An Old Testament KnoWhy[1]

relating to the reading assignment for

Gospel Doctrine Lesson 22: “The Lord Looketh on the Heart”

(1 Samuel 9-11; 13; 15-17) (JBOTL22A)

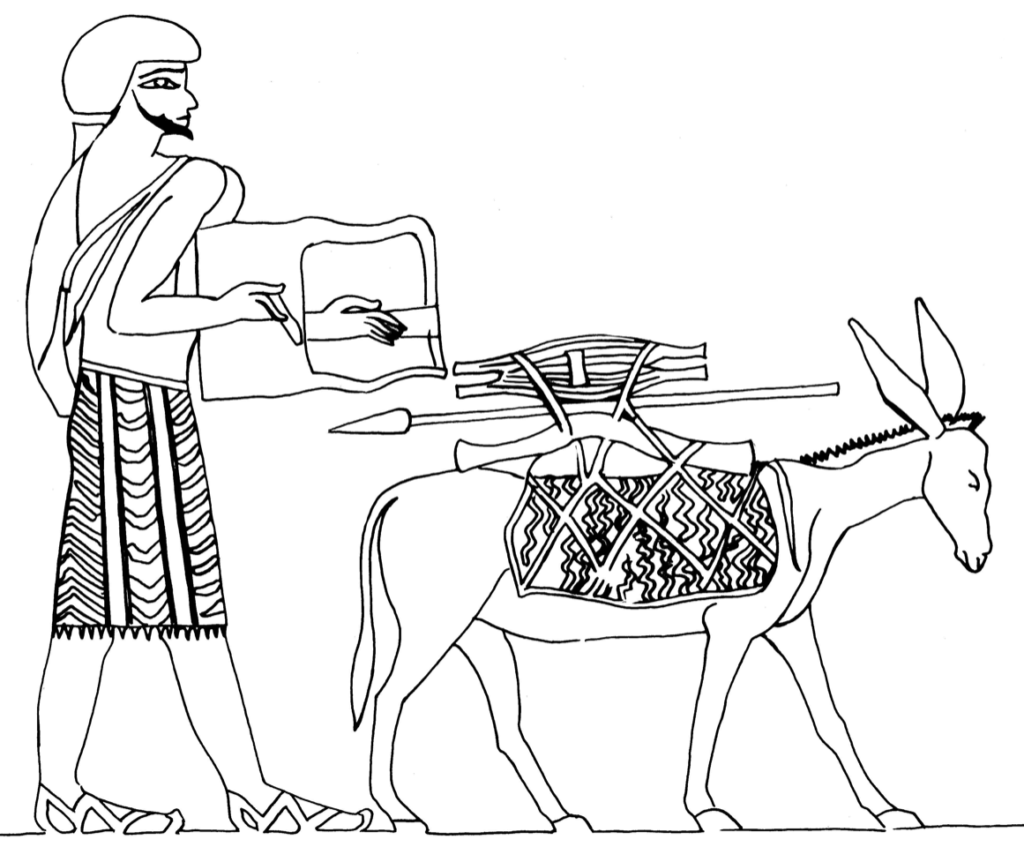

Figure 1. Lyrist from the tomb-painting of Khnumhotep II, Beni-Hasan, Egypt. Twelfth Dynasty, ca. 1900 BCE[2]

Question: What was the religious role of music in the life and times of David?

Summary: From the earliest times, music has played a central role in religion. The book of Samuel is a good example. Before Saul became king, music enabled the Spirit of the Lord to come upon him in the company of prophets;[3] later, in Saul’s misery, David’s harp — or, more accurately, lyre (Hebrew kinnôr[4]) — invited the Spirit into his palace once more.[5] Later, in likeness of other nations in the ancient Near East, music and dance became an inseparable part of the institution of kingship in Israel.[6] The Psalms, in a tradition that stretches back to David, contain some of the most significant prophecies of scripture and became the backbone of temple liturgy.[7] In this article, we will explore all these themes and will finish with examples of how the combination of inspired singing and playing continue as important mainstays of the religious life of the Saints today.

The Know

Music, and the lyre in particular, is credited in the Bible “with the ability to enable communication between the spiritual and natural worlds.”[8] The biblical usage of musical instruments is attributed to Jubal, a descendant of Cain, who is described as the ancestor of all who play “the lyre and the pipe.”[9] According to Hugh Nibley, Jubal’s name is the source of our word “jubilee,” and “means ‘to sing, to rejoice, to jubilate’ and the like.”[10] So important were Jubal’s musical gifts, that they were included in a short list of essential components of city life: “animal husbandry (Jabal[11]), arts (Jubal[12]), craftsmanship (Tubal-Cain[13]), and, it appears, law”[14] — all four being seen in concert with the unfortunate rise of “secret combinations” in the book of Moses (Lamech[15]).

Consistent with these harbingers in the first few chapters of Genesis, Jewish and Muslim sources often described musical developments during the patriarchal age in negative terms. For example, The Sethites and the Cainites (from the second temple period) speaks of these innovators as “evil and disorderly” men who, at the direction of the “Malicious One,” discovered “false music and dances and musical instruments.”[16] The music that “led them into confusion” is said to have had a “prominent role … in the seduction of the Sethite men by the Cainite women.”[17] The medieval Jewish scholar Rashi asserts that Jubal used these instruments ” to play music for idolatry.”[18]

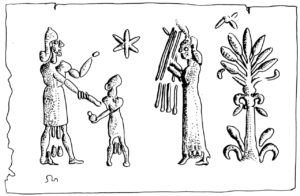

Figure 2. “Harp treaty.” Drawing based on an unprovenanced Mesopotamian cylinder seal, ca. fourteenth century BCE[19]

The objections in Jewish tradition to the combination of certain forms of music and worship would have been a natural reaction to the pagan religious practices of Israel’s neighbors. For example, in some parts of the ancient Near East, the “divine lyre,”[20] with a history traceable to ca. 3000 BCE, was sometimes considered a minor deity itself, and received “offerings of animal sacrifice, spices, oil, fruit, or jewelry.”[21] In addition, solemn oaths were sometimes taken on one or more musical instruments. For example, the figure shown above has been interpreted as a “treaty agreement; a king shakes hands with a smaller figure, presumably a client ruler, behind whom a musician, of equal stature to the king, plays an upright harp. Presumably the music somehow served to bind the agreement.”[22]

Despite the critical stance of some strands of Jewish tradition, the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Psalms speak to the important and positive roles of music. This article will examine the following episodes and subjects:

- Saul among the prophets — and their music;

- David plays the lyre before Saul;

- David and the Psalms;

- The women of Israel praise David in song;

- David dances before the Lord;

- Music and the institution of kingship;

- Musical management in the temple of Solomon.

Figure 3. Tissot: Saul prophesies among the prophets

Saul among the prophets — and their music. In the Book of Mormon, Mosiah’s predictions of the likely abuses of the institution of kingship are accepted by most of the people even though the reigns of Mosiah and his father Benjamin had been successful in every measure. In place of kingship, a system of judges was created whereby leaders were to rule according to God’s law rather than man’s whim.[23]

In 1 Samuel 8-9, it is precisely the opposite story. The people pressed for a king to replace the system of judges and, despite strong prophetic warnings from Samuel[24] and the Lord’s (consoling?) words to him that “they have not rejected thee, but they have rejected me,”[25] the voice of the people prevailed and Samuel was directed to anoint Saul as king.

Saul’s name (meaning “the requested one”) ironically reflects the fact that in their request for a king Israel got exactly what they asked for — at first for good and later for ill. In retrospect, Saul’s rule seems “doomed from the beginning. … [His] kingship is characterized by wrong turns and misperceptions.” He “must meander about, looking for lost she-asses, until he is ‘found’[26] — and even then he is only anointed after being brought out from having ‘hidden himself among the gear.’[27] Such a beginning[, though it might be viewed mistakenly at first blush as a hopeful augur of humility,] is hardly auspicious. On the other hand, he is physically imposing and a great warrior, and even, to the surprise of his people, can at times be seized by the spirit of God ‘like-a-prophet.'”[28]

The encounter of Saul with the company of prophets can be compared with “the story told in Numbers about Yahweh coming down to talk with Moses and seventy elders, and to put on the seventy some of the spirit that was already on Moses.[29] When this happened, the elders ‘prophesied'”[30] —the same Hebrew verb is used with respect to the company of prophets described in 1 Samuel 10:10.

Figure 4. Philistine cult stand in terra cotta from Ashdod decorated with five figures, four of which appear to be playing musical instruments: “cymbals, double pipe, lyre, and tambourine,” 11th-10th century BCE[31]

Prior to his first meeting with the company of prophets, “God gave [Saul] another heart,”[32] enabling the “spirit of God [to come] upon him” (temporarily at least) so that he could prophesy among them.[33] They came down, as Samuel had predicted, “from the high place with a psaltery, and a tabret, and a pipe, and a harp, before them.”[34] Although the text does not elaborate further, the detail at least helps us understand that music was understood to be an important accompaniment to prophecy. The reference also anticipates the Spirit-filled words that David will sing later as he plays his harp before Saul.[35]

David plays the lyre before Saul. As Saul repeatedly defies the instructions of Samuel and the law of the Lord, the Spirit withdraws from him.[36] The Lord tells Samuel that he must seek out a new king and anoint him secretly.[37] The same Spirit that has left Saul will now fall upon David.

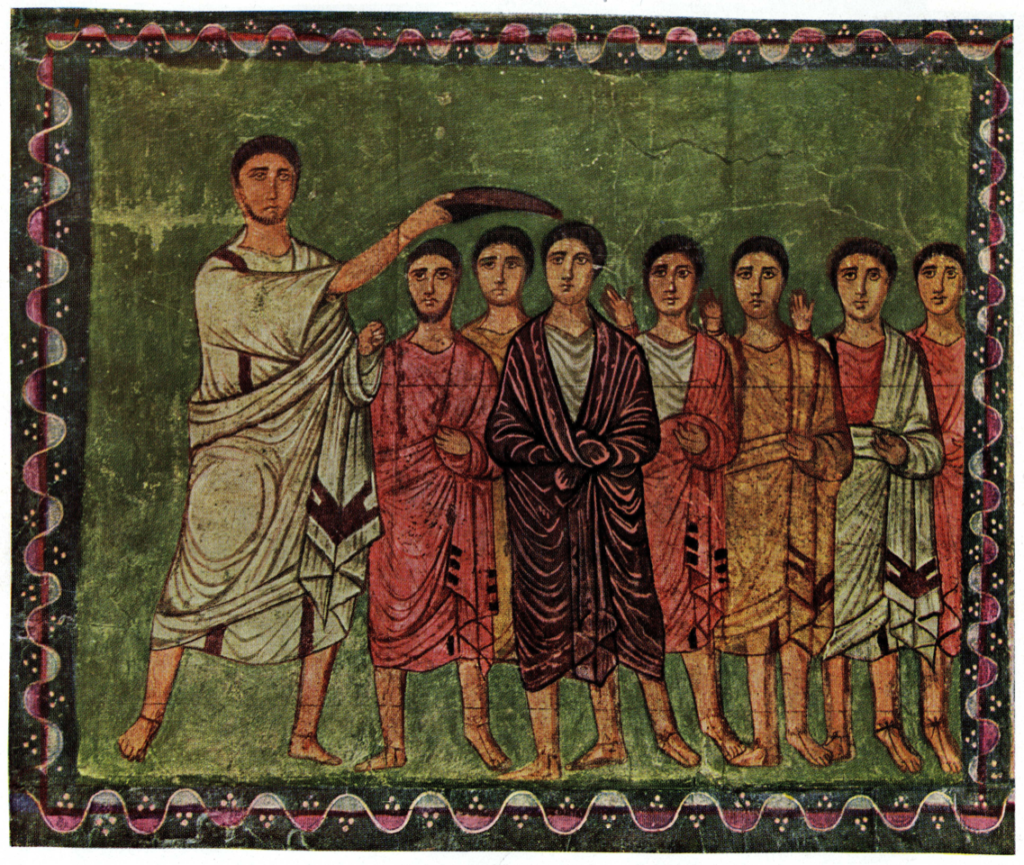

Figure 5. Samuel anoints David. Dura Europos Synagogue, ca. AD 254

Anointing, followed by an outpouring of the Spirit, is documented as part of the rites of kingship in ancient Israel.[38] For example, Isaiah attributes the presence of the Spirit of the Lord to a prior messianic anointing — the anointing oil, like divine breath at Creation, being a symbol of new life: “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me; because the Lord hath anointed me.”[39] Note that it was immediately after Samuel anointed David that “the Spirit of the Lord came upon David from that day forward.”[40]

Figure 6. Rembrandt: David playing before Saul, 1658-1659.

With this discussion as background we can better understand the story of David’s beneficial employ of music to dispel the evil spirit that plagued Saul.[41] An ancient reader of the story would have recoiled in disgust at a trivialized description of David’s practice of a divine art as “music therapy.”[42] The view of the Bible is that the effectiveness of the music was not due primarily to David’s diligent hours of mastering musical technique in the field as a shepherd, but rather to the God who infused the songs with spiritual power as a gift to His faithful servant. As Saul ultimately came to know, David’s most important qualifications as a “cunning player”[43] — and later as a rival for the throne — were not derived from his inherent talents, but rather “because the Lord was with him.”[44]

Through the Spirit of the Lord, David was enabled to sing the word of the Lord, and the prominence of the lyre in his biography alludes to “an older situation in which the instrument contributed … to the process, as a divine mouthpiece,”[45] the second witness in a revelatory duet performed by “holy hymning”[46] and musical accompaniment.

Figure 7. Gerard van Honthorst: King David playing the harp

David and the Psalms. The Psalms, many of which are traditionally ascribed to David and Solomon, include some of the richest prophecies and expositions of temple themes in scripture.[47] Although we typically read them aloud today in the same fashion as we read other passages of scripture, in fact they are written as lyrics for musical performances where human and instrumental voices were to be inseparably blended, thus providing a potent echo of the divine Voice.

According to John Curtis Franklin, the Psalms offer “several striking expressions”[48] of the relationship between music and prophecy. For example, in Psalm 49, the singer discloses his “prophetic process” in saying: “I will open my dark saying [māšāl = parable] upon the harp.”[49] Franklin argues that the “I” in this and related verses refers to God, implying that the Lord Himself speaks through the voices of the singer and the lyre:

The emphasis would be less on the psalmodist using the lyre and its music to communicate with Yahweh, than on Yahweh placing his message into the lyre, from which the singer must attempt to extract it. In doing so, however, Yahweh himself becomes a kind of lyrist, so that the human lyre-prophet is attempting to replicate the song and message that God has devised for him.

This is precisely the context of prophetic passages in the Bible[50] and the Doctrine and Covenants[51] where the faithful are seen in future scenes as singing a “new song.” The emphasis on the “newness” of the song is not to signal to eager ears that tired, old songs are being put aside in favor of more refreshingly relevant ones.[52] Rather, the song is “new” because it is being newly revealed through the Spirit as it is being voiced; it is “new” because the singing is freshly spoken from the mouth of God through His servants, whether or not the words have been sung previously.[53]

Figure 8. Jonathan invests David with his princely garments and weapons

The women of Israel praise David in song. In contrast to the growing hatred and resentment of Saul, David attracts the love of the court and the nation.[54] The universal response to his exceptional qualities is symbolized by the loyalty he garners even among two key members of the royal family: Michal, Saul’s daughter, and Jonathan, Saul’s heir.

Jonathan and David go so far as to make a mutual covenant,[55] “a formal agreement of friendship and mutual loyalty.”[56] The tendency to read their friendship as homoerotic fails to recognize such pacts as a common feature in “a warrior society, in which male bonding has always been central. A further possibility is that the relationship is playing an ironic role in the text: the person about whom each cares the most is the one with whom he has the greatest potential political conflict.”[57] Reinforcing this irony is Jonathan’s conferral of garments and arms on David, a gesture emblematic of royal investiture in the ancient world.[58] Jonathan’s gifts constitute at least a symbolic, if not formal, transfer of “his claim on Saul’s throne to David.”[59]

Figure 9. Tissot: David’s return

Whereas Jonathan recognizes David’s honors as rightfully deserved, his military exploits only serve to stoke the jealousy and murderous rage of Saul.[60] Particularly galling was the praise of the women in “singing and dancing, … with tabrets, with joy, and with instruments of musick”[61] after David’s victory over the Philistines. The words of their antiphonal chorus explicitly highlighted the difference in popular perception between the increasingly unstable king and the rising young hero: “Saul hath slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands”:[62]

And Saul was very wroth, and the saying displeased him; and he said, They have ascribed unto David ten thousands, and to me they have ascribed but thousands: and what can he have more but the kingdom?

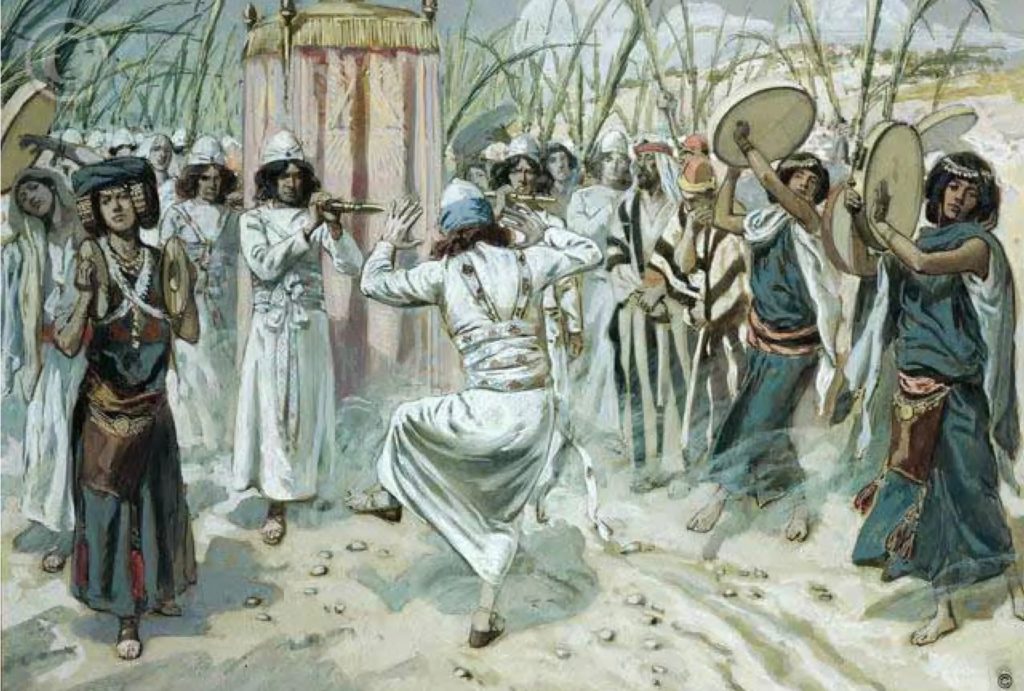

Figure 10. Tissot: David dances before the Lord

David dances before the Lord. Ironically, Saul was figuratively “among the prophets”[63] once again when he correctly predicted David’s rise and his own downfall. The praise of “all cities of Israel”[64] that were heaped upon David at this earlier incident anticipated David’s later triumphal entry into Jerusalem with the Ark of the Covenant as both a king and priest.[65] This second time the focus was not the women but rather on David himself, who danced with memorable exuberance.[66] The scriptural description — that “David danced before the Lord with all his might”[67] — epitomizes the same spirit of single-minded, wholehearted consecration to the service of God that is enjoined in Deuteronomy 6:5.[68]

Franklin correctly observes that “the massive musical procession, with its jubilant atmosphere, is clearly a sort of victory march.”[69] But, of course, the religious meaning of the event is much deeper than a mere military parade — ancient readers would have recognized the sacred ritual pattern in such events, which typically were reenacted each year in surrounding cultures:

A ceremony typical of ancient Near Eastern rituals in which the statue of the national god (to which the Ark corresponds in Israel’s aniconic religion [i.e., a religion that rejects physical representations of deity]) is introduced to a newly built or newly captured royal city. In a ceremonial march the god is borne into the city, with numerous sacrifices along the way,[70] and installed in the sanctuary,[71] followed by the distribution of food and drink to the populace.[72] … For every six paces the Ark bearers advance David sacrifices an ox and a fatling (i.e., “a fatted ox”), progressively sanctifying the City of David so that it will be ritually suitable to house the Ark.

Franklin describes the musical aspects of what he described as “the most magnificent knr [lyre] performance on record”:[73]

After David consulted with the country’s leading men, and drew up the new musical groups of string-players, cymbalists, frame-drummers, and trumpeters, “the whole people” — some seventy thousand in the LXX [i.e., the Septuagint, an ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible] — “came together as they had planned.” The expression suggests a staged crowd as much as a spontaneous popular movement. The Ark was borne out on a river of sound.

Figure 11. Tissot: Michal despises David.

The one sad down-note in the entire spectacle was the complaint of Michal, David’s wife and Saul’s daughter. Refraining from the festivities, she looked down at the ceremony from a distance through a window, highly offended. To her, David’s dancing was both indecently indecorous and personally humiliating. However, David was doing no more than what was expected and required of a king in this setting. As V. Philips Long observed:[74]

Michal’s criticism of David shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the requirements of Israelite kingship and effectively seals the fate of the house of Saul.[75] David’s humbling himself before Yahweh not only comports nicely with the consistent emphasis in 1-2 Samuel on the honor of Yahweh, but it also finds at least general analogy in Mesopotamian ritual texts. … Following his humiliation, the king is “reinvested with the symbols of office, is crowned, and is extolled with praises and wishes for a long reign.”

Probing deeper than the surface tension in the relationship between David and Michal as a couple,[76] Franklin reveals Michal’s complaint and David’s reply as a sign that the rift in the two royal families has become irreconcilable:[77]

Why does Michal react so strongly against this performance? … Clearly he is putting on a mantle of kingship, publicly demonstrating divine favor while simultaneously seeking to secure it. … The popular nature of David’s rite is clear: it is repeatedly stressed that “all the people” are present (with “every kind of local song”). In gratifying the crowd to this extent, David goes far beyond any royal display credited to Saul, and thereby shows himself to be “more kingly.”

It is therefore appropriate and revealing that it is Michal, the last vital link between David and her deposed father, who objects to these novel royal antics. David, in his rejoinder, takes up the implied contrast with Saul, and asserts that the performance is divinely-approved and his royal prerogative: “It was before the Lord, who chose me in place of your father and all his household, to appoint me as prince over Israel, the people of the Lord, that I have danced before the Lord.”[78]

The chapter closes with this terse summary of the results of the exchange between David and Michal: “Therefore Michal the daughter of Saul had no child unto the day of her death.”[79] According to P. Kyle McCarter, the principal purpose of this episode was to “explain Michal’s childlessness and to show that the blood of the house of Saul was never mixed with that of the house of David.”[80]

Figure 12. Detail from ‘Sea Peoples’ reliefs, Medinet Habu, reign of Ramses III (ca. 1184–1152 BCE)[81]

Music and the institution of kingship. In the ancient Near East, being an inspired lyrist was “considered a royal virtue.”[82] The surprising number of incidents outlined above where the presence of the lyre is assigned a prominent part in David’s ascent from shepherd boy to king demonstrate its use as “a pivotal narratological device.”[83] In addition, however, it reflects “the instrument’s more ancient potency in the royal cults of the wider region.”[84] According to Franklin, one of the themes of the book of Samuel that would have been recognized by both the Israelites and their neighbors is that “David is not merely a king who happens to play the kinnōr. He is king in large part because he plays it, incomparably well.”[85]

During the acting and regular re-enacting of ceremonies conferring divine authority and popular acclaim upon the king, music not only accompanied scenes of triumphal entry and ritual humiliation, but also the culminating rites of the transfer of power. Indeed, Franklin sees hints that the terms for “song” and “power” could be equated in certain contexts.[86]

The concept of a ritual journey that conveyed the rights of kingship were shared to a greater or lesser degree throughout the ancient Near East. John Walton observes that “the ideology of the temple is not noticeably different in Israel than it is in the ancient Near East. The difference is in the God, not in the way the temple functions in relation to the God.”[87] In addition, Nicolas Wyatt summarizes a wide range of evidence indicating “a broad continuity of culture throughout the Levant”[88] wherein the candidate for kingship underwent a ritual journey intended to confer a divine status as a son of God[89] and allowing him “ex officio, direct access to the gods. All other priests were strictly deputies.”[90]

Scholars have long debated the meaning of scattered fragments of rituals of sacral kingship in the Old Testament, especially in the Psalms, but over time have increasingly found evidence of parallels with Mesopotamian investiture traditions.[91] In this regard, one of the most significant of these is Psalm 110, an unquestionably royal and — for Christians — messianic passage:[92]

- A word of the Lord for my lord: Sit at my right hand,

till I make your enemies a stool for your feet- The Lord shall extend the sceptre of your power from Zion,

so that you rule in the midst of your enemies.- Royal grace is with you on this day of your birth,

in holy majesty from the womb of the dawn;

upon you is the dew of your new life.- The Lord has sworn and will not go back:

You are a priest forever, after the order of Melchizedek.- The Lord at your right hand

will smite down kings in the day of his wrath.- In full majesty he will judge among the nations,

smiting heads across the wide earth.- He who drinks from the brook by the way

shall therefore lift high his head.

John Eaton discusses the import of these verses and explains that they formed part of:[93]

… the ceremonies enacting the installation of the Davidic king in Jerusalem. The prophetic singer announces two oracles of the Lord for the new king (vv. 1, 4) and fills them out with less direct prophecy (vv. 2-3, 5-7). Items of enthronement ceremonial seem reflected: ascension to the throne, bestowal of the sceptre, anointing and baptism signifying new birth as the Lord’s son (v. 3[94]), appointment to royal priesthood,[95] symbolic defeat of foes, the drink of life-giving water. As [in Psalms] 2, 18, 89, [and] 101, the rites may have involved a sacred drama and been repeated in commemorations, perhaps annually in conjunction with the celebration of God’s kingship, for which the Davidic ruler was chief “servant.”

Franklin argues that parallels from similar ceremonies in the ancient Near East make the events reported in 1 Samuel “perfectly plausible as an historical event [that might] amount to, and/or [be] derived from, a descriptive ritual”[96] associated with the Jerusalem temple. He further argues, on these and other grounds, for “a near contemporary date”[97] for the composition of 1 Samuel’s account of the Davidic ritual. This would also “provide an attractive practical explanation for why the ritual actions of Solomon and Hezekiah share three structuring elements with those of David”:[98]

All three rituals include seven … song-acts governing the establishment, building, or maintenance of the cult center. The continuity between these events is made explicit. Solomon’s completion of the Temple is seen as the fruition of David’s own vision; the Levites minister “with instruments for music … that King David had made for giving thanks to the Lord.”[99] Hezekiah’s musicians were stationed, says the Chronicler, “according to the commandment of David.”[100]

Figure 13. Temple choir and orchestra

Musical management in the temple of Solomon. According to Franklin, biblical accounts of musical management in the temple of Solomon seem to have been “built upon an historical core.”[101] We quote directly from his comparative summary of the situation:

A major state needed a system for the training and management of musicians. Traditionally the sacred musical groups were inaugurated by David to accompany the Ark’s removal to Jerusalem, and were perpetuated in service before the Tabernacle at its new home. The ‘singers’ were divided into ‘families’ by specific instruments: the major groups were strings (kinnōr, nēbel), cymbals (m ṣiltayīm), and trumpets (shofar).[102] …

Here I would emphasize that the … make-up [of the musical ensemble of prophets that Saul met at Gibeath-elohim — nēbel, frame-drum (tof), pipes (ḥalil), and kinnor —] is not dissimilar to what David’s musical “families” will offer, and which one must posit for [Israel’s neighbors at] Ugarit. This array has been called a “[Syro-Levantine] (temple) orchestra.” …

David’s full musical establishment is said to have been under the management of a certain Chenaniah who “was to direct the music, for he understood it.”[103] The exact interpretation of his position vis-à-vis the Levitical guilds remains controversial; but some definite musical function is likely given the Septuagint’s [designation of him as] “Leader of the Singers.” While it is elsewhere stated that he and his sons were “officials and judges” outside the Temple, this actually resembles the Chief Singer of such Old Babylonian states as Mari, whose duties were not exclusively musical, but comprised important civic functions. David himself, in the court of Saul (ca. 1025–1005), had occupied a comparable position. There was not yet an elaborate musical bureaucracy for him to preside over, but he was evidently a royal singer and confidant of the king — at least initially. …

David was also remembered as building instruments and instructing the Levites in their use. One recalls the royal order for instruments, including the kinnāru, at Mari. Solomon too is called an instrument-builder. Josephus preserves an extra-Biblical tradition in his vivid portrait of forty thousand lyres (knr and nbl) made of precious woods, stones, and electrum, commissioned for the Levites to sing the Lord’s praises. … There is plenty of comparative material to show that the musical organization credited to the First Temple by tradition is inherently plausible, even if the precise numbers and divisions are open to question. Given the royal ambitions of David and Solomon, it is hard to believe that Yahweh would have lacked the sophisticated honors paid to Baal and other gods in the temples of their peers.

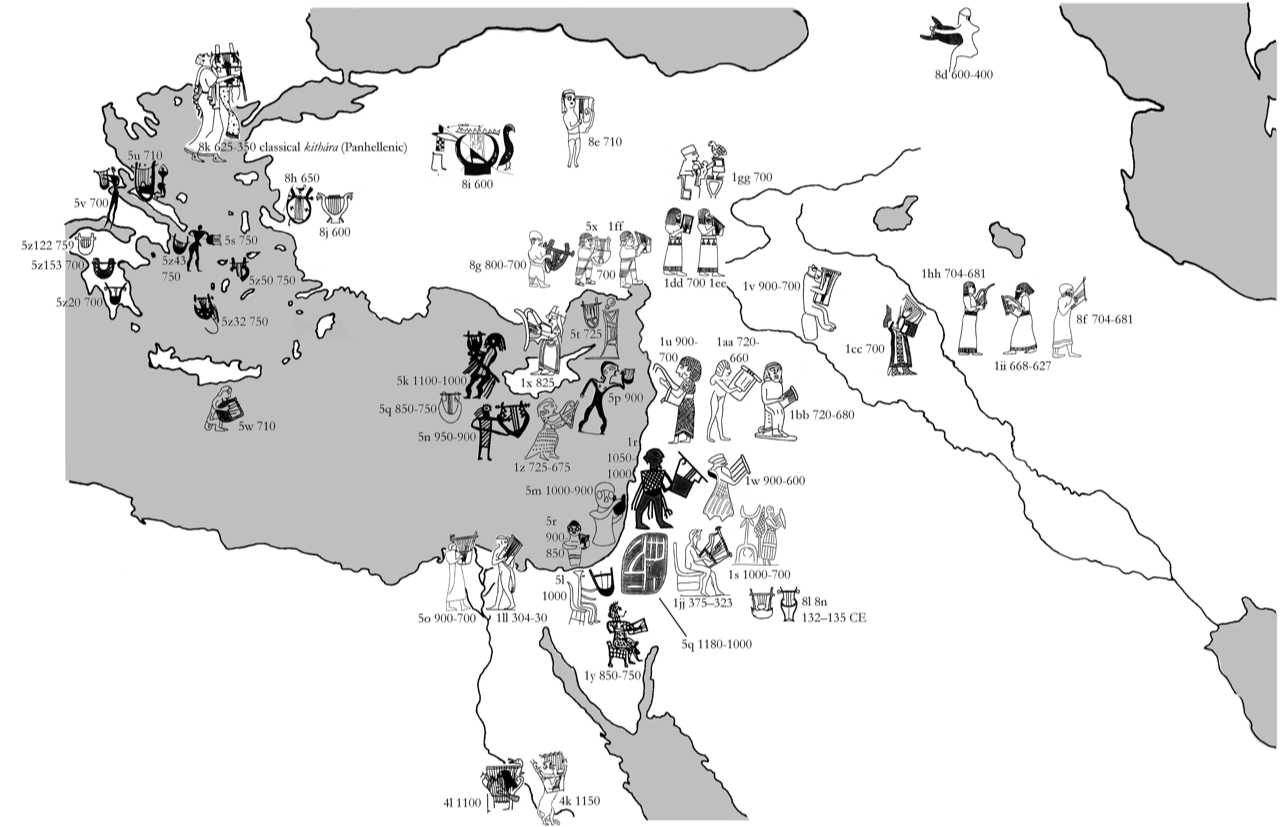

Figure 14. Distribution of Iron Age Lyres in the ancient Near East>[104]

The Why

Some modern musicologists and instrument makers have tried to re-create David’s lyre. They have taken their inspiration about its shape from a variety of sources, including a stone-age wall carving of a female lyre-player found at Megiddo,[105] a seventh-century seal depicting a lyre,[106] and even the shape of the Sea of Galilee — sometimes known in the Bible as “Chinnereth.”[107] They have varied the number of strings from a small number up to twenty-two. This latter configuration allows each letter of the Hebrew alphabet to be represented musically, permitting exceptionally perceptive listeners to discern words in the notes of the music as it is played.

However, readers should be wary of the overconfident claims by some of the “return of David’s harp”[108] in these re-creations. It is highly doubtful that the shape, string configuration, and tuning of David’s lyre will ever be determined definitively. For one thing, there is a rich variety of ancient prototypes produced through continuing innovation from the Bronze Age onward. For another thing, since Davidic lyres were part of the furniture of the First Temple it seems that they were subject to the same sort of prohibitions on artistic representation that limits our understanding of the appearance of similar sacred artifacts from that time period.

That said, it should not be forgotten that the spiritual power of David’s music was not due to the particular characteristics of his instrument or his talents as a singer and player, but rather to the fact that “the Lord was with him.”[109]

Fortunately, such musicians still bless the lives of the Saints in modern times. William Pitt’s Brass Band lifted spirits in Nauvoo and on the pioneer trail, and later performed at the laying of the cornerstone for the Salt Lake Temple.[110] The Mormon Tabernacle Choir was formed soon after the Saints entered the Valley and, frequently accompanied by the Orchestra at Temple Square, performs in significant musical events around the world, both secular and sacred.[111] At the recent celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the revelation on the priesthood, church members thrilled to the sound and spirit of Gladys Knight’s “Be One Choir.”[112]

On the local level, the Church continues to encourage the learning and playing of piano and organ music both in areas with long-established congregations as well as in places where the faith is newly emerging. “State officials … brag about Utah’s top standing in a statistical category so obscure that other states somehow fail to mention it: Pianos per capita,” making the area what the Los Angeles Times called “a piano peddler paradise.”[113] When missionary work began in Africa, the Church organized a corps of piano teachers to follow in the footsteps of the missionaries, while simultaneously seeking to embrace local musical traditions in a sensitive and appropriate manner.[114]

Figure 16. Tamara Oswald

The most well-known harp player among the Latter-day Saints today is Tamara Oswald, who is the principal harp with the Orchestra at Temple Square. In partnership with Jeannine Goeckeritz, principal flute with the Orchestra, she performs widely as part of the Oswald Goeckeritz Duo.[115]

Playing a modern harp is an incredibly challenging mental and physical task that requires both extreme forms of daily diligence and years of experience. Just tuning the instrument’s many strings, let alone playing them, is a labor of love. One of many demonstrations that “the Lord [is] with [Tamara]”[116] occurred a few years ago, as was reported by local news outlets:[117]

The beautiful sound of the harp orchestrates Tamara Oswald’s life, but the music abruptly faded on January 8th while she was getting ready to go to a concert.

“From one second to the next my vision just went wacko, double vision, blurry vision and everything was askew,” said … Tamara Oswald. “Then I started to get dizzy and lightheaded.”

Tamara was having a massive stroke, but she didn’t know it. So she laid down on the floor and took a nap for about an hour. As Tamara faded out of consciousness, she says the first miracle happened. Her husband as her guardian angel felt the need to go home for lunch.

“He found me. I was paralyzed at that point on the entire left side and I couldn’t speak well,” said Oswald.

Tamara was rushed to the Emergency Department at Intermountain Medical Center where the stroke team guided her through recovery. … She failed every stroke test: seeing, smiling, lifting her arm, and walking. …

[However,] “By the time they finished infusing [TPA, a stroke-treatment], I started gaining mobility in my left side,” said Oswald.

Tamara stayed in the hospital for 48 hours. Within a week, she was almost back to normal and practicing her passion.

“I was doing another school concert within that week. I was teaching lessons again,” said Oswald.

Due to the spiritual prompting of her husband, masterful medical care, the many prayers of family and friends, and the resumption of a strenuous practice and performance regime, the miracle of music — a divine gift prized since ancient times — was restored to Tamara and all the rest of us have been blessed as a result.

My gratitude for the love, support, and advice of Kathleen M. Bradshaw on this article. Thanks also to Jonathon Riley and Stephen T. Whitlock for valuable comments and suggestions.

Further Study

For a comprehensive study of the religious role of the lyre in the ancient world, see J. C. Franklin, Kinyras. For specific details on archaeological findings relating to music in ancient Israel, see J. Braun, Music in Ancient Israel

See N. M. Weinberger, Music and the Brain for a broad, though somewhat dated, overview of the cognitive and affective dimensions of music. For a limited study that signals the need for caution in making claims that the specific skills gained through musical education generalize to wider cognitive abilities, see S. A. Mehr, et al., Two Randomized Trials.

For a sampling of the music of Jeannine Goeckeritz and Tamara Oswald, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H0YRDjPjX_w (accessed June 2, 2018).

For other scripture resources relating to this lesson, see The Interpreter Foundation Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Index (https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/gospel-doctrine-resource-index/ot-gospel-doctrine-resource-index/) and the Book of Mormon Central Old Testament KnoWhy list (https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/tags/old-testament).

References

al-Kisa’i, Muhammad ibn Abd Allah. ca. 1000-1100. Tales of the Prophets (Qisas al-anbiya). Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, Jr. Great Books of the Islamic World, ed. Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Chicago, IL: KAZI Publications, 1997.

Alter, Robert, ed. The David Story: A Translation with Commentary of 1 and 2 Samuel. New York City, NY: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Attridge, Harold W., Wayne A. Meeks, Jouette M. Bassler, Werner E. Lemke, Susan Niditch, and Eileen M. Schuller, eds. The HarperCollins Study Bible, Fully Revised and Updated Revised ed. New York City, NY: HarperOne, 2006.

Baker, LeGrand L., and Stephen D. Ricks. Who Shall Ascend into the Hill of the Lord? The Psalms in Israel’s Temple Worship in the Old Testament and in the Book of Mormon. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2009.

Barker, Margaret. "Who was Melchizedek and who was his God?" Presented at the 2007 Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Session S19-72 on ‘Latter-day Saints and the Bible’, San Diego, CA, November 17-20, 2007.

———. Christmas: The Original Story. London, England: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 2008.

———. 2016. The Lord Is One. Public speech presented at the Varsity Theatre, at BYU, in Provo, Utah, November 9, 2016, co-sponsoted by BYU Studies, the Academy for Temple Studies, and The Interpreter Foundation. In YouTube Mormon Interpreter Channel.

Barrett, William. The Illusion of Technique: A Search for Meaning in a Technological Civilization. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1978.

Berlin, Adele, and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds. The Jewish Study Bible, Featuring the Jewish Publication Society TANAKH Translation. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Ancient and Modern Perspectives on the Book of Moses. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2010.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Publishing, 2012.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Ronan J. Head. "The investiture panel at Mari and rituals of divine kingship in the ancient Near East." Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 4 (2012): 1-42.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M. Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve. 2014 Updated ed. In God’s Image and Likeness 1. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. Temple Themes in the Oath and Covenant of the Priesthood. 2014 update ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014.

———. "’He that thrusteth in his sickle with his might … bringeth salvation to his soul’: Doctrine and Covenants section 4 and the reward of consecrated service." In D&C 4: A Lifetime of Study in Discipleship, edited by Nick Galieti, 161-278. Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2016.

———. "What did Joseph Smith know about modern temple ordinances by 1836?”." In The Temple: Ancient and Restored. Proceedings of the 2014 Temple on Mount Zion Symposium, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Donald W. Parry. Temple on Mount Zion 3, 1-144. Orem and Salt Lake City, UT: The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2016.

Bradshaw, Jeffrey M., and Matthew L. Bowen. "”By the Blood Ye Are Sanctified”: The Symbolic, Salvific, Interrelated, Additive, Retrospective, and Anticipatory Nature of the Ordinances of Spiritual Rebirth in John 3 and Moses 6." Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 24 (2017): 123-316. https://journal.interpreterfoundation.org/by-the-blood-ye-are-sanctified-the-symbolic-salvific-interrelated-additive-retrospective-and-anticipatory-nature-of-the-ordinances-of-spiritual-rebirth-in-john-3-and-moses-6/. (accessed January 10, 2018).

Braun, Joachim. Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine: Archaeological, Written and Comparative Sources. Translated by Douglas W. Stott. The Bible in its World. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2002.

Cohen, Susan. "Interpretive Uses and Abuses of the Beni Hasan Tomb Painting." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 74, no. 1 (2015): 19-38.

Crow, Nadia. 2015. Time is crucial in stroke treatment. In Good4Utah.com. http://www.good4utah.com/good4utah/time-is-crucial-in-stroke-treatment/163129200 2/. (accessed June 2, 2018).

Dennis, Lane T., Wayne Grudem, J. I. Packer, C. John Collins, Thomas R. Schreiner, and Justin Taylor. English Standard Version (ESV) Study Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2008.

Dunn, James D. G., and John W. Rogerson. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2003.

Eaton, John H. Kingship and the Psalms. London, England: SCM Press, 1976.

———. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. London, England: T&T Clark, 2003.

Fox, Everett. The Early Prophets: Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. The Schocken Bible 2. New York City, New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2014.

Franklin, John Curtis. Kinyras: The Divine Lyre. Hellenic Studies Series 70. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2016. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_FranklinJ.Kinyras.2016. (accessed May 29, 2018).

Gileadi, Avraham. "The twelve diatribes of modern Israel." In By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks. 2 vols. Vol. 2, 353-405. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990.

Harrington, D. J. "Pseudo-Philo." In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by James H. Charlesworth. 2 vols. Vol. 2, 297-377. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1983.

Hocart, A. M. Kingship. London, England: Humphrey Milford, 1927.

Hooke, Samuel Henry. Myth, Ritual, and Kingship. Oxford, England: The Clarendon Press, 1958.

Horne, Dennis B. Bruce R. McConkie: Highlights from His Life and Teachings. Roy, UT: Eborn Books, 2000.

Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985.

James, E. O. "Initiatory rituals." In Myth and Ritual, edited by Samuel Henry Hooke, 147-71. London, England: Oxford University Press, 1933.

Jamieson, Robert, Andrew Robert Fausset, and David Brown. 1871. A Commentary Critical and Explanatory on the Whole Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1967.

Johnson, Aubrey R. Sacral Kingship in Ancient Israel. Cardiff, Wales: University of Wales Press, 1955. Reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2006.

L’Orange, H. P. Studies on the Iconography of Cosmic Kingship in the Ancient World. New Rochelle, NY: Caratzas Brothers and Instituttet for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning, 1982.

Larsen, David J. "The Royal Psalms in the Dead Sea Scrolls." Doctoral Dissertation, St. Andrews University, 2013.

Long, V. Philips. "1 Samuel." In Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 & 2 Samuel, edited by John H. Walton. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary 2. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

McConkie, Bruce R. A New Witness for the Articles of Faith. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1985.

———. Doctrines of the Restoration: Sermons and Writings of Bruce R. McConkie. Salt Lake City, UT: Bookcraft, 1989.

Mehr, Samuel A., Adena Schachner, Rachel C. Katz, and Elizabeth S. Spelke. 2013. Two randomized trials provide no consistent evidence for nonmusical cognitive benefits of brief preschool music enrichmnet. In PLOS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082007. (accessed June 11, 2018).

Mowinckel, Sigmund. 1962. The Psalms in Israel’s Worship. 2 vols. The Biblical Resource Series, ed. Astrid B. Beck and David Noel Freedman. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004.

Murphy, Frederick J. Pseudo-Philo: Rewriting the Bible. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Nibley, Hugh W. 1975. The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment. 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2005.

———. 1986. Teachings of the Pearl of Great Price. Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Brigham Young University, 2004.

Palmer, Spencer J. "Mormons in West Africa: New Terrain for the Sesquicentennial Church (27 September 1979)." Presented at the BYU Annual Religion Faculty Lecture (Church History Library, Call Number M276.6 P176m 1979), Provo, Utah 1979.

Postgate, J. N. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London, England: Routledge, 1992.

Purdy, William E. "They marched their way west: The Nauvoo Brass Band." Ensign 10, July 1980, 20-23. https://churchofjesuschrist.org/ensign/1980/07/they-marched-their-way-west-the-nauvoo-brass-band?lang=eng. (accessed June 12, 2018).

Rashi. c. 1105. The Torah with Rashi’s Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Vol. 1: Beresheis/Genesis. Translated by Rabbi Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg. ArtScroll Series, Sapirstein Edition. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications, 1995.

Ricks, Stephen D. "The coronation of kings." In Reexamining the Book of Mormon, edited by John W. Welch, 124-26. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1992.

———. "Kingship, coronation, and covenant in Mosiah 1-6." In King Benjamin’s Speech: ‘That Ye May Learn Wisdom’, edited by John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks, 233-75. Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998.

Roberts, J. J. M. "Mowinckel’s enthronement festival: A review." In The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception (Formation and Interpretation of Old Testament Literature 4, Craig A. Evans and Peter W. Flint, eds.), edited by Peter W. Flint and Patrick D. Miller, Jr. Supplements to Vetus Testamentum 99, eds. H. M. Barstad, Phyllis A. Bird, R. P. Gordon, A. Hurvitz, A. van der Kooij, A. Lemaire, R. Smend, J Trebolle Barrera, James C. VanderKam and H. G. M. Williamson, 97-115. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2005.

Robinson, Edward. A Dictionary of the Holy Bible for General Use in the Study of the Scriptures with Engravings, Maps, and Tables. New York City, NY: The American Tract Society, 1859. http://books.google.com/books/about/A_Dictionary_of_the_Holy_Bible.html?id=fMgRAAAAYAAJ. (accessed July 28, 2012).

Sailhamer, John H. "Genesis." In The Expositor’s Bible Commentary, edited by Frank E. Gaebelein, 1-284. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1990.

Smith, Hyrum M., and Janne M. Sjodahl. 1916. Doctrine and Covenants Commentary. Revised ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1979.

Stone, Michael E., ed. Armenian Apocrypha Relating to Adam and Eve. Studia in Veteris Testamenti Pseudepigrapha, ed. A.-M. Denis, M. de Jonge, M. A. Knibb, H.-J. de Jonge, J.-Cl. Haelewyck and Johannes Tromp. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1996.

———. "The Sethites and the Cainites." In Armenian Apocrypha Relating to Adam and Eve, edited by Michael E. Stone, 201-06. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, 1996.

Tsumura, David Toshio. The First Book of Samuel. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament, ed. Robert L. Hubbard, Jr. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2007.

Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006.

Weinberger, Norman M. 2006. Music and the brain. In Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/music-and-the-brain-2006-09/ 1/. (accessed June 2, 2018).

"What did David’s lyre look like? A delicate jasper seal may tell us." Biblical Archaeology Review 8, no. 1 (1982). https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/8/1/3. (accessed June 11, 2018).

Widengren, Geo. The King and the Tree of Life in Ancient Near Eastern Religion. King and Saviour IV, ed. Geo Widengren. Uppsala, Sweden: Almquist and Wiksells, 1951.

———. "King and covenant." Journal of Semitic Studies 2, no. 1 (1957): 1-32.

Wyatt, Nicholas. "Kinnaru." In Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking and Pieter W. van der Horst, 488. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1999.

Wyatt, Nicolas. Myths of Power: A Study of Royal Myth and Ideology in Ugaritic and Biblical Tradition. Ugaritisch-Biblische Literatur 13. Münster, Germany: Ugarit-Verlag, 1996.

———. "Degrees of divinity: Some mythical and ritual aspects of West Semitic kingship." In ‘There’s Such Divinity Doth Hedge a King’: Selected Essays of Nicolas Wyatt on Royal Ideology in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature, edited by Nicolas Wyatt. Society for Old Testament Study Monographs, ed. Margaret Barker, 191-220. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2005.

———. ‘There’s Such Divinity Doth Hedge a King’: Selected Essays of Nicolas Wyatt on Royal Ideology in Ugaritic and Old Testament Literature. Society for Old Testament Study Monographs, ed. Margaret Barker. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2005.

Endnotes

In most cases where the lyre is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible it is simply a matter of the use of the instrument in popular (Job 21: 12) or cultic (2 Sam 6:5) context, often in association with other instruments. In no instance can it be understood as a divine name as in Ugaritic, but the following passages may faintly echo the old theology, albeit long reinterpreted [e.g., Psalm 49:5; 57:9 = 108:3. These passages echo] an older usage when minor gods of the pantheon were called upon to glorify their overlord.”

The gift of the divine spirit, next noted (1 Samuel 16:13b), associates David with both Samson and Saul but also distinguishes him from both. Reports of the spirit empowering or taking over Samson and Saul appear as short-term responses to a particular stimulus, whether of danger (Judges 14:6, 19; 15:14), anger (1 Samuel 11:6), or contagious behavior (1 Samuel 10:6, 10). Here the divine spirit accompanies the anointing and continues with David “from that day forward.” The consequence for Saul is carefully stated in the next verse: the spirit of Yahweh leaves him (it cannot be divided?), and an evil spirit from Yahweh afflicts him.

In 1 Samuel 19:24, we are told that Saul, like the other prophets that were with him, “stripped off his clothes also, and prophesied, … and lay down naked all that day and all that night.” Jamieson clarifies that “lay down naked” in this instance meant only that he was “divested of his armor and outer robes” (R. Jamieson et al., Commentary, pp. 219-220 n. 24. Cf. D. T. Tsumura, 1 Samuel, p. 499). In a similar sense, when we read in John 21:7 that Peter “was naked” as he was fishing, it simply meant that “he had laid off his outer garment, and had on only his inner garment or tunic” (E. Robinson, Dictionary, p. 302 s.v., Naked).

Much mystery surrounds the specific connotations of the rather extensive vocabulary of music in the Bible, but Israel’s stock of musical instruments included stringed, percussion, and wind instruments, such as were known among Israel’s ancient Near Eastern neighbors generally. …

The “flute” was likely a “double pipe,” such as is illustrated by a terra cotta figurine discovered at Tel Malḫata. The “tambourine” was a “small, shallow, handheld frame drum,” stretched with animal skin and played with the hand. The metal disks of modern tambourines were almost certainly absent. Archaeologists in Mesopotamia and the Levant have discovered numerous female figurines holding disk-like objects that, according to the detailed studies of Carol Meyers, represent tambourines. …

The word rendered “harp” in the NIV (kinnôr) probably refers to a “lyre,” of which there were several types in antiquity. (Conversely, the term that the NIV renders “lyre” [nēbel] probably refers to a “harp.”) The type of lyre David played was presumably the “Eastern,” or “thin,” lyre, which was strung with four to eight strings and was played with a plectrum. The “thick” lyre had ten to thirteen strings and was played with the fingers. No evidence of thick lyres has been discovered in Palestine. …

Lyres were constructed using “a rectangular sound-box, two asymmetrical arms, and an oblique yoke,” with strings stretched between the sound-box and the yoke.

Archaeological discovery has yielded many representations of lyres, such as the remains of nine lyres from the Sumerian royal cemetery at Ur (ca. 2500 BCE), a depiction of “an Amorite/Canaanite lyre player entering Egypt with his clan” (ca. 1900 BCE wall painting at Beni Hasan in Egypt), a depiction of a female lyre player on an ivory plaque from Megiddo (twelfth century BCE), and a male lyre player on a Philistine bichrome jug (Megiddo, eleventh century BCE).

Some have suggested that music may have induced a kind of prophetic ecstasy, such as is attested among Mari prophets. The Bible does attest to a role for music in inducing prophetic receptivity (2 Kings 3:15–16), but in contexts where prophecy devolves into erratic behavior the focus tends not to be on true worshipers of Yahweh but on those at odds with him (e.g., Saul in 1 Sam. 18:10; the prophets of Baal in 1 Kings 18:29). Biblical prophets are occasionally referred to as “madmen” (2 Kings 9:11; Jeremiah 29:26; Hosea 9:7), though never by the authoritative narrator with respect to true prophets of Yahweh.

The holy anointing oil was used only in the temple. Any imitation for personal use was forbidden (Exodus 30:31–33). The meaning of the oil was found only within the teachings of the temple, and any secular use would make no sense. This was because the oil imparted knowledge. The temple understanding of holiness included illumination of the mind. Isaiah said that when the king was anointed, he received the spirit of the Lord, that is, the spirit that transformed him into the Lord. He received the spirit [that is, the angel] of wisdom, of understanding, of counsel, of might, of knowledge and of the reverence due to the Lord [“the fear of the Lord”]. His perfume [not “delight”] would be the reverence due to the Lord (Isaiah 11:2–3). In other words, the anointed one retained the perfume of the oil, and this identified him as the Lord. Paul said that Christians were spreading the perfume of the knowledge of the Anointed One, which did not mean knowing about Jesus; it meant having the knowledge that Jesus had because He was the Anointed One (2 Corinthians 2:14).

David is referred to as “the sweet psalmist of Israel” (2 Samuel 23:1) and as the author of several songs (2 Samuel 1:17–27; 22:1–51; 1 Chronicles 16:7–36; see also Amos 6:5) and many psalms. He is also credited with establishing the temple musicians (1 Chronicles 6:31). The music that David habitually played in Saul’s presence was not merely beautiful, but music of worship to the Lord, causing Saul to be refreshed and the harmful spirit to flee (cf. 2 Chronicles 5:13–14).

More generally, Elder Hyrum M. Smith and Janne M. Sjodahl explained ” (H. M. Smith et al., Commentary, p. 350):

When the Spirit of the Lord speaks through a human instrument, He acts independently, even when proclaiming truths formerly revealed. Strictly speaking, the Holy Spirit does not quote the Scriptures, but gives Scripture.

Elder Bruce R. McConkie once expressed a similar point (D. B. Horne, McConkie, p. 205; B. R. McConkie, New Witness, p. xii):

In speaking of these wondrous things I shall use my own words, though you may think they are the words of scripture, words spoken by other apostles and prophets. True it is, they were first proclaimed by others, but they are now mine, for the Holy Spirit of God has borne witness to me that they are true, and it is now as though the Lord had revealed them to me in the first instance. I have thereby heard his voice and know his word.

On another occasion Elder McConkie said (D. B. Horne, McConkie, p. 205; B. R. McConkie, Sermons, p. 256):

If the Spirit bears record to us of the truth of the scriptures, then we are receiving the doctrines in them as though they had come to us directly. Thus, we can testify that we have heard his voice and know his words.

Hence, just as scripture constitutes a report of an encounter with God’s voice, an authentic experience with scripture invites God’s presence anew, with the possibility of further revelation (see, e.g., Joseph Smith—History 1:11ff.; D&C 76:15-19, 138:1-11).

The verb [used here to describe Saul’s wrath] is the same one that refers to “speaking in ecstasy” or “prophesying” in the episode of Saul among the prophets, but in the present context only the connotation of raving and not that of revelation is relevant. when David was playing as he was wont to. … In the Hebrew, “was playing” [in verse 10] is literally “was playing with his hand,” which sets up a neat antithesis to the spear in Saul’s hand (“with” and “in” are represented by the same particle, be in Hebrew).

It is a fixed rule in biblical poetry that when a number occurs in the first verset, it must be increased in the parallel verset, often, as here, by going up one decimal place. Saul shows himself a good reader of biblical poetry: he understands perfectly well that the convention is a vehicle of meaning, and that the intensification or magnification characteristic of the second verset is used to set David’s triumphs above his own. Saul, who earlier had made the mistake of listening to the voice of the people, now is enraged by the people’s words.

The wearing of the ephod surely underscores the fact that in the procession of the Ark into Jerusalem David is playing the roles of both priest and king — a double service not unknown in the ancient Near East (compare Melchizedek in Genesis 14).

Scrutiny of the words used to describe David’s dancing suggests that it is an exuberant, energetic leaping and whirling about.

While ancient Near Eastern literature provides no other examples of kings dancing in such processions, instances of the queen joining in a ritual dance, followed by other dignitaries, are known from Hittite sources. Depictions of dancers in a broad range of ancient Near Eastern pictorial sources give some sense of what this dancing may have been like. Dancing was done either in groups or singly and was often quite acrobatic. Dancing took place in a variety of settings and for a variety of reasons, as it has in most cultures up to the present time. It could be a spontaneous expression of joy and playfulness; on occasion it could verge into eroticism; and it was often a component of cultic ceremonies.

Dancing was not always evaluated positively. An Akkadian letter from the first half of the second millennium criticizes a woman who had “greatly aggravated the matter.” The letter explains: “In addition to dancing about every day, she has slighted us by consistently behaving thoughtlessly.” Mostly, though, dancing was deemed a reflex of joy and well-being. A letter to the Assyrian king Assurbanipal lauds his reign as a golden age:

A good reign, righteous days, years of justice, plentiful rains, enormous floods, a good market price! The gods are appeased, there is much reverence of god, the temples abound; the great gods of heaven and earth have been exalted in the time of the king, my lord! The old men dance, the young men sing, the women and the girls are merry and happy; women are married and provided with rings, boys and girls are brought forth, the births thrive!

David’s whirling dance apparently combines personal exuberance with cultic performance.

The ephod [worn by David] was probably a short garment tied around the hips or waist, and so David whirling and leaping might easily have exposed himself, as Michal will bitterly observe. … The preceding verse reports the shouts of jubilation and the shrill blasts of the ram’s horn: first she hears the procession approaching from the distance, then she looks out and sees David dancing. Strategically, her repeated epithet in this episode of final estrangement is “daughter of Saul,” not “wife of David,” and the figure she sees is not “David her husband” but “King David.” Shimon Bar-Efrat neatly observes that at the beginning of their story a loving Michal helped David escape “through the window” from her father’s henchmen while now she looks at him from a distance “through the window,” in seething contempt. …

[Michal’s first words to David are uttered in angry sarcasm:] “How honored today is the king of Israel.” Astoundingly, until this climactic moment, there has been no dialogue between Michal and David — only her urgent instructions for him to flee in 1 Samuel 19 and his silent flight. We can only guess what she may have felt all those years he was away from her, acquiring power and wives, or during the civil war with her father’s family. We are equally ignorant of her feelings toward her devoted second husband, Paltiel son of Laish. …

Her first significant word “honored” (balanced in David’s rejoinder by two antonyms, “dishonored” and “debased”) is a complex satellite to the story of the grand entry of the Ark with which it is linked. When the Ark was lost to the Philistines (1 Samuel 4), the great cry was that “glory [or, honor, kavod — the same verbal root Michal uses here] was exiled from Israel.” Now glory/honor splendidly returns to Israel, but the actual invocation of the term is a sarcastic one, bitterly directed at David, who will then hurl back two antonyms and try to redefine both honor and dishonor to his wife. …

One should also note here that Michal speaks to her husband in the third person, not deferentially but angrily, and refers to him by public title, not in any personal relation to her. who has exposed himself today to the eyes of his servants’ slave-girls. … The social thrust of the comparison is evident: she is a king’s daughter, whereas he has now demonstrated that he is no more than riffraff.

The Ugaritic word n’m, which [was] applied … to royal and/or cultic singers, reappears of David himself — an appropriate designation both for Saul’s lyre-playing favorite, and David’s later role, when king, of praise-singer for Yahweh himself. …

It remains worth considering whether Hebrew zmr was once capable of some semantic ambivalence between ‘song’ and ‘power’ — not by virtue of historical linguistics, but ritual-poetic convention. We have seen this precise duality in the Ugaritian text RS 24.252 with its crucial wordplay on zmr/ḏmr, whereby the ‘song’ of Rāp’iu was simultaneously a source of the king’s ‘power’. The phrase nĕʿîm zimrat yiśrā’ēl may therefore imply not only that David was the Gracious Minstrel of the Might of Israel, but that his own power as Yahweh’s terrestrial agent derived precisely from his praising of Yahweh in song.

A ruler’s claim to divinity can be expressed in three ways: his name may be preceded by the cuneiform sign for god, in the same way as other deities’ names are, his headdress may be represented with horns, the mark of a god in the iconography, and in a variety of ways evidence may be seen that he was worshipped by the population in a cult of his own.… Another, attractive, hypothesis is that any rulers who were offspring of a sacred marriage could legitimately claim both divine and royal parentage. Gudea, for instance, says that he had no mother and no father and was the son of the goddess of Lagas, Garumdug; however, elsewhere he also states that he is the son of Ninsun, of Bau and of Nanse, which makes it hard to be sure of the implications of such statements. He, however, did not lay claim to divinity.

The seeming contradiction in Gudea’s claimed parentage might be explained by analogy to JST Hebrews 7:3 (“which order was without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life”), where the parallel sense is that although Melchizedek certainly had been born to earthly parents, he later had been reborn as a “Son of God” through priesthood ordinances (see J. M. Bradshaw, Temple Themes in the Oath, pp. 53-54, 60-62, 169-170 nn. 313-314).

While many of the specific criticisms of research in this tradition are well deserved, no better explanation yet has been attempted for the evidence as a whole. For example, having reviewed nearly a century of criticisms relating to Mowinckel’s theory of an Israelite enthronement festival, Roberts finds that a modified version of this idea still offers “the most adequate interpretive context for understanding both the classical enthronement Psalms and a large number of other Psalms” (J. J. M. Roberts, Mowinckel’s Enthronement Festival, pp. 113-114). Likewise, Wyatt insightfully critiques the earlier literature on this topic, but ends up making a strong case for the continuity of divine kingship traditions throughout the ancient Near East (N. Wyatt, Myths of Power; N. Wyatt, There’s Such Divinity).

LeGrand L. Baker and Stephen D. Ricks have studied temple and coronation themes in the Psalms from an LDS perspective (L. L. Baker et al., Who Shall Ascend). See other studies by Ricks for overviews of coronation themes in the Book of Mormon (S. D. Ricks, Coronation; S. D. Ricks, Kingship). For a description of similar themes in the Qumran literature, see D. J. Larsen, Themes of the Royal Cult..

He will be priest-king, the supreme figure for whom all the other personnel of the temple were only assistants. It was a role of the highest significance in the ancient societies, treasured by the great kings of Egypt and Mesopotamia under their respective deities. There are indications in the historical sources that the role was indeed held by David and his successors, though opposed and obscured in the records by priestly clans after the end of the monarchy. The oracle gives a special aspect to the priesthood by linking it to the pre-Israelite king of Jerusalem, Melchizedek. David’s dynasty are here recognized as heirs of Melchizedek, who was remembered in tradition as priest and king of El Elyon, God Most High, Creator of heaven and earth (Genesis 14:18f.). As Israel’s God took the title of the Creator as worshipped in old Jerusalem (El Elyon), so David took over the city-kingdom and royal priesthood of the old dynasty.

The importance of the kinnōr in early Jewish tradition, and royal ideology specifically, is most fully embodied by David. The Bible and Josephus offer detailed descriptions of musical organization under David (ca. 1005–965) and Solomon (ca. 965–930). Some consider these to be retrojections of the Second Temple’s sophisticated musical arrangements back into an imagined Golden Age of the First Temple. Certainly 1 Kings, Chronicles, and Josephus incorporate legendary details, and the Chronicler does rely on the musical organization of his own time to understand the past. Yet the comparative material so far considered strongly suggests that traditions about organized ‘guildic’ music under David and in the First Temple are built upon an historical core. This would accord with much other material in the books of Samuel and 1 Kings, deriving from sources and traditions — often propagandistic — going back to the times of David and Solomon themselves.

Recall the designation of Ugaritian guilds, including perhaps the singers, as bn (‘sons of’), and the Bible’s representation of Jubal as an ultimate musical ancestor of lyre- and pipes-players. The Bible’s implication of existing musical resources on which David could draw is corroborated by the extensive parallelism of the earliest specimens of Hebrew poetry, clearly akin to Ugaritian practice. Such songs are evidently relics of an ancient epic cycle, cultivated at various league sanctuaries. Some form of ‘family’ musical groups may already have served such sacred sites, and were simply repurposed by David. At such an early date, however, there is no reliable means of distinguishing “Israelite” music from a Canaanite “background.” And with Solomon’s monumental new temple, it is not improbable that the music of Yahweh’s cult would have been ‘renovated’ in conformity with standards and practices of major Canaanite sanctuaries.

Reporting on Mark’s presentation as part of a BYU History Week panel on “Mormonism in Black Africa”, the BYU Daily Universe reported: “It is hard for Africans to leave their age-old practices of their traditional religious teachings to become members of the LDS Church, said Mark Bradshaw… [The] African people like to bring their drums to church and dance and sing, because that is their tradition. ‘They have no musical instruments other than drums,’ Bradshaw said. ‘When they are not allowed to use their drums, sing their songs or clap, we deny them their culture. … We shouldn’t throw out their culture, … but it is difficult to separate their culture … and the essence of the gospel. They do have a religious quality in their singing and worshipping,’ Bradshaw said.” (26 March 1982, p. 10).