Abstract: It is natural to wonder how the day on which Jesus was crucified could come to be known as Good Friday. In this exploration of the topic, John Welch examines the many events which occurred on that fateful day and the meaning they have for us today.

[Editor’s Note: This article is based on a talk delivered on Good Friday, April 2, 2021, to the German Missions Reunion in Salt Lake City. It has been lightly edited for publication.]

Today happens to be an auspicious day, Good Friday, the Friday before Easter Sunday. It is a suitable time to reflect on the trial, the cross, and the death of Jesus.

Karfreitag is the German name for Good Friday. The word kar means klage (mourning), kummer (worry), and trauer (sorrow). For Catholics it is a solemn day of fasting, which traditionally means that people eat fish on that day, but it also means they avoid alcohol, even beer. In Germany, this day is also known as Stiller Freitag (quiet Friday). Some German states restrict it as a day of silence, when certain types of noisy activities, such as concerts or dances, are legally banned. This name echoes the “Stille Nacht” (Silent Night) of Jesus’s birth 33 years earlier, but now that word draws our attention to Jesus’s voluntarily stilling his mortal body, even as he once stilled the storm on the Sea of Galilee.

Consider for a few moments all that happened during those particular 24 hours of that day. On the Jewish calendar, as one should note, the day began when the sun went down the evening before. So Good Friday actually began with the Last Supper, with the Lord’s beautiful [Page 2]words in John 13–17, and continued with the Lord’s cosmic conflict in Gethsemane and then with Judas’s betrayal and Jesus’s arrest. All that then led to Golgotha, to the cross, to his yielding up of his spirit, to the earthquakes, to placing Jesus’s body in the tomb, and to his breaking down the gates of Hell. All of that was accomplished within those 24 fateful and fruitful hours. It was indeed a terribly Good Friday!

Although many things happened that day, and all of them were crucially important, in most Christian minds, attention focuses primarily on the Cross. As you will remember, in Germany depictions of the crucifixion were almost everywhere — on monuments, on shrines beside most country roads, and on the tops of alpine peaks. Sometimes, as in the Catholic style, the depiction was of the dead, crucified body of Christ on the cross. Other times it was in the plain Protestant mode of showing the empty cross, which emphasizes that his body is no longer here, for he is risen.

Seeing all these kinds of crosses in Germany made a deep impression on me as a young missionary in the 1960s in Bayern, in Bamberg and Berchtesgaden. I learned there to revere the unpleasantries of the cross as a part of my Latter-day Saint faith.

I have come to appreciate that, as Latter-day Saints, we, of all people, don’t need to choose theologically between Gethsemane or Golgotha. We don’t need to opt between Jesus’s bleeding from every pore, or his bleeding from the wounds in his hands, feet, and side. I like to think of it this way: Jesus overcame spiritual death in the darkness of Gethsemane, while he vanquished physical death in broad daylight on the cross. Both, working together, were necessary.

People sometimes wonder why Latter-day Saints don’t usually wear crosses, as many Christians do. Might a good answer be that, while we don’t outwardly wear crosses, we do bear holy marks of the crucifixion in the tokens of our temple covenants? By keeping those covenants, we inwardly reverence the cross and strive to always remember Christ crucified.

While teaching, in law-school courses at Brigham Young University in Provo, for 40 years various topics on Jewish, Greek, and Roman laws in the New Testament, many things have impressed me about the trials and execution of Jesus. Above all, I have found a pervasive need for humility and caution. As Elder Bruce R. McConkie stated, “No revelation tells us all that happened there” — all of which is very difficult to understand from a legal perspective. Discussing this topic with Jewish and Christian scholars, I have learned to be aware that law in that day was very different [Page 3]from ours today. For example, it was common for multiple charges to be thrown simultaneously at a defendant. There was no “code pleading.” No indictment was given with specific allegations. Defendants were not always sure exactly what they were being accused of. Indeed, Jesus was accused of many things. Yet there was no general right to confront one’s accusers — unless you were a Roman citizen. And remaining silent could be held against you.

In addition to problems in knowing what the law required, I have also found that many of the facts in Jesus’s case are difficult to tie down. One must live with many uncertainties and contradictory details even in the accounts of the four Gospels. Did the disciples escape from the Garden? Or did Jesus negotiate for their release? Were there two meetings of the Sanhedrin? Or just one?1 What was the relationship between the Sanhedrin and the Romans in Jesus’s day? In many such cases, we just don’t have enough historical information to know as much as we would like to know.

Moreover, I have found it helpful for readers to realize that each of the four Gospels, for its own purposes, takes its own approach and emphasizes different elements of these complicated events. Matthew highlights Israelite and Jewish features. Luke is more Greek and populist. John takes an eternal perspective.2 But, most importantly, all four accounts are good; regarding the ultimate outcome — that Jesus really died and really rose from the dead — all four Gospels are in perfect agreement.

Most recently, I have become especially intrigued with the rarely mentioned legal problems that must have grown out of the raising of Lazarus (Figure 1) and the full trial found already at the end of John 11. Jesus performed that miracle a month or so before Good Friday.

[Page 4]

Figure 1. A third-century glass plate in the Vatican Museum shows Jesus miraculously raising Lazarus and bringing him forth out of the tomb.

(Photograph by John W. Welch.)

By knowing that Jesus had already been convicted by Caiaphas in John 11, one can make much better sense of what happens in John 18. In pronouncing the verdict in that trial in John 11, Caiaphas invoked the ancient biblical legal principle that it was “better that one should die” than a whole village or city should be destroyed — the ancient Israelite legal maxim of “the one for the many.” Notice also that an official warrant for Jesus’s capture and execution was then already sent out at the end of John 11, and thus, except for his popularity among the crowd, Jesus could and would have been legally apprehended even during his triumphal entry into Jerusalem.

I find it even more fascinating that another arrest warrant was also sought at the beginning of John 12 for the arrest of Lazarus! Presumably, they saw him as an accomplice in some kind of trick or deception, or maybe they were using Lazarus as bait to see who might come to his defense. In any event, I wonder if Jesus then returned to Jerusalem precisely in order to save the life of his now-threatened friend Lazarus.

[Page 5]All of this legal action in John 11–12 explains what otherwise appears to be a great disregard of legal formalities after Jesus’s arrest in Gethsemane. But if Jesus had already been convicted in connection with the Lazarus incident, legally all that needed to be done in John 18 was to capture Jesus and determine the way he was to be put to death and who should carry out his execution.

Of course, we all recognize that only John’s record includes the material about Lazarus, but many historians and legal scholars have recently come to regard the Gospel of John much more highly than has been the case in previous generations. After all, John was an eyewitness. He was the only disciple present at both the final sentencing before Caiaphas, as well as at the cross. I like John and his accounts for many reasons. After all, as Latter-day Saints like to see things, he was a member of the original First Presidency, with Peter and James.

Next, amid all of this, I have come to realize how everything in Jerusalem had become a theater of fear.3 The scriptures tell us that Caiaphas, Herod Antipas, and even the righteous Joseph of Arimathea were all scared. Why? They all had their reasons. Caiaphas and his chief priests feared Roman reprisals, they also feared Jesus, as well as rioting by the people. Likewise, Pilate and his soldiers feared Tiberias, who was a known hypochondriac about disloyalty of his officials.

In addition, most of the Apostles had to run for cover. The early apocryphal Gospel of Peter reads, “We hid ourselves, for we were sought for by them as malefactors.”4 That is the word used to describe the other two men crucified alongside Jesus, so this source tells us that Peter and the Apostles might have been the next targets and victims.

The women, too, and just about everyone were all terrified, as the earliest copies of the Gospel of Mark famously and abruptly end, “And they went out quickly, and fled from the sepulchre; for they trembled and were amazed: neither said they any thing to any man; for they were afraid” (ephobounto, Mark 16:8).

In that world, as I have come to understand and we can understand as we have come to fear the invisible anthrax or COVID, what people feared most were forces beyond their control, like the weather — what [Page 6]caused it to rain or not to rain, fearfully causing famines? Most of all, they all feared the supernatural. Angels who came even needed to say, “Fear not! Don’t be scared!”

The common reaction by people to Jesus’s miracles was fear — if Jesus could still the storm and raise the dead, what else could he do? How about cause an earthquake to destroy the temple? If Jesus was almost killed in Galilee for driving out evil spirits, supposedly by the power of Beelzebub, how much more problematic must have been his raising of Lazarus just over the hill from the temple in Jerusalem?

When people are afraid, they act desperately and even irrationally. Being irrational, it is no wonder it is hard to make rational sense of much of what happened on Good Friday.

Above all, what makes the most sense of all of this is a crucial law found in Deuteronomy 13. That law made it a capital offense to give occult “signs” or to work wondrous “miracles” in order to lead people to follow some other god or to observe some other religious practices. This famous text in Deuteronomy was the basis of the main legal cause of action against Jesus in John 11, and it carried the death penalty.

Seeing all these events in this light, I think we can understand why Caiaphas and the chief priests moved very expeditiously and deliberately in this case. They decided to arrest Jesus in his garden retreat, outside the city, and at night when sorcerers or wonder-workers usually worked their black arts. To any outsider, Jesus would have appeared to be a wonder-worker or, in other words, some kind of a sorcerer.

Making matters more precarious, attempting the arrest at night would have made Jesus very hard for the soldiers to identify. Most of them would have never seen Jesus up close. Hence the need for Judas to positively identify him.

He was probably taken up the stairs to Caiaphas’s palace, which can still be visited today. None of this could have been done without the Romans being aware, since the Garden of Gethsemane is in plain sight, right below the watchtowers of the Roman Antonia Fortress.

Indeed, I think that Caiaphas must have already made an appointment with Pilate to bring Jesus to him first thing after daybreak. No one would have brought such an important case to a Roman ruler — the Prefect of the Roman province of Judea — without putting him on notice and being granted such an early morning audience.

At this point, when Pilate asks the chief priests, “What legal cause of action do you have against this man,” they answer, “We would not have brought him here, except that he was doing kakon,” or, as other ancient [Page 7]manuscripts read, “except that he is a kakopoios.” This word in John 18:30 is especially interesting. It does not just mean a bad guy (kakon) in general, but quite specifically an evil worker or, in other words, a magician (literally, a kakopoios).5

This was a brilliant move by Caiaphas, for the Romans couldn’t have cared less if Jesus had committed blasphemy under Jewish law. But being a wonder-worker who led people into apostasy was not only a capital offense, as in Deuteronomy 13 and thus under Jewish law, but it was also a capital offense under Roman law. Practicing “maleficium” (in Latin) or being a kakopoios (in Greek) was also a serious capital offense under Roman law. Roman law states, “Those who know about the magic art shall be punished with the highest penalty; they shall be thrown to the beasts or be crucified.”6 So, here’s the clincher — under both Jewish law and Roman law, the main punishment for witchcraft, or anything like it, was crucifixion.7

Evidence that Jesus, in fact, was seen as a miracle worker is found in the writings of the historian Josephus. He states that Jesus performed “mighty, wondrous miracles” through some invisible power, merely by his word and his command.8

The Babylonian Talmud contains this fascinating passage:

On the even of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, “He is going forth to be stoned because has practised sorcery and enticed Israel to apostacy [remember Deuteronomy 13]. Any one who can say anything in his favour, let him come forward and plead on his behalf.”9 But since nothing was [Page 8]brought forward in his favour he was hanged [on the cross; crucified] on the even of the Passover!10

This must have been done with Roman approval, if not complicity. Fortunately, we know how the Good Friday story ends. We call it the Victory of the Cross.

When there was no question that Jesus was dead, His body was placed in a tomb. During the night the stone that the guards had placed there rolled aside. In the morning, the tomb was empty. Jeannie and I have stood in this empty tomb on several occasions over the years, as have many people. They, as we, can solemnly and surely testify that he did not die in vain, but rose and truly lives.

Meanwhile, according to Matthew, the chief priests bribed the guards to say that Jesus’s body had been stolen by the disciples, and the chief priests promised the guards judicial immunity if they would say just that (Matthew 28:12–15). Money deals were apparently of special interest to Matthew, a Levite and an erstwhile tax collector.

The analysis does not, and must not, end at that point. Many more people must be seen as being responsible for Jesus’s death in one way or another: Caiaphas, Pilate, Judas Iscariot, the chief priests, Herod Antipas, the Elders, a few noisy Jewish opponents, and various scribes, Pharisees, and Sadducees. Even Peter was left having to deny knowing Jesus. In effect, everyone — or, as Nephi prophesied in 1 Nephi 19:9, the whole “world” — would kill their God. Indeed, it took everyone. And if everyone was and is responsible, then, in an important sense, no one in particular is blameworthy. What a great act of mercy it then is that no one has to go through eternity blaming themselves for having been the one who “done it.”11

For this reason, Peter told the Jews gathered on Pentecost, “I [know] that through ignorance ye did it, as did also your rulers” (Acts 3:17). They all acted in ignorance; they did not know the essential truth about Jesus. Thus, Jesus himself had said from the cross, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

And, as the earliest Christians in Jerusalem chanted “with one accord,” even Herod, Pilate, the Gentiles, and those Jews were merely [Page 9]acting as agents doing, as had been “determined before” in God’s premortal counsel, what “had to be done” (Acts 4:24, 27–28; see also Acts 2:23).

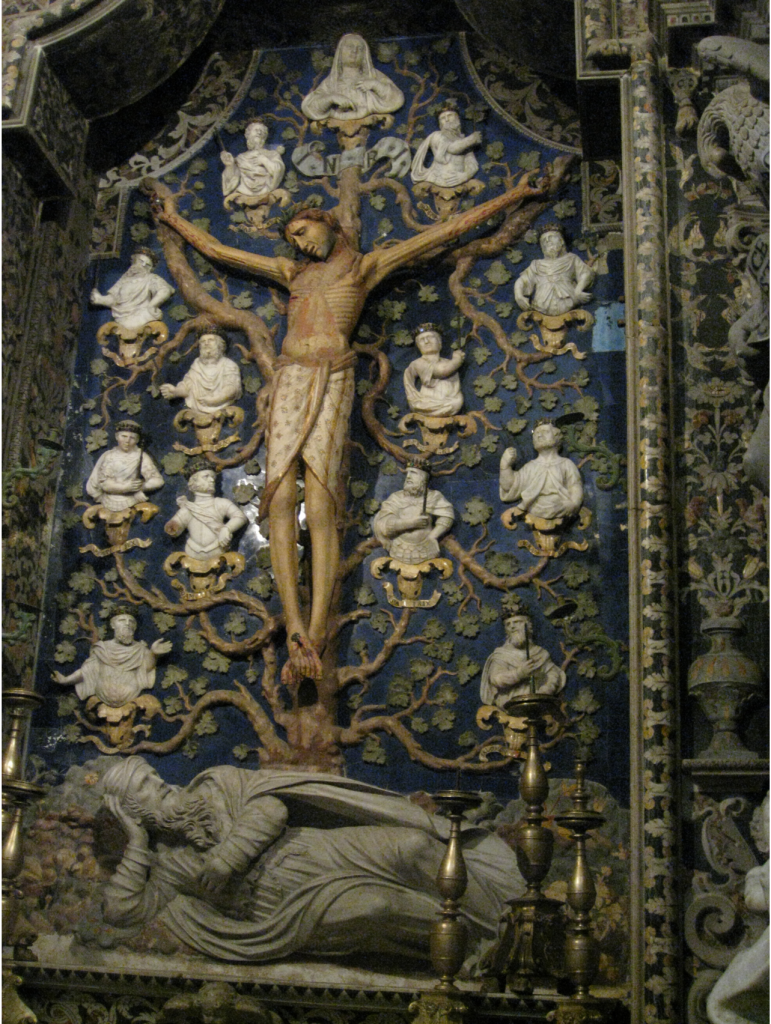

Indeed, the series of events on Good Friday was no mistake. God was not surprised. In fact, it was foreseen by Isaiah, who saw the planting of an eternal tree, a tree of life, that would spring from the stem of Jesse (Isaiah 11). This great tree of life was the Lord Jesus Christ, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Depiction of the stem of Jesse as the tree of life in the Monreale Cathedral, Sicily.

(Photograph by John W. Welch.)

[Page 10]The crucifixion scene on Good Friday was also foreseen by David in Psalm 22. Indeed, as David foresaw the crucifixion scene, Jesus cried out, “My God, my god, why hast thou forsaken me?” This is the opening line of Psalm 22, but there’s more. It goes on: “They pierced my hands and my feet.” “They part my garments.”12 And, when Jesus cried, God “heard.” In the end, as this Psalm foretells, it turns out well, for “the kingdom is the Lord’s and he is the governor.” So Psalm 22 ends victoriously. In the end, Jesus was not abandoned or completely forsaken by God, but only for a time, as was necessary.

All of this took on special meaning to me, as you can now appreciate, when I was refocusing, for other purposes, on the words in King Benjamin’s speech, where he was told by the angel in 124 bc about the Lord God Omnipotent, how “He shall go forth amongst men, working mighty miracles, … raising the dead [such as Lazarus], causing the lame to walk … and even after all this they shall consider him a man, and say that he hath a devil [that’s how they will explain how he is doing his miracles], and [because they will see this as using signs and wonders to lead people astray they] shall scourge him, and shall crucify him” (Mosiah 3:5, 9).

What better prediction and more precise legal explanation of Good Friday could we in this world ever hope for?

Probably the most dramatic exception to the dominance of crucifixion scenes in European cathedrals is Thorvaldsen’s Christus, which dominates the Copenhagen Cathedral in Denmark. Emerging here out of the pillared temple (Figure 3) and the heavenly golden presence of God is not the dying Jesus, but the resurrected, glorified, and living Jesus Christ.

Having suffered, he still bears in his hands and feet the prints of the nails and of the sword in his side. His outstretched arms personally invite us into his love, as shown in Figure 4. He is both the victor over the agony in Gethsemane and the submissive crucified son of the Eternal Father, having descended below all things, so that he could rise above and be in and through all things.

[Page 11]

Figure 3. Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Christus, in the Church of Our Lady, Copenhagen.

(Photograph by John W. Welch.)

Figure 4. Detail of Thorvaldsen’s Christus showing outstretched arms.

(Photograph by John W. Welch.)

In conclusion, I am very grateful that my experiences in Germany taught me and can teach all of us to stop and honor Good Friday. For centuries, its mystery has been celebrated passionately in Oberammergau. [Page 12]One Friday (our Diversion Day, or D-Day, as we called it), on an outing to the town of Altöting, some of us carried heavy wooden crosses around that pilgrimage destination or wallfahrtsort. While I’m afraid it was too heavy a matter for our young minds to take seriously then, that experience made me reflect and ponder. I love what Bavaria then taught me, that Good Friday was not all bad. Good Friday was supposed to happen; it had to happen. Jesus was not victim; he was in full control. His highly unlikely but explicit prophecies that someone would actually crucify him (Matthew 20:19; 26:2) actually came to pass.

Just as he returned to die for his dear friend Lazarus, he himself died, the one for the many (Matthew 20:28; John 11:50; Hebrews 9:28), for his friends, for his people, for each of us, and for all of mankind. As John again articulated it so memorably, “For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved” (John 3:17).

And so, let us see the cross as a tree of life, not a tree of death. It reaches down to the depths to defeat death and to open the tombs of the dead. And as it raised Jesus up, it thereby also lifts us up unto eternal life.

Go here to see the 4 thoughts on ““The Goodness of the Cross and Good Friday: Lessons from Bavaria”” or to comment on it.