An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 18:

“Be Strong and of a Good Courage”

(Joshua 1-6; 23-24) (JBOTL18A)

Figure 1. James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902): The Songs of Joy, ca. 1896-1902

Question: Israel was commanded to “utterly destroy”[2] the Canaanites and the book of Joshua later claimed that they had done so.[3] Why do archaeological findings[4] and other references in the Bible[5] make it seem that this was not actually done? What does it mean to “utterly destroy”? And why would God command such a thing in the first place?

Summary: There is no simple answer to these questions. As confidence in the likely timeframe for the Exodus and the rise of early Israel has increased, it has easier for archaeologists to pinpoint the conditions in Canaan when Joshua and his people entered the land. Surprisingly, there is little evidence for the picture of widespread warfare and displacement of Canaanite religion and culture that the book of Joshua seems to portray. After summarizing the archaeological evidence, I will argue that we can sometimes be misled by the assumptions we make when we encounter difficult-to-understand scriptural passages. Although the scriptures are trustworthy, coming to understand them is a lifelong effort. To understand the book of Joshua, we need to consider that its purpose is something more than simply laying out “exactly what happened” (in the modern sense) when Israel entered Canaan. Part of the problem in understanding Joshua may be in that the words “utterly destroy” do not accurately convey the meaning of the Hebrew term ḥerem. The story of Joshua should be interpreted in light of the larger, divine scheme of things outlined throughout the rest of scripture. It is a story from which everyone can continue to learn.

The Know

Figure 2. James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902): Moses (detail), ca. 1896-1902

As the archaeological record has become more clear and definite, the story of the conquest of Canaan found in the book of Joshua has emerged as a point of controversy. John Walton summarizes the question that has been raised by many people, especially in light of horrendous acts of “ethnic cleansing” that have occurred in modern times:[6]

“Is God some kind of moral monster that he would commit or condone genocide?” This has indeed become a major thorn in the flesh for many Christians … and not only because the skeptics of the world have positioned it as the major indictment against the Bible, the God of the Bible, and Christians who take the Bible seriously. It has also become a catalyst for Christians to begin to doubt the Bible, doubt their God, and doubt their faith.

In this article, I will attempt some tentative answers to questions such as the one above that may arise in reading the book of Joshua. As a foundation for understanding the archaeological record as it pertains to the biblical account of Israel’s entry into Canaan, I will review selected conclusions about the historical context of the Exodus that were argued in previous articles in this series. Then I will outline the principal reasons why Joshua’s account has become a problem for some scholars.

I will draw on the work of Bible scholar John Walton to draw some tentative conclusions as to what a “literal” reading of the book of Joshua might look like, including a perspective on the significance of the command to “utterly destroy.” I will also describe some ways in which the picture of the times provided by the book of Judges seems to match the historical record.

Finally, I will draw some broader lessons about our day.

Review of Previous Conclusions About the Historical Context of the Exodus

Previous articles in this series have addressed the historical context of the sojourn of the Israelites in Egypt and their eventual journey to the promised land of Canaan. Arguments were made for the following conclusions:

- Knowledge of Egyptian traditions in the biblical account of the plagues. The story of the plagues in Exodus demonstrates much more than a passing acquaintance with Egyptian traditions, religion, and magical practices.[7] Rather, it seems to have originated with individuals who had intimate knowledge of Egyptian lore. As a whole, the biblical account brilliantly conveys how Pharaoh and his gods were vanquished by Jehovah. An examination of its details makes it clear how the particular choices made for the demonstrations of God’s power would have hit home in power and precision with Israel’s opponents in Egypt.[8]

- Size and timeline of the wilderness crossing. Archaeological evidence for a group of millions of Israelites crossing the Sinai desert is lacking and unlikely to be forthcoming.[9] Some of this is due to the near impossibility of resurrecting evidence from the region’s marshes and sands,[10] but the large numbers given in the Bible are implausible for other reasons as well.[11] Although it is certain that many Semitic people came and went from Egypt in the centuries before the Exodus, current evidence seems to indicate that Moses’ group must have been relatively small.[12] As far as the timing of the Exodus goes, it seems reasonable to accept Gary A. Rendsburg’s conclusion that “whatever history may underlie the Bible’s narrative should be placed in [the] general timeframe” of the nineteenth and twentieth Egyptian dynasties (1250-1175 BCE).[13] In agreement with most biblical scholars who accept the Exodus as historical, this would place the height of the oppression of the Israelites in Egypt during the reigns of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) and his successors, notably including Merneptah (1213-1203 BCE). However, Rendsburg would place the Exodus itself later, in the reign of Ramesses III (ca. 1175 BCE). This was a period of distraction and declining influence for Egypt. Considering this general timeframe together with the evidence provided by the Merneptah stele (1209 BCE), it seems that there must have been a loosely organized people known as “Israel” already living in Canaan before the group from Egypt arrived.[14] This indigenous “Israel” either would have returned to Canaan from Egypt earlier than the group led by Moses or would have never gone to Egypt in the first place.

- Indirect Egyptian evidence for the timing of the Exodus based on structural parallels with accounts of the battle of Kadesh. Although a significant presence of Semitic peoples in Egypt over a period of centuries is well-documented, no direct evidence for the Exodus itself has been found in Egyptian sources. This is not surprising because the Egyptians, like other ancient (and modern!) peoples, were loath to advertise any defeat in truthful candor. However, Joshua Berman has brought to light indirect evidence from Egypt that bears on the Israelites’ escape from oppression.[15] He has argued that the oldest description of Israel’s final departure in the book of Exodus intentionally imitated the structure and vocabulary of Egyptian propaganda that trumpeted a claimed victory at the battle of Kadesh. According to this conception of things, Exodus would have appropriated elements of the structure and vocabulary of this story to mock the pharaoh’s failure to stop the flight of Moses and his followers. Berman further argues that the biblical “Sea Account”[16] of the Exodus must have been authored by someone who lived not long after the battle and was well-acquainted with the Egyptian inscriptions that reported it. This timing is consistent with the general timeframe of the Exodus accepted by many biblical scholars and more specifically delineated by Rendsburg above.

- Indirect evidence from Egypt for the timing of the Exodus based on parallels to the Camp of Israel, the Tabernacle, and its Ark. Adding to the evidence for a stock of detailed knowledge about Egyptian history and tradition woven into the book of Exodus, scholars such as Michael M. Homan[17] and Myung Soo Suh,[18] have argued convincingly that the layout of the camp and war tent of pharaoh at the battle of Kadesh closely resembled the camp and tabernacle of Israel. In addition, Scott B. Noegel,[19] among others, has highlighted evidence of Egyptian parallels to the Ark of the Covenant. Similar comparisons, of course, also could be made with permanent Egyptian and Israelite temple structures whose original design was inspired by those “seeking earnestly to imitate that order established by the fathers in the first generations,”[20] as LDS scholars such as Hugh Nibley[21] and John Gee[22] have argued. If Berman’s arguments hold true that the Exodus account exploited contemporary Israelite knowledge about the battle of Kadesh, it would not be unreasonable to suppose that planning for the construction of the camp of Israel, the Tabernacle, and its furnishings was not only revealed directly to Moses, but, in addition, may have been informed to a greater or lesser degree by Egyptian precedents in the war camp of pharaoh during that same battle.

- Evidence from modern scripture. Because Latter-day Saints accept the Bible only insofar as it is “translated correctly,”[23] the additional witnesses of modern scripture and the teachings of Joseph Smith and his successors provide valuable confirmation of the historical reality of the prophet Moses (who appeared personally to Joseph Smith in the Kirtland Temple[24]), the general outlines of the Exodus (referenced in many places throughout modern scripture) — and especially of the Lord’s efforts to sanctify Israel at Sinai (see especially JST Exodus 34:1-2 and D&C 84:6, 23-25, 31-34).

With these conclusions about the historical context of the Exodus in mind, we are ready to examine the story of Israel’s entry into Canaan as portrayed in the book of Joshua. First, I will summarize two of the reasons that Joshua’s account of the conquest of Canaan has become problematic for scholars. Then I will argue that a reexamination of common assumptions relating to the books of Joshua and Judges can provide helpful perspectives on these problems.

Why Has Joshua’s Account of the Conquest of Canaan Become a Problem for Some Scholars?

A brief answer to the question posed above can be put simply:

- Evidence of significant population growth unaccompanied by violent destruction. On the face of it, this finding seems to contradict Joshua’s account of a wide-scale military conquest of Canaan.

- Evidence of religious continuity in Canaan. Archaeologists have found no evidence of significant changes in religious practices in Canaan spanning the plausible timeframe of Joshua’s entry into the promised land. This and other evidence seems to contradict the idea of a large-scale in-migration of an Exodus group who were successful suppressing local traditions and in establishing the exclusive worship of Jehovah throughout the land.[25]

Below we briefly summarize the arguments for these two findings.

Evidence of significant population growth unaccompanied by violent destruction. During the period presumed to have followed the Exodus, there was a significant “increase in population in the rural and hinterland areas, particularly in the central hill country west of the Jordan, where the frontier was open.”[26] However, “overwhelming archaeological evidence” disproves the possibility of “large-scale warfare on the thirteenth- and twelfth-century horizon.”[27]

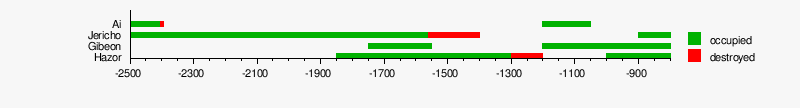

Figure 3. Summary of archaeological evidence for the occupation and destruction of four of the cities mentioned in Joshua[28]

The figure above summarizes archaeological evidence for the occupation of four of the cities mentioned in Joshua. Of the three of them were specifically said to have been destroyed by fire (Jericho,[29] Ai,[30] and Hazor[31]), only Hazor appears to have been occupied at the time. Gibeon, the fourth city shown here, with whom Joshua was said to have “made peace,”[32] was populated about 1200 BCE, a few decades prior to the most plausible timeframe for Israel’s entry into Canaan.

The eminent archaeologist William G. Dever summarizes the current consensus of scholars:[33]

Of the thirty-four sites in Joshua, only Hazor, Zephath, Gaza, and perhaps Bethel could possibly have been overcome or even threatened by incoming Israelite peoples, much less by local lowland refugees or nomads. There may have been some regional conflicts between the local population and the new settlers who are by now well documented. … The book of Joshua gets it entirely right only once; it omits Shechem in Joshua 12, which turns out to be correct, since the site was not destroyed.

Later in the article, I will offer some perspectives on the discrepancy between archaeological data and the book of Joshua.

Figure 4. James Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836-1902) : The Idols Are Brought Out (Judges 18:18), ca. 1896-1902

Evidence of religious continuity in Canaan. Dever summarized the evidence of religious continuity before and after the plausible timeframe of the Exodus as follows: “We now know that Israelite folk or family religion (and even organized religion) were characterized by many of the same older Canaanite features from start to finish.”[34]

Though there is evidence for discontinuity in other respects before and after the plausible timeframe of the Exodus (e.g., population increase in the hill country, innovations in housing, the economy, social structure, and political organization[35]), Dever and most other mainstream archaeologists[36] have concluded that the great majority, at least, of what he calls the “proto-Israelites” who began to settle the hill country in great numbers were already native to Canaan and fully immersed in the local culture:[37]

The [new settlers of the hill country] are neither invaders bent on conquest nor predominantly land-hungry pastoral nomads. They are mostly indigenous peoples who are displaced, both geographically and ideologically. They find a redoubt [i.e., safe refuge] in areas previously underpopulated, well suited to an agrarian economy and lifestyle. In time, these people will evolve into the full-fledged states of Israel and Judah known from the Hebrew Bible.

While the picture currently provided by archaeologists of religious continuity in Canaan before and after the Exodus differs from earlier reconstructions of the history of Israel, it should not be too surprising when we consider the likelihood that the Israelite group arriving from Egypt was relatively small, perhaps no bigger than the loosely organized people known in the Mereneptah stele as “Israel” who were already living in Canaan when Joshua arrived.

Although these indigenous Israelites were sufficiently distinctive to have been identified by name as a separate people in 1209 BCE, it seems they had mixed with the local populations to such an extent that today they are more or less indistinguishable from the Canaanites in their material remains. In short, just as Moses found it easier to take the Israelites out of Egypt than to take “Egypt” out of children of Israel, so it seems that it must have been easier to bring a new group of Israelites to Canaan than to remove “Canaan” from the Israelites who had mixed with their neighbors for generations. It would be a long time before a critical mass of the “mixed multitude”[38] became sufficiently cohesive and distinctive — culturally, politically, and religiously — that it could come together as a united kingdom of Israel under David.

Are There Good Reasons to “Doubt Our Doubts”?

Figure 5. Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf

Can the Bible be trusted? Readers responding the archaeological evidence might be tempted to take an extreme position. For example, they might decide that the biblical accounts of Israel’s entry into Canaan have no value as history and pay attention only to the archaeological findings. Or they might decide instead that the archaeological findings are biased and worthless, and that they should pay attention only to what the Bible says. However, I think that taking either of these extreme approaches would be a mistake.[39] In the appendix to this article, “Why Is It Important to Counterbalance the Study of Scripture in Its Scientific and Historical Context With Traditional Forms of Scripture Reading?,” I give some reasons for my conclusion.

At this juncture, however, I would like to underscore a conviction I have come to that — to a degree much greater than I would have thought some years ago — I can generally trust what I read in the Bible and, with an even more firm assurance, what I read in modern scripture. In that light, I have come to appreciate the following advice about reading scripture by Faulconer:[40]

Assume that the scriptures mean exactly what they say and, more important, assume that we do not already know what they say. If we assume that we already know what the scriptures say, then they cannot continue to teach us. If we assume that they mean something other than what they say, then we run the risk of substituting our own thoughts for what we read rather than learning what they have to teach us. … [A]ssume that each aspect of whatever passage we are looking at is significant and ask about that significance. To assume that some things are significant and others are not is to assume, from the beginning, that we already know what scripture means. Some things may turn out to be irrelevant, but we cannot know that until we are done.

Similarly, Bible scholar N. T. Wright comments that if you read in this way:[41]

… the Bible will not let you down. You will be paying attention to it; you won’t be sitting in judgment over it. But you won’t come with a preconceived notion of what this or that passage has to mean if it is to be true. You will discover that God is speaking new truth through it. I take it as a method in my biblical studies that if I turn a corner and find myself saying, “Well, in that case, that verse is wrong” that I must have turned a wrong corner somewhere. But that does not mean that I impose what I think is right on to that bit of the Bible. It means, instead, that I am forced to live with that text uncomfortably, sometimes literally for years (this is sober autobiography), until suddenly I come round a different corner and that verse makes a lot of sense; sense that I wouldn’t have got if I had insisted on imposing my initial view on it from day one.

Generalizing this kind of approach, Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf’s famously gave this inspired counsel: “Doubt your doubts before you doubt your faith.”[42]

Can we be misled by our assumptions? Although I have come to trust scripture, I have also begun to learn how little I really understand it. Indeed, sometimes what I think I already know has gotten in the way of that understanding. Experience has taught me that if I blithely assume that my current way of looking at a particular passage is the only way to look at it I am in danger of making what has come to be known as “Frege’s mistake”:[43]

When [Gottlob] Frege heard about [Bertrand] Russell’s discovery of paradoxes in his own and Frege’s theories, the latter cried out: “Die Arithtnetik ist ins Schwanken geraten!” (Roughly, “Arithmetic has been set spinning!”). In fact, it was not arithmetic, but Frege’s theory of arithmetic, that was set spinning.

How can I avoid making Frege’s mistake with regard to the book of Joshua? To do so, I need to take another look at the “theory” that unconsciously undergirds the way I understand the purpose of the book. In that light, here are two assumptions that I think could be reexamined:

- That the purpose of the book of Joshua is simply to lay out “exactly what happened” (in the modern sense) when Israel entered Canaan;

- That Joshua and Judges tell the same story.

Assumption 1: That the purpose of the book of Joshua is simply to lay out “exactly what happened” (in the modern sense) when Israel entered Canaan. The Prophet Joseph Smith held the view that scripture should be “understood precisely as it reads.”[44] In saying this, however, it must be realized that what ancient peoples understood to be a literal interpretation of scripture is not the same as what most people think of today.

Figure 6. Pouring from a cup

Whereas the modern tendency is to apply the term “literal” to accounts that are accurate in the journalistic dimensions of “who, what, when, and where,” premoderns were more apt to understand “literal” in the sense of “what the letters, i.e., the words say”[45] — in other words, what they mean in relation to the larger, divine scheme of things. To clarify the distinction between giving an accurate description of “exactly what happened” in the modern sense and expressing the truth meaningfully in the premodern sense, BYU professor James E. Faluconer gives the following example:[46]

“Person A raised his left hand, turning it clockwise so that .03 milliliters of a liquid poured from a vial in that hand into a receptacle situated midway between A and B” does not mean the same as “Henry poured poison in to Richard’s cup.”[47]

Same video clip, different narrator.

To those who wrote the Bible, it was not usually enough to describe events in photojournalistic fidelity. Rather, an inspired author would most often want to write history in a way that acknowledged the hand of God within every important occurrence.[48] To the ancients, important events in history were part of “one eternal round.”[49] They took pains to help the reader detect that current happenings were consistent with divine patterns seen repeatedly within scriptural “types” at other times in history — past and future. A simple description of the bare “facts” of the situation, as we are culturally conditioned to prefer today, would not do for our forebears.[50] In the view of ancient authors, what readers needed most was not a simple chronological recital of events, but rather help in recognizing the backward and forward reverberations of a given story elsewhere in scripture. This entailed shaping the details of the story so that the fit to relevant patterns would be obvious to a well-informed and attentive audience.[51]

The table above[53] gives an example of this biblical practice. It shows how the themes of chaos/flood, creation/exodus, and covenant are repeated throughout the Old and New Testaments.[54]

The historical books of the Bible differ, of course, in the extent to which they apply a typological template to the events they describe. For example, as we will see below, the redactor of Judges seems to have a different overall scheme for the book than strong typological agenda that pervades the first six books of the Bible. Because of that agenda, we will be misled if we read the book of Joshua as if it were simply a history of “exactly what happened” when the Israelites entered the promised land. Nor should it be regarded even more dismissively as merely “a legend celebrating the supposed exploits of a local folk hero.”[55] Rather, the “literal” understanding we seek of the book of Joshua will be found in an unraveling of the interconnections among what might be called the “tangled plots”[56] of the first six books of the Bible and in an interpretive approach that attempts to comprehend how the individual story plots fit within the scheme of larger plots throughout the Hexateuch (the five books of Moses plus Joshua) — and sometimes further afield.[57]

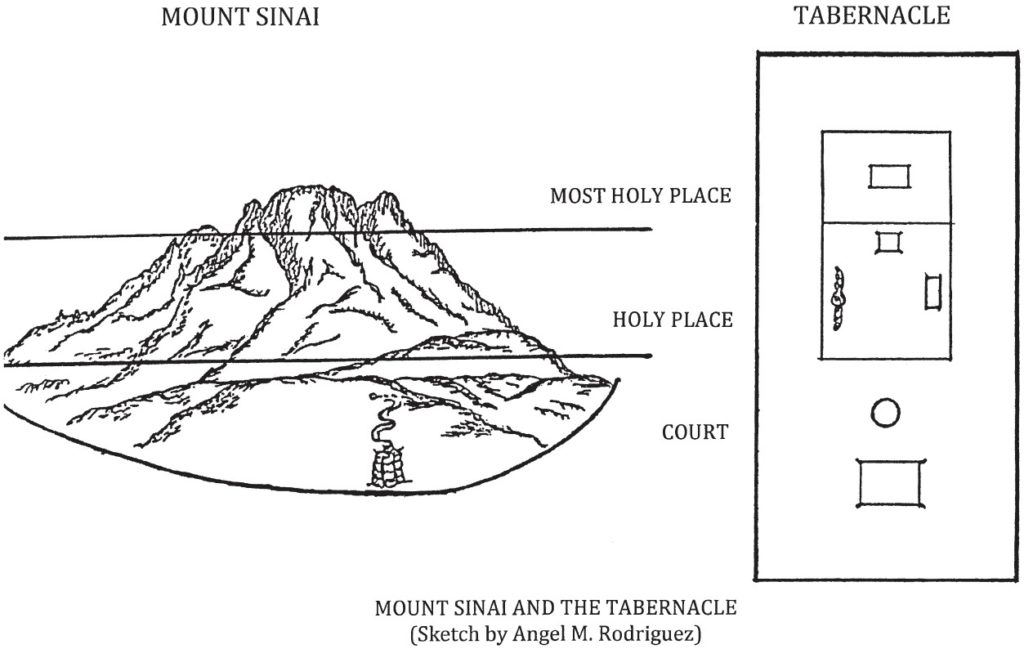

Figure 8. Correspondence Between Mount Sinai and the Layout of the Tabernacle[58]

What is the most obvious way that Joshua is interconnected with the rest of the Hexateuch? Without a doubt it is in the shared theme of God’s quest to establish a holy place and a prepared people to dwell in His presence.[59] In a previous article in this series, we argued that this theme is central to the message of Israel’s sojourn at Sinai and its most prominent previous parallel in the story of Creation and the Garden of Eden as models for the temple. The figure above was used to illustrate the correspondence between Mount Sinai and the Israelite Tabernacle.

Now imagine a similar correspondence between the Tabernacle and the whole of the promised land. Described by Isaiah as “the mountain of the Lord’s house,”[60] the Jerusalem temple will be identified — like Eden — both as the equivalent of the top of Mount Sinai and also as a symbol of the sacred center.[61] As a famous passage in the Midrash Tanhuma states:[62]

Just as a navel is set in the middle of a person, so the land of Israel is the navel of the world.[63] … The land of Israel sits at the center of the world; Jerusalem is in the center of the land of Israel; the sanctuary is in the center of Jerusalem; the Temple building is in the center of the sanctuary; the ark is in the center of the Temple building; and the foundation stone, out of which the world was founded, is before the Temple building.

In such traditions, the sacred center of the temple (or, analogously, the top of the sacred mountain) is typically depicted as the most holy place, and the degree of holiness decreases in proportion to the distance from the center (or the top).[64] In the view of the promised land as the dwelling place of the Lord, the Jordan River — the eastern boundary of Canaan — corresponds to the outermost limit of sacred space.[65]

The bold hope of the returning Israelites portrayed in the book of Joshua is that this time they were not going to expelled from “Eden” because of transgression. The covenant that God had made with Abraham that his posterity would inherit the land of promise for all time finally seemed at the point of fulfillment.[66] The earnest yearning of the book of Joshua is that Israel would be determined this time not to stand “afar off”[67] from the presence of the Lord as they had done at Sinai, but rather that they would build a temple in the heart of the land and ultimately prepare to meet their God face to face — thenceforth “to dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”[68]

Although in the space of this article I cannot dwell at length on temple themes in the book of Joshua,[69] I would like to draw on the writings of John Walton to illustrate the significance of the conquest of the Canaanites in temple terms. Before doing that, it is important to understand the importance of land in relation to the covenant that God established with Israel:[70]

In the ancient world, it was common for elites (especially kings) to grant land possession to faithful or important associates or vassals. But the land, of course, remained the property of the overlord. These grants were often broadly conditional but also of an enduring nature (that is, not for a specified term but in perpetuity, a lasting possession). … The word ʿôlām [eternal, everlasting] does not communicate that the possession of the land can never be withdrawn, as evidenced by the very fact that it was withdrawn [during the Israelite] exile. So why did God offer land as part of the covenant, and what function does it have in the covenant? From the breadth of the biblical evidence, I suggest that the land is given not so that Israel will have a place to live but to serve Yahweh’s purposes as he establishes his residence among his people. It does give them a place to live, but the point is that it is where they will live in the presence of God. Yahweh is going to dwell in their midst in geographical space made sacred by His presence. The land has to do with His intentions for His presence; He desires to establish a place where He lives among His people, not just to give His people a place to live.[71] …

At the other end of the Old Testament, when the prophets speak of the future restoration of Israel and the return from exile, the return to the land is almost always associated with the restored presence of God in their midst.[72]

In trying to understand the reason God would command Israel to “smite” the peoples then living in Canaan, to “utterly destroy them,” to “make no covenant with them, nor shew mercy unto them,”[73] it should be noted that we have relatively little to go on outside the Old Testament itself. Joshua is not mentioned by name once in modern scripture, and the Prophet Joseph Smith mentions his name only two times in passing.[74] However, there is an extensive condemnation of the wickedness of the Canaanites in 1 Nephi 17:32-40.[75] The gist of this passage that “this people [i.e., the Canaanites] had rejected every word of God, and they were ripe in iniquity; and the fulness of the wrath of God was upon them; and the Lord did curse the land against them, and bless it unto our fathers.”[76]

Though some scholars have argued that the Canaanites were not guilty of any sin that might warrant their destruction,[77] the strength of Nephi’s indictment of the Canaanites is even more understandable if we assume that some of their number included indigenous Israelites whose ancestors had once been part of a covenant people, as had been the presumably Abrahamic peoples east of Jordan who had been treated as adversaries by Israel. Moreover, the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah provide a precedent for non-covenant people who were judged ripe for destruction by the Lord.[78] Of the Sodomites, President John Taylor, then an apostle, wrote:[79]

It was better [in the eyes of the Lord] to destroy a few individuals than to entail misery on many. And hence the inhabitants of the old world, and of the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed, because it was better for them to die, and thus be deprived of their agency, which they abused, than entail so much misery on their posterity, and bring ruin upon millions of unborn persons.

Important to our discussion of the fate of the Canaanites is the meaning of the word ḥerem:[80]

The common English translations of the Hebrew word ḥerem (ASV “utterly destroy”; NIV “destroy totally”; CEB “place under the ban”; NET “utterly annihilate”; ESV “devote to destruction”) are misleading because they imply that the word specifies something that happens to the object (that is, it is destroyed). Alternatively, we suggest that the word actually refers to the removal of something from human use. The emphasis is not on the object but on everyone around the object; “no one shall make use of this.” When ḥerem objects are destroyed, the purpose of the destruction is to make sure that nobody can use it, but not all ḥerem objects are destroyed. Most notably, Joshua 11:12-13 reports that all of the northern cities were ḥerem, yet Joshua destroys only one of them (Hazor). Likewise, a field that is ḥerem is not destroyed but becomes the property of the priests.[81] Destruction, when it occurs, is a means to an end. …

[The scriptural concept of] the nation of Israel refers to the abstract identity of the community, not to each and every individual Israelite. The same is true of the nations who inhabit the land. Hivites, Perizzites, Girgashites, and so on, does not refer to each and every person of those particular ethnicities individually; it refers to the community in which they participate and from which they draw their identity. So what does it mean to ḥerem an identity?

If ḥerem means “remove from use,” then removing an identity from use depends on what identity is used for. We suggest that the action is comparable to what we might try to accomplish by disbanding an organization. Doing so does not typically entail disposing of all the members, but it means that nobody is able to say “I am a member of X” anymore. After World War II, when the Allies destroyed the Third Reich, they did not kill every individual German soldier and citizen; they killed the leaders specifically and deliberately (compare to the litany of kings put to the sword in Joshua 10-13) and also burned the flags, toppled the monuments, dismantled the government and chain of command, disarmed the military, occupied the cities, banned the symbols, vilified the ideology, and persecuted any attempt to resurrect it — but most of the people were left alone, and most of those who weren’t were casualties of war. This is what it means to ḥerem an identity. …

In one sense, the identity needs to be removed so that the Canaanite nations cannot make use of it … because … it would … have negative consequences for the Israelite occupiers. …

More importantly, however, the identity needs to be removed so that Israel cannot make use of it. This is the essence of the threat that “they will become snares and traps for you.”[82] With non-Israelite identities coexisting alongside the Israelite identity, syncretism, appropriating foreign religious customs and beliefs, becomes a distinct possibility, bordering on inevitable. With a non-Israelite community identity nearby, it is possible that Israelites will marry outside their community and thus lose the Israelite identity marker and vanish. …

Communities of foreigners are allowed to remain among Israel (see, for example, the [Philistine] Kerethites and Pelethites that form David’s personal guards), but even if they are not inducted into the Israelite community they are still required to observe the covenant order.[83] … If foreigners observe the covenant order, they will not be tô ʿēbâ [out of order] and will not be a snare for the Israelites, and therefore there is no reason to ḥerem them.

Relating this to the idea of the whole of the promised land as a sacred space, no person who defiles that space should continue to dwell in the land of Israel:[84]

An interesting comparison can be drawn from Jesus’ cleansing of the temple. He “drives out”[85] both the buyers and sellers[86] because they are violating the zoning laws[87] of sacred space (by conducting human activities). It is likely that some corrupt practices were involved (he does call them thieves), but they are being evicted because their occupancy (not their deeds) was defiling (ṭāmēʾ) and contrary to the order (tôʿēbâ) of the sacred precinct.

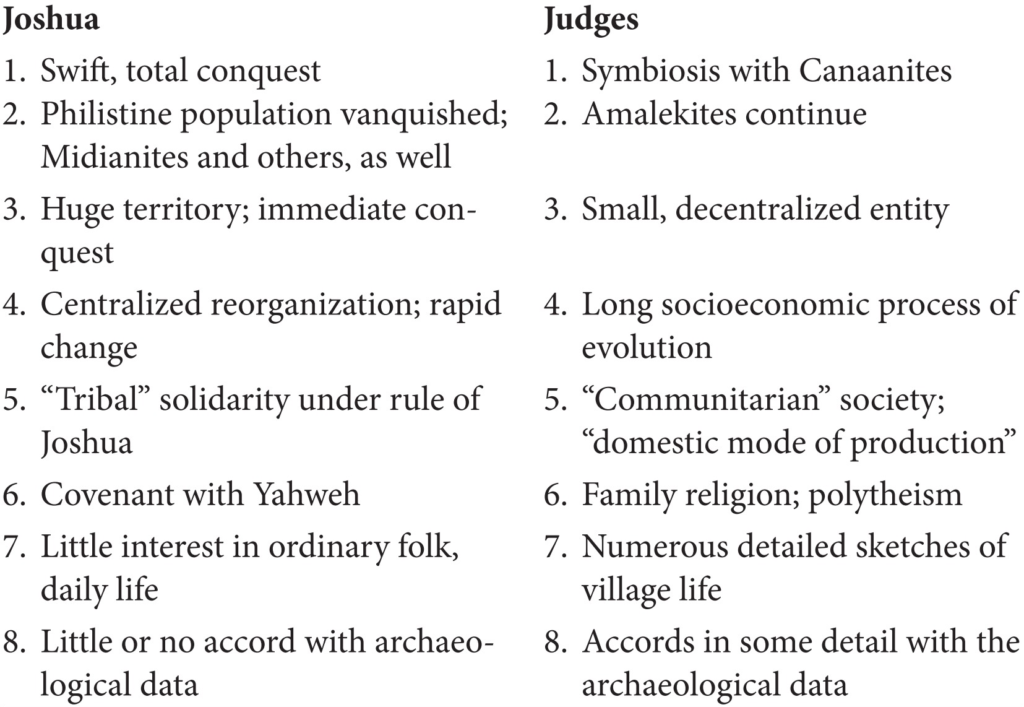

Assumption 2: That Joshua and Judges tell the same story. Although strongly discounting the account of the destruction of various cities in the book of Joshua as legitimate “history,” even the skeptical Dever concludes that “a selective reading of passages in Judges, plus Samuel, does accord well with the archaeological data.”[88]

He notes that of those sites west of Jordan that were “said to have been taken, that is, destroyed, thirty-four of them are listed in the book of Joshua but only three in Judges: Bezek, Jerusalem, and Hazor.”[89] By way of contrast, he also observes that the first chapter of Judges gives “a list of more than a dozen sites not conquered — in some cases sites (e.g., Hazor) that the book of Joshua claims had been destroyed.”[90]

In light of Walton’s more nuanced understanding of the Hebrew term ḥerem, is it possible that some of the cities of the Canaanites could have been “taken” in a way that did not entail significant destruction of the buildings or their inhabitants? If that were true, the characterization of Joshua as portraying “swift, total conquest” with populations being “vanquished” could be understood as something different than pure hyperbole. And the differences with Judges would be reduced. No doubt the two books are authored from different perspectives. Joshua’s priestly optimism and focus on the covenant would better fit the triumphant attitude of the Israelites as they entered the promised land than the focus on everyday life of the people settled in the hill country of Canaan during the several decades that followed.

Figure 9.Dever’s comparison of themes in Joshua and Judges[91]

In its picture of life in the Israelite settlements, Dever also sees historical value in the book of Judges, remarking that it “has the ring of truth about it”:[92]

The core of the narrative consists of stories about everyday life in the formative, pre-state era, when “there was no king in Israel [and] all the people did what was right in their own eyes.”[93] The portrait is of as much as two hundred years of struggles under charismatic leaders with other peoples in the land — of a long drawn-out process of socioeconomic, political, and cultural change. … In particular, several of the stories of everyday life in Judges are full of details with which any archaeologist is familiar. These would include Ehud’s upper chamber;[94] the palm tree where Deborah sat;[95] Gideon’s household (house of the father), with its oxen, threshing floor, winepress, household shrine, and village kinsmen and collaborators;[96] Jephthah and the elders of Israel;[97] dialectical variations and the shibboleth incident;[98] the Nazarites and nostalgia for simpler times;[99] Samson and the Philistines;[100] Micah’s household shrine;[101] and the annual agricultural feast and betrayals of the daughters of Shiloh.[102] … In slightly modified form, the biblical socioeconomic and societal terms can be correlated with the archaeological data.

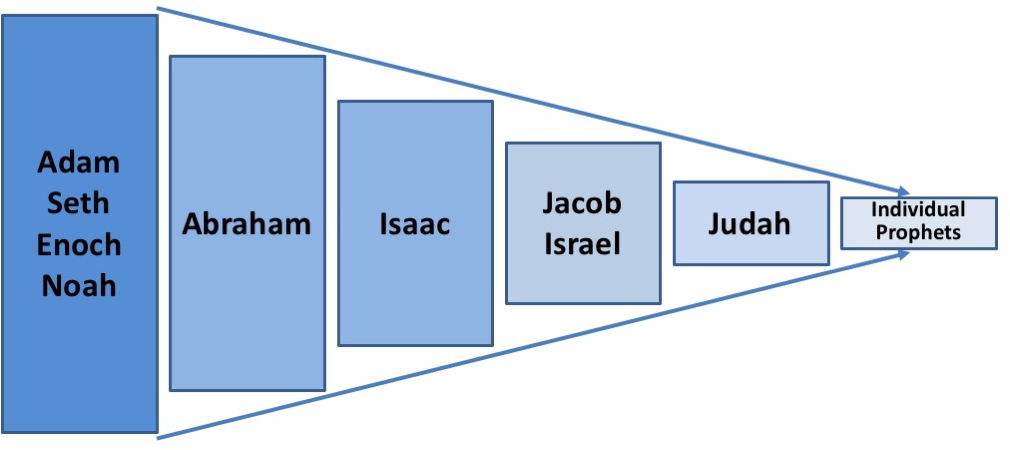

Figure 10. View of the Bible as a history with a continually narrowing perspective. With the kind permission of Stephen T. Whitlock

The Why

Genesis begins with the story of all humankind and ends with the Lord’s focus on a single family, the family of Abraham. The story of the Exodus and the settling of Canaan portrays the transformation of that family into a nation of covenant people. Although the Book of Mormon makes it clear that God did not forget Ephraim, Manasseh, and the scattered tribes of Israel, the Bible will eventually narrow its scope to the nation of Judah and the eventual birth of the Savior. But that is not the end of the story — God’s promise to Abraham was that in him “shall all families of the earth be blessed.”[103]

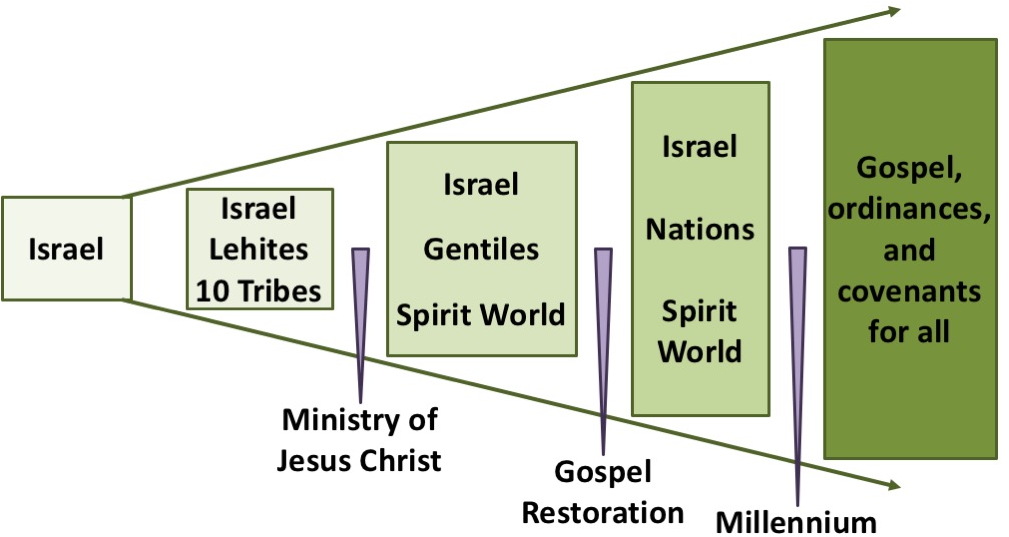

Figure 11. View of salvation history as a continually broadening perspective. With permission of Stephen T. Whitlock

The ministry of Jesus Christ was a watershed event that heralded the inauguration of a vast missionary effort that would broaden beyond Israel. The Gospel would be taken not only to the Gentile nations but also to the spirit world, as a witness that the Lord is “willing to make these things known unto all.”[104] The purpose of God’s restored Church is to prepare a faithful people that “will fill the world.”[105] In the millennial day we will see the complete fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham — all members of the human family who so desire will be bound together in a sealing chain stretching back to him, and through him back to our first parents, Adam and Eve.[106]

Long ago, Jewish sages anticipated the worldwide sweep of salvation when they prophesied that “Jerusalem is destined to be [as large] as the Land of Israel, and the Land of Israel [as large] as the whole world.”[107] Until that day comes, living faithfully in a world that is often indifferent to God and His law will sometimes prove challenging, as expressed in a Jewish folktale about Sodom:[108]

A righteous man arrived in the city, and went about telling people to repent. The more he was ignored, the louder his calls for repentance grew. One day, a young boy said to him, ‘Why do you continue yelling at people to change their behavior? You’ve been here a long time already, and you have affected no one.’ ‘When I first arrived,’ the man responded, ‘I hoped that my yelling would change the people of Sodom. Now I yell so that the people of Sodom don’t change me.'”

Of course, God is troubled not only by the treatment of believers by unbelievers, but also about whether even the best of His people understand what is required of them if the magnitude of their patience and graciousness toward their unbelieving neighbors is ever to begin to approach His own. The story is told of the visit of an idol worshipper who refused to honor the Lord for the bread he had received. Abraham “grew enraged at the man and rose and drove him away into the desert.” Seeing this, God rebuked him, saying: “Consider, one hundred and ninety-eight years, all the time that man has lived, I have borne with him and did not destroy him from the face of the earth. Instead I gave him bread to eat and I clothed him and I did not have him lack for anything… How did you come to… drive him out without permitting him to lodge in your tent even a single night?” At that, Abraham “swiftly brought [the man] back to his tent… and sent him away in peace the next morning.”[109]

The problem of taking “Egypt” and “Canaan” out of the Israelites so they would be fit to enter His presence still faces us today. Speaking in Nairobi about the temple that is soon to be constructed in Kenya, President Russell M. Nelson said, “I don’t know how long it will take to build that temple, but let’s have a little contest: See if you can build your lives to be ready and your ancestral documentation to be ready when the temple comes.”[110]

My gratitude for the love, support, and advice of Kathleen M. Bradshaw on this article. Thanks also to Jonathon Riley and Stephen T. Whitlock for valuable comments and suggestions.

Further Study

For an exhaustive and up-to-date review of archaeological findings bearing on the history of early Israel, see W. G. Dever, Beyond the Texts.

For insightful perspectives on the conquest of Canaan from an evangelical scholar, see J. H. Walton, et al., Lost World of the Israelite Conquest. See also his book outlining an Old Testament theology based on the centrality of God’s purpose to bring people into His presence (J. H. Walton, Old Testament Theology).

For an interview of John Walton about his book on the conquest of Canaan, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fbm_JSa9Hcw

For Book of Mormon KnoWhy’s relating to the book of Joshua, see these links:

- Why Did the Stripling Warriors Perform Their Duties “With Exactness”?

- Why Did the “Pride Cycle” Destroy the Nephite Nation?

For viewpoints on how peoples of different family origins became part of the covenant family in the Bible and the Book of Mormon, see:

For a perspective on the idea of “holy war” informed by the Book of Mormon, see:

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

Anderson, Gary A. "The cosmic mountain: Eden and its early interpreters in Syriac Christianity." In Genesis 1-3 in the History of Exegesis: Intrigue in the Garden, edited by G. A. Robins, 187-224. Lewiston/Queenston: Edwin Mellen Press, 1988.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Bartley, William Warren, II. 1962. The Retreat to Commitment. Second ed. La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1984. littp://www.arcliive.org/details/retreattocommitmOObart. (accessed May 5, 2018).

Benson, Ezra Taft. "The Book of Mormon—Keystone of our religion." Ensign 16, November 1986, 4-7. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/1986/11/the-book-of-mormon-keystone-of-our-religion?lang=eng. (accessed March 20, 2014).

Berlin, Adele. "A search for a new biblical hermeneutics: Preliminary observations." In The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-First Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference, edited by Jerrold S. Cooper and Glenn M. Schwartz, 195-207. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1996.

Berman, Joshua A. 2015. Searching for the historical Exodus (2 April 2015). In The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/joshua-berman-searching-for-the-historical-exodus-1428019901. (accessed March 29, 2018).

———. 2015. Was there an Exodus? In Mosaic Magazine. http://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/2015/03/was-there-an-exodus/. (accessed June 27, 2015).

———. Inconsistency in the Torah: Ancient Literary Convention and the Limits of Source Criticism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2017.

bin Gorion, Micha Joseph (Berdichevsky), and Emanuel bin Gorion, eds. 1939-1945. Mimekor Yisrael: Classical Jewish Folktales. 3 vols. Translated by I. M. Lask. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1976.

Blenkinsopp, Joseph. "The structure of P." The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 38, no. 3 (1976): 275-92. Structure of P.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Marco Carvalho, Larry Bunch, Tom Eskridge, Paul J. Feltovich, Chris Forsythe, Robert R. Hoffman, Matthew Johnson, Dan Kidwell, and David D. Woods. "Coactive emergence as a sensemaking strategy for cyber operations." Pensacola, FL: IHMC Technical Report, 2012.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., Marco Carvalho, Larry Bunch, Tom Eskridge, Paul J. Feltovich, Matthew Johnson, and Dan Kidwell. "Sol: An Agent-Based Framework for Cyber Situation Awareness." Künstliche Intelligenz 26, no. 2 (2012): 127-40.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. "The tree of knowledge as the veil of the sanctuary." In Ascending the Mountain of the Lord: Temple, Praise, and Worship in the Old Testament, edited by David Rolph Seely, Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Matthew J. Grey. The 42nd Annual Brigham Young University Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (26 October, 2013), 49-65. Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2013.

———. "Foreword." In Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture, edited by Matthew L. Bowen, ix-xliv. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2018.

Braude, William G., ed. Pesikta Rabbati: Discourses for Feasts, Fasts, and Special Sabbaths. 2 vols. Yale Judaica Series 28, ed. Leon Nemoy, Saul Lieberman and Harry A. Wolfson. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968.

Bunch, Larry, Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Robert R. Hoffman, and Matthew Johnson. "Principles for human-centered interaction design, part 2: Can humans and machines think together?" IEEE Intelligent Systems 30, no. 3 (May/June 2015): 68-75. http://www.jeffreymbradshaw.net/publications/30-03-HCC.PDF. (accessed March 15, 2016).

Dever, William G. Did God Have a Wive? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2005.

———. Beyond the Texts: An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2017.

Eagleton, Terry. 1983. Literary Theory: An Introduction. Anniversary ed. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Faulconer, James E. Scripture Study: Tools and Suggestions. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, Brigham Young University, 1999.

———. "Scripture as incarnation." In Historicity and the Latter-day Saint Scriptures, edited by Paul Y. Hoskisson, 17-61. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 2001. Reprint, in Faulconer, J. E. Faith, Philosophy, Scripture. Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, 2010, pp. 151-202.

———. "Response to Professor Dorrien." In Mormonism in Dialogue with Contemporary Christian Theologies, edited by Donald W. Musser and David L. Paulsen, 423-35. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2007.

Finkelstein, Israel, and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster, Touchstone, 2001.

Fishbane, Michael A. "The sacred center." In Texts and Responses: Studies Presented to Nahum H. Glatzer on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday By His Students, edited by Michael A. Fishbane and P. R. Flohr, 6-27. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1975.

Freedman, H., and Maurice Simon, eds. 1939. Midrash Rabbah 3rd ed. 10 vols. London, England: Soncino Press, 1983.

Friedman, Richard Elliott. The Exodus: How It Happened and Why It Matters. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2017.

Gee, John. "Edfu and Exodus." In Temple Insights: Proceedings of the Interpreter Matthew B. Brown Memorial Conference ‘The Temple on Mount Zion,’ 22 September 2012, edited by William J. Hamblin and David Rolph Seely. Temple on Mount Zion Series 2, 67-82. Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation/Eborn Books, 2014.

Hendel, Ronald S. "Tangled plots in Genesis." In Fortunate the Eyes that See: Essays in Honor of David Noel Freedman, edited by Astrid B. Beck, Andrew H. Bartelt, Paul R. Raabe and Chris A. Franke, 35-51. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1995.

Hieke, Thomas. 2004. Review of Myung Soo Suh ‘The Tabernacle in the Narrative History of Israel from the Exodus to the Conquest’. In Society of Biblical Literature. http://blog.thomashieke.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Suh-Tabernacle.pdf. (accessed April 8, 2018).

Hinckley, Gordon B. "’If ye are prepared ye shall not fear’." Ensign 35, November 2005, 60-62.

Hoffmeier, James K. Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence fot eh Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition. New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Homan, Michael M. "The divine warrior in his tent: A military model for Yahweh’s tabernacle." Bible Review 16, no. 6 (December 2000). https://members.bib-arch.org/bible-review/16/6/8. (accessed March 31, 2018).

———. ‘To Your Tents, O Israel!’: The Terminology, Function, Form, and Symbolism of Tents in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 12, ed. Baruch Halpern, M. H. E. Wieippert, Th. P. J. Van Den Hout and Irene J. WInter. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

———. "Review of Myung Soo Suh, The Tabernacle in the Narrative History of Israel from the Exodus to the Conquest." The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 5 (2005). http://www.jhsonline.org/reviews/review133.htm. (accessed April 13, 2018).

———. 2018. The tabernacle in its ancient Near Eastern context (March 6, 2018). In The Torah.com: A Historial and Contextual Approach. https://thetorah.com/the-tabernacle-in-its-ancient-near-eastern-context/. (accessed March 31, 2018).

Klein, Gary, Brian M. Moon, and Robert R. Hoffman. "Making sense of sensemaking: 1: Alternative perspectives." IEEE Intelligent Systems, July/August 2006, 70-73.

———. "Making sense of sensemaking: 2: A macrocognitive model." IEEE Intelligent Systems, November/December 2006, 88-92.

Kugel, James L. How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. New York City, NY: Free Press, 2007.

LaCocque, André. The Captivity of Innocence: Babel and the Yahwist. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2010.

Levenson, Jon D. "The temple and the world." The Journal of Religion 64, no. 3 (1984): 275-98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1202664. (accessed July 2).

Morales, L. Michael. The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus. Biblical Tools and Studies 15, ed. B. Doyle, G. Van Belle, J. Verheyden and K. U. Leuven. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 2012.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E., and James C. VanderKam, eds. 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 37-82. Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Noegel, Scott B. "Moses and magic: Notes on the book of Exodus." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 24 (1996): 45-59. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/dee0/913828e224942b51f4c6863344375b82ecc2.pdf. (accessed March 21, 2018).

———. "The Egyptian origin of the Ark of the Covenant." In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geosciance, edited by Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 223-42. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2015. http://jewishstudies.rutgers.edu/faculty/core-faculty-information/gary-a-rendsburg/132-publications-of-gary-a-rendsburg. (accessed March 19, 2018).

———. 2017. The Egyptian “magicians” (30 March 2017). In https://thetorah.com/the-egyptian-magicians/. (accessed March 19, 2018).

Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992. https://archive.org/details/egyptcanaanisrae00redf. (accessed May 3, 2018).

Rendsburg, Gary A. "The Egyptian Sun-God Ra in the Pentateuch." Henoch 10 (1988): 3-15.

———. "The date of the Exodus and the conquest/settlement: The case for the 1100’s." Vetus Testamentum 42 (1992): 510-27.

———. "The early history of Israel." In Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons: Studies in Honor of Michael C. Astour on His 80th Birthday, edited by Gordon Douglas Young, Mark W. Chavalas and Richard E. Averbeck, 433-53. Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 1997.

———. "Moses as equal to Pharaoh." In Text, Artifact, and Image: Reveling Ancient Israelite Religion, edited by Gary A Beckman and Theodore J. Lewis. Brown Judaic Studies 346, 201-19. Providence, RI: Brown Judaic Studies, 2006. http://jewishstudies.rutgers.edu/faculty/core-faculty-information/gary-a-rendsburg/132-publications-of-gary-a-rendsburg. (accessed March 19, 2018).

———. "Moses the magician." In Israel’s Exodus in Transdisciplinary Perspective: Text, Archaeology, Culture, and Geosciance, edited by Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Schneider and William H. C. Propp. Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences, 243-58. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2015. http://jewishstudies.rutgers.edu/faculty/core-faculty-information/gary-a-rendsburg/132-publications-of-gary-a-rendsburg. (accessed March 19, 2018).

———. 2015. Reading the plagues in their ancient Egyptian context (10 January 2015). In The Torah.com: A Historical and Contextual Approach. http://thetorah.com/plagues-in-their-ancient-egyptian-context/. (accessed January 28, 2018).

———. 2016. YHWH’s war against the Egyptian sun-god Ra: Reading the plagues of locust, darkness, and firstborn in their ancient Egyptian context. In TheTorah.com: A Historical and Contextual Approach. http://thetorah.com/yhwhs-war-against-the-egyptian-sun-god-ra/. (accessed January 28, 2018).

———. n.d. The pharaoh of the Exodus — Rameses III. In The Torah.com: A Historical and Contextual Approach. http://thetorah.com/the-pharaoh-of-the-exodus-rameses-iii/. (accessed March 28, 2018).

Sherman, Phillip Michael. Babel’s Tower Translated: Genesis 11 and Ancient Jewish Interpretation. Biblical Interpretation Series 117, ed. Paul Anderson and Yvonne Sherwood. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Words of Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1980. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/words-joseph-smith-contemporary-accounts-nauvoo-discourses-prophet-joseph/1843/21-may-1843. (accessed February 6, 2016).

———. Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2007.

———. 1902-1932. History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Documentary History). 7 vols. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1978.

Suh, Myung Soo. The Tabernacle in the Narrative History of Israel from the Exodus to the Conquest. Studies in Biblical Literature 50. New York City, NY: Lang, 2003.

Taylor, John. The Government of God. Liverpool, England: S. W. Richards, 1852. Reprint, Heber City, UT: Archive Publishers, 2000.

Telushkin, Joseph. Biblical Literacy. New York City, NY: William Morrow and Company, 1997.

Townsend, John T., ed. Midrash Tanhuma. 3 vols. Jersey City, NJ: Ktav Publishing, 1989-2003.

Uchtdorf, Dieter F. "Come, Join with Us." Ensign 43, November 2013, 21-24. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/2013/11/saturday-morning-session/come-join-with-us?lang=eng. (accessed November 11, 2015).

Walch, Tad. 2018. ‘Dowry is not the Lord’s way’: In Kenya, LDS President Nelson says tithing breaks poverty cycle (16 April 2018). In Deseret News. https://www.deseretnews.com/article/900016023/dowry-is-not-the-lords-way-in-kenya-lds-president-nelson-says-tithing-breaks-poverty-cycle.html. (accessed April 17, 2018).

Walton, John H. Old Testament Theology for Christians: From Ancient Context to Enduring Belief. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017.

Walton, John H., and J. Harvey Walton. The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest: Covenant, Retribution, and the Fate of the Canaanites. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, IVP Academic, 2017.

Wright, Nicholas Thomas. "How can the Bible be authoritative?" Vox Evangelica 21 (1991): 7-32. http://www.ntwrightpage.com/Wright_Bible_Authoritative.htm. (accessed April 7).

Wyatt, Nicolas. "’Water, water everywhere…’: Musings on the aqueous myths of the Near East." In The Mythic Mind: Essays on Cosmology and Religion in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicholas Wyatt, 189-237. London, England: Equinox, 2005.

Zakovitch, Yair. "Inner-biblical interpretation." In Reading Genesis: Ten Methods, edited by Ronald S. Hendel, 92-118. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. Genesis: The Beginning of Desire. Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Endnotes

The most comprehensive discussion of their background is that of J. K. Hoffmeier, Ancient Israel in Sinai. Hoffmeier is an evangelical scholar but also a well-trained Egyptologist and the director of a significant excavation project in the Egyptian Delta. After an exhaustive survey of Egyptian literature and culture, as well as the topography of the Delta and Sinai, he is able to document only a few sites that might be identified with the biblical account of the sojourn of the Hebrews in Egypt and their itinerary after they supposedly escaped from slavery. The Rameses of the biblical texts (Exodus 1:11) has long been located at Pi-Ramesses, which flourished circa 1270–1120. Pithom (Exodus 1:11) is almost certainly Tell el-Maskhuta, excavated several times and known to have been occupied in New Kingdom times. Biblical Succoth (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 33:3–5) was probably in the Wadi Tumilat, where there are several possibilities for the site’s location. Biblical Etham (Exodus 13:20), on the edge of the wilderness, might be located in the Lake Timsah region, near Qantara. Hoffmeier’s own contribution is to be acknowledged. He has shown that his site of Tell el-Borg, on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, is probably the biblical fortress of Migdol (Exodus 14:20). Beyond that, Hoffmeier has a long excursus on the Red (“Reed”) Sea crossing and the years of wandering in the wilderness of Sinai. Yet in the end he has no archaeological evidence, any more than Israeli archaeologists had in their determined search in the 1970s. He can only conclude that the events narrated in Exodus and Numbers as historical might have happened.

The fact is that the Merenptah inscription tells us a great deal about early Israel — and from an independent point of view that cannot be faulted for biblical bias. At minimum, we learn that:

- There existed in Canaan by 1210 at latest a cultural and probably a political entity that called itself “Israel” and was known to the Egyptians by that name.

- This Israel was well enough established by that time among the other peoples of Canaan to have been perceived by Egyptian intelligence as a possible challenge to Egyptian hegemony.

- This Israel did not constitute an organized state like others in Canaan but consisted rather of loosely affiliated peoples, that is, an ethnic group.

- This Israel was not located in the lowlands, under Egyptian domination, but in the more remote central hill country, on the frontier.

What all current models used to explain the phenomenon of early Israel have in common is that they focus on indigenous origins somewhere within Greater Canaan, and they portray an ethnic group that somehow embraces many elements of the local population. The remaining debate among specialists largely concerns the percentages of such groups as local refugees, displaced subsistence farmers, various dissidents and dropouts, former pastoral nomads, and perhaps even a small exodus group, whether or not they had actually even been in Egypt. The old conquest model is gone forever.

We have already stressed the heterogeneous nature of the people of Late Bronze Age Canaan, their longtime adaptation to the shifting frontier, and their growing restiveness by the end of the period. It should, therefore, be no surprise that we will now advocate an explicit model for the Iron I hill-country colonists—Proto-Israelites—that accounts for a variety of groups, all of them dissidents of one sort or another. Among them would be included the following: (1) urban dropouts—people seeking to escape from economic exploitation, bureaucratic inefficiency and corruption, taxation, and conscription; (2) Habiru and other social bandits (Hobsbawm’s term), rebels already in the countryside, some of them highwaymen, brigands, former soldiers and mercenaries, or entrepreneurs of various sorts—freebooters, in other words; (3) refugees of many kinds, including those fleeing Egyptian injustice, displaced villagers, impoverished farmers, and perhaps those simply hoping to escape the disaster that they saw coming as their society fell into decline; (4) local pastoral nomads, including some from the eastern steppes or Transjordan (Shasu), even perhaps an “exodus group” that had been in Egypt among Asiatic slaves in the Delta. All of these peoples were dissidents, disgruntled opportunists ready for a change. For all these groups, despite the obstacles to be overcome, the highland frontier would have held great attraction: a new beginning.

The idea of early Israel as a motley crew is not all that revolutionary. The biblical tradition, although much later, remembers such diverse origins. It speaks not only of Amorites and Canaanites in close contact with Israelites but also Jebusites, Perizzites, Hivites (the latter probably Neo-Hittites), and others. All could have been part of the Israelite confederation at times. The Gibeonites and Shechemites, for instance, are said to have been taken into the Israelite confederation by treaty. Some were born Israelites; others became Israelites by choice. The confederation’s solidarity, so essential, was ideological, rather than biological—”ethnicity.” …

As for leadership, or external sources of power, it is noteworthy that the Amarna letters mention chiefs of the Habiru. The Hebrew Bible, of course, attributes the role of leadership first to Joshua and then to his successors, the judges. These early folk heroes were essentially successive charismatic military leaders who are portrayed in Judges precisely as men (and one woman) of unusual talents who were able to rally the tribes against the Canaanites. Direct archaeological evidence for any of these specific persons is lacking, of course, since the archaeological record without texts is anonymous (although not mute). But the Iron I hill-country villages do exhibit a remarkable homogeneity of material culture and evidence for family and clan social solidarity. Such cohesiveness—a fact on the ground—had to have come from somewhere.

As modern biblical scholarship gained momentum, studying the Bible itself was joined with, and eventually overshadowed by, studying the historical reality behind the text (including how the text itself came to be). In the process, learning from the Bible gradually turned into learning about it.

Such a shift might seem slight at first, but ultimately it changed a great deal. The person who seeks to learn from the Bible is smaller than the text; he crouches at its feet, waiting for its instruction or insights. Learning about the text generates the opposite posture. The text moves from subject to object; it no longer speaks but is spoken about, analyzed, and acted upon. The insights are now all the reader’s, not the text’s, and anyone can see the results. This difference in tone, as much as any specific insight or theory, is what has created the great gap between the Bible of ancient interpreters and that of modern scholars.

… was not in deciding what the scriptures portray, but in what they say. They do not take the scriptures to be picturing something for us, but to be telling us the truth of the world, of its things, its events, and its people, a truth that cannot be told apart from its situation in a divine, symbolic ordering [Cf. A. G. Zornberg, Genesis, pp 31-32].

Of course, that is not to deny that the scriptures tell about events that actually happened. … However, premodern interpreters do not think it sufficient (or possible) to portray the real events of real history without letting us see them in the light of that which gives them their significance — their reality, the enactment of which they are a part — as history, namely the symbolic order that they incarnate. Without that light, portrayals cannot be accurate. A bare description of the physical movements of certain persons at a certain time is not history (assuming that such bare descriptions are even possible).

Most notably these accounts tend to exaggerate the magnitude of the victory and the scale of the slaughter inflicted on the enemies. This does not mean that the accounts are lies in the sense that we mean when we call them propaganda; both author and audience understand the genre, so there is no intention to deceive. But the accounts are primarily interested in interpreting the event and only secondarily interested in documenting the phenomena that accompanied it.

Normally, in order to serve whatever purpose the interpretation is employed for (typically in the ancient Near East, the legitimation of the ruler who commissioned it) the event had to actually occur more or less as described; a king would not defend his right to rule based on a battle that never took place. The same is true of Israelite literature, including the conquest in Joshua. We should assume that a military campaign of some kind occurred, and since the record is inspired we should assume that the writer’s interpretation of the event is accurate, at least insofar as it claims to represent the purposes of God. But the actual details of the totality of the destruction or the quantity of victims is likely couched in rhetorical hyperbole, in accordance with the expectations of the genre.

As P. M. Sherman, Babel’s Tower, p. 45 argues, we should not be overly concerned “with direction of influence; rather [our] interest is in the type of influence other biblical texts (whatever the chronological or canonical relationship … ) exert on the interpretation” of the narratives of exegetical focus. Scripture readers encounter these narratives “in the midst of a whole host of other [scriptural] narratives, all of which (or none of which) could serve as potential inter-texts for reading [the Hexateuch].” Rabbinical readers recognized this way of understanding the Hebrew Bible when they wrote: “There is no before or after in the Torah” (Cited in ibid., p. 43. From Talmud of Jerusalem Megillah 1:5; Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 6b (with reference to when the Passover should be celebrated). Compare the point of view of literary theorists such as Terry Eagleton (T. Eagleton, Literary Theory, p. 67):

The literary work itself exists merely as … a set of “schemata” or general directions, which the reader must actualize. As the reading process proceeds, however, these expectations will themselves be modified by what we learn, and the hermeneutical circle — moving from part to whole and back to part — will begin to revolve … What we have learned on page one will fade and become “foreshortened” in memory, perhaps to be radically qualified by what we learn later. Reading is never a straightforward linear movement, a merely cumulative affair; our initial speculations generate a frame of reference within which to interpret what comes next, but what comes next may retrospectively transform our original understanding, highlighting some features of it and backgrounding others. As we read on we shed assumptions, revise beliefs, make more and more complex inferences and anticipations; each sentence opens up a horizon which is confirmed, challenged, or undermined by the next. We read backwards and forwards simultaneously, predicting and recollecting, perhaps aware of other possible realizations of the text which our reading has negated. Moreover, all of this complicated activity is carried out on many levels at once, for the text has “backgrounds” and “foregrounds,” different narrative viewpoints, alternative layers of meaning between which we are constantly moving.

Of course, the process of “sensemaking” (G. Klein et al., Making Sense 1; G. Klein et al., Making Sense 2) is not confined to reading, but is pervasive in any human activities intent on understanding complex phenomena (e.g., J. M. Bradshaw et al., Sol; J. M. Bradshaw et al., Coactive emergence as a sensemaking strategy for cyber operations; L. Bunch et al., Principles for HCI Interaction Design 2).

Neither should the idea be disturbing to modern readers that some of the stories in the Hexateuch, as we have them today, might “be read as a kind of parable” (J. Blenkinsopp, The structure of P, p. 284) — its account of the historical events shaped with specific pedagogical purposes in mind. “If this is so,” writes Blenkinsopp, “it would be only one of several examples in P [one of the presumed redactors of the the Old Testament] of a paradigmatic interpretation of events recorded in the earlier sources with reference to the contemporary situation” (ibid., p. 284). More simply put, Nephi himself openly declared: “I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning” (1 Nephi 19:23). Indeed, Nephi left us with significant examples where he deliberately shaped his explanation of the Exodus in order to help his hearers understand how they applied to their own situations (E.g., 1 Nephi 4:2, 17:23-44).

“[A]ny conceptual framework which merely purports to reconstruct events ‘as they really were’ (Ranke),” writes Michael Fishbane, “is historicistic, and ignores the thrust of [the Bible’s] reality. For the Bible is more than history. It is a religious document which has transformed memories and records in accordance with various theological concerns” (M. A. Fishbane, Sacred Center, p. 5). André LaCocque has described how the Bible “attributes to historical events (like the Exodus, for instance) a paradigmatic quality” (A. LaCocque, Captivity of Innocence, p. 71).

Perhaps of equal significance is the request of the tribes of Reuben, Gad, and half the tribe of Manasseh to receive inheritances on the east side of the Jordan, rather than dwelling with the other tribes within the land of Canaan (Numbers 32) and the later controversy over the ambiguous meaning of the “altar of testimony” they built just to the west of the Jordan crossing (Joshua 22:10-34). Although the controversy was eventually settled to the satisfaction of all, the passage hints at the idea that “the land of [the] possession” of the two and a half tribes might be thought of as “unclean” and raises the question as to whether they would be better served if they came “unto the land of the possession of the Lord, wherein the Lord’s tabernacle dwelleth, and take possession among us” (Joshua 22:19), i.e., among the rest of the tribes who lived across the river in Canaan proper. Note that in this account only the western tribes living in Canaan itself are described as the “children of Israel” (Joshua 22:32-33), “to the exclusion of the eastern tribes” (H. W. Attridge et al., HarperCollins Study Bible, Commentary on Joshua 22:11). The episode recalls how the Israelites had once “stood afar off” (20:18, 21) from Sinai, contrary to Moses’ exhortations, and how in return the Lord commanded that the Tabernacle should later be “pitched … without the camp [of Israel], afar off” (Exodus 33:7).

Israel, co-identified with Yahweh through its holy status as the people of the covenant, is the embodiment of cosmic order. In contrast, the Canaanites are agents of chaos by virtue of their position outside the covenant … ; they are not in conformity with Yahweh’s covenant order, though they are also not expected to be. This status is emphasized for rhetorical purposes by their profile in Israel’s literature as subhuman barbarians. The Israelite nation is holy, co-identified with Yahweh and the cosmic order. The Canaanite nations are thematically related to cosmic chaos. The persistent emphasis of the conquest is to drive out the people of the land; thus the conquest thrusts chaos aside in order to make a space in which order will be established. When stated in this way, it becomes very apparent what the conquest is: a thematic recapitulation of the creation account in Genesis 1, where chaos was driven away to establish order. …

[The] point of both the [account of the Creation and the account of the Conquest] is not on the combat or on the enemy, but on the results following the victory, that is, what the deity does after the obstacle of chaos has been removed. In Genesis 1 the objective is rest (sabbath), which does not mean relaxation but rather signifies God’s ongoing action of maintaining and sustaining the cosmic order. In the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings), the objective is “placing the name.” To further cement the parallel, the conquest is completed when its objective of preparation is finished and God finally does place his name in the temple of Jerusalem (1 Kings 9:3), a building explicitly full of Edenic imagery that in turn symbolizes the cosmic order (J. D. Levenson, Temple and World, p. 288): “The temple and the world stand in an intimate and intrinsic connection. The two projects cannot ultimately be distinguished or disengaged. … Sabbath and sanctuary partake of the same reality.” The establishment of the original cosmic order in Genesis, and the establishment of the covenant order in a process that spans Moses to Solomon, are both part of Yahweh’s ongoing project of creation.

32 And after they had crossed the river Jordan he did make them mighty unto the driving out of the children of the land, yea, unto the scattering them to destruction.

33 And now, do ye suppose that the children of this land, who were in the land of promise, who were driven out by our fathers, do ye suppose that they were righteous? Behold, I say unto you, Nay.

34 Do ye suppose that our fathers would have been more choice than they if they had been righteous? I say unto you, Nay.

35 Behold, the Lord esteemeth all flesh in one; he that is righteous is favored of God. But behold, this people had rejected every word of God, and they were ripe in iniquity; and the fulness of the wrath of God was upon them; and the Lord did curse the land against them, and bless it unto our fathers; yea, he did curse it against them unto their destruction, and he did bless it unto our fathers unto their obtaining power over it.

36 Behold, the Lord hath created the earth that it should be inhabited; and he hath created his children that they should possess it.

37 And he raiseth up a righteous nation, and destroyeth the nations of the wicked.

38 And he leadeth away the righteous into precious lands, and the wicked he destroyeth, and curseth the land unto them for their sakes.

39 He ruleth high in the heavens, for it is his throne, and this earth is his footstool.

40 And he loveth those who will have him to be their God. Behold, he loved our fathers, and he covenanted with them, yea, even Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; and he remembered the covenants which he had made; wherefore, he did bring them out of the land of Egypt.

Of course, this does not mean that the actual historical people of Canaan were incapable of sin because they were outside the covenant. Sodom (accused of sin in Gen 13:13) was outside the covenant too (see also the argument of Romans 5:13–19), but the conquest account is not a technical theological treatise on how sin works (what systematic theologians call hamartiology). The historical people of Canaan were not actually subhuman chaos monsters any more than they were actually incestuous bestiophiles. The purpose of the conquest narrative is not to describe the literal nature of the literal people but to describe what is happening to them in such a way that the nature of the event can be properly understood. They were sinners (as all humanity is), but that is not the reason why the conquest was happening to them. They were being treated like chaos creatures, not treated like sinners, so the text depicts them as if they were chaos creatures (by means of the trope of invincible barbarians) to make clear what is actually going on.