Abstract: For many theories about the Book of Abraham, the Egyptian Alphabet documents are seen as the key to understanding the translation process. While the original publication of those documents allows many researchers access to the documents for the first time, careful attention to the Joseph Smith Papers as a whole and the practices of Joseph Smith’s scribes in particular allows for improvements in the date, labeling, and understanding of the historical context of the Egyptian Alphabet documents.This essay supports the understanding of these documents found in the other volumes of the Joseph Smith Papers that the Egyptian Alphabet documents are an incidental by-product of the translation process rather than an essential step in that process.

This study comes as a response to an invitation by principals of the Joseph Smith Papers Project to examine Revelations and Translations Volume 41 more closely. In this paper, I consider only the section on the Egyptian Alphabet documents. While doing so, however, I must correct a number of errors and misconceptions promoted in the volume about the documents.

I note at the beginning that the volume editors do not necessarily demonstrate a consistent or coherent line of thought about the documents and will not infrequently contradict in one place what they say in another place. This could be evidence of at least two possibilities: (1) unacknowledged fundamental disagreements among the editors [Page 78]about the nature of the documents with which they were working had different editors adding different comments to the text without realizing they contradicted other passages in the text; (2) the editors simply did not think about how the different parts of what they were doing fit into a larger whole.

Description

Three documents in the Church History Library either bear or are assigned the title “Egyptian Alphabet.” These are Church History Library ms. 1295 fd. 3‒5. They are published under the following rubrics:

| Manuscript Number | JSP Designation | Published In | Handwriting | Leaves |

| Ms. 1295 fd. 3 | Egyptian Alphabet, circa Early July‒circa November 1835-C | JSPRT4, 85–93 | W. W. Phelps | 4 leaves |

| Ms. 1295 fd. 4 | Egyptian Alphabet, circa Early July‒circa November 1835-A | JSPRT4, 55–71 | Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery | 4 leaves |

| Ms. 1295 fd. 5 | Egyptian Alphabet, circa Early July-circa November 1835-B | JSPRT4, 73–83 | Oliver Cowdery | 4 leaves |

The manuscript leaves are written on only one side, with the exception of the Egyptian Alphabet containing Joseph Smith’s handwriting in which the last leaf has been flipped vertically and writing added to the back.

The documents are related in that they have the same title. Their content is similar but not always identical. In the eyes of many this set of documents is seen as the key to understanding Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Abraham, and they therefore deserve more careful scrutiny.

Date

The Joseph Smith Papers gives the date of the Egyptian Alphabet Documents as “Early July‒circa November 1835.”2 The editors claim that the Egyptian Alphabet documents were first drafted in July 1835, although they provide no evidence to substantiate their assertion.3

[Page 79]On 1 October 1835, Oliver Cowdery wrote the following for Joseph Smith:

October 1, 1835. This after noon labored on the Egyptian alphabet, in company with brsr O Cowdery and W. W. Phelps: The system of astronomy was unfolded.4

In this case, we have three documents, two of which are labeled “Egyptian Alphabet,” and one of which is damaged at the place where the label would be. The titles of the documents match the name mentioned in the journal. These documents are in the handwriting of Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and W. W. Phelps, the three people who were present, according to the Journal. The most reasonable explanation is that the documents are the very ones mentioned in the Journal entry, and the entry allows us to date the documents.

The editors state that “The Egyptian Alphabet documents show changes in ink, scribe, and style of script, which suggests that the documents were created in multiple settings.”5 This assertion is debatable. All the material in Joseph Smith’s hand is in the same ink and style of script. The same is true for the manuscript in Oliver Cowdery’s hand. Phelps’s hand is more erratic in style to begin with.6 This suggests that the bulk of at least two of the manuscripts was created in a single setting.

Other factors, however, suggest the hypothesis that the documents were created at different times is unlikely. The editors note that “similarities in spelling and phonetics among many of the transliterations hint at a shared creation process.”7 The 1 October 1835 journal entry also suggests this. The question that arises from this is — at what other times would Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and W. W. Phelps have gotten together to work on this?

During the 1835‒1836 period, we know of the following instances where Oliver Cowdery wrote dictation from Joseph Smith:

| [Page 80]Date | Scribe | Pages | Reference |

| 16 March 1835 | Oliver Cowdery (copied by Warren Cowdery) | 2 | JSPD4,8 292‒93 |

| 27 April 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD4, 298‒99 |

| 1 June 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD4, 325 |

| 15 June 1835 | Oliver Cowdery (copied by Warren Cowdery) | 2 | JSPD4, 344 |

| 10 August 1835 | Oliver Cowdery (copied by Warren Cowdery) | 1 | JSPD4, 381‒82 |

| 22 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 2 | JSPD4, 429‒30 |

| 22 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 61‒62 |

| 22 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD4, 432‒33 |

| 22 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD4, 433‒34 |

| 22 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 2 | JSPD4, 435‒36 |

| 25 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 64 |

| 26 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 64‒66 |

| 27 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 66 |

| 28 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 66 |

| 29 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 66‒67 |

| 30 September 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 67 |

| 1 October 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 67 |

| 2 October 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPJ1, 67 |

| 21 December 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 2 | JSPD4, 351‒53 |

| 22 December 1835 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD4, 364‒65 |

| 3 March 1836 | Oliver Cowdery (copied by Warren Cowdery) | 4 | JSPD5,9181‒85 |

| 19 March 1836 | Oliver Cowdery (copied by Warren Cowdery) | 1 | JSPD5, 185 |

| 21 March 1836 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD5, 187‒88 |

| 17 August 1836 | Oliver Cowdery | 1 | JSPD5, 280 |

During that same time period, we know of the following instances when W. W. Phelps took dictation from Joseph Smith:

| [Page 81]Date | Scribe | Pages | Reference |

| 1 June 1835 | W. W. Phelps | 2 | JSPD4, 329‒33 |

| 2 June 1835 | W. W. Phelps | 4 | JSPD4, 333‒39 |

| 15 June 1835 | W. W. Phelps | 1 | JSPD4, 346‒47 |

| 6 August 1836 | W. W. Phelps | 3 | JSPD5, 277‒78 |

There were also occasions during 1835–1836 when Joseph Smith wrote for himself:

| Date | Scribe | Pages | Reference |

| 20 July 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPD4, 370‒71 |

| 22 September 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 62 |

| 23 September 1835 | Joseph Smith | 2 | JSPJ1, 62 |

| 24 September 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 64 |

| 19 December 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 135 |

| 20 December 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 135 |

| 21 December 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 135 |

| 22 December 1835 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPJ1, 135 |

| 19 August 1836 | Joseph Smith | 1 | JSPD5, 281‒83 |

Two important points emerge from these listings: the dates of the scribal activity and the maximum number of pages they produced as scribes.

The dates show a range of time when each scribe was active taking dictation from Joseph Smith. Oliver Cowdery took dictation sporadically but served as Joseph Smith’s main scribe from 22 September 1835 to 2 October 1835. The dates show that Phelps worked as Joseph Smith’s scribe only in June 1835 and August 1836. We know he was present and involved only on 1 October 1835 because of Joseph Smith’s journal entry. Since all the records of scribal activity are based on Joseph Smith’s dictation, he was involved in all instances, and the list of times when he wrote for himself are irrelevant for the purpose of establishing his presence. Phelps’s rare involvement as a scribe for Joseph Smith during 1835 and 1836 raises questions about the extent of Joseph Smith’s involvement in material from this time in Phelps’s hand. Based on the ranges of scribal activity, the only other time the scribes were working in close relation to each other was the first part of August 1835.

Knowing the range of pages is also helpful. Both Oliver Cowdery and W. W. Phelps were known to produce documents in the range of one to four pages in length, whereas Joseph Smith wrote documents of only [Page 82]one or two pages. Of course, many of the documents were only one page long and needed to be only a page long. The lower end of the range is not particularly helpful, but the upper end of the range tells us it is well within the capacity of the scribe to produce a document of that length. Furthermore, while the Egyptian Alphabet document in Joseph Smith’s hand is four pages long, Joseph Smith’s handwriting ends on the second page, which is consistent with other documents from the same time in his handwriting.

All of the Egyptian Alphabet documents are within the range of documents being produced in a single session. This is even more likely because most of the pages are unused, and all the documents are unfinished. That no scribe can be considered to have worked on the Egyptian Alphabet documents in more than one session is the most likely possibility. That session occurred on 1 October 1835, and all the documents should be specifically dated to that day, as previous volumes in the Joseph Smith Papers series did.10 The move away from the correct date is baseless and must be considered an error on the part of the editors.

How do we explain the “changes in ink, scribe, and style of script”? Those changes come after the explanations cease, in other words, after most of the documents were written. There is little reason to view the documents as other than essentially the creation of a single session which took place on 1 October 1835, as stated in Joseph Smith’s journal.

The editors claim that “JS [Joseph Smith] and his scribes envisioned them [these documents] less as an academic production meant to be evaluated by scholars of the day and more as a continuation of their spiritual quest to uncover ancient languages.”11 The editors may be correct that the Egyptian Alphabet documents were probably not intended for evaluation by the scholars of the day. The documents were probably internal explorations. Were they seen as a “spiritual quest”? The term Joseph Smith uses for their work is labored, which means “performing hard work.” He did not use the revelatory term unfolded that he used elsewhere in this entry, nor did he use the term translate as in other entries in late 1835. In the Doctrine and Covenants, the verb labor is often used for secular work; even if it may have a spiritual dimension the frequent metaphor is laboring in the vineyard.12 In the nominal form, [Page 83]this is emphasized by the phrases “temporal labors,”13 “labors on the land,”14 and “labor of his hands.”15 In his journals, Joseph Smith refers to “our Labours in the printing buisness,”16 “Laboured in Fathers orchard gathering apples.”17 In discussing conducting Church councils to correct erring saints, he recorded: “Much good will no doubt, result from our labors during the two days in which we were occupied on the business of the Church.”18 A similar usage appears a couple of months later: “after I came home I took up a labour with uncle John and convinced him that he was wrong & he made his confession to my satisfaction; I then went and laboured with President Rigdon and succeded in convincing him also of his error which he confessed to my satisfaction.”19 Sometimes he does use the word labor in a spiritual sense, though this seems to be the minority: “This day Joseph Smith jr. labored with Oliver Cowdery, in obtaining and writing blessings. We were thronged a part of the time with company, so that our labor, in this thing, was hindered.”20 While Joseph Smith could use the term labor for spiritual things, he more often used it for the exertion of physical and mental effort, and there is no particular reason to interpret it necessarily as some “spiritual quest.”21 Joseph Smith’s usage suggests that mental effort is more likely in this context. Those who wrote them were working something out in their own minds.

Document Labeling

The labeling of the documents is misleading. It implies a chronological order: A, then B, then C. The editors claim that “Egyptian Alphabet-C (largely in the handwriting of Phelps) was likely begun first, followed by Egyptian Alphabet-B (in the handwriting of Cowdery),” and that “Egyptian Alphabet-A … was likely begun last,”22 which would imply that their labeling was backwards. In the same paragraph, however, they argue the opposite, saying that “Phelps and Cowdery appear to [Page 84]have expanded on earlier, simpler definitions found in JS’s Egyptian Alphabet-A,”23 which means it predates the other versions. They also argue that “both Phelps and Cowdery inscribed at least parts of their versions as the text was dictated or read aloud.”24 We will deal with these assertions later. At this point, it is enough to note that the labeling of the Egyptian Alphabet documents implies an order and creates confusion.

It would have been simpler, less confusing, more accurate, and without chronological implications if the editors had simply identified the manuscript by the principal handwriting. Thus calling what the editors label “Egyptian Alphabet-A” the “Egyptian Alphabet in Joseph Smith’s handwriting” is clearer because it highlights the most salient difference in the document. Calling it “Egyptian Alphabet-A” implicitly assigns it chronological priority.

If one accepts the editor’s assumption that there is a relative order to the Egyptian Alphabet documents, how does one go about determining the order, and how does one do so without falling into a circular argument by assuming what one sets out to prove?

Evidence of Formatting

The formatting of the Egyptian Alphabet documents is distinctive among all the other documents in the volume in which they are published. Vertical lines are ruled on a number of pages, thus dividing the page into a number of columns.

In the copy of Egyptian Alphabet containing Joseph Smith’s handwriting, the first page is ruled into four columns, while the rest of the pages are not ruled. All four pages of W. W. Phelps’s manuscript are ruled into four columns. In the copy of the Egyptian Alphabet in Oliver Cowdery’s hand, the first page is ruled into five columns. The first column is used as a margin. The second page has two columns, but the rest of the leaves are not ruled.

Only W. W. Phelps labels the columns in the manuscript. On the first page, the columns are labeled “Character,” “lettr,” “Sound,” and “Explanation.” The last of these labels is written on a higher line than the other three. Two of these labels (“character” and “sound”) are continued through the rest of the pages of the manuscript.

The different scribes used the columns differently. Not all the written letters are kept within the confines of the columns. For the first page (which is the only page where all the manuscripts follow the columnar format), this can be tabulated in the following table:

| [Page 85] | W. W. Phelps | Oliver Cowdery | Joseph Smith |

| Sound column flows into following explanation column | 7 out of 36 | 8/36 | 4/37 |

| Explanation column flows into previous sound column | 0/36 | 3/36 | 30/37 |

So W. W. Phelps respects the columns. He ruled all his pages with columns. He labeled them. In seven cases, where the writing in the sound column exceeded the space allotted, the writing extended to the next column, but otherwise he stayed within the columns. In subsequent pages, he adhered to the columnar format less rigidly. Oliver Cowdery did not label the columns and followed the format less rigorously but still followed the format most of the time. Joseph Smith, on the other hand, completely ignored the columns and simply ran the text together. In those cases where the line separating the column happens to separate the sections, it can be argued to be coincidental rather than intentional. In three cases, Joseph Smith did not even write the sound in and had to add it in above the line after the fact.

Based on these considerations, it would appear that the project was the brainchild of W. W. Phelps. Phelps followed the program, while Smith did not. Joseph Smith was not invested in the project, as indicated by way in which he ignored the columnar format and sometimes forgot to include the sound component. Based only on the formatting, we would conclude that Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery were copying Phelps’s work.

Evidence from Scribal Practices

The editors assert that “Phelps and Cowdery appear to have expanded on earlier, simpler definitions found in JS’s Egyptian Alphabet A.”25 This assumption that later scribes expand the text and that the earlier text is always shorter in form, called lectio brevior potior, has been empirically debunked before,26 but can be demonstrated to be false by looking at scribal usage among Joseph Smith’s scribes at exactly the time when the Egyptian Alphabet documents were produced.

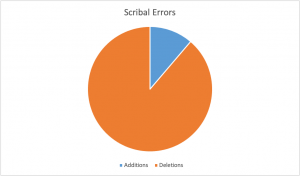

Joseph Smith’s scribes did much more than simply take dictation in 1835, though they did do that. In some cases, they copied entire passages verbatim from sources that we have. This allows us to look at their scribal practice and tendencies. For our purposes, we can look at [Page 86]the amalgam of scribal efforts in copying and the tendencies to expand or contract the text they are copying in 1835‒1836. Since most readers will not be interested in a lengthy list of textual differences, the results will be summarized. There are 63 instances of dropping material from the text they are copying and eight instances of adding material to the text. The scribes (Thomas Burdick, James Mulholland, Warren Parrish, George W. Robinson, Frederick G. Williams) were almost eight times more likely to drop information from the text than to add to it.

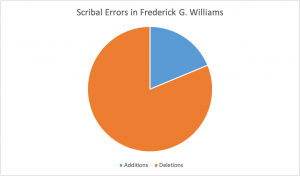

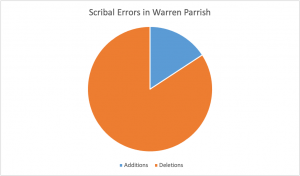

In pie chart form, it looks like what is shown in Figure 1. This pattern extends to individual scribes — Frederick G. Williams (Figure 2) and Warren Parrish (Figure 3). In no case does the number of additions exceed the number of deletions.

Figure 1. Scribal errors.

Figure 2. Frederick G. Williams scribal errors.

[Page 87]

Figure 3. Warren Parrish scribal errors.

Given this documented tendency in Joseph Smith’s scribes from the period when the materials in JSPRT4 were created, we can develop a method to determine whether a document is likely copied from another document. Material from one document not in the other document counts as an expansion in the first document and a contraction in the second. In a comparison of the two documents, the original should have significantly more expansions than contractions, and the copy should have significantly more contractions than expansions. We will consider the cases in the implied chronological order of the publication: Joseph Smith vs. Oliver Cowdery, Joseph Smith vs. W. W. Phelps, and Oliver Cowdery vs. W. W. Phelps.

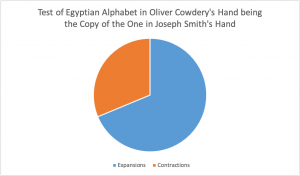

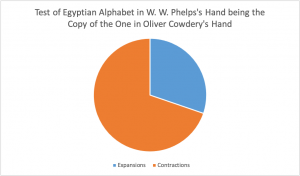

For the sake of argument, we will consider the relationship between the Egyptian Alphabet in Joseph Smith’s hand with the one in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting and assume for the purposes of the test that the document in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting is a copy of the one in Joseph Smith’s handwriting, which is implied in the ordering of the documents in the publication. Comparing the Egyptian Alphabet document in Joseph Smith’s handwriting to the one in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting, we get what is illustrated in Figure 4: the document in Cowdery’s hand has 33 expansions and 15 contractions compared to the one in Joseph Smith’s hand. Our method would indicate that if there is copying, Joseph Smith is copying the Egyptian alphabet in Oliver Cowdery’s hand.

[Page 88]

Figure 4. Test of Egyptian Alphabet in Oliver Cowdery’s hand being the copy of the one in Joseph Smith’s hand.

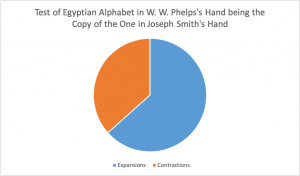

This single test is insufficient. We must also test the Egyptian Alphabet in Joseph Smith’s hand against the document in W. W. Phelps’s hand. Again we will follow the ordering of JSPRT4 and assume that the one in Joseph Smith’s hand is the original and that W. W. Phelps’s is the copy. We get the results illustrated in Figure 5: the document in Phelps’s handwriting has 52 expansions and 30 contractions compared to the one in Joseph Smith’s hand. For our test case, we would have to say the assumption fails the test, which indicates that if there is copying, Joseph Smith is copying the document in W. W. Phelps’s hand.

Figure 5. Test of Egyptian Alphabet in W. W. Phelps’s hand being the copy of the one in Joseph Smith’s hand.

In either case, the Egyptian Alphabet in Joseph Smith’s hand appears to be a copy of the other document. Which of the documents in Oliver Cowdery’s or W. W. Phelps’s hand appears to be the original? We can test those two documents against each other. For this test we will assume, based on the order given in JSPRT4, that Phelps is copying Cowdery. The copy of the Egyptian Alphabet in Phelps’s hand has 13 expansions and [Page 89]30 contractions compared to the one in Cowdery’s hand (see Figure 6). In this case, it does look like Cowdery’s is the original document.

Figure 6. Test of Egyptian Alphabet in W. W. Phelps’s hand being the copy of the one in Oliver Cowdery’s hand.

It is actually doubtful that the Egyptian Alphabet documents were intended to be copies. The expansions in copies made by Joseph Smith’s scribes in 1835‒1836 were all dittographies; that is, they were all repetitions of words and phrases made when the scribe’s eye slipped back to a previous section, whereas none of the expansions in the Egyptian Alphabet documents are dittographies.

So were the documents dictated? The editors claim that “both Phelps and Cowdery inscribed at least parts of their versions as the text was dictated or read aloud.”27 The evidence they provide is that

at character 2.6, it appears that “under or less” was heard and interpreted differently by Phelps and Cowdery. Phelps seems to have begun to write “under,” but then upon hearing “or,” he replaced “under” with “less.” Cowdery, on the other hand, heard “under or less,” and wrote the entire phrase, interpreting the “or” as a clarifying word.28

The full passage of this single instance in context makes their interpretation problematic. The full passages in the various handwritings are as follows (my transcriptions, their order):

Smith: Alc{h}{o\i}beth ministers of God un{d}<e><r> or the less

Cowdery: Alch{o\i}beth Ministers of Go<d>, less, or under th{e} high priests

Phelps: Alch<i>beth Ministers of God, under <less> than high priests

[Page 90]There are multiple problems with the editors’ interpretation. For starters, Cowdery did not write, as they claim, “under or less” but “less, or under”. Phelps wrote “under”, crossed it out, and wrote “less” directly over the second half of the word. It looks as if Smith (1) wrote “und”, (2) retouched the “d”, (3) added an “r”, (4) then went back and wrote the “e”, although steps (2) and (3) might have been in the other order. The manuscript evidence does not back the scenario set forth by the editors, even in their own transcriptions.

Considered alone, the Smith and Phelps manuscripts are explicable as aural errors for the same phrase. Cowdery’s metathesis of the phrase — that is, reversing the order of the words — is less explicable in that way.

This example also shows a problem with the editors’ assertion that “Egyptian Alphabet–A contains the most complete definitions for the final copied character.”29 In this case, the definition in Joseph Smith’s hand is fundamentally incomplete, lacking the final noun phrase. This noun phrase, while it makes sense in the context, is not something that could be filled in based on Smith’s version alone.

Contents

One of the more interesting facets of the Egyptian Alphabet documents is their content, both in terms of the characters they use and the concepts discussed.

In terms of the characters, the various characters labeled “parts” correspond to various columns of Joseph Smith Papyrus I, as shown in the following table:

| Papyrus column (from right to left) |

Label in the Egyptian Alphabet |

| Joseph Smith Papyrus I column 1 | Fourth part of the first degree |

| Joseph Smith Papyrus I column 2 | Third part of the first degree |

| Joseph Smith Papyrus I column 3 | Second part of the first degree |

| Joseph Smith Papyrus I inscription over the vignette | First degree |

| Joseph Smith Papyrus I column 4 | Fifth part of the first degree |

Matching the characters from the papyrus with the characters copied into the Egyptian Alphabet documents clarifies the terminology used in the Egyptian Alphabet documents. There the term part is used for what we call the column of the papyrus. It is a term that refers to [Page 91]location. The term degree refers to what we would call a fragment. The usage in the Egyptian Alphabet differs from that of the Book of Abraham manuscripts. In the Egyptian Alphabet documents part precedes degree. In the Book of Abraham manuscripts degree precedes part, as in “fifth degree of the Second part.”30 The characters in the Book of Abraham manuscripts come from a number of different lines from Joseph Smith Papyrus XI, so the usage there cannot be the same as in the Egyptian Alphabet documents, as it no longer refers to the location of the character in the papyri (i.e., the reference to “fifth degree” in two of the Book of Abraham manuscripts does not seem to comply with the concept of “degree” in the Egyptian Alphabet). In the Book of Abraham manuscripts, all characters, regardless of which line they come from, have the same designation as to degree or part. The usage in the Grammar and Alphabet differs dramatically, since there the term degree has transformed into a method of interpretation of characters.31 This is an indication of different minds using the same terminology.

It is also clear from this correspondence that the Egyptian Alphabet project took the columns in left to right order. This also extends to the reading of characters within the columns: the character on the left is given before the character on the right.32 In the Book of Abraham manuscripts, the characters are read in the other direction, from right to left.

Joseph Smith Papyrus I, in its current state, has the remains of an inscription over the vignette. Only traces of the last three signs remain, but the state of preservation seems to have been better in October of 1835, when they were copied into the Egyptian Alphabet. In theory, the characters listed under the (first part of the) first degree could be reassembled to reconstruct the now missing inscription, but such a reconstruction would not be easy, since it is not a trivial matter to recognize the Egyptian glyphs as they have been copied by scribes who were unskilled at copying them. This may suggest that if the inscription [Page 92]here were more complete in 1835, then the vignette itself was likely more intact than at present.

It is also theoretically possible to reconstruct the titles of the mother of the ancient owner of Joseph Smith Papyrus I, though this is not currently possible, given the way that the glyphs were copied in the nineteenth century. Readers should recall that the glyphs in the first three columns of Joseph Smith Papyrus I were not correctly read by the first generation of scholars who had access to the actual photographs.

In terms of concepts, many of the definitions given parallel Abraham 1:24‒25, 31. Consider the following set of parallels emphasized here:33

| Egyptian Alphabet — Oliver Cowdery handwriting | Book of Abraham |

| The land of Egypt first discovered under water by a woman | When this woman discovered the land it was under water, who afterward settled her sons in it; and thus, from Ham, sprang that race which preserved the curse in the land. (Abraham 1:24) |

| What other person is that? Who. | |

| Reign, government, power, kingdom, or dominion34 | Now the first government of Egypt was established by Pharaoh, the eldest son of Egyptus, the daughter of Ham, and it was after the manner of the government of Ham, which was patriarchal. (Abraham 1:25) |

| The beginning, first, before, or pointing to | |

| In the beginning of the earth, or creation | But the records of the fathers, even the patriarchs, concerning the right of Priesthood, the Lord my God preserved in mine own hands; therefore a knowledge of the beginning of the creation, and also of the planets, and of the stars, as they were made known unto the fathers, have I kept even unto this day, and I shall endeavor to write some of these things upon this record, for the benefit of my posterity that shall come after me. (Abraham 1:31) |

It is clear that the Egyptian Alphabet document depends on the text of the Book of Abraham, but the Book of Abraham is not derivative of the Egyptian Alphabet document. Too much has to be supplied to claim [Page 93]that the Book of Abraham is derived from the scattered concepts of the Egyptian Alphabet. Had it been that obvious, the editors would have pointed out the connections, but they did not notice them. On the other hand, it is much easier to derive the concepts of the Egyptian Alphabet from the Book of Abraham. This indicates that the translation of the Book of Abraham had already reached Abraham 1:31 before 1 October 1835.

Did the scribes really think this was a translation project? If the scribes of the Egyptian Alphabet really thought that the characters from Joseph Smith Papyrus I were translated by the concepts listed in the Egyptian Alphabet documents, wouldn’t the concepts come together to form some sort of coherent narrative? Why did they spend all that time connecting Joseph Smith Papyrus I with the text from the Book of Abraham and yet match up the translation of the Book of Abraham with characters taken from Joseph Smith Papyrus XI? Here it is significant that Joseph Smith used the expression labored on rather than translated; he did not seem to regard the work that he did on those documents as translation.

The Theory of the Editors

As has been demonstrated, the evidence from the manuscripts indicates that the Egyptian Alphabet did not originate with Joseph Smith, who was generally copying the other two manuscripts. This is not the way the editors portray it in the footnotes and the introduction to the section:

“JS and some of his associates began creating three Egyptian Alphabet documents.”35

“Phelps likely began inscribing Grammar and Alphabet material in this volume sometime between July 1835 (when the Egyptian Alphabet documents were first drafted) and 1 October 1835 (when JS’s journal mentions that JS, Oliver Cowdery, and William W. Phelps worked on “the Egyptian alphabet,” which could refer either to the Grammar and Alphabet volume or to the Egyptian Alphabet documents).”36

“Phelps and Cowdery inscribed at least parts of their versions as the text was dictated or read aloud.”37

[Page 94]“Phelps and Cowdery appear to have expanded on earlier, simpler definitions found in JS’s Egyptian Alphabet-A”38

“The evolving use (or disuse) of columns and the varying page size both suggest that JS’s plans for presenting the information in the document changed as he worked.”39

“JS and his clerks abandoned this project, moving on to work on the Grammar and Alphabet volume.”40

“The Grammar and Alphabet volume, for example, adopts and further develops the structure found in the Egyptian Alphabet documents.”41

“The Grammar and Alphabet volume was one piece of a larger attempt to understand the Egyptian language, which was in turn part of a larger effort by JS to study ancient languages.”42

The editors present the whole project as Joseph Smith’s, but the manuscript evidence indicates that the conception of the project belonged to Phelps, while the fullest definitions are generally those of Cowdery.

Theories of Translation

There are three basic theories about the original source text from which the Book of Abraham was translated. One is that Joseph Smith translated the text of the Book of Abraham from the papyri fragments we now have. Few members of the Church believe this theory, but it is pushed by anti-Mormons. The second theory is that Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham from papyri that we do not currently possess. The third theory is that Joseph Smith received the Book of Abraham directly through revelation without possessing a text that contained the ancient text of the Book of Abraham. The Church accommodates either of the latter two theories. Presumably, the Joseph Smith Papers Project would be fine with either of the latter two options.

How do the various documents in JSPRT4 fit into the various translation scenarios? We will consider these individually, starting with the theory that Joseph Smith received the Book of Abraham without [Page 95]possessing the text of the Book of Abraham. Under this theory, since Joseph Smith received the Book of Abraham directly by inspiration, there was no connection between the Book of Abraham and the papyri. At best the papyrus served as a catalyst for Joseph Smith to get revelation, but once he started receiving the Book of Abraham by revelation, he presumably did not need the papyrus anymore, since he would have been receiving the revelation as he did for sections of the Doctrine and Covenants. If one wishes to consider the production of the Egyptian Alphabet in October 1835 as the initial jumpstart of the project,43 then there was no reason for Joseph Smith to pursue the project further. Under the direct-inspiration scenario, Joseph Smith would have no logical reason to be involved in the production of the further Grammar and Alphabet documents. Those documents would be seen as the work of W. W. Phelps during times when he was not serving as a scribe to Joseph Smith.

In the theory that Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham from papyri that we no longer have, the Book of Abraham is connected with specific papyri, but papyri which we no longer have access to. The Egyptian Alphabet documents thus serve as an effort by Phelps and Cowdery to match the translation with the characters from papyri in their possession. As we have seen, the manuscript evidence actually supports this interpretation. The Grammar and Alphabet documents are seen as the work of Phelps, done at a time period (August 1835 to July 1836) when he was not serving as Joseph Smith’s scribe. These documents would not then be the work of Joseph Smith, and thus are irrelevant to understanding the translation of the Book of Abraham.

Only if one assumes that Joseph Smith tried to translate the Book of Abraham from papyri that have survived does the program propounded by the editors make any kind of sense. Although attributing the Grammar and Alphabet to Joseph Smith is not required for Joseph Smith to have translated the Book of Abraham from the current papyri, adopting this theory makes it easier to argue for this option. This scenario is pushed by critics of the Church, and not many members of the Church believe it.

Assigning the Grammar and Alphabet to Joseph Smith (for which, incidentally, there is absolutely no evidence) undercuts the direct [Page 96]inspiration scenario. It also does not work well with the scenario that Joseph Smith translated the Book of Abraham from different papyri.

As we have seen, the editors of the documents promote a historical scenario in which Joseph Smith decided to produce an Egyptian Alphabet, and used it to produce the Book of Abraham. This is the scenario promoted by critics of the Church. Other possibilities, including the two theories most commonly held by members of the Church, are ignored.

Results

The Egyptian Alphabet documents seem to be evidence that Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and W. W. Phelps studied things out in their mind. There seems to be an attempt, for unknown reasons, to match concepts from Abraham 1:24‒25, and 31 with characters from Joseph Smith Papyrus I. Their incomplete nature is indicative of the stupor of thought that came with this otherwise unproductive line of inquiry. The last English words that Oliver Cowdery writes before giving up the “Sound” column are parenthetical comments after three sounds (perhaps glosses) listing words for “the earth &c,” “Moon,” and “Sun” before ending anything other than copying of characters,44 which may have been done previously. Joseph Smith describes the process as they “labored on the Egyptian alphabet,” and then “the system of astronomy was unfolded” to them. In the other two manuscripts the last word written is “Kolob,” which is prominently associated with the astronomical portion of the Book of Abraham, occurring both in the Explanation to Facsimile 2 (Figures 1 and 2), and in Abraham 3:3‒4, 9, 16. The editors argue that this word (Kolob) is a later addition,45 but even if the argument is correct, Cowdery’s manuscript shows that the project stopped when the topic shifted to astronomy. They stopped the Egyptian alphabet project once revelation came, and neither Joseph Smith nor Oliver Cowdery seems to have ever picked it up again.

The system of astronomy might refer to (1) the explanation of Facsimile 2, or (2) the astronomical portion of the Book of Abraham in chapter 3, or (3) the “knowledge of the beginning of the creation, and also of the planets, and of the stars, as they were made known unto the fathers,” promised at the end of the first chapter (Abraham 1:31), which would have come after the creation narrative in Abraham chapter 5. There is evidence that the third option was the one referred to. On [Page 97]16 December 1835, Joseph Smith was explaining “many things to them concerning the dealings of God with the ancient<s> and the formation of the planetary system,”46 which was understood as “the system of astronomy as taught by Abraham.”47 On 6 May 1838, Joseph Smith gave a discourse wherein “He also instructed the Church, in the mistories of the Kingdom of God; giving them a history of the Plannets&c. and of Abrahams writings upon the Plannettary System &c.”48 A system of astronomy taught by Abraham that includes the formation of the planetary system or history of the planets is arguably not in the current Book of Abraham or any of the manuscripts but does match the description of what Abraham promises to write at the end of the first chapter. It is also possible that the first and third options are the same. None of these three things are in manuscripts from the Kirtland period. Whichever of the three options it was, however we choose to understand it, the revelation on astronomy from 1 October 1835 was beyond the translation of the Book of Abraham as evidenced in the preserved manuscripts from the Kirtland period.

Such insights may be obtained by careful study of the documents if one does not subscribe, as the editors do, to anti-Mormon theories about the production of the Book of Abraham. The evidence of editorial bias in JSPRT4 is demonstrable, pervasive, and systemic. This bias opposes the interests of the Joseph Smith Papers institutional sponsors, the beliefs of most members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and (most importantly) the evidence of the manuscripts being published.

Go here to see the 5 thoughts on ““Prolegomena to a Study of the Egyptian Alphabet Documents in the Joseph Smith Papers”” or to comment on it.