | 626 | 2.75 | |

| 8 | 271 | 773 | 2.85 | |

| 9 | 291 | 837 | 2.88 | |

| 10 | 298 | 919 | 3.08 | |

| 11 | 261 | 668 | 2.56 | |

| 12 | 337 | 1168 | 3.47 | |

| 13 | 351 | 1367 | 3.89 | |

| 14 | 261 | 721 | 2.76 | |

| 15 | 280 | 785 | 2.80 | |

| 16 | 241 | 688 | 2.85 | |

| 17 | 248 | 620 | 2.50 | |

| 18 | 275 | 869 | 3.16 | |

| 19 | 246 | 719 | 2.92 | |

| 20 | 244 | 779 | 3.19 | |

| 21 | 339 | 1126 | 3.32 | |

| 22 | 286 | 828 | 2.90 | |

| 23 | 286 | 833 | 2.91 | |

| 24 | 336 | 1047 | 3.12 | |

| 25 | 264 | 995 | 3.77 | |

| 26 | 426 | 1625 | 3.81 | |

| 27 | 400 | 1359 | 3.40 | |

| 28 | 182 | 421 | 2.31 | |

| D&C and Pearl of Great Price |

D&C | 4721 | 111912 | 23.71 |

| Moses | 1230 | 12540 | 10.20 | |

| Abraham | 769 | 5506 | 7.16 | |

| Joseph Smith-History | 1290 | 6071 | 4.71 | |

| PoGP | 2411 | 26045 | 10.80 |

Equations for Curves of Best Fit

| Bible | 0.1696(X)^.4282 |

| BofM | 0.2154(X)^.4125 |

| Psuedo | 0.2153(X)^.362 |

| BofM/Bible | 0.1757(X)^.4266 |

| BofM/Psudo | 0.1992(X)^.3906 |

Having enjoyed the dialogue between the “designated hitter” for the opposing team, Billy Shears, and the erstwhile proponents of the series, Dr. Kyler Rasmussen and Bruce Dale, I have come more than once to the conclusion that there is a form of “desperation” going on in the corner of the opposing council and a firm, convincing determination proffered from the proponents.

I am not a mathematician, a statistician nor very bright in any regard and yet I understand things once they’re explained simply to me. The simple explanations proffered within the article and in the adjoining comments have been sufficiently exculpatory in explaining the reasoning behind the processes involved in the statistical analysis.

I have to laugh when someone insists that an “equal” sign must be left in place when it is thoroughly obvious, (once so reasonably explained) why that equal sign would be nonsensical to the proposition. This becomes even more ludicrous when we realize through the proffered example found within the comment section why and how the reasoning would correlate to other real-world examples (the example of correlating exactly 6′ 7″ babies immediately comes to mind. The poor fit and lack of adequate qualifying data would make the entire statistical model ridiculously worthless…)

It might be beneficial to include that sort of explanation with precisely that example or a similar one as rationale within the body of the article. At least it might redirect or derail anyone who thinks they can “throw-out” the equation by proposing a similar argument as to the virtue of having “equal” as opposed to “greater-than signs” as their supposed evidence of poor analysis.

I really have to agree with Dr. Rasmussen’s determination of the probability of ancient writers “thinking” in a chiastic-style, one that we wouldn’t necessarily understand nor expect today.

I am a firm believer that far too often, we of the present-day enforce or at least “try” to enforce our mindset, –our approved and acknowledged way of thinking– upon ancient people; especially when we do so upon ancient authors or orators.

We tend to think that everyone, in every era, has basically been, acted and thought as we do. For instance, when Chiasms were first becoming more widely known, they were extraordinarily unexpected. Now that we’ve had fifty some-odd years to think about them, we “expect” them less unexpectedly. In other words, they’ve become commonplace to us, so much so that we no longer see them as being a really unusual method of communicating. We have forgotten how unusual they actually were when we first started discovering them. And yet to an ancient orator’s mind who spent much more of his time speaking than any modern speaker, –excepting perhaps certain college professors– chiasms, parallelisms and other oratorical devices were not only common, but probably exactly how the ancient orator/author’s mind functioned.

Also, Dr. Rasmussen mentioned that comparable rates between the Book of Mormon and ancient writings should be somewhat expected… but the corollary is also true and perhaps even more important and pertinent to this discussion: IF… I repeat, IF the Book of Mormon had little or no chiastic structure, then most assuredly we (perhaps us believers, but more assuredly the critics) would see this as a discrepancy in the book. I mean, think about it this way, for one hundred and fifty years, the critics could care less that chiasm was or was not found in the Book of Mormon, because no one knew or cared about it. Once Chiasm was discovered in the Bible, they would have made a huge, big stink if it weren’t likewise found in the Book of Mormon. On the other hand, no wonder we (the books believers) began to and continue to make such a big deal of the fact that it is found in the Book of Mormon.

If the Book of Mormon had little or no chiastic structure, we would have to assume that if that chiastic/parallel structure were missing, it would have to be due to the fact that this technique was not readily known in 1828. This would have pointed directly to Joseph Smith authorship and would have been far more deleterious to the claims of the record than is the fact that they are found, and found almost incidentally, coincidentally and apparently specifically and purposefully in more instances than accidental inclusion can account for.

“It would be helpful for you to substantiate these claims, and I think you would’ve if you could.”

And I did. See my comments here: https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/comments-page/?id=22696

“Chi-squares and t-tests and ANOVAs are pretty good at producing those sorts of probability estimates, and they’re important for hypothesis testing. It’s an acknowledgement that the result might have turned out differently on the basis of chance alone, and that chance could not only have produced a specific F or chi-square, but also an F or chi-square that was even larger than what this specific test produced.”

Those concepts are all from the paradigm of Fisherian statistics. They are not from the paradigm of Bayesian statistics. You need to choose one statistical framework or the other. The way you are combining them is invalid. Call me pedantic if you must, but statistical models must be used properly to have valid results. I don’t divide by zero. When calculating the area of a circle I insist on using the formula pi*r^2 and not 2*pi*r. I calculate the slope of a curve with derivatives and not integrals. And I insist on using Bayes’ Theorem properly and not plugging in numbers from an incompatible statistical paradigm. If that means I’m pedantic, then I plead guilty as charged.

You seem to think Bayes’ Theorem is an arbitrary formula for combining probabilities from various tests. That simply isn’t true. Bayes’ Theorem is an actual mathematical theorem. My formulation is called Bayes’ Theorem and can be mathematically proven true. Your formulation is not Bayes’ Theorem and can be mathematically proven false.

“To try to limit myself to using Billy’s equal sign rather than my “less than” sign would be pretty dumb. In fact, it would probably lead me to engage in the kind of sharpshooter fallacy that he’s been accusing me of since the start of this essay series. If I took the kind of approach Billy suggests here, I could, say, have taken a look at the arrangement of Alma 36 and figured out the probability of producing a chiasm with exactly as many levels as we see. That probability would probably be pretty low.”

If the BoM has 19th origins, what is the *likelihood* it would have the *exactly* as many chiasmi as it does? That number would be low. Astronomically low, even by your standards. But that is only half of the question. The other half is this: IF THE BOM HAS *ANCIENT* ORIGINS, WHAT IS THE LIKELIHOOD IT WOULD HAVE THE *EXACTLY* AS MANY CHIASMI AS IT DOES? That number is going to be astronomically low, too. When you fairly and consistently answer *both* of those questions, you are in a position to create a valid Bayesian model.

In a Bayesian paradigm, the sharpshooter fallacy isn’t characterized by giving the other side a seemingly low probability. It is characterized by giving your own position a probability close to (or equal to) one.

To gain some understanding of the relationship between likelihood and probability and what it has to do with Bayes’ Theorem, here is a primer:

https://alexanderetz.com/2015/04/15/understanding-bayes-a-look-at-the-likelihood/

“And I did.”

You just made me parse through 450 comments worth of material, and for that you shall never be forgiven. At leastwhen I pointed people to those comments they could do a CTRL+F and find my two comments easily enough. You made quite a hobby of corresponding with Bruce and Brant over there.

I may have missed something, but after going through all that I still didn’t see demonstrated evidence of bias. I saw you making further unsubstantiated claims of bias, and I saw you disagree with the Dales on the details of their correspondences, but that’s fine, since clearly I disagreed with them too. I worked pretty hard trying to correct the issues that both you and I saw with their methods, so just patly waving your hand with a pre-fabricated set of critiques feels pretty hollow.

“Those concepts are all from the paradigm of Fisherian statistics.”

It’s true that I could’ve been a purist, and limited myself only to the random-effects models preferred by quantitative Bayesian proficients, but there are some issues with that:

1. Those generally require very large sample sizes, which I almost never had.

2. Almost none of the relevant studies I’m pulling probability estimates from used those methods.

3. Historical Bayesian analysis isn’t the same beast as quantative Bayesian analysis, and isn’t, and can’t, and shouldn’t be required to certain types of estimation methods. (Most historical bayesianists make all their numbers up whole cloth for heaven’s sake).

There’s nothing specific to Bayes’ theorum that requires the use of random effects models–Bayes was long, long dead by the time they were first developed. The idea that the two types of statistics can’t be mixed is essentially a manifestation of mathematical prejudice–each approach can be framed as a derivation of the other, and can in fact be used in combination to fit the needs of the analysis (e.g., mixed effects modeling), and often produce very similar results:

https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Positioning_Bayesian_inference_as_a_particular_application_of_frequentist_inference_and_vice_versa/867707

And there’s zero problem with substituting Bayes probability estimates with ones that characterize a range of outcomes. That’s doubly so in this case, since the idea of describing a range of similarly impactful outcomes is conceptually superior to just describing the single outcome being observed. Unless you can somehow demonstrate that my overall conclusions are dramatically altered by making use of frequentist modeling (in ways that disadvantage the critics), your argument remains pure pedantry (and is likely to be motivatedly so).

“That number is going to be astronomically low, too.”

In a way that leads to similar overall conclusions (aligning with my point above), but that nevertheless produces misleadingly small probability values in each case, in that they reflect the likelihood of finding that specific observed evidence, rather than the likelihood of finding similarly impactful evidence (i.e., as strong or stronger; which, again, is the better way to frame the probability we’re most interested in).

I agree you are perhaps mixing types of statistics. I’m not too worried about it. Even subscribing exclusively to one form of stats or the other won’t make the model accurate per se. Your method of using TTR is nice because it makes calculations feasible. However, it is probably very generous and underestimates the actual odds. So I think this is a conservative guess. Also, if you ask five statisticians you get five answers.

There will always be a “more correct” model. This approach seems very conservative.

I have to say I like what you write about periods. This has been bothering me a little. Recall when Ammon wishes he was an angel and some say he is boasting and he states he “sins in his wish”? Well you can read that as a passing desire or, because it is very chiastic, you might think it was a genuine desire and feeling that he committed to expressing.

I favor the latter but perhaps, as you say, chiasmus were as natural for them as a period is for us.

Also, many of God’s words to Nephi are chiastic. What do we make of that? I’ll let you know if I come up with anything. Glad you integrated Cranney’s data.

Thanks Martin! I’d welcome any “more correct” model that happens to make itself known, but so far there haven’t been many takers!

In terms of God’s words to Nephi being chiastic, I don’t see much issue with that. With Joseph Smith, we have a pretty clear indication that he wasn’t responsible for forming the words of the Book of Mormon, and even some indication that he wasn’t responsible for the wording in the D&C. I’m not sure that’s the case for Nephi. His process for receiving and writing those words seems to have been very different from Joseph’s, and I think it would be reasonable to assume that he’s receiving inspiration and then writing the words in his own (exceptionally chiastic) vernacular.

I am a little disappointed that the undeniable presence of hundreds of parallelisms, including chiasmus, in the Book of Mormon has not generated a lot of comments. I am particularly disappointed that Billy Shears has chosen not to show us how the existence of these parallelisms is not really evidence at all, and that what we should be considering instead is X, or Y or perhaps… Z. I miss you, Billy. 🙂

So I am going to contribute my widow’s mite and hope to elicit some discussion.

I strongly recommend Professor Donald Parry’s wonderful book “Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon”. If you want a powerful experience, try reading the Book of Mormon out loud using Parry’s book, while giving emphasis to the parallelisms in your reading. I have done that twice, all the way through the book, and the experience changed me.

Among the many things that I find remarkable about these parallelisms is how they act to emphasize the doctrine and message of the Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ.

For example, Alma 36 is rightly regarded as a chiastic “gem”. At the turning point of that great chiasm (16 parallel elements on either side of the turning point) we find this phrase “to atone for the sins of the world” (verse 17). The Atonement of Jesus Christ is the fundamental doctrine of Christianity, the linchpin that holds everything else together. And Alma rightly puts the Atonement at the center of his extended, beautiful chiasm.

I believe I am a decent writer. So I thought I would try my hand at writing simple chiasms on doctrinal subjects. I failed completely. Down in flames. I just couldn’t do it.

I think that my early training at the hands of Miss Josephine Hockenbeamer, my 6th and 7th grade English teacher, is “to blame”. Her training has made it really difficult for me to write in a repetitive fashion. Ms. Hockenbeamer (her real name, no smirking, ya’ll) chastised me severely when I repeated myself. I mean severely.

The point is that Ms. Hockenbeamer’s style of training in English composition, i.e., discouraging repetition, is the kind of training that all people writing in English have received over the last few hundred years. We just don’t write that way.

Joseph Smith was 23 years old, and barely literate, when the Book of Mormon was sent to the printer. To think that a person as young as he, or anyone else in his day or our day, was able to write that book using so many and so many truly beautiful Hebrew parallelisms is simply laughable.

So when Kyler estimates that the presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon increases the odds that it is an authentic work by about 14 orders of magnitude, my response is “At least!”.

Thanks for the comment Bruce! I too miss Billy’s insights. I have confirmation that he’s alive and well, though. He seems to think he doesn’t have much unique to contribute that he hasn’t already said in past posts. I’m sure that’s not true, though! His thoughts are always appreciated.

My own experience with writing suggests that the art of chiasmus would be unlikely to come naturally to any modern English speaker. I think back to what it was like trying to write Iambic Pentameter. My brain clued into the rhythm eventually, but it took specific instruction and a lot of practice before that happened. And as a literary technique chiasmus is way more subtle than Iambic Pentameter, and can’t rely on our brain’s natural propensity for rhythmic patterns the same way.

Any thoughts on the use of the TTR as a rough proxy for the frequency of chiasmus? It’s alright to be critical!

Thanks for inviting me to comment on the suitability of TTR for estimating the frequency of parallel word patterns in long texts. I am grateful for your frank invitation to criticize your work…which I took full advantage of in my comments on Episode 14. I believe our mutual respect and (hopefully) growing friendship will survive those comments. 🙂 Please don’t feel any obligation to respond to any or all of my comments…I just wanted to get them out for consideration by whomever is interested.

So, I read Episode 13 three times to try to be sure I understood how you were using TTR. I agree that TTR is a reasonable way to quantitatively estimate the richness of the vocabulary of a text, the reciprocal of which should provide a reasonable estimate of the degree of repetition which in turn is the primary characteristic of chiasmus and other poetic parallelisms. In short, I think your analysis is well-founded and the conclusions supported by the analysis.

At first glance, there is one apparent exception to the Inverted TTR trend for scriptural versus non-scriptural texts, namely the book of Isaiah. Isaiah appears to be much closer to the logarithmic fit line for modern works versus that for scriptural works. How do we explain that? I think it is pretty straightforward and tends to support your overall conclusions in this Episod.

There is in fact a great deal of chiasmus and parallelism in Isaiah (see reference below). While I am not prepared to go through Isaiah versus Leviticus and determine whether they have more or less parallelism per 1000 words, I would simply note that “great are the words of Isaiah”.

To me, Isaiah has a richer vocabulary and is certainly a greater poet than any of the other Old Testament writers. Poets tend to say the same thing in different words, more so than us ordinary writers. Isaiah does repeat himself, he just tends to use different words to do so. Thus Isaiah’s Inverted TTR would trend down because he is a great poet, therefore he is possessed of a greater vocabulary.

Hope this is useful.

Bruce

http://byustudies.byu.edu/article/chiasmus-in-the-text-of-isaiah-mt-isaiah-versus-the-great-isaiah-scroll/

Thanks for the comments Bruce. I agree that the ability of the TTR to distinguish between Leviticus and Isaiah is a good sign for its ability to capture differences in repetitive poetic forms.

“I believe our mutual respect and (hopefully) growing friendship will survive those comments.”

Most assuredly!

Hi Bruce,

I’ve been losing interest in responding to these posts, and I suppose I owe it to anybody who has been following my comments to explain why.

In your paper about The Mayan, you had some huge biases: your method for selecting evidence to be considered was structurally biased, and your judgment in applying the specific-detailed-unusual heuristic for estimating likelihood ratios was biased. Also, the assumption that the various points are statistically independent is dubious. That said, I had no problem with the underlying Bayesian model you used.

In the current analysis, not only are there problems with biases in the assumptions and with statistical independence, the underlying math doesn’t correctly using Bayes’ Theorem. Let me explain.

This paper uses the following formula for Bayes’ Theorem:

PostProb = [PH * CH] / [(PH * CH) + (PA * CA)]

Using a mathematically valid interpretation of the formula:

CH = P(X = E|A)

CA = P(X = E|M)

The first equation represents the likelihood the random variable (X) is equal to the actual evidence we see (E), assuming the book is ancient (A).

The second equation represents the likelihood that the random variable (X) is equal to the actual evidence we see (E), assuming the book is modern (M).

That is the mathematically correct interpretation of this formula. Rather than doing that, these episodes do something like this:

CH = P(X <= E1|A)

CA = P(X <= E2|M)

There are two changes here. First, the equal sign in Bayes formula is changed to the less-than-or-equal-to sign. (This is driven by the episodes’ repeated error of using Fisherian P-values for CH and CA. P-values are from a completely different statistical paradigm and the main motivation of using Bayesian inference is to get away from them). A mathematically coherent interpretation of Bayes’ theorem is that we’re looking at the *likelihood* of seeing the specific evidence we see under each scenario. The p-value is something different and if you plug a p-value into the formula rather than the likelihood of seeing the evidence, the result is mathematical gibberish.

The second change is that rather than evaluating the same body of evidence under both hypotheses, the episodes typically select one body of evidence to use for the ancient hypothesis (E2), and another to use for the modern hypothesis (E1).

These are fundamental problems—it’s like somebody saying that the formula Force = Mass * Acceleration is inconvenient, so they are going to redefine it as Force = Mass + Acceleration. Because the structure of this analysis is so fundamentally flawed, I just can’t bring myself to continue taking it seriously.

At first I tried to overlook the flaws in the mathematical model itself and focus on the issues. But the errors there are fatal and are getting repetitive. The basic approach is as follows:

1- Find a mathematically quantifiable characteristic of a book that is in some way vaguely related to BoM apologetic (e.g. TTR is assumed to be related to chiasmus)

2- Find a handful of 19th century books.

3- Calculate the statistic for the 19th century books and fit it to a normal distribution.

4- Do a Chi-squared test or a p-test or whatever, and calculate the probability that the BoM fits into that distribution

5- Plug that Fisherian statistic into the model for CH

6- Plug the number 1 or a number very close to 1 in for CA

In addition to Bayes’ formula being misused with a p-value rather than a likelihood, this has the following problems:

1- As Kyler’s own data typically shows, the assertion that 19th century books are normally distributed is false

2- Critics don’t contend the BoM is statistically homogenous with other 19th century books–it can be different than other modern books and still be modern

3- The BoM having characteristics that are different than other 19th century books has no bearing on whether or not its ancient

To salvage this type of analysis, every time Kyler compares the BoM to 19th century books, he should also compare it to ancient Mayan books (e.g. The Dresden Codex, the Madrid Codex, the Paris Codex, and of course the Popol Vuh), or to real-world ancient texts that have been written on metal plates (e.g. the Copper Scroll in the Dead Sea Scrolls). If he was able to demonstrate that the BoM fits with authentic ancient texts more than with the books J.S. had available (including the KJV version of the Bible), I would be impressed.

But of course he doesn’t do this. He makes special pleadings about why the BoM should be expected to be different than real-world non-biblical ancient books. That is my point—just as an authentic BoM is different than actual non-biblical books, a modern BoM is different than other modern books.

In general, books are the result of human creativity. There really isn’t an underlying rule that any of their characteristics must follow a statistical distribution.

And that's the biggest flaw here. Some things…

Thanks for taking the time to comment Billy, and I think these are thoughts worthy of a response. If this is the last we see of your thoughts here that will sadden me, since your comments have always given me opportunities to think through and express things more clearly.

“In your paper about The Mayan, you had some huge biases”

You might as well have spelled it “yuuuuge”.

“Your method for selecting evidence to be considered was structurally biased, and your judgment in applying the specific-detailed-unusual heuristic for estimating likelihood ratios was biased.”

It would be helpful for you to substantiate these claims, and I think you would’ve if you could. Of course the process for selecting and evaluating evidence is unavoidably biased (thus the a fortiori measures), but I’m not sure what concrete mechanisms you have in mind for producing that bias. In terms of identifying pieces of evidence, I think the Dales did what they could to limit themselves to items in Coe’s actual textbook (and, vise versa, to what Coe himself has identified as anachronisms in various forums), and I’ve done what I could to pare things down even further (lopsidedly, on behalf of the critics). And the designations of specific, detailed, and unusual are messy, of course, but I think they’re applied with a reasonable degree of consistency across both sides. If you have other numbers you’d stick in there I’d be willing to listen to your proposals, but somehow I suspect that bias would start kicking in the other way.

“The p-value is something different”

I think it’s worth talking about what that “something different” actually is, which you seem to want to avoid doing. When you do, the pedantic (and problematic) nature of your claims here become pretty clear.

And I’ll note at this point that I think you know these are problematic and pedantic, and that this represents a bit of a last ditch effort to discredit what I’m doing here by deploying an argument that you hope people won’t actually understand.

What the equal sign is doing is identifying the probability of a given event–in this case, the probability of observing a particular piece of evidence. As an analogy, you could ask what the probability is that someone could have a child that’s 6’7″. In doing so, you could examine how height is distributed in the general population, and then look at the number of children born where were exactly 6’7″. That number would probably be pretty low.

But in the case of Book of Mormon evidence, we don’t really care about the probability of observing the exact evidence that we ended up with–the probability of observing the EXACT amount of chiasmus that we have in the BofM is pretty small–we care more about observing evidence similar to or at a similar strength to what the BofM has. In that case, when we talk about observing a piece of evidence, we’re not talking about a single outcome, but a range of outcomes–the probability of observing evidence as strong or stronger than can be observed within the BofM.

It would be akin to asking what the probability is that someone could have a child 6’7″ OR HIGHER. When asking statistical questions in the social sciences and elsewhere, this is exactly the kind of question that gets asked–the probability of observing differences as large or larger between groups. Chi-squares and t-tests and ANOVAs are pretty good at producing those sorts of probability estimates, and they’re important for hypothesis testing. It’s an acknowledgement that the result might have turned out differently on the basis of chance alone, and that chance could not only have produced a specific F or chi-square, but also an F or chi-square that was even larger than what this specific test produced. In short, it covers one’s statistical bases by allowing for a range of similar outcomes rather than reporting the probability of obtaining a specific statistics.

To try to limit myself to using Billy’s equal sign rather than my “less than” sign would be pretty dumb. In fact, it would probably lead me to engage in the kind of sharpshooter fallacy that he’s been accusing me of since the start of this essay series. If I took the kind of approach Billy suggests here, I could, say, have taken a look at the arrangement of Alma 36 and figured out the probability of producing a chiasm with exactly as many levels as we see. That probability would probably be pretty low. It would probably be more fair to the critics though, to estimate the probability of seeing a chiasm with that many levels or higher, as faithful scholars would probably been crowing just as loudly had that been the case. The test would then spit out a higher probability value, advantaging both the critics and common sense.

To be continued…

Part 2:

“The second change is that rather than evaluating the same body of evidence under both hypotheses, the episodes typically select one body of evidence to use for the ancient hypothesis (E2), and another to use for the modern hypothesis (E1).”

We’ve been over this before, and it reflects the reality that different pieces of evidence are unexpected under different hypotheses, and that sometimes different comparisons make better sense under different hypotheses. If you preferred, I could go back through each of the essays an insert p = 1 for the evidence not specifically treated under each hypothesis (and I do that explicitly in some cases), but that would probably get a little redundant. If you think that p shouldn’t equal 1 in these cases, then that’s worth talking about, but the practice of failing to specifically report every single value in a blog series like this one is generally a matter of aesthetics rather than substance.

“he should also compare it to ancient Mayan books (e.g. The Dresden Codex, the Madrid Codex, the Paris Codex, and of course the Popol Vuh), or to real-world ancient texts that have been written on metal plates (e.g. the Copper Scroll in the Dead Sea Scrolls)”

The issue of proper comparisons is a valid one, and we’ve generally discussed those when they’ve come up. In those cases, what I’ve been doing isn’t so much special pleading as it is thinking critically about what sort of comparison makes the most sense in each case. Universally and blindly conducting comparisons with Mayan or other ancient texts would be obtuse, full stop. It sounds like you’d insist that, alongside something like chiasmus or page counts, where that comparison might, if you squint hard enough, make a little bit of sense (though biblical comparisons are obviously more relevant given what the book claims for itself), I should analyze levels of Early Modern English in Mayan or non-biblical texts. In what universe would that make sense? Apparently Billy’s, and he can have that corner of the multiverse to himself as far as I’m concerned.

“In general, books are the result of human creativity.”

This, to me, is similar to arguments made on the faithful side that God can do anything he wants. In fact, it’s worse, since at least it makes logical sense that an omnipotent God could produce outcomes that don’t appear to follow natural law. Hiding behind the unlimited powers of human creativity to explain the features of the BofM is at best unwise, because we know full well that those powers aren’t unlimited. Books, as with most things human, often do tend to follow statistical distributions, and we should only have so much tolerance for a book that defies those distributions in as many strange and varied ways as the Book of Mormon. This is particularly when the mechanisms that critics propose for Joseph or others producing them are either vague, implausible or non-existent.

Thanks Billy! Sounds like you might have some more material that didn’t make it into your first comment, and I’ll likely respond if and when that shows up.

Hi Billy,

It has become pretty hard for me to take you or your criticisms seriously. I did not arrive at this point quickly.

If you will recall, you and I exchanged a lot of comments a couple of years ago following the publication of our Interpreter article “Joseph Smith: the World’s Greatest Guesser”. Kyler used this article as a starting point for episode 14. Our article claims that there are 131 separate facts cited by Dr. Michael Coe in the Ninth Edition of his book The Maya that correspond to statements of fact in the Book of Mormon.

Since Dr. Coe has said that “99% of the details in the Book of Mormon are false” we have a problem. Either Dr. Coe’s knowledge of the Book of Mormon is sadly lacking, or I am grossly misreading The Maya, and those 131 correspondences do not actually exist.

In November 2018, I contacted Dr. Coe and asked if he would be willing to re-examine his opinion of the Book of Mormon based on the 131 correspondences I had identified. I asked him to point out where I was mistaken. He declined. I then politely asked him how many times he had read the Book of Mormon. With equal politeness, he replied “Once” (in about 1972).

I have read the Book of Mormon several hundred times, and I have read various editions of Coe’s book The Maya about 30 times. So I think I am in a pretty good position to identify correspondences between the two books. Dr. Coe’s lack of effort to read and understand the Book of Mormon is not scholarship, it is prejudice. Dr. Coe did not know what he was talking about when he dismissed the Book of Mormon.

So much for Dr. Coe: now to Billy Shears.

During our exchange of comments on the Interpreter paper, I offered to buy a copy of The Maya for you and anyone else who would like to read it and check to see if I was making up all the correspondences. You declined and so did every other critic of our paper.

The existence (or not) of those 131 correspondences is a primary issue, much more so than the Bayesian analysis. There is no point in applying Bayesian analysis, or any other tool, to correspondences that do not exist, correspondences that you and others refuse to check and either confirm or refute. In our exchange of comments two years ago, rather than check the correspondences, rather than deal with the evidence itself, your approach was always to change the subject.