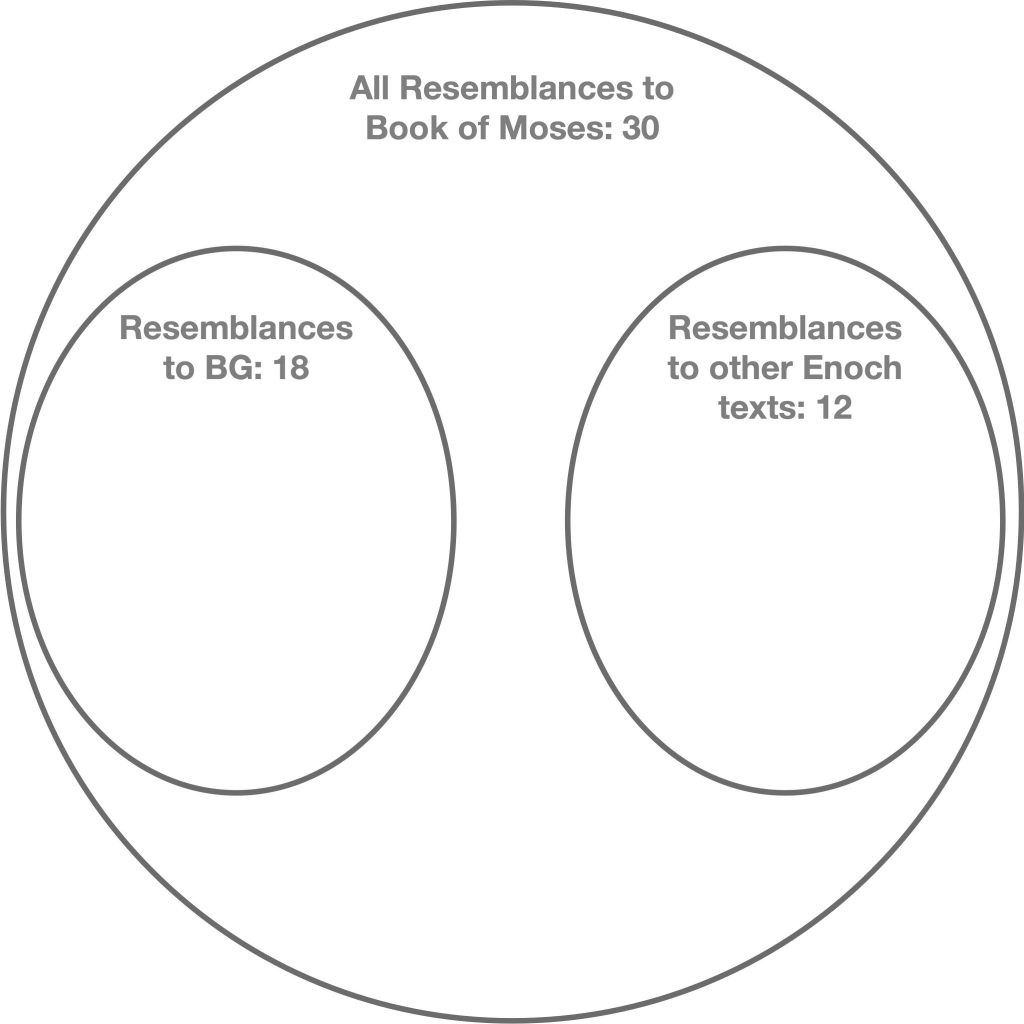

Abstract: The Book of Giants (BG), an Enoch text found in 1948 among the Dead Sea Scrolls, includes a priceless trove of stories about the ancient prophet and his contemporaries, including unique elements relevant to the Book of Moses Enoch account. Hugh Nibley was the first to discover in the BG a rare personal name that corresponds to the only named character in the Book of Moses besides Enoch himself, a finding that some non-Latter-day Saint Enoch scholars considered significant. Since Nibley’s passing, the growth of new scholarship on ancient Enoch texts has continued unabated. While Nibley’s pioneering research compared the names and roles of one character in Moses 6–7 and BG, scholars have now been able to examine the names and roles of nearly all of the prominent figures in the two books and analyze their respective accounts in more detail. Not only are the overall storylines of the two independent accounts more similar than could have imagined a few years ago, a series of recent studies have added substance to the claim that the specific resemblances of the Book of Giants to Moses 6–7—resemblances that are rare or absent elsewhere in Jewish tradition—are more numerous and significant than the resemblances of any other single ancient Enoch text—or, for that matter, to all of the most significant extant Enoch texts combined. Of particular note is new evidence in BG that relates to the Book of Moses account of Enoch’s gathering of Zion to divinely prepared cities and the ascent of his people to the presence of God.

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the Latter-day Saint community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

[Page 96]See Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, “Moses 6–7 and the Book of Giants: Remarkable Witnesses of Enoch’s Ministry,” in Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses: Inspired Origins, Temple Contexts, and Literary Qualities, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David R. Seely, John W. Welch and Scott Gordon (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Springville, UT: Book of Mormon Central; Redding, CA: FAIR; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2021), 1041–256. Further information at https://dev.interpreterfoundation.org/books/ancient-threads-in-the-book-of-moses/.]

The Latter-day Saint story of Enoch has been called the “most remarkable religious document published in the nineteenth century.”1 This is true for at least three reasons.

- First, the account is highly original. For example, according to a preliminary linguistic analysis by Stanford Carmack, the language of the account is by and large “independent of Genesis language,”2 with an initial authorship diagnostic strongly indicating that the text is not “pseudobiblical or biblical or Joseph Smith’s own pattern.”3

- Second, it is audacious in its claims. The account was produced early in Joseph Smith’s ministry—in fact, in the same year as the publication of the Book of Mormon—as part of a divine commission to “retranslate” the Bible.4 Like Doctrine and Covenants 76, it seems to contain many significant items that were removed “from the Bible, or lost before it was compiled.”5 Note that this statement allows for three options for the Enoch account in Moses 6–7: (1) it was removed from one of the books we now have in the Bible at some point in history; (2) it was written at some point but was later lost and was never connected with any of the books of the Bible; or (3) it was never written down until it was revealed to Joseph Smith.

- Third, it was produced at record speed. Judging by the rapidity by which similar passages were translated, the account of Enoch found today in Moses 6–7 would appear to have occupied only a few days of the Prophet’s attention.6 In view of the sizable revelations received on Enoch and other topics around that time, Kerry Muhlestein considers it “one of the greatest periods of revelation the Church has experienced, a true overflowing surge.”7

[Page 97]How Have Different Scholars Approached the Task of Explaining the Book of Moses Enoch Account?

There are a variety of different explanations for how such a novel, expansive, and coherent work purporting to be a true account of ancient historical figures could have been produced by a relatively unschooled translator in such a short amount of time. In the present study, our primary interest is in comparing Moses 6–7 with the Book of Giants (BG), an ancient source unknown in 1830, in support of arguments that the Prophet translated through a process that was dependent on divine revelation. Alternatively, some comparative studies seek to identify instances when Joseph Smith might have relied on texts known to him (whether from ancient or modern sources) as aids in the translation of Latter-day Saint scripture.8

Though it is not impossible that Joseph Smith drew inspiration “out of the best books” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:118; 109:7, 14) in his Bible translation, I have outlined in detail elsewhere the challenges that scholars face in their efforts to argue that nineteenth-century influences, augmented by the imagination of Joseph Smith, were primarily responsible for the Enoch narrative in the Book of Moses.9 For example, the evidence that the narrative of Moses 6–7 is derived largely from the Bible10 or scholarly Bible commentaries11 is scant and unconvincing at present. Evidence that Sidney Rigdon contributed significantly to Moses 7 is not persuasive and the first half of the acccount, Moses 6, was translated before he came on the scene.12

Most significantly, it would have been impossible for Joseph Smith in 1830 to have been aware of the most important resemblances to ancient Enoch literature in his translation. Other than the limited and typically loose parallels found in 1 Enoch (which was unlikely to have been available to Joseph Smith), the texts that would have been required for a modern author to derive significant parts of Moses 6–7 had neither been discovered by Western scholars nor translated into English.13 Additionally, even if relevant Enoch traditions from Masonry or the hermetic tradition had been available to Joseph Smith by 1830, it stretches the imagination to assume that they would have provided the Prophet with the suite of specific and sometimes peculiar details that are shared by Moses 6–7 and pseudepigrapha like 2 Enoch and 3 Enoch—and especially the Book of Giants.

[Page 98]Toward a Principled Examination of Literary Affinities in the Book of Moses

In evaluating the efforts to attribute the three large revelatory chapters of the Book of Moses to extant textual sources, Colby Townsend rightly concluded that “a systematic and detailed analysis of other literary influences on Moses 1 or the major additions in Moses 6–8 has not yet been completed.” title=”14. Ben Tov (pseudonym of Colby Townsend), “Book of Enoch.””14 While not sharing Townsend’s optimism that the Book of Moses narratives of the heavenly ascent of Moses (Moses 1) and of the ministry of Enoch (Moses 6–7) can be explained primarily through direct “literary influences” on Joseph Smith in the nineteenth century, I think there is great potential in performing “a systematic and detailed analysis” of literary affinities with ancient works the Prophet could not have known. For instance, an initial approach undertaken in this spirit that provides a favorable comparison of Moses 1 with the Apocalypse of Abraham, a work of Jewish pseudepigrapha not available to Joseph Smith, appears elsewhere in this conference proceedings.15 In the present paper, I take an analogous approach to the Enoch chapters in Moses 6–7—recognizing, of course, that much additional work remains.

Naturally, our expectations with respect to finding ancient threads in the Book of Moses must be qualified. Although Joseph Smith’s revisions and additions to the Bible sometimes contain stunning echoes of ancient sources, he understood that the primary intent of modern revelation is to give divine guidance to readers in our day, not to provide precise matches to texts from other times. Thus, it is not my claim that every word of these modern productions is necessarily rooted in ancient manuscripts. However, to believers it would be no surprise if long, revealed passages such as, most conspicuously, Moses 1, 6–7, were to provide evidence of having been drawn in significant measure from a common well of ancient textual or oral traditions.16

Rationale and Outline of the Present Study

The Book of Giants (BG), a fragmentary work discovered in Qumran in 1948, is one example of several ancient texts about Enoch unknown to Joseph Smith that exhibit remarkable affinities to the Enoch figure depicted in Latter-day Saint scripture. In section 1, I provide a brief overview of Hugh Nibley’s pioneering work comparing BG to Moses 6–7. I will also summarize a few of the subsequent discoveries by Latter-day Saint scholars who have built on Nibley’s pioneering research. These new discoveries by Latter-day Saint scholars were made possible by the increasing interest of Enoch scholars worldwide who have recognized [Page 99]BG as an important, and in many ways unique, window into ancient Enoch traditions.

Section 2 describes BG in more detail, showing why it has proven to be such a significant text for Enoch scholars and probing what has been called “conspicuous Mesopotamian influence” in its origins. Section 3 will provide specific background about BG that is necessary to understanding the rest of the study, dispelling common misconceptions about BG as a whole.

In the remaining sections, I will provide preliminary results of a deeper analysis that goes beyond the long-standing discovery of a pair of similar names in BG and the Book of Moses and the tantalizing but minimally explored listings of textual resemblances between the two texts that have been published previously. With respect to the similar names, section 4 will show why the BG names Enoch and Mahaway, cognates with the only two personal names mentioned in Moses 6–7, stand out from the other names mentioned in BG in ways that make them the foremost candidates for historical plausibility in an ancient Enochic setting.

From there, I will look at other similarities and differences between the texts. In section 5, I will compare the storylines of the Book of Moses Enoch account, BG, and other Enoch texts. The primary finding is that the broad storylines of Moses 6–7 and BG are remarkably similar. In addition, however, the editor(s) of BG seem to have wanted to add dramatic color to its narrative by inserting entertaining episodes about two giant “twins” into the account. Supporting the argument that these literary incidents are BG-specific additions is the fact that these characters and their stories are not only missing from the Book of Moses but also are found nowhere else in the ancient Enoch literature. Even more significant and surprising than these additions is the discovery that BG almost entirely leaves out the stories of sacred events that are found in Moses 6–7, despite the fact that each of these sacred events are touched on in one fashion of another in other ancient Enoch texts.

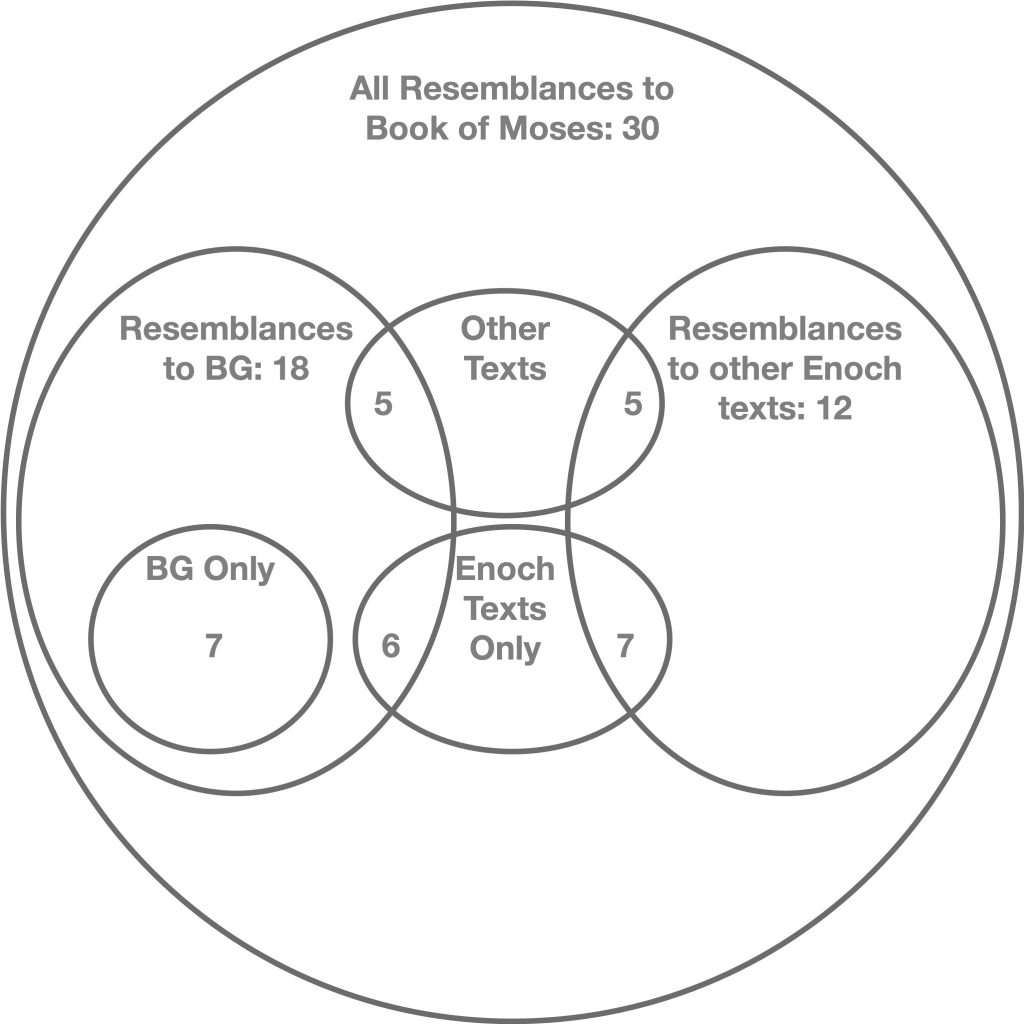

Section 6, a detailed analysis of thematic resemblances of BG to Moses 6–7, was inspired in part by an analogous study by the well-known Enoch scholar Loren T. Stuckenbruck.17 This analysis revealed that the eighteen thematic elements common to BG and the Book of Moses provide support for plausible arguments for a common well of ancient traditions that significantly influenced both texts. These common thematic resemblances are not only notable in their frequency and density but sometimes also in their specificity. Of great significance [Page 100]is that the common elements in BG and the Book of Moses nearly always are ordered in corresponding sequence. In the conclusion of this chapter, I will argue that the results of this study substantiate the claim that the specific resemblances of BG to Moses 6–7—resemblances that are rare or absent elsewhere in Jewish tradition—are more numerous and significant than resemblances to any other single ancient Enoch text—or, for that matter, to all extant ancient Enoch texts combined.

1. Previous Discoveries and Subsequent Findings

Hugh Nibley’s pioneering work comparing BG to Moses 6–7

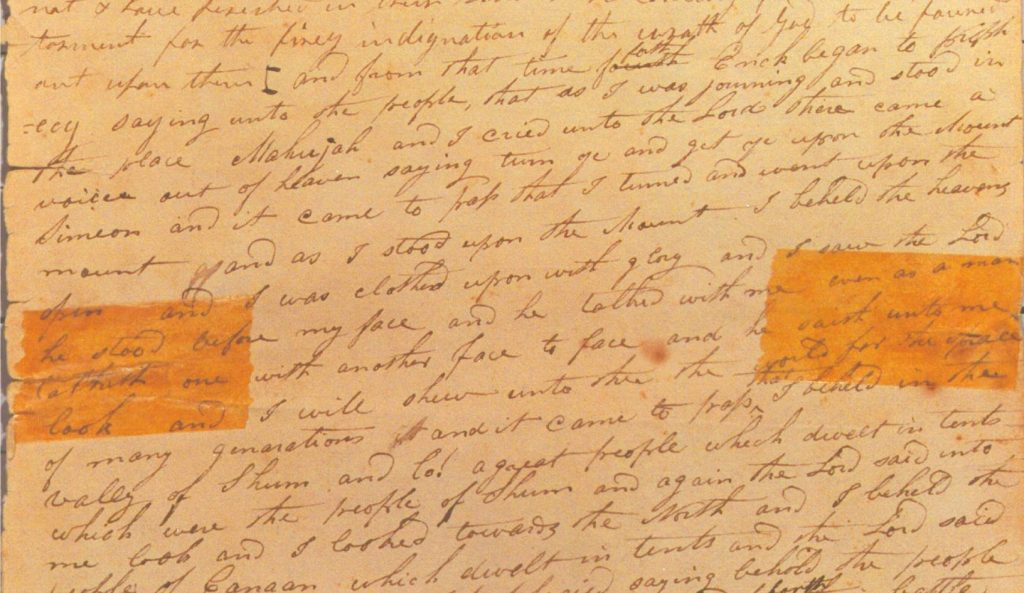

In 1976–77, Hugh Nibley dashed off one long, heavily footnoted article after another each month for a series about ancient Enoch manuscripts and Moses 6–7 that was running in the Church’s Ensign magazine. As he was finishing the last article in the series, he received—“just in time”18—an anxiously awaited volume describing fragments of Aramaic books of Enoch that were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.19 Among other texts, the book, edited by non–Latter-day Saint scholars J. T. Milik and Matthew Black, contained the first English translation of BG20. So impatient was Nibley to study it that it it seems he may have borrowed a copy from the University of Utah while he waited for his own copy to arrive.21

Figure 1. a. Title page of the last article in the Ensign’s “A Strange Thing in the Land” series;22 b. Title page of Milik and Black’s book that included the first English translation of the Book of Giants.23

[Page 101]As he worked quickly to meet his publication deadline, Nibley found many significant resemblances between BG and the Book of Moses. His best-known discovery is that of a remarkable match between a name in the Book of Moses and in BG. In the Book of Moses, the name appears as Mahijah or Mahujah and in English translations of BG it is usually given as Mahaway or Mahawai. Nibley found not only that the ancient form of these names were likely to have matched well but also that the roles of the corresponding characters were analogous.

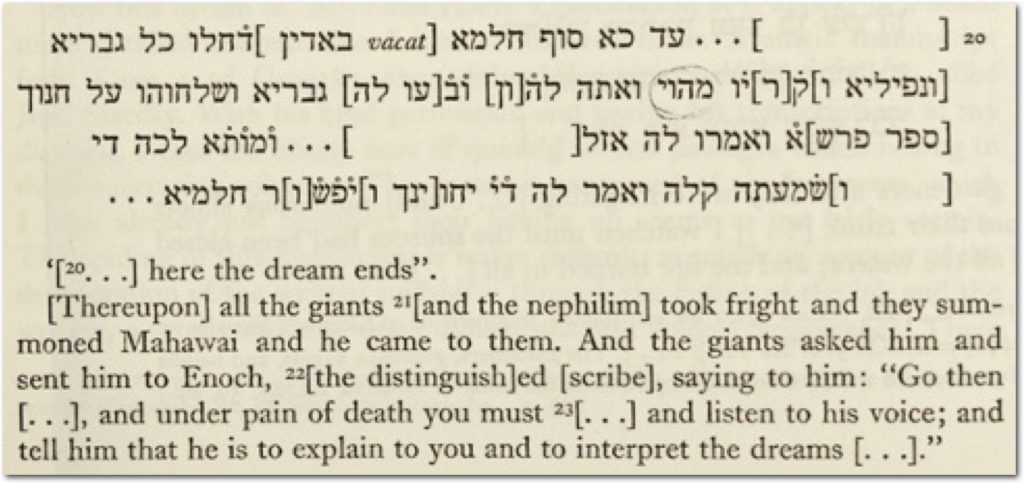

Figure 2. The passage shown comes from Milik and Black’s translation of BG, 4Q530, fragment 2, column ii, lines 20–23. It tells of an incident when the wicked ʾOhyah, Hahyah, and their fellows send Mahawai to ask Enoch about their frightful dreams of pending destruction. This copy of the book is located in the Hugh Nibley Ancient Studies Room of the BYU Harold B. Lee Library. Note that Nibley circled the Aramaic version of the name Mahawai in pencil.24

In 2020, Matthew L. Bowen, Ryan Dahle, and I extended Nibley’s early analysis.25 Our study confirmed and added new details and evidence to Nibley’s earlier findings while also addressing issues raised by Colby Townsend.26 In brief, Townsend argued that the names were not as similar as Nibley had originally concluded. He reasoned that “Nibley relied too heavily on his English transcription of both names—MHWY—and failed to recognize that the H [in the Book of Moses version of the name and the H in the BG version of the name represented] two distinct letters” in their presumed Semitic originals.27 However, in our later study we adduced relevant scholarship showing that despite a significant difference in one consonant in seemingly related texts (“Ḥ” [Bible] vs. “H” [BG]), there is currently no compelling reason why the BG name Mahaway (MHWY) could not have been related at some earlier point in its history both to the King James Bible name elements in Genesis 4:18, Mehuja-/Mehija- (MḤWY-/MḤYY-), and also to the [Page 102]only other names besides Enoch found in the Book of Moses: Mahujah (the English H corresponds equally well to MHWY or MḤWY) and Mahijah (MHYY or MḤYY).

Interest in Nibley’s discovery by non–Latter-day Saint scholars

Professor Matthew Black,28 a collaborator on Milik’s English translation of BG, was also impressed with the similarity of the BG and Book of Moses names. Like Nibley, he seems to have seen this finding as evidence that Joseph Smith’s Enoch text was ancient—even though he didn’t believe that Joseph Smith translated it through a process that relied on divine revelation. Instead, upon meeting Latter-day Saint graduate student Gordon C. Thomasson (who was familiar with Nibley’s Enoch research), Black initially suggested that a copy of a text that drew on the some of the same Enoch traditions as BG must have made its way to Joseph Smith sometime before the translation of the Book of Moses.29 Nibley said that during Professor Black’s visit to Brigham Young University (BYU) soon afterward, Black reiterated his view that Joseph Smith must have relied on an ancient source in his translation.30

More recently, Salvatore Cirillo, drawing on the similar conclusions of Stuckenbruck, stated that he considered the names of the gibborim, notably including Mahaway, as “the most conspicuously independent content” in BG, being “unparalleled in other Jewish literature.”33 [Page 103]Agreeing with the significance of Nibley’s finding, Cirillo concluded that “the name Mahawai in BG and the names Mahujah and Mahijah in the Book of Moses represent the strongest similarity between the Latter-day Saint revelations on Enoch and the pseudepigraphal books of Enoch (specifically BG).”34 However, in contrast to Matthew Black’s hypothesis that Joseph Smith must have been given an ancient record from an esoteric group in Europe, Cirillo did not make any attempt to explain how a manuscript that was unknown to modern scholars until the mid-twentieth century could have influenced the account of Enoch in the Book of Moses, written in 1830.

After Nibley’s initial look at BG and the Book of Moses, Nibley moved on to other subjects. Though Nibley continued to refer to his earlier Enoch findings in his later life, he did not engage to any significant extent with the burgeoning literature on Enoch that was published in the decades that followed.

Building on the foundation of Nibley’s research

Since Nibley’s passing, the growth of new scholarship on ancient Enoch texts has continued unabated. Building on the important context provided by Jared Ludlow’s survey of the full corpus of ancient Enoch texts and their implications for the Book of Moses Enoch chapters,35 the present chapter will focus specifically on BG. In addition to presenting recent research that confirms and deepens our understanding of passages originally discussed by Nibley, this paper will summarize new discoveries and analyses that further demonstrate the potential of BG as a fruitful source of study for students of Latter-day Saint scripture. Elsewhere I have published more extensive discussions of how ancient texts, including but not limited to BG, seem to confirm and complement the both the basic outline and specific details of the Enoch story in the Book of Moses.36

The present study, though still preliminary in some ways, aims to provide the most complete and in-depth comparative analysis of the Book of Moses to a single ancient Enoch text that has been undertaken to date:

- While Hugh Nibley’s pioneering research compared the names and roles of one character in Moses 6–7 and BG, the present study examines the names and roles of nearly all of the prominent figures in the two books.

- Whereas previous studies have touched on a few parallels in the overall storyline in the Book of Moses Enoch account that [Page 104]are found elsewhere in the ancient Enoch literature, the hope here is to reach a better understanding of the similarities and differences in the story elements across the entire storyline. Of particular interest are new arguments in support of the idea that Mahijah/Mahujah in the Book of Moses, like Mahaway in BG, encountered Enoch on two separate occasions.

- At a more detailed level, while earlier work has identified instances of close thematic resemblances or, in some cases, almost identical occurrences of rare terms and phrases, the aim here is not merely to identify such instances but also to explore in further detail each currently proposed candidate.

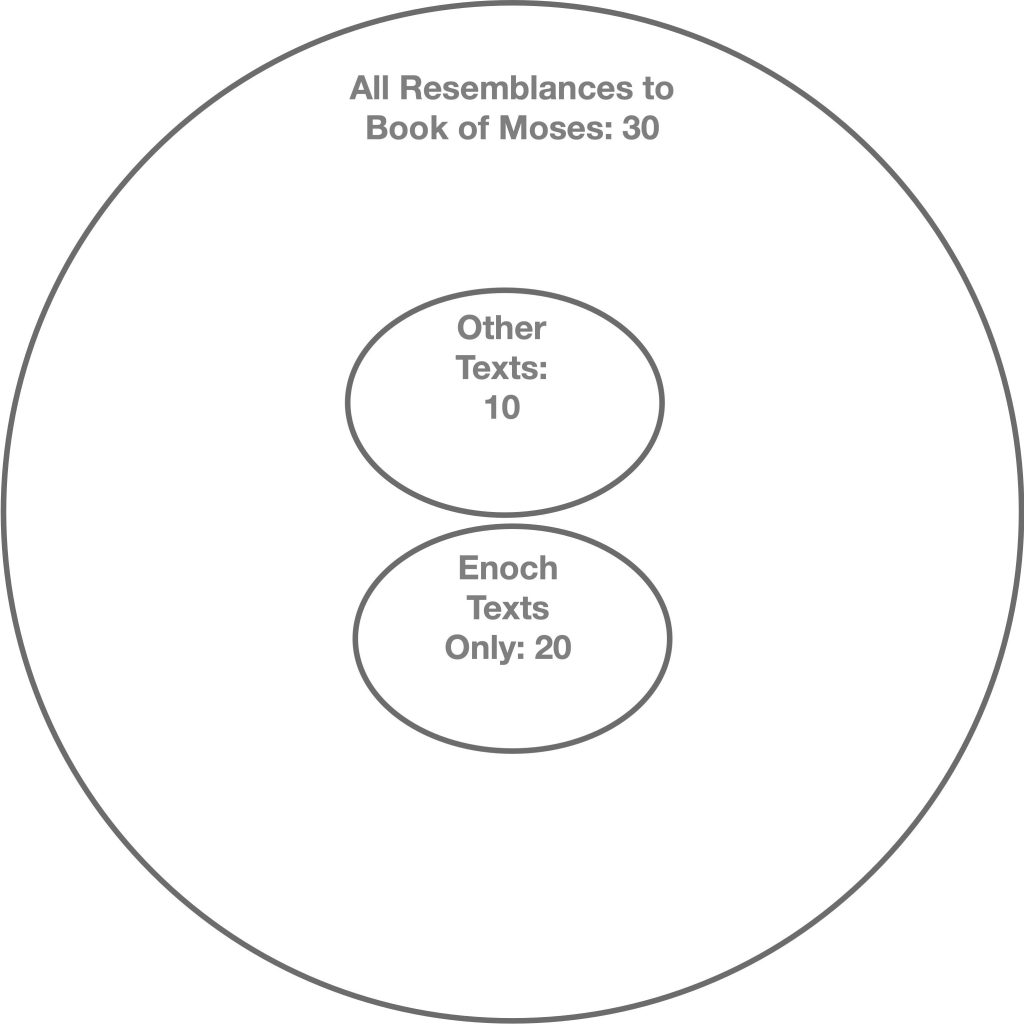

- Finally, for each thematic resemblance, this study will attempt to determine whether: 1. the theme is widespread in Second Temple Jewish traditions and the Bible; 2. generally confined to the ancient Enoch literature, or 3. specific to Moses 6–7 and BG. This result will tell us something about the evidential strength of resemblances by characterizing the degree to which the themes are widespread or rare outside the ancient Enoch literature.

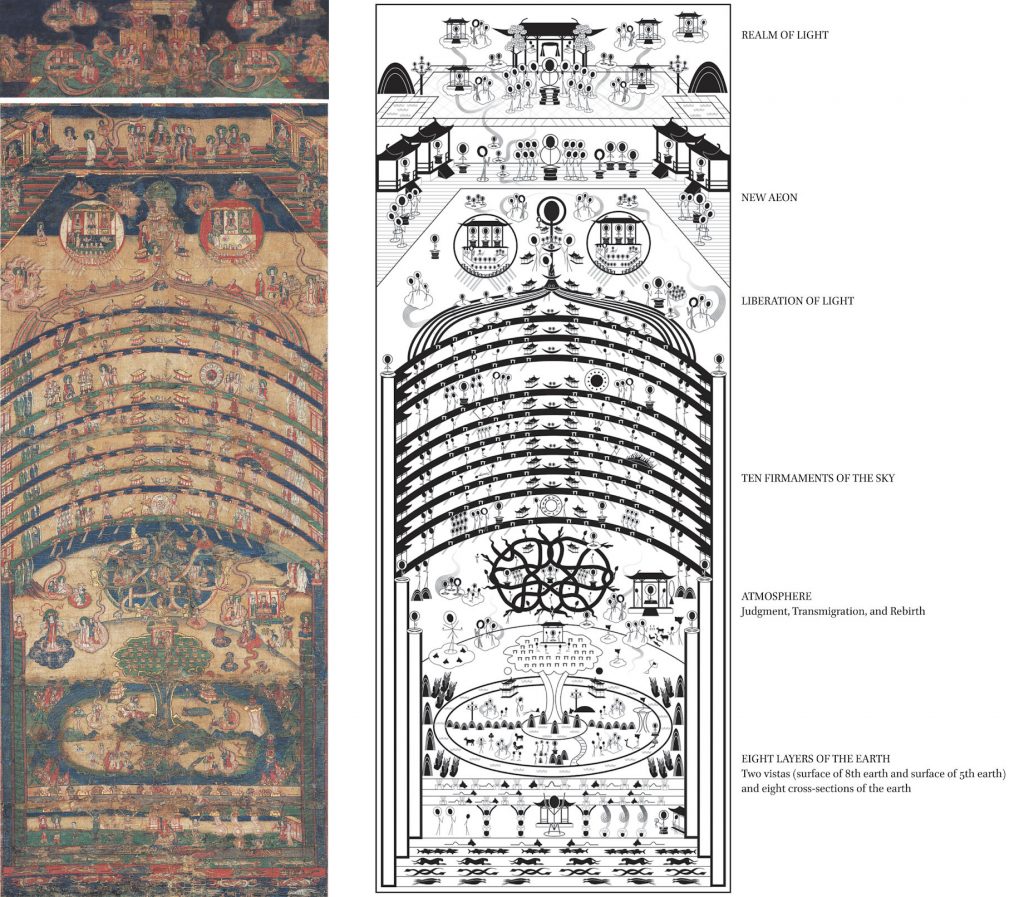

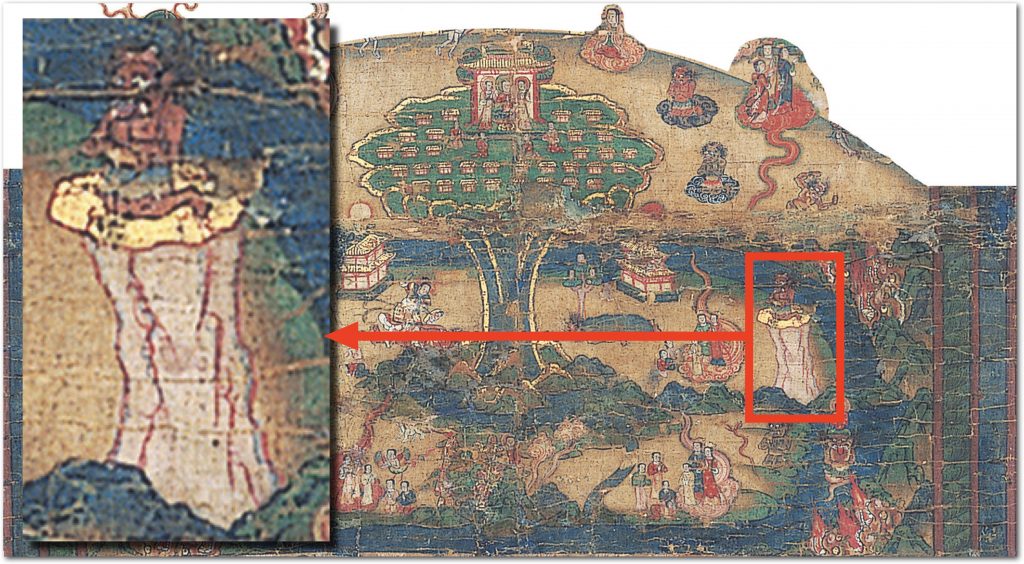

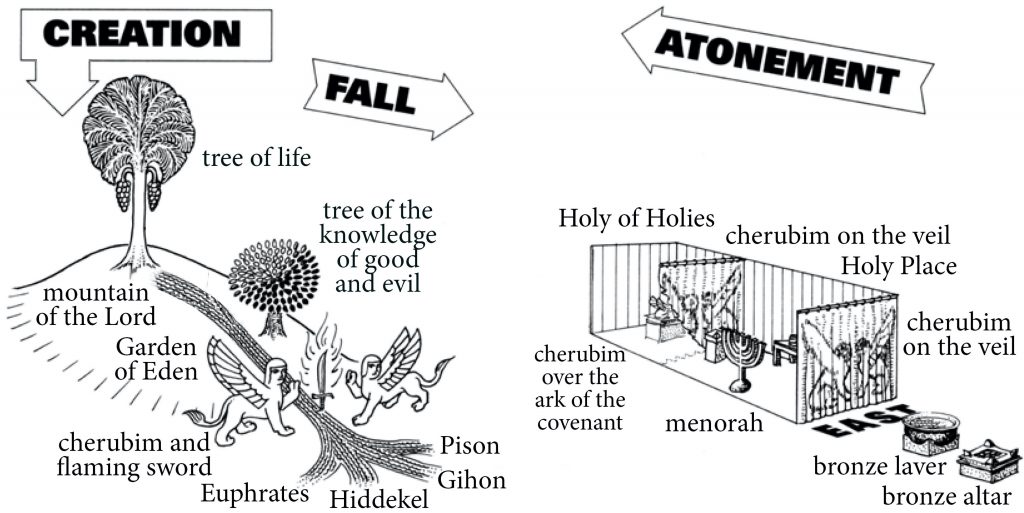

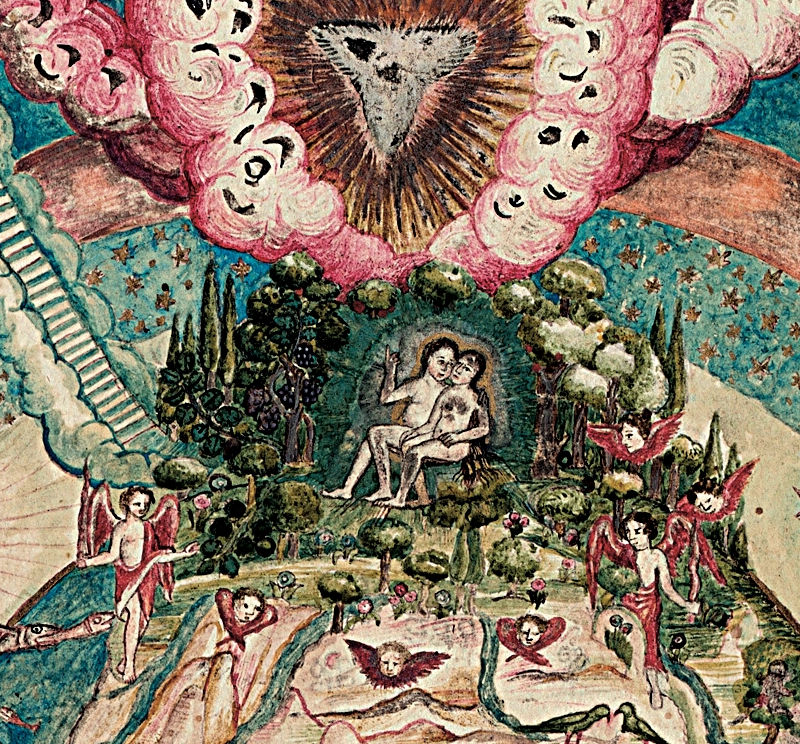

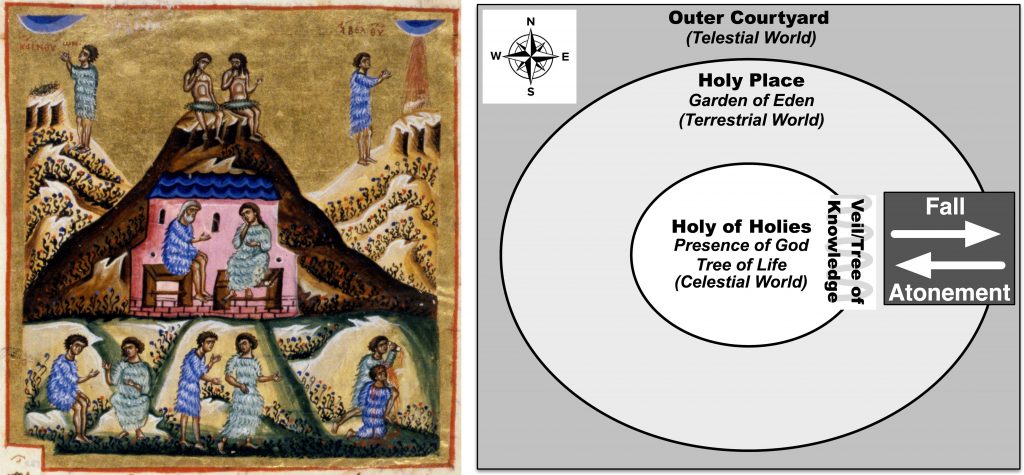

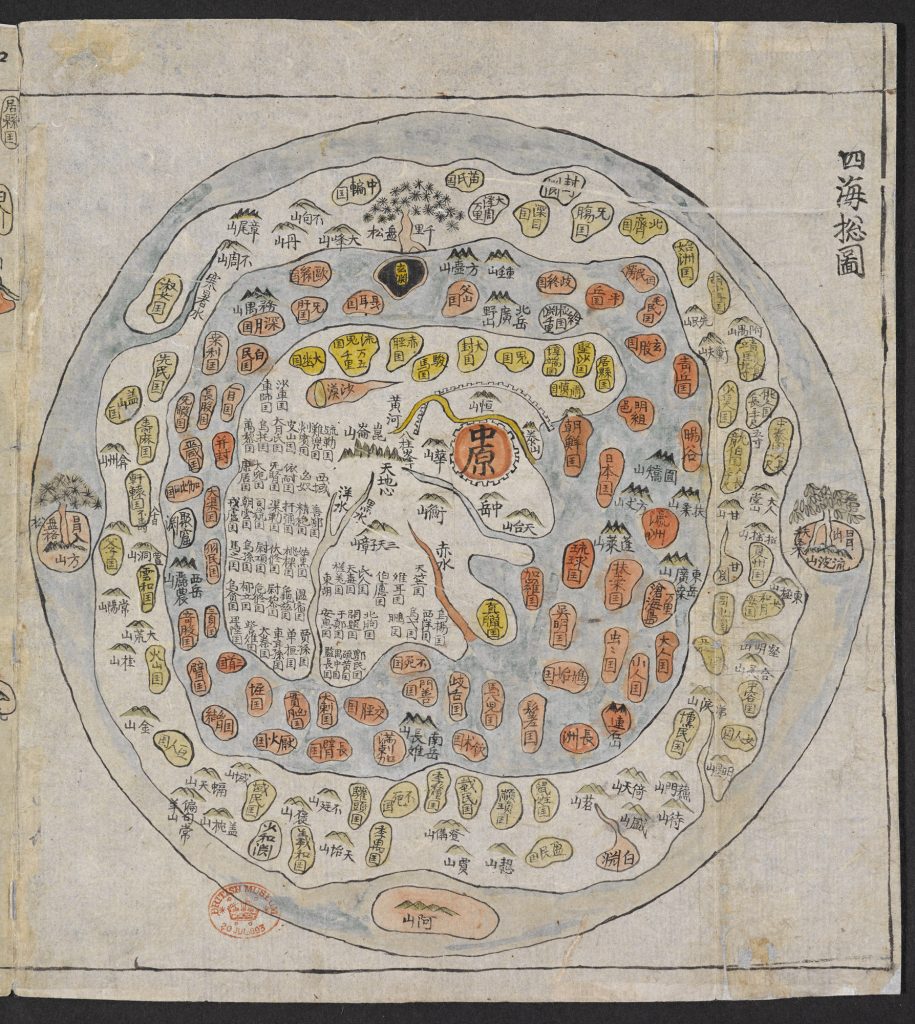

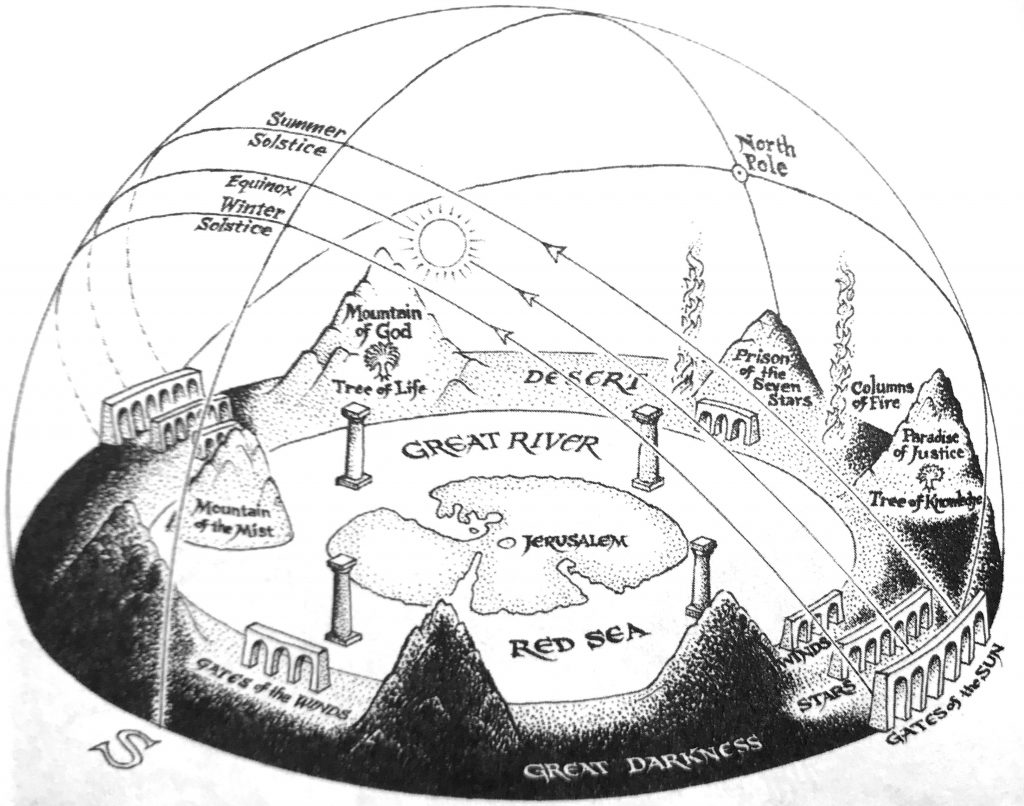

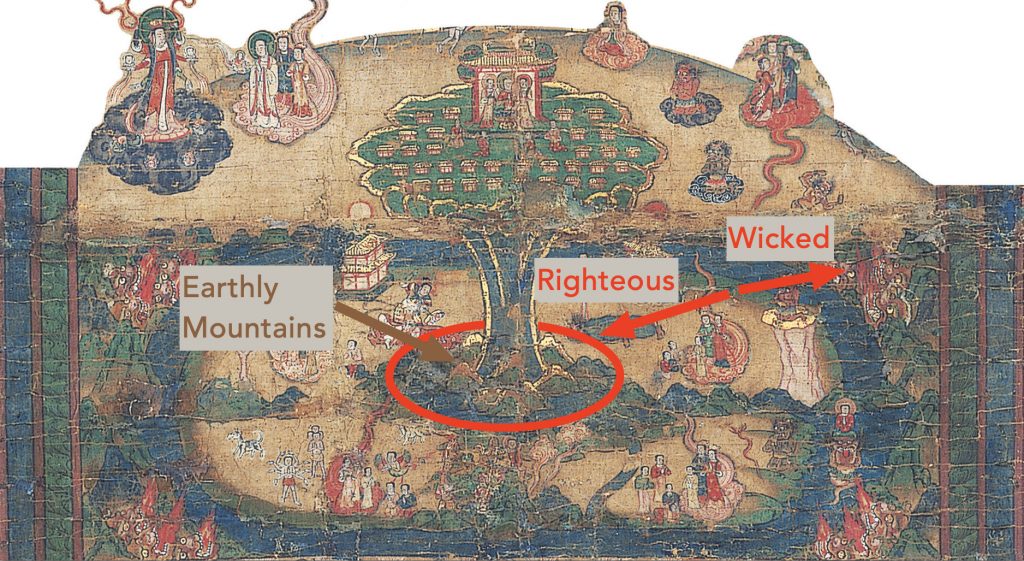

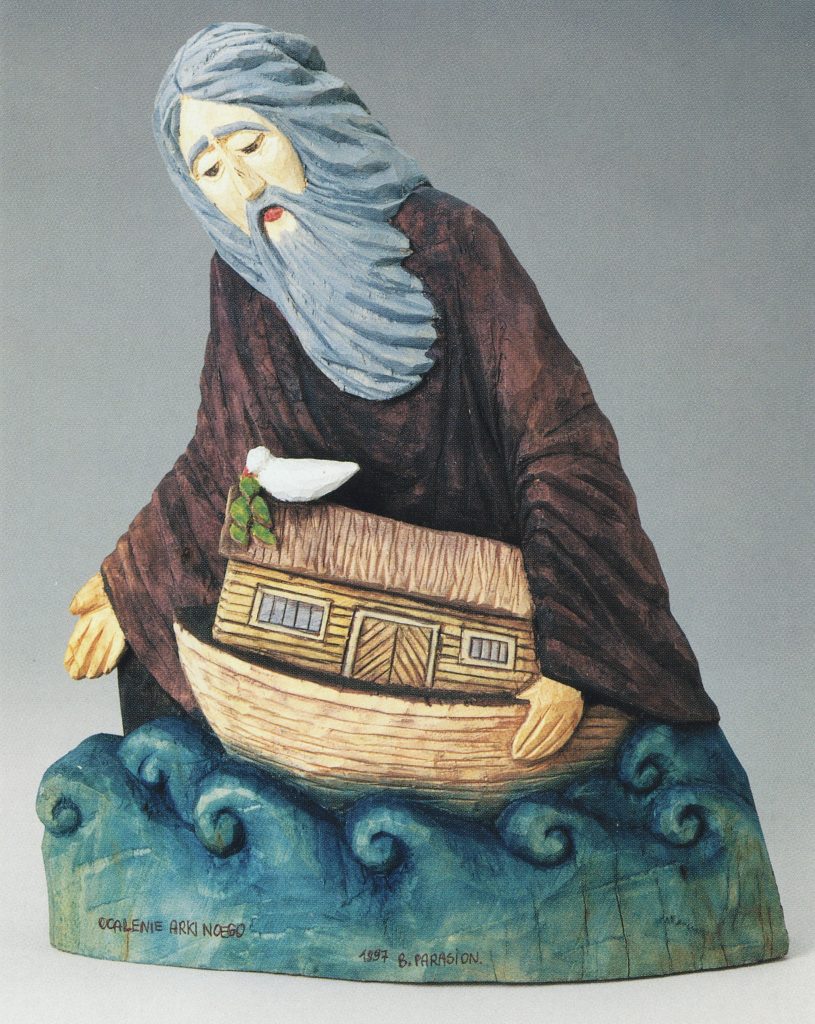

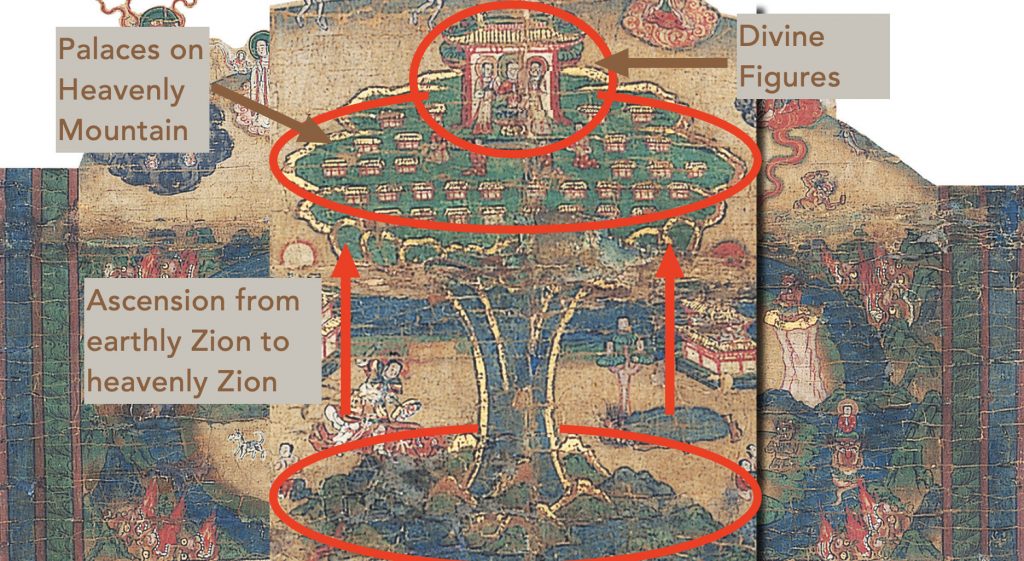

One of the most significant examples of new discoveries relating to the Book of Moses Enoch story is the collection of BG elements that relate to the report in Moses 6–7 that Zion, the righteous city of Enoch, was “received . . . up into [God’s] own bosom” (Moses 7:69). Though scholars have been aware for some time of suggestions in a Mandaean Enoch fragment37 and in late midrash38 that a group of Enoch’s followers were taken up to heaven with him, until recently no ancient evidence had surfaced for the idea that Enoch’s followers had been led to establish a place of gathering—an earthly Zion—beforehand. Recently, however, it was noticed that a fragment of a Manichaean version of BG describes how the righteous who had been converted by Enoch’s preaching were separated from the wicked and gathered to divinely prepared cities in westward lying mountains.39 This event recalls the statement of Moses 7:17 about the gathering of Enoch’s Zion, when his people “were blessed upon the mountains, and upon the high places, and did flourish.” Moreover, elements of the Manichaean Cosmology Painting (MCP), a visual representation that Enoch scholars have concluded contains depictions relevant to many events of BG, suggest that the inhabitants of those cities were ultimately taken up to dwell in in the presence of Deity.40 This motif recalls the Book of Moses statement that the inhabitants of Zion were “received . . . up into [God’s] own bosom”(Moses 7:69). [Page 105]Further discussion of this and other ancient affinities between BG and Moses 6–7 will be discussed later, in sections 3–6 of this chapter.

Before entering into further discussion of resemblances of BG to Moses 6–7, additional discussion on the background on BG will be provided below.

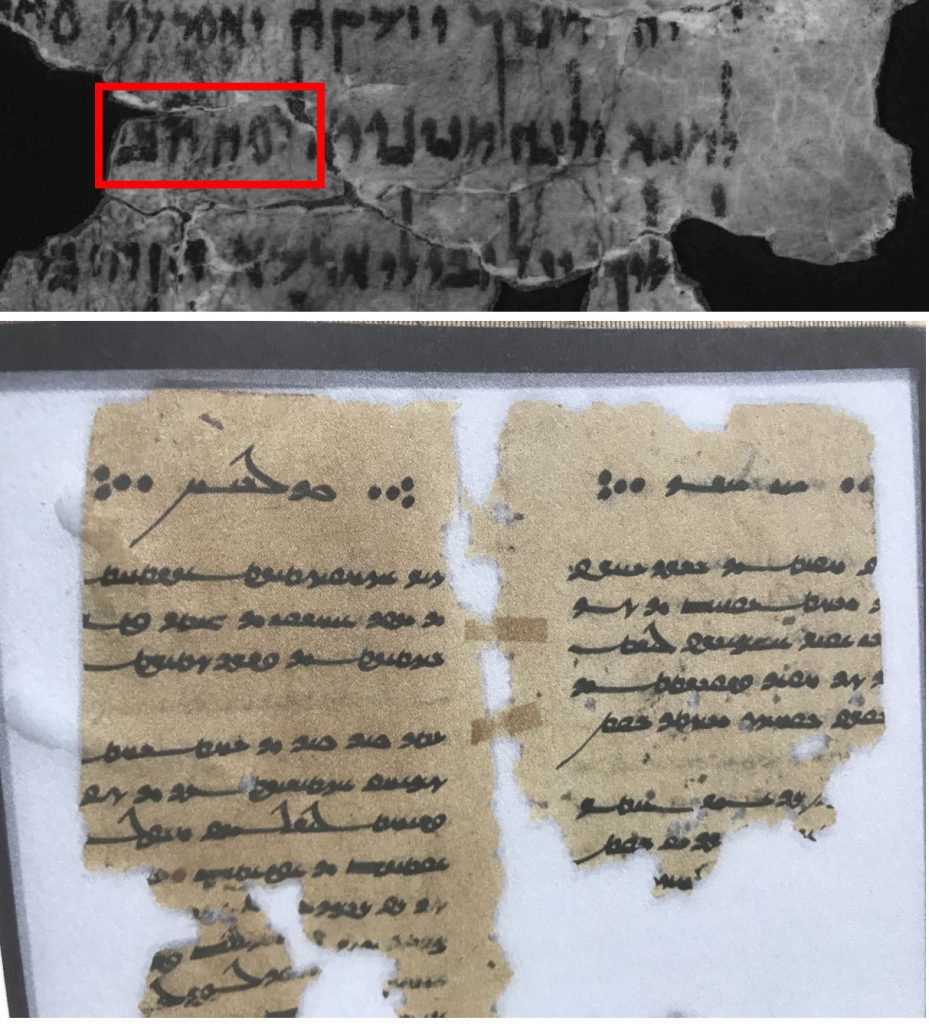

Figure 4. a. Photograph of a fragment of a Qumran BG manuscript in Aramaic showing detail of 4Q530 (4QGiantsb ar), fragment 7b, column ii.41 As an example of the difficulty in transcribing the fragments, the end of line 7 is outlined, showing where Milik and Black’s original transliteration LMḤWY resulted in their failure to recognize the name Mahaway in their English translation of the phrase.42 By way of contrast, Émile Puech’s newer transliteration, LMHWY, allowed Cook to translate the Aramaic characters as “to Mahaway”;43 b. Photograph of a Manichaean BG text fragment in Sogdian, showing detail of So20220/II/R/ and So20220/I/V/ [K20].44 Fragments of the Manichaean BG have survived in six different languages.

2. Introduction to the Book of Giants

What is the Book of Giants?

The Book of Giants (BG) is a collection of fragments from an Enochic book discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) at Qumran in 1948, supplemented by “extant fragments of the Manichaean Book of Giants published by W. B. Henning45 (and [later] by Werner Sundermann [and others]46) and in a Jewish writing designated the Midrash of Shemḥazai and ‘Aza‘el.”47 Significantly, it is not found as one of the books within the better-known Ethiopic compilation of 1 Enoch48 and, as a whole, [Page 106]resembles little else in the Enoch tradition. Before the discovery of the more extensive set of fragments of BG at Qumran, scholars had been made aware of its existence through related material in Talmudic and medieval Jewish literature, in descriptions of the Manichaean canon,49 in citations by hostile heresiologists, and in a small but significant collection of third- and fourth-century Manichaean fragments. For a variety of reasons, BG has proven to be of tremendous importance to Enoch scholarship.

Should BG be considered part of a “rewritten Bible”?

In brief, the answer is no. The consensus of modern Enoch scholars is that it is overly simplistic to conclude that texts such as BG were merely sectarian rewrites of Bible stories.

For one thing, it should be remembered that, as André Lemaire observes, “accepted texts” such as the books of the Bible as we think of them today simply did not exist at the time the Dead Sea Scrolls were copied.50 For this and other reasons, current biblical scholarship is increasingly giving way to methods that require, as John Reeves and Annette Yoshiko Reed describe, “a shift away from the older scholarly obsession with ‘origins’ whereby the study of scriptures often focused on the recovery of hypothetical sources behind them.”51 Instead, those who copied the Dead Sea Scrolls drew on “a rich reservoir or revered tales, ancestral folklore, and tribal traditions about the pre-Deluge era” that was much more extensive and ancient than the later edited, abridged, and harmonized books available in the Bible and collections of pseudepigrapha that have survived to the present day.52 An adequate study of relationships among these texts should be focused more on “interdiscursivity” rather than mere “intertextuality”53 (in the more simplistic sense that the latter term is sometimes used today).

Trying to make sense of the connections between the Aramaic BG, the Manichaean BG, and certain passages in medieval Jewish midrash, John C. Reeves argues that it is54

plausible to assume that these stories are . . . textual expressions of an early exegetical tradition circulating in learned groups during the Second Temple era. One version appeared in Aramaic at Qumran and was presumably the version later studied and adapted by Mani. Another version of the same tradition recurs in Hebrew in the Middle Ages. Still other versions (if not one of the two aforementioned [Page 107]ones) apparently influenced Islamic exegetes of the Qur’anic passage regarding the sins of Harut and Marut.55

Can BG be explained as a kind of “rewritten 1 Enoch”?

The skepticism of scholars such as Reeves, Reed, and Lemaire about characterizing works such as BG as part of a “rewritten Bible” further extends to doubts about the idea of BG being a “rewritten 1 Enoch,” in addition to the considerations raised above, it should be remembered that BG was “very popular at Qumran,” seemingly more popular than 1 Enoch itself.56 Besides being the most popular Enoch book at Qumran, BG is arguably also the oldest extant Enoch manuscript found anywhere.57 Thus, according to Enoch scholar George Nickelsburg, BG helps us to “reconstruct the literary shapes of the early stages of the Enochic tradition.”58 For these and additional reasons, BG is a document that should “be taken seriously in its own right,”59 rather than seen merely as an intriguingly anomalous yet on-the-whole insignificant afterclap of 1 Enoch.

In summary, caution should also be exercised in assuming any direct dependence at all of BG on 1 Enoch. Indeed, André Lemaire concludes that it is a bad idea to begin with to try and assimilate BG to 1 Enoch because “these two literary traditions are different and have had a different literary posterity.”60 The fact that BG (discovered in 1948 and the source of many of the most significant resemblances to Moses 6–7) owes relatively little to the Bible and 1 Enoch (the sources most often cited by those who think Joseph Smith was inspired by sources and ideas available to him in the nineteenth century) also lends support to the argument that the Enoch account in the Book of Moses is not simply a rewritten or expanded version of the Bible or 1 Enoch.

BG’s reliance on independent Mesopotamian traditions

Having concluded that BG is not primarily dependent on the Bible and 1 Enoch, some scholars have argued that Daniel, 1 Enoch, and BG independently draw on some “common tradition(s)” that are older than any of the three texts.61 In at least some cases, BG seems to have preserved such traditions “in an earlier form”62 than the other two. Intriguingly, Joseph Angel has concluded from his review of the evidence that BG “preserves only the remains of a complex allegory, whose original referents cannot be recovered.”63

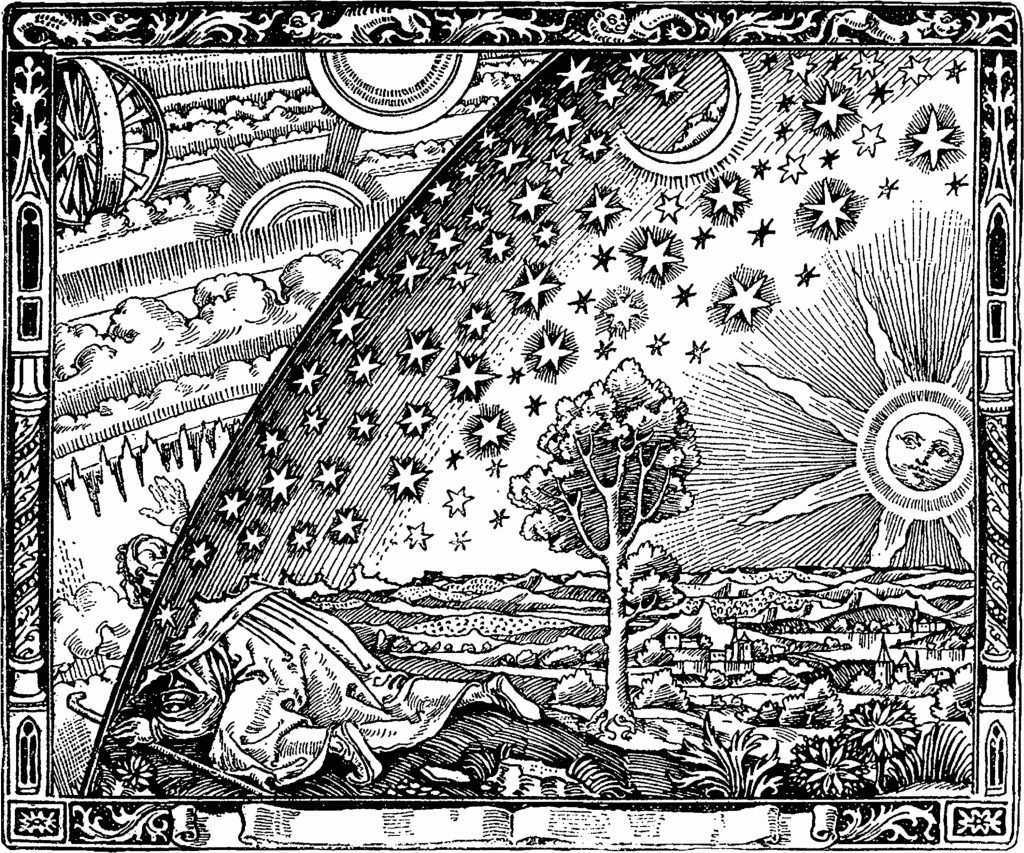

Both the antiquity and unique nature of certain elements of BG traditions can be better understood by looking “for the original of BG in [Page 108]an eastern diaspora”64—that is, ancient Mesopotamia. This conclusion is reinforced by more general observations of Dead Sea Scrolls scholars such as Ida Frölich that, “like the majority of Aramaic texts found in Qumran, the Enochic collection indicates a conspicuous Mesopotamian influence.”65 Seth L. Sanders has written at length about how physical transmission of ideas from scribal cultures from Babylon to Judea took place historically, with the common use of Aramaic as the key modality of exchange.66

More specifically, the Mesopotamian names in BG, not found elsewhere in the pre-Christian Enoch traditions, include Gilgamesh, the hero of the ancient epic by that name. The Gilgamesh epic is reputed by some to be the second oldest religious text currently known, rooted in Sumerian precursors that are dated to about 2100 BCE.67 Going beyond previous analyses, Matthew Goff has provided a reconstruction of the plot of BG, arguing that the text “creatively appropriates” not only names but also narrative “motifs” from the Gilgamesh epic.68 That the scribes were very capable of such appropriation is consistent with arguments that they belonged to a sophisticated class of individuals. For example, Daniel A. Machiela has concluded that the Aramaic texts at Qumran “represent the literary achievement of a highly learned, well-trained Jewish scribal group (loosely conceived), which wrote in an adept, literary Aramaic marked by a few notable dialectical features.”69 Of interest is the fact that in these Aramaic texts the God of Israel “is always called by more generic titles like God, Most High, or Lord of Eternity, and is never referred to by the Tetragrammaton.”70 “As opposed to the sectarian Hebrew texts at Qumran, the Aramaic cluster was intended for a wide Israelite audience, in diverse geographic locations.”71

In short, the seeming origins for some of the Enoch traditions in BG in ancient Mesopotamia, the antiquity and popularity of BG at Qumran, and its divergences from 1 Enoch—the only substantive ancient Enoch text published in English by 1830—make it a comparative text of singular importance for those interested in the possibility of ancient threads in the Enoch chapters of the Book of Moses.

Now, some additional context about BG that will be helpful in appreciating the detailed comparative analysis that will follow.

[Page 109]3. Some Things to Know about BG

There are no “giants” in the Book of Giants

A first thing to know is that there are no “giants” in the Book of Giants. The word translated as “giants” is gibborim, better translated as “mighty heroes” or “warriors.”72 As Frölich makes clear, “there is no sign that these beings had a mixed—human and animal—nature. The name gibborim [often mistakenly translated as “giants” in modern translations] refers to their state (armed, mighty men), not their stature which is described as gigantic in a single passage [in the ancient Enoch literature].73 The term . . . does not involve the idea of a superhuman or gigantic stature. It was the Greek translation that introduced a term (gigantes)74 involving the notion of superhuman stature.”75

This is important to understand because BG, like the Book of Moses, is mainly concerned with Enoch’s dealings with wicked people, the all-too-human gibborim. Both BG and the Book of Moses differ in this respect from 1 Enoch’s Book of the Watchers, which relates Enoch’s dealings with wicked superhumans, fallen angels with a fantastical physical form.

At some point, the terms gibborim and nephilim (the latter term originally used to refer to what seems to have been a remnant of a race of “giants”) were also equated in some contexts, leading to further confusion.76 Consistent with this distinction between two different groups, the Book of Moses Enoch account specifically differentiates “giants” (nephilim?) from Enoch’s principal adversaries (gibborim?).77 However, unlike BG (which sees the gibborim as the offspring of fallen angels called the Watchers78), the Book of Moses (like the writings of some prominent early Christian exegetes79) depicts Enoch’s adversaries as mere mortals. And rather than interpreting the “sons of God” mentioned in Genesis 6:4 as inhabitants of the divine realm, as is commonly done in the pseudepigraphic literature, the Book of Moses portrays them as the covenant posterity of Adam who have had that title bestowed on them by virtue of having received the fulness of the priesthood.80

[Page 110]

Figure 5. Fragmentary lion-hunting scene from Uruk, ca. 3200 BCE, on display at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, Iraq. The scene shows “a bearded figure wearing a diadem that appears twice; one at the top killing a lion with a spear and once below killing lions with bow and arrow.”81

Stories of gibborim were critiques of Mesopotamian culture

A second thing to know is that BG contains a critique of Mesopotamian civilization, a parody of the near neighbors of the Israelites in the east. While Mesopotamian legends relate stories that tell of the mighty deeds of their great sages and cultural heroes, BG describes the gibborim as arrogant warriors obsessed with their hunting prowess and with human bloodshed.82 According to Ronald Hendel, the primeval history in Genesis propounds a negative view of “the human propensity toward evil and violence,” specifically conveying “a cultural critique of Mesopotamia, whose kings were the dominant powers over Israel and Judah at the time of the crystallization of the traditions and texts in Genesis 1–11”:

According to the Hebrew Bible, history comes out of Mesopotamia, but it was a dubious and shameful history. . . . The ancient past in these stories offers implicit commentary on Mesopotamian civilization and empire in the present, colored by transgression, hubris, and a desire to rebel.83

If we examine what seem to be Jewish caricatures and parodies as critiques of Mesopotamian culture in BG within a broader context than [Page 111]those specifically provided by the Gilgamesh epic, possibilities for a bigger picture begin to come into better focus.84 For example, previous in-depth studies of recurring appearances and echoes of various peoples that were called gibborim in the biblical era allow us to understand the general social and geographic settings of Enoch’s prediluvial mission in BG and the Book of Moses in more specificity.85 For the present, abbreviated discussion and analysis of the Hebrew word gibbor itself provides a starting point to prime our intuitions. “Etymologically, with its doubled middle consonant,” writes Gregory Mobley, “gibbor is an intensive form of geber, ‘man.’ In this regard, as masculinity squared, gibbor roughly compares to the English compound ‘he-man.’”86 And in what manly qualities was a gibbor expected to excel? Brian R. Doak summarizes a relevant aspect of his sociolinguistic analysis of the culture of the gibborim in biblical times as follows:

As human-like embodiments of that which is wild and untamed, the biblical [gibbor] takes on the role of “wild man,” “freak,” and “elite adversary” for heroic displays of fighting prowess.87

The biblical reference to Nimrod as the first gibbor88 immediately brings to mind the earlier evocation of the “gibborim of old” in Genesis 6:4, and it is noteworthy that the Bible provides here a prototype of all gibborim in the figure of Nimrod. Though the text does not make it obvious that Nimrod is a “giant,” some lines of interpretation suggest that Nimrod was thought to be something greater than an ordinary human.89 In his biblical role, Nimrod is presented to us as a proud archetype of Mesopotamian civilization that is later described and satirized in capsule fashion within the Genesis 11 story of the Tower of Babel.90 From a geographic perspective, it does not seem to be a coincidence that the “land of righteousness” (Moses 6:41) of Adam, Seth, and Enoch is meant to be situated in the west, while both the land of Nimrod (which roughly equates to the land of Shinar, where the Tower of Babel was built) and the land of the wicked gibborim are said to be located eastward.91 This picture is consistent with the symbolic geography of BG and Moses 6–7 that is discussed later in the chapter.

The echoes of Nimrod’s hubris in Jewish traditions about the gibborim extend to the gibborim’s similar refusal to accept God as their master. Nimrod, like the opponents of Enoch and Noah, is presented as the spiritual progenitor of those who sought to make a name for themselves92 by building the Tower of Babel. In the gibborim culture [Page 112]portrayed in Genesis, as in the culture of “heroes” throughout much of secular history,

flesh is elevated above spirit, and the “name” of humanity is elevated above the “name” of God. In contrast to these heroes [stand Noah and Enoch], who [are] unique because [they have] found favor in the eyes of God.93 [They do] not achieve a “name” through strength and power, but through [their] relationship with God.94

While these broad, tentative conclusions about the possible shared Mesopotamian background, geography, and attitudes about the gibborim culture of BG, Genesis 6 and 11, and Moses 6–7 are necessarily conjectural, we will soon see that they are not inconsistent with the descriptions of the cast of selected characters in BG and the Book of Moses that we will now describe in more detail below.

4. Comparison of Selected Names and Characters in BG and the Book of Moses

One of the unique features of BG is that, “in contrast to other known contemporary Jewish apocalyptic literature, [it] actually provides names for some of the [gibborim].”95 Table 1 presents some of the most prominent members of the cast of characters in BG, grouped into rough categories that highlight their co-occurrences in other ancient pre-Christian texts/traditions and in the Book of Moses. Grouping the names in this fashion helps us gain insight into the rationale for why they may have been included in BG. In brief, I will argue that the redactor(s) of BG employed a strategy resembling the Victorian bridal custom of “something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue”96 as they selected or invented named characters to enrich the version of the story they inherited. The result is a broad panoply of names—some more and some less historically plausible—that served to advance their literary aims. By process of elimination, a closer examination of these names will throw light on the question of which of them provide the most promising evidence of historically plausible elements within BG and Moses 6–7. I discuss these names and characters by category below. A more extensive discussion of a few of the prominent names in BG and the Book of Moses has been published elsewhere.97

[Page 113]Table 1. Prominent names in Book of Giants

and co-occurrences in other texts

| Name | 1 Enoch | Mesopotamian | Genesis | Moses 6–7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ’Ohyah | ||||

| Hahyah | ||||

| Shemiḥazah | X | |||

| Baraq’el | X | |||

| Gilgamesh | X | |||

| Ḥobabish | Ḥumbaba98 | |||

| Enoch | X | Enmeduranki? | X | X |

| Mahaway | maḫḫû? | Mehujael? | Mahijah/Mahujah? |

’Ohyah and Hahyah

Meaning of the names. Enoch scholars have suggested that ʾOhyah (ʾWHYH) and Hahyah (HHYH) were intended as plays on the Hebrew verb “to be” (HYH) or, perhaps, on the Tetragrammaton, the Hebrew name of the Lord (YHWH).99 The specific proposal that the names ʾOhyah and Hahyah were inserted in BG as wordplay is consistent with a long history of analogous patterns across many different cultures and traditions.100 In these traditions, the two names relevant to the ones used in BG have always been presented as a pair101—indeed, very often as a pair of twins with rhyming names. When described as a single unit, as they so often are, they are variously labeled as “demonic twins,” “angels twain,” “two youths,” and so forth.102

Roles of the characters in BG. In BG, we are given a more complete portrait of ʾOhyah and Hahyah than for most of the other named characters in the text. Besides the probable origin of their names, their similar roles are distinctive within the account. For example, ʾOhyah and Hahyah are depicted as deceitful,103 ineffectual quarrelers,104 dreamers,105 and worriers106—doppelgängers afflicted with nagging doppelträumes. Despite being a member of the group that commissioned Mahaway to inquire of Enoch, ʾOhyah rejects the answer Mahaway brings back out of hand.107 In their appointed role, ʾOhyah and Hahyah seem almost to be sketched with the pen of a skilled caricaturist who has introduced a measure of comic relief that both pervades the larger narrative and persists in the very details of their Tweedledum- and Tweedledee-like [Page 114]names. Like Hergé’s Dupond and Dupont, part of the silliness of the two brothers is in the paradoxical fact that their “most singular quality is what is common to them,”108 a feature that is most obvious in the tellings of their two complementary dreams.

Figure 6. Painting of the Uygur Manichaean-Buddhist mural of the three-trunked “Jewel Tree” from Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, Cave no. 25 (no. 38 in the modern Chinese numbering system), Flaming Mountains, China, ninth–tenth century.109 For many years, scholars mistakenly interpreted the tree as portraying an element of the dream of the gibborim in the Book of Giants, where the flourishing tree with three trunks was seen as representing the idea that only Noah and his three sons would escape the Flood.110

Co-occurrences in other texts. In contrast to other BG characters, no mention is made of ʾOhyah and Hahyah in other ancient literature of the pre-Christian era, suggesting the likelihood that they are ad hoc inventions of the BG author(s). Moreover, while story characters equivalent to ʾOhyah and Hahyah appear in derivative medieval Jewish111 and Islamic112 accounts of the two dreamers, characters with names relating to Mahaway, Gilgamesh, or Ḥumbaba go conspicuously unmentioned in these late accounts. This fact highlights the virtual inseparability of ʾOhyah and Hahyah, as well as their literary independence from Mahaway, Gilgamesh, and Ḥumbaba.

Summary conjecture. These two late-appearing names do not appear to stem from ancient Enoch traditions, but rather seem to have been invented and inserted in the story for literary purposes.

[Page 115]Shemiḥazah and Baraq’el

Meaning of the names. Michael Langlois suggests that Shemiḥazah’s name was associated with a name of God (perhaps adding support for Stuckenbruck’s proposal of a theophoric –yāh termination in the names of Shemiḥazah’s sons ʾOhyah and Hahyah113). Langlois interprets the name as “Shem sees” (i.e., “the Name sees),”114 in which “the Name” refers to God. According to George Nickelsburg, the name “may be an ironic anticipation of the motif of God’s seeing the sins committed on earth. . . . In the very name that the angelic chieftain bears is the recognition that his sin will be found out.”115 Thus Shemiḥazah’s name, like that of his two sons, appears to be an object of wordplay.116

Baraq’el means “lightning of God,”117 referring to his role in 1 Enoch in teaching the mysteries of the signs of lightning flashes.118

Roles of the characters in BG. Both characters play minor roles in extant fragments of BG, and very little is said about them. Shemiḥazah is portrayed as a leader of Enoch’s adversaries: Enoch’s missive to the gibborim is addressed specifically to “Shemiḥazah and all [his] co[mpanions].”119 As mentioned above, he is the father of ʾOhyah and Hahyah.120 Baraq’el, on the other hand, is described as the father of Mahaway.121

Co-occurrences in other texts. In contrast to the small role given them in BG, these two characters are well represented in 1 Enoch.

Figure 7. Daniel Chester (1850–1931): The Sons of God Saw the Daughters of Men That They Were Fair, ca. 1923.122

There Baraq’el is said to be one of the twenty fallen Watchers, who are there listed by name.123 Specifically, Baraq’el is said to be the ninth chief,124 serving under the leader of the fallen Watchers, Shemiḥazah. Shemiḥazah and Baraq’el are said to have descended on Mount Hermon, [Page 116]where they “swore together and bound one another with a curse”125 after they determined that they would “choose . . . wives from the daughters of men.”126 Elsewhere in 1 Enoch, we learn the secrets that each of the heads of the Watchers revealed to humankind,127 and we read of their responsibilities in the governing of the seven heavens.128

Summary conjecture. In contrast to the singular appearance of ʾOhyah and Hahyah, Shemiḥazah and Baraq’el are prominent in other early Enoch literature. Though these and other fallen Watchers play a relatively minor role in BG, their presence seems to give a tip of the hat to older, common Enoch traditions that seem to lie behind both BG and 1 Enoch. They seem best conceived as representative literary types rather than unique historical characters.

Gilgamesh and Ḥobabish

Meaning of the names. Gilgamesh was the name of a legendary king of Uruk in the land of Sumer. He “appears in the list of Sumerian kings” and would have “flourished about 2750 BC.”129 The Epic of Gilgamesh has been aptly characterized as “fictional royal biography.”130 In the epic, Gilgamesh is described a gigantic figure who is two-thirds divine and one-third human.131

Figure 8. a. Indus Valley civilization “Gilgamesh” seal showing a “Master of Animals” motif—a figure between two tigers (2500–1500 BCE);132 b. Head of Ḥumbaba, second millennium BCE.133

Scholars have concluded that the name Ḥobabish is not of Hebrew origin. Rather, its first two syllables (Ḥobab) are related to the name of a second character from the Gilgamesh epic, Ḥumbaba. In the epic, Ḥumbaba is a gigantic monster with the face of a lion, a foe of humankind who guards the Cedar Forest. Wordplay on the name of Ḥobabish in BG [Page 117]suggests that he roared or howled with a “sound that is fitting for an animal.”134

Roles of the characters in BG. Scholarly consensus about a difficult passage in BG suggests that it is Gilgamesh who complains about his ignominious defeat at the hands of “all flesh,”135 which suggests (for readers of the Book of Moses, at least) the victory of Enoch and his people against their adversaries.136 Gilgamesh also responds to ʾOhyah’s mention of the latter’s frightening dream.137 Later ʾOhyah mentions Gilgamesh when he recounts to others what the latter had said.138

Only one or possibly two fragments of BG refer to Ḥobabish. In the first, the context suggests a negative reaction from Ḥobabish when he hears what ʾOhyah said about his conversation with Gilgamesh.139 If the second mention of Ḥobabish is properly restored from the fragment in which it seems to appear, it seems he was also involved in a plan to murder some of his fellows.140

Co-occurrences in other texts. As mentioned above, both figures are prominent in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Significantly, BG is the only early Enoch text to refer to them. Although both names have Mesopotamian roots and narrative motifs from the famous story are apparent in BG,141 “it is less evident whether on this basis one can maintain that the Book of Giants is familiar with the Gilgamesh Epic itself.”142

Summary conjecture. Stuckenbruck, following Reeves, suggests that “the author(s) of the Book of Giants have . . . integrated the names of such ‘pagan actors’ from the Epic [of Gilgamesh] into the storyline in order to communicate ‘a bold polemical thrust against the revered traditions of a rival culture.’”143 Matthew Goff differs from Stuckenbruck and Reeves, arguing that “the core goal of the composition is to portray the ante-diluvian giants as evil and recount their exploits and punishment, not to polemicize against the Gilgamesh epic, or [anyone or anything else]. The text creatively appropriates motifs from the epic and makes Gilgamesh a character in his own right.”144 In either case, the inclusion of the names Gilgamesh and Ḥobabish would seem to advance the redactor(s)’ interests by reinforcing the reader’s association of the tale with the perceived hubris of the Mesopotamian hero culture.

Enoch and Mahaway

Meaning of the names. Our discussion of Enoch (Enmeduranki?) and Mahaway (maḫḫû? Mehujael? Mahijah?) will necessarily be more extensive than that of the previous sets of names. For an in-depth discussion of the BG name Mahaway and possible relationships to [Page 118]Mehujael in Genesis 6:4 and Mahijah/Mahujah in the Book of Moses, the reader is referred to a previously published article by the author, Matthew L. Bowen, and Ryan Dahle.145 If, as argued eloquently by David Calabro, the names Mahijah and Mahujah were translated from a Greek source text for the Book of Moses written by early Christians, they “could have been rendered from their original Semitic forms, . . . just as the translators of the King James Bible used the forms “Abraham” and “Bethlehem” in the New Testament instead of the Greek forms “Abraam” and “Bethleem.”146

Elsewhere Bowen has written about the meaning of the name Enoch:

Significantly, Enoch (Henoch or Hanoch, Heb. ḥănôk) sounds identical to the Hebrew passive participle of the verbal root ḥnk, “train up” [or] “dedicate.”147 Thus, for a Hebrew speaker, the name ḥănôk/Enoch would evoke “trained up” or “initiated”—bringing to mind not only the general role of a teacher, but also the idea of someone who was familiar with the temple and could train and initiate others as a hierophant. Before it became the name of the post-Mosaic Feast of Dedication, the Hebrew noun ḥănukkâ had reference to the “consecration” or “dedication” of the temple altar (Numbers 7:10–11, 84, 88), including the sacred dedication of the altar for Solomon’s temple.148 Strengthening the connection of Enoch’s name to the temple, we note that in Egyptian, the ḥnk verbal root denotes to “present s[ome]one” with something, to “offer s[ome]thing” or, without a direct object, to “make an offering.”149 The Egyptian nouns ḥnk and ḥnkt denote “offerings.”150 In other words, it is a cultic term with reference to cultic offerings.151

It should also be mentioned that an Enoch-like figure is described in a tablet found at Nineveh, which can be dated before 1100 BCE.152 It tells of how Enmeduranki of Sippar, the seventh king of Sumer (before ca. 2900 BCE) was received by the gods Šamaš and Adad. According to Andrei Orlov, Enoch

is depicted in several roles that reveal striking similarities to Enmeduranki. Just like his Mesopotamian counterpart, the patriarch is skilled in the art of divination, being able to receive and interpret mantic dreams. He is depicted as an elevated figure who is initiated into the heavenly secrets by celestial beings, including the angels and God himself.153 He then brings this celestial knowledge back to earth and, similar [Page 119]to the king Enmeduranki, shares it with the people and with his son.154

Figure 9. Enoch ascends to heaven. British Library, MS Cotton Claudius B fol. 11v.155

The conjecture of a linkage between Enoch and traditions about Enmeduranki suggests the possibility of considerably more ancient roots for Enoch accounts than currently found in Jewish texts or hinted at in in the Gilgamesh epic.

In summary, whatever else one believes, it seems certain that Enoch was not invented out of whole cloth at Qumran.

With respect to the name Mahaway, I begin by observing that the vowels in the English transliteration of the Book of Giants name MHWY are largely a matter of conjecture at present, since no vowels appear in the Aramaic text. Compounding the difficulty for nonspecialists in recognizing similarities and differences in the spellings of ancient names is the fact that translators differ in their English transliteration. For example, the English letters j, y, and i are variously used to represent the Semitic letter yod. Thus, in English translations of the Book of Giants, we see several variants of the same name: Mahaway156 (the most commonly used), Mahawai,157 Mahway,158 and Mahuy159—or Mahuj, with the y transliterated with a j, as is frequently done with other names containing a yod in the King James Bible.

[Page 120]In discussing Mahaway, we should also consider the seemingly related names Mahijah/Mahujah from the Book of Moses and Mehujael in Genesis 6:4. Regarding Mahijah and Mahujah, we have English versions of the names containing vowels, but it is impossible to tell from the English text alone whether the second consonant in the names would have been written anciently as the equivalent of an H (as in the Book of Giants) or an Ḥ (as in Genesis 4:18). In other words, if we assume an ancient equivalent of the English name Mahijah, it could have been written either as MHYY or MḤYY. Likewise, Mahujah could have been written as MHWY or MḤWY.

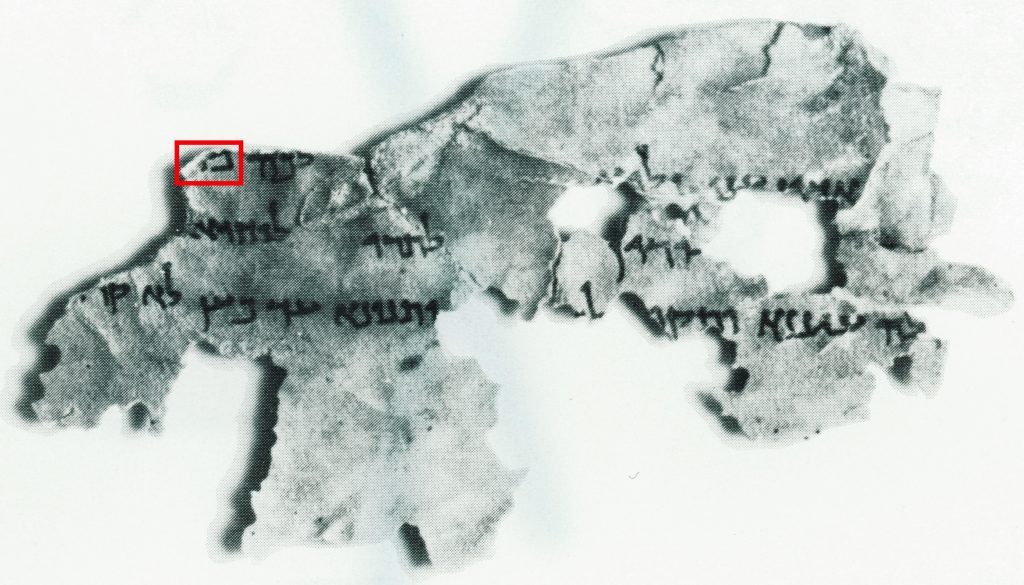

Figure 10. Fragment of the Qumran Book of Giants (4Q203) that was understood by Milik and Black to contain the first part of the personal name Mahaway (outlined by a rectangle in the upper left of the photograph).160 BYU professor Hugh Nibley was the first to argue that Mahaway (MHWY) is related to Mahijah (MHYY or MḤYY)161 and Mahujah (MHWY or MḤWY)162 in the Book of Moses.163

With respect to the similar name Mehujael, twice mentioned in Genesis 4:18, the Hebrew text spells the archaic name differently in each instance. In other words, though the name is spelled the same way both times in English (Mehujael), in Hebrew it is spelled once as Mehujael (MḤWY-EL) and once as Mehijael (MḤYY-EL).164 Notably, on one hand, the Book of Moses names resemble the two Hebrew versions of the name in Genesis 4:18 in that both a “u” and an “i” variant of the name exist. However, on the other hand, the Book of Moses names are both similar to the Book of Giants name in that they omit the “-EL” ending found in Genesis 4:18.

[Page 121]With regard to the meaning of Mahaway, Stuckenbruck has simply repeated the previous suggestion of Milik and Nickelsburg about ʾOhyah and Hahyah with a slight variation, concluding that, in the case of Mahaway (MHWY), “perhaps some derivation from the Aramaic verb ‘to be’ (HWY) in conjunction with a mem prefix is not impossible.”165 The laconic nature of his conclusion, including both a “perhaps” and a “not impossible,” is noteworthy. Differing from his predecessors, Stuckenbruck cited the possibility of wordplay on the Tetragrammaton only in connection with ʾOhyah and Hahyah, not Mahujah.166 The lack of evidence for wordplay leaves the reader bereft of a rationale for why the author of the Book of Giants would have invented the name Mahaway from scratch rather than adopting an already-known name from earlier traditions, as he did in the case of other characters such as Gilgamesh.

Why else might Stuckenbruck have been reluctant to commit himself to a derivation? Overwhelmingly, names in the ancient Near East and in ancient Israel follow rules of name formation. Though it is true that the name MHWY might putatively match a participial Aphel form of the Aramaic HWY (meaning “to create or cause to be”), there is a paucity of attested Aphel forms in the relevant literature. Thus, Stuckenbruck is even more diffident than Milik and Nickelsburg, suggesting that “the meaning of the name Mahaway . . . is impossible to decipher with any confidence,” speculatively offering only that “perhaps . . . the name includes a derivation from the Aramaic verb ‘to be’ [HWY] in conjunction with a mem prefix.”167 Evidently, Stuckenbruck is not willing on the basis of available evidence to commit to a nominal or a (participial) verbal form.

As with the BG name Mahaway, the etymology of the biblical name Mehujael remains uncertain. As Richard Hess observes, “It is generally agreed that Mehujael is composed of two elements, the second of which is ʾl,’ ‘god;’ [sic] but the first element is generally disputed.”168

In attempting to shed further light on the meaning of Mehujael, it can be said with certainty that the name Mehujael is older, perhaps much older, than the biblical text of Genesis as we have it today. If one limits an investigation of Mehujael to possible West Semitic etymologies, “West Semitic mḥʾ, ‘to smite,’ and a participial form of ḥyh, ‘to live’” are the most viable options for the disputed first element.169 However, limiting our search to West Semitic etymologies is an unreasonable requirement, since the ultimate origin of Mehujael and Mahaway seems at least as likely to be East Semitic as West Semitic. For example, although Ronald [Page 122]Hendel narrowly considers only Hebrew onomastics for the name Mehujael,170 Nahum Sarna171 and Richard Hess,172 following Umberto Cassuto,173 suggest that the name might be explained on the basis of the Akkadian maḫḫû, denoting “a certain class of priests and seers.”174

Further strengthening Cassuto’s argument for the derivation of the name is the agreement he finds in the word behind Mehujael (maḫḫû), the name of Mehujael’s son Methusael (a name that is “analogous not only in form but also in meaning”175), and the name of Mehujael’s grandson Lamech, which Cassuto sees as likely to have come from the Mesopotamian word lumakku, also signifying a certain class of priests.176 Significantly, Hess reports that while the root lmk is unknown in West Semitic, it is found both in third millennium BCE personal names and in names from Mari in Old Babylon in the early second millennium BCE.177

That the name Mahijah is the only name preserved in Moses 6–7 besides Enoch the prophet is evidence of Mahijah’s importance to the story. Similarly, Loren Stuckenbruck underlines the importance of Mahaway to both the Qumran and Manichaean versions of the Book of Giants. He observes a notable pattern of preservation in Chinese Manichaean fragments of the Book of Giants, which includes names of other individuals besides Mahawai that are, for one reason or another, significantly altered. Especially given the potential for “instances in which onomastic changes [i.e., changes in characters’ names] may have been due to the change of the language media,” Stuckenbruck is impressed with the “straightforward correspondence between the name(s) Mahawai in the Manichaean texts and Mahaway in the Aramaic [Book of Giants], in which the character, acting in a mediary role, encounters Enoch ‘the scribe.’”178

In summary, Enoch and Mahaway seem to differ from the other names that have been considered previously not only because there is no known literary motivation for their appearance in BG but also because both names have a plausible ancient Mesopotamian prehistory.

Roles of the characters in BG. Regarding the figure of Enoch in BG, scholars have observed that in the Aramaic BG, as in 1 Enoch, the prophet is portrayed exclusively as a remote figure “dwelling . . . with the angels”179 at “the ends of the earth, on which the heaven rests, and the gates of heaven open.”180 He seems to communicate exclusively through Mahaway, the messenger of the gibborim. And, once Enoch’s presence has been “veiled” after his heavenly ascent,181 even Mahaway is not in a position to see him in his transfigured state; they communicate only by [Page 123]voice.182 Enoch, as befits one whose traditional role in heaven is scribal, writes missives of revelation and judgment that Mahaway brings back to the gibborim. But, asks Wilkens,183 if it were true that Enoch could never communicate directly with the gibborim, what do we make of BG fragments that indicate he taught at least some of the gibborim directly?184 This seeming inconsistency poses no problem for the Book of Moses, which includes an account of Enoch’s preaching mission to the gibborim before his heavenly ascent, as I will discuss in more detail below. For the present, I will simply suggest that Enoch’s role in both BG and the Book of Moses in reproving and preaching to the gibborim is undertaken at first from earth and then from heaven.

As to the role of Mahaway, note that his primary role seems to be that of a serious-minded, message-bringing mediator.185 He seems to enjoy a unique relationship with Enoch, which seems to be one of the reasons why he is chosen by his peers as an envoy. More will be said about this below.

Co-occurrences in other texts. As seen in table 1, Enoch figures prominently not only in 1 Enoch, Genesis, and the Book of Moses but also in Mesopotamian texts, if one takes Enmeduranki traditions as being relevant.

With respect to the BG name Mahaway, there is currently no compelling reason why the Book of Giants name Mahaway (MHWY) could not have been related at some point in its history to the King James Bible name elements Mehuja- and Mehija- (MḤWY- and MḤYY-) and to the Book of Moses names Mahujah (MHWY/MḤWY) and Mahijah (MHYY/MḤYY). The rationale for this conclusion is more fully explained elsewhere.186

Provisional conclusion. As a literary figure, Mahaway is unique among all the characters of BG discussed above. Unlike ʾOhyah and Hahyah, there has been no strong argument to date for his name having been introduced into BG for the purpose of wordplay. In contrast to Shemiḥazah and Baraq’el, the appearance of Mahaway in the story could not have been motivated by a desire to link BG with currently known early Enoch traditions. Differing from Gilgamesh and Ḥobabish, the name is absent from the Gilgamesh epic and thus could not have been intended to provide Mesopotamian flavor to BG through well-pedigreed associations with that literature. All this helps us understand why the only two names mentioned both in the Book of Moses Enoch account (Enoch and Mahijah/Mahujah) and in BG (Enoch and Mahaway) stand out so distinctly from the other names.

[Page 124]Does the lack of a literary motive for the inclusion of Mahaway in BG make the alternative that the name was introduced, like Enoch, as part of a more ancient Enoch tradition more likely? When such a conjecture is added to the fact of Enoch’s possible connection to Enmeduranki and plausible origins of Mahaway as a name with ancient East Semitic roots, it becomes easier to lend credence to the suggestion that, of all the names mentioned in BG, Enoch and Mahaway may be the two most likely to share some basis in historical—rather than merely literary—traditions about Enoch. Of course, the ultimate basis for the acceptance of scripture lies in faith and divinely provided testimony, and the argument for the historicity of the scriptural characters can never be proven beyond the shadow of a doubt by an appeal to textual or archaeological evidence. However, evidential support for the antiquity of relevant names for Enoch and Mahaway/Mahijah/Mahujah in a milieu that is compatible with the scriptural setting and is otherwise consistent with ancient narrative motifs that parallel the scripture account creates additional space for rational belief in the material existence of ancient individuals that once stood behind both names.

In short, of all the prominent names in BG, Enoch and Mahijah/Mahaway, the only two names that appear in the Enoch story of the Book of Moses, also seem to be the most historically plausible.

Continuing with this line of argument, I will now show how storyline similarities and thematic resemblances to Moses 6–7 in BG draw on allusions to Mesopotamian culture and the distinctive name and role of Mahaway that I have already described to provide a somewhat faint but surprisingly coherent picture of shared narrative elements that seems to lie behind both Moses 6–7 and BG.

5. Comparing the Storyline of Moses 6–7 to BG and Other Enoch Texts

Table 2. Similarities and differences in major storyline elements

among BG, Moses 6–7, and other ancient Enoch literature

| Simplified Outline | Major Storyline Elements | Book of Moses | Book of Giants | Other Enoch Texts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introductory Events | ||||

| History of the Sons of God/Watchers and Their Progeny | X | X | X | |

| [Page 125]Call of Enoch | X | X | ||

| Violence and Secret Oaths/Mysteries | X | X | X | |

| Dreams and Antics of ’Ohyah and Hahyah | X | |||

| First Visit to Enoch | ||||

| Mahijah/Mahaway Encounters Enoch | X | X | ||

| Enoch’s Call to Repentance | X | X | ||

| Messianic Teachings of Enoch | X | X | ||

| Dreams and Quarreling of ’Ohyah and Hahyah; Mahaway Sent to Enoch | X | |||

| Second Visit to Enoch | ||||

| Mahujah/Mahaway and Enoch in a Sacred Place | X | X | ||

| Enoch Clothed in Glory | X | X | ||

| Parting of the Ways | ||||

| Wicked Defeated in Battle | X | X | ||

| Repentant Gathered | X | X | ||

| Concluding Events | ||||

| Enoch’s Grand Vision | X | X | ||

| Enoch’s People Are Taken Up to Heaven | X | X | X | |

The table above summarizes the results of an investigation to understand which of the major storyline elements of the Book of Moses are included in BG and other ancient Enoch literature. Of course, elements absent in surviving Qumran and Manichaean fragments of BG may be present in nonextant fragments. For example, most scholars have concluded that BG originally contained an account of a first visit of Mahaway to Enoch, which would seem to correspond to the first visit of Mahijah to Enoch in the Book of Moses, even though a BG account of Mahaway’s first visit does not occur explicitly in the text. More on that subject in a later section below.

[Page 126]In the table, three types of storyline elements are distinguished: (1) those that are part of what we are calling the “narrative core,” shown in normal typeface; (2) those that contain material relating to sacred teachings, heavenly encounters, or rituals, the kinds of events that David Calabro has highlighted in his paper in this volume,187 shown in bold; and (3) those that are unique to BG, appearing neither in Moses 6–7 nor anywhere else in the ancient Enoch literature, shown in italics.

Unexpected patterns in the table

The table exhibits some unexpected patterns:

- At least one fragment of every narrative storyline element of the Book of Moses is also present within BG (normal typeface). Notwithstanding significant differences in specifics, the basic storylines of both texts can be seen as sharing a similar focus and outcome. The BG account seems to begin with a brief reference to the Watchers that corresponds structurally to the genealogy of the righteous descendants of Adam who are called “sons of God” at the beginning of the Book of Moses Enoch account. But following this short introductory intrusion of the Watchers mythology into the BG story, there quickly follows—in sharp contrast to the Book of the Watchers in 1 Enoch—what Stuckenbruck calls a “most significant . . . shift of the spotlight from the disobedient angels”188 to the gibborim, who remain the focus in the remainder of the BG account.189 And as to the most significant outcome of the texts, the common concern of both BG and the Book of Moses Enoch account is ultimately the fate of the gibborim—proud self-styled human heroes—who either, on one hand, choose to reject Enoch’s message and are subsequently humbled by an ignominious defeat in battle or, on the other hand, choose to repent and eventually gather to a divinely prepared place from which they ultimately ascend to the divine presence.

- The sacred storyline elements in the Book of Moses are left out of BG, even though they are always present in some form elsewhere in the ancient Enoch literature (shown in boldface). The surviving fragments of BG, while preserving the same basic narrative core found in the Book of Moses, omit the most sacred and esoteric details of the account, including Enoch’s call; messianic prophecies in the preaching of Enoch; Enoch’s being clothed in glory; and the sweeping contents of his grand [Page 127]apocalyptic vision. The fact that variations on all these themes are prominent elsewhere in the ancient Enoch literature makes their virtual absence in BG a surprise, though there are precedents for the preparation and selective distribution of two versions of some Jewish and early Christian texts—one version for initiates that contains hierophantic teachings and the other for novices that leaves out such information.190 A brief discussion of each of these sacred story elements is given below and are discussed in greater length elsewhere.191

- Enoch’s call. In reading the account of Enoch’s call, its Johannine imagery in Moses 6:26–27 comes to mind. However, we are told by Samuel Zinner, that this seemingly New Testament imagery originally “arose in an Enochic matrix,”192 in other words, within literary traditions concerning the prophet Enoch. No less surprising in its relevance to the ancient Enoch literature is the unexpected co-occurrence of references to Enoch as a “lad” when he receives his prophetic commission in Moses 6:31 when seen in light of the prominence of “lad” as a title for the prophet in 2 Enoch, 3 Enoch, and the Mandaean Ginza.193 Additionally, the opening of Enoch’s eyes so he could see things “not visible to the natural eye” (Moses 6:36) is mentioned in 1 Enoch194 and 2 Enoch.195 Perhaps most remarkably, the fulfillment of the promise made to Enoch at his call that he would be able to “turn [waters] out of their course” (Moses 6:30), although appearing nowhere else in scripture, is described in the Ginza Enoch account.196

- Messianic titles and prophecies in the preaching of Enoch. The striking equivalents of each of the titles mentioned in Moses 6:57—”Only Begotten,” “Son of Man,” “Jesus Christ,” and “Righteous Judge”—are described in the pre-Christian Book of Similitudes in 1 Enoch197 and related Jewish traditions. Elsewhere in S. Kent Brown and I describe these and other relevant affinities in the Second Temple Tradition to Moses 6–7.198 In this context, it may be noteworthy that some aspects of the knowledge about the last days and the “Righteous One” revealed to Enoch in the Similitudes are explicitly mentioned as being among the “hidden things” not to be shared publicly or, in some cases, not be to be committed to writing at all.199 (Were any of the other sacred storyline elements “missing” in BG also similarly considered?)

- [Page 128]Enoch’s being clothed in glory. The pseudepigraphic books of 2 and 3 Enoch purport to describe the process by which Enoch was “clothed upon with glory” (Moses 7:3) in more detail. As a prelude to Enoch’s introduction to the secrets of creation, both accounts describe a “two-step initiatory procedure” whereby “the patriarch was first initiated by angel(s) and after this by the Lord” Himself.200 In 2 Enoch, God commanded his angels to “extract Enoch from (his) earthly clothing. And anoint him with my delightful oil, and put him into the clothes of my glory.”201 Third Enoch tells us that after Enoch was changed, he resembled God so exactly that he was mistaken for Him.202 As this process culminates, Enoch, both in ancient sources and modern scripture, receives “a right to [God’s] throne.”203 As in other instances of sacred episodes, BG does not explicitly detail these events.

- Enoch’s grand apocalyptic vision. Compare Enoch’s grand vision in Moses 7 with the tour of heaven and vision of the future that are among the principal themes of 1 Enoch, 2 Enoch, and 3 Enoch.204 In contrast to BG, which seems to conflate Enoch’s temporary heavenly ascent during the visit of Mahaway with the event of his definitive translation to heaven, accounts in other Enoch texts make it clear that these were two separate events. In other words, while BG seems to end Enoch’s direct earthly ministry at the time of his initial ascent, other Enoch texts, consistent with the Book of Moses, have him continuing his earthly ministry afterward until the moment that he and his people rise together to the divine presence.

- The BG-unique themes notably include the dreams, antics, and quarreling of ’Ohyah and Hahyah (shown in italics). Earlier I argued that, of all the prominent names in BG, these two names are the ones that most look like they were invented out of whole cloth in BG.

Describing these patterns differently, one could summarize by saying that if you look at the vertical column for BG across all the storyline elements, you will notice that every entry is either in regular typeface or italics—none are in bold. In other words, BG contains something relating to every narrative core story element found in the Book of Moses while containing none of its sacred storyline elements, even though hints of each of the “missing” sacred elements are found in one form or anther elsewhere in the ancient Enoch literature. Indeed, [Page 129]the resemblances between Moses 6–7 and BG in the narrative core story elements are so striking that one is tempted to speculate that BG and the Book of Moses were rooted in some of the same ancient Enoch traditions but that somewhere along the line, the sacred stories now found only in the Book of Moses were either removed from the tradition inherited by the BG redactor(s) or, alternatively, were left out when BG was composed.

Other items of note

The synoptic outline makes obvious the primary bipartite division of the story of Enoch in the Book of Moses into an earth-focused mission followed by a heaven-focused commission. More specifically, while Moses 6 is primarily concerned with Enoch’s initial divine call to preach repentance and salvation to the wicked on earth, the major preoccupation of Moses 7 is Enoch’s subsequent heavenly commission as a new member of the divine council205 and the preparation of his people to meet God face-to-face (see Moses 7:69). Analogous doubling of other themes in BG has been highlighted previously by Stuckenbruck.206

Finally, it should be observed that the overall tone of the BG account differs from that of Moses 6–7. Moses 6–7, though at times exploiting elements of humor and irony in its account, is generally sober in tone, is firmly rooted in the material world of humankind, and is illuminated by the apocalyptic visions of the prophet Enoch. BG, on the other hand, seems to be much more of a polemical parody on Mesopotamian gibborim culture, is occasionally tainted with the mythical elements of the Watchers, and, while missing the detail of the sacred accounts of Enoch’s call, teachings, and visions, adds the harrowing dreams of the inept, anxiety-ridden, and ultimately tragicomical characters ’Ohyah and Hahyah.

6. Detailed Analysis of Thematic Resemblances of BG to Moses 6–7

Elsewhere in the present volume, an extended discussion of approaches to address the potential pitfalls in comparative analysis has been provided.207 The detailed analysis in the present chapter draws inspiration from Enoch scholar Loren Stuckenbruck’s study of possible influences of 1 Enoch on the New Testament book of Revelation.208 In that study, he concluded from a discussion of a set of resemblances in both works “that the writer of [the later text] was either directly acquainted (through literary or oral transmission) with several of the major sections of [the earlier text] or at least had access to traditions that were influenced by these writings.”209 [Page 130]Significantly, he argued for the likelihood of his conclusion, even when realizing that “at no point [could] it be demonstrated that the [later text] quotes from any passage in [the earlier text].”210

The primary question that motivated Stuckenbruck’s study is reasonably similar to our own, except that in our case we know that Joseph Smith could not have been acquainted with BG (since it was lost to modern scholarship until 1948), so any persuasive evidence of a literary association between the two texts would have to be interpreted as a demonstration that BG and the Book of Moses were independently influenced by similar ancient Enoch traditions that informed and antedated both of them.

In Stuckenbruck’s comparison and analysis, he provided a table for each potential resemblance. In each table there were three columns: one column describing the topic of interest common to the resemblance and the other two columns containing the seeming parallels as found in each of the two texts. Since the parallel texts were in different languages, their rendering was given in English. The table for each resemblance was followed by a brief discussion describing and analyzing the similarities and differences in the selected texts.211

In this section, I will do something similar for eighteen thematic resemblances of BG to Moses 6–7. By the term “thematic resemblances,” I mean instances in which reasonably similar topics of discussion occur in both texts, even when some elements and perspectives differ. The criterion of thematic similarity rather than identical vocabulary is appropriate because, like Stuckenbruck, I will be comparing two English translations. All but two of the seventeen thematic resemblances are supported by multiple sources within BG textual and visual depictions.

In the results section of the study that follows the presentation and analysis of each resemblance, we will not only consider the number of resemblances, their density, the degree of correlation in their order of appearance within the presumed BG storyline sequence (according to the current storyline sequencing conjectures of Stuckenbruck), and the range of their extent through nearly the entire storyline, but also, like Stuckenbruck, their specificity as another proxy measure of the strength of association between BG and the Latter-day Saint Enoch account. Thematic resemblances to Moses 6–7 that are exclusive to BG and the Book of Moses will be deemed stronger than ones that appear in other ancient Enoch literature, and resemblances for themes that are rare or absent outside the ancient Enoch literature will be seen as stronger than ones that also occur elsewhere within Second Temple texts and the Bible.

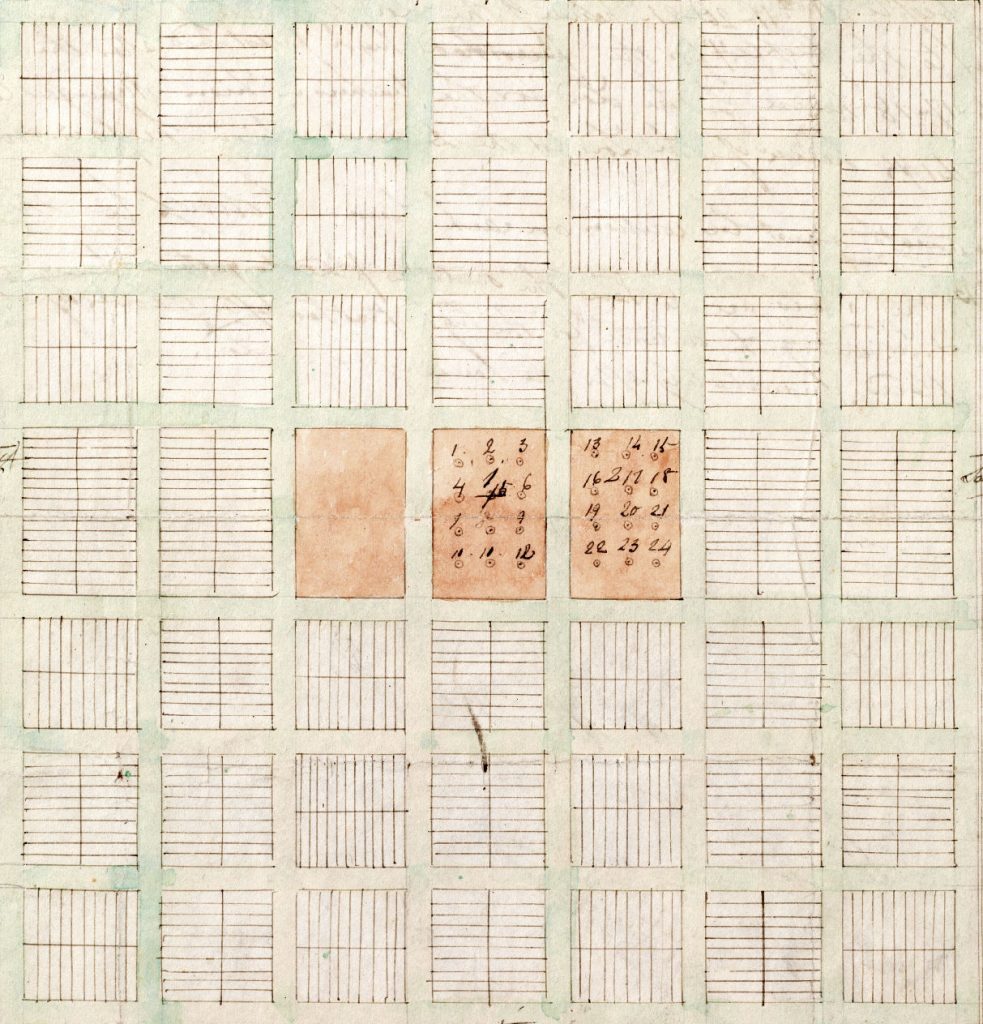

[Page 131]Description of the table of thematic resemblances

Eigtheen thematic resemblances are summarized in the table below. The resemblances have been sequenced with reference to the chapter-and-verse order in the Book of Moses in which they appear.212 Specific citations of passages in Moses 6–7 and BG follow in the second and third columns.