Intro/FAQ ⎜ Episode 1 ⎜ Episode 2 ⎜ Episode 3 ⎜ Episode 4 ⎜ Episode 5 ⎜ Episode 6 ⎜ Episode 7 ⎜ Episode 8 ⎜ Episode 9 ⎜ Episode 10 ⎜ Episode 11 ⎜ Episode 12 ⎜ Episode 13 ⎜ Episode 14 ⎜ Episode 15 ⎜ Episode 16 ⎜ Episode 17 ⎜ Episode 18 ⎜ Episode 19 ⎜ Episode 20 ⎜ Episode 21 ⎜ Episode 22 ⎜ Episode 23

[Editor’s Note: This is the twenty-first in a series of 23 essays summarizing and evaluating Book of Mormon-related evidence from a Bayesian statistical perspective. See the FAQ at the end of the introductory episode for details on methodology.]

The TLDR

It seems unlikely that the Book of Mormon could have so many names that can be traced to ancient Semitic and Egyptian, and for those ancient meanings to form wordplays and other connections with the text itself.

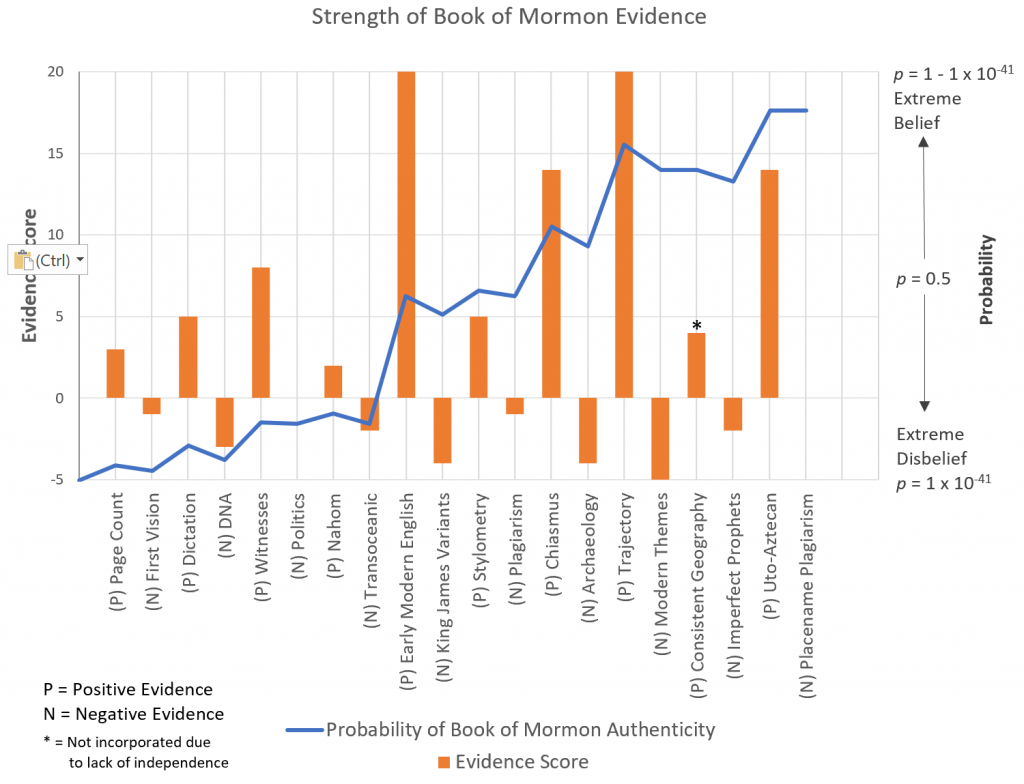

There’s been a substantial amount of faithful scholarship looking at the dozens of unique personal and geographic names in the Book of Mormon, scholarship that purports to find a large number of interesting connections with Semitic and Egyptian languages. Many of these connections also seem to fit well with the text, creating a number of interesting wordplays. The critics, for their part, find reason to fault those names, asking why those connections lack a consistent linguistic framework and why those names seem to lack connections to Mesoamerican languages. After taking a hard look at the names listed in the Book of Mormon Onomasticon database, I conclude that some of that evidence is unexpected, especially the fact that Jaredite names differ systematically from other names in the text, and that the set of identified wordplays appears to exceed what would be likely based on chance. After taking into account the objections of the critics, the Onomasticon represents somewhat informative evidence in the book’s favor, but not overwhelmingly so.

Evidence Score = 4 (increases the likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon by four orders of magnitude)

The Narrative

When last we left you, our decreasingly ardent skeptic, you had just set aside dreams of forging your own plagiarized geography for the book that still lay in your hands, and it takes you a moment to again find your place after that brief distraction. When you again rejoin the narrative, you find yourself somewhat disheartened by the beginning of yet another war. You’d hoped that it’d take more than three pages before the next major conflict flared up, but you’re once again disappointed. This war took a slightly different form, at least—a civil war over succession to the throne, rather than the usual race-driven tribal conflict, though the latter ends up happening anyway.

The monotony of war interests you somewhat less than the interesting names that keep coming up. The late leader, Pahoran, had three sons competing for his vacant seat: Pahoran, Pacumeni, and Paanchi. There was an authentic and exotic quality to those names, and despite your misgivings about the plot, you can’t help but be impressed with the creativity on display in such things—not just here, but in many other places in the book. It couldn’t have been easy to just pull such names out of thin air. And the more an author did so, the greater the risk to which he would be exposing himself. This book professed to be an authentic history of ancient peoples, and you were well aware that cultures generally had rather consistent naming conventions, that those names had meaning to them, and those meanings were used in rhetorical ways to help emphasize their storytelling.

There was a lot of ways that the original names in the book could run afoul of those conventions. If it did, that would certainly be a source of embarrassment for the author. But if it didn’t—well, that would be a different story. It seems unlikely that someone could create so many original names, let alone to have them align with ancient naming practices and, potentially, for those names to be meaningful in the book’s own context.

The Introduction

A long line of faithful scholars, from Nibley to Hoskisson to, mostly recently, Bowen, have spent a great deal of time examining the Book of Mormon’s unique names, whether it be the 188 personal names not found in the Bible (e.g. Corihor, Teancum), or the many other unique geographical names (e.g., Manti, Zarahemla, Jershon). These efforts have yielded dozens of plausible Semitic and Egyptian etymological connections and dozens of meaningful wordplays that suggest that these names were far from random selections from Joseph’s brain. Though the faithful have found these connections interesting and thought provoking, it’s unclear just how well they may serve as evidence for the book’s authenticity. Critics have found these proposals unpersuasive, which itself is unsurprising. But how many of those criticisms have real bite to them? Is it possible that the nature of these names could work against the Book of Mormon? Hopefully Bayes can help us sort through some of these issues.

The Analysis

The Evidence

I’m supremely grateful for the efforts of the good people who maintain the Book of Mormon Onomasticon, a wiki-style database that tracks every non-English (or non-French) word in the book, exploring a number of potential ways that those words connect to different near-Eastern languages. That database has made what would otherwise be an impossible task into one that was merely time-consuming. It meant that my job was to wade through those hundreds of entries in an attempt to better understand those words.

But first, it’s helpful to get a sense of what it is about those words and their potential ancient connections that faithful scholars find compelling. For a helpful summary, we can turn to this video from Book of Mormon Central. They divide the onomastic evidence into five parts:

- Antiquity. Most of the Book of Mormon’s unique names can be plausibly traced to one or more near-eastern languages. Many of the names in the book are obviously biblical (e.g., references to Mary), and many are close variations of biblical names. But even those that aren’t generally fit well in an ancient context.

- Wordplays. Beyond those words’ potentially ancient origins, the ancient meanings behind a substantial number of those words are often meaningfully employed in the text. The usual example is wordplay using the name Nephi in 1 and 2 Nephi, where the Egyptian meaning of “good” plays well with references to things like “goodly parents” and of the “goodness of God.” There are also a number of cases where the names themselves seem meaningful even in the absence of specific wordplay, such as “Gadianton” plausibly meaning “robber band,” and Zeezrom, who gave a large bribe of silver to Amulek, possibly meaning "he of silver." The same also applies to how some of the book’s biblical names are employed in the text.

- Consistencies. The book’s unique names have a number of consistencies that align with what would be found if their roots can be traced to ancient Hebrew or Egyptian. For instance, there are no last names, and the book avoids starting its names with the letters F, Q, W, and X, which wouldn’t have made sense in a Semitic context.

- Glosses. The text itself provides glosses, or descriptions of meaning, for a small number of its non-English words, such as "Deseret" meaning "honey bee," and "ripliancum" meaning "large, to exceed all." For almost all of these cases, it’s possible to provide plausible meanings that align with the gloss provided by the text.

- Parallelisms. As we’ve discussed previously, the Book of Mormon contains hundreds of literary parallelisms, including chiastic patterns. It turns out that there are some cases where those parallelisms rely on meaningful wordplay, such as the use of the “-iah” suffix in Zedekiah as part of the core of a chiasmus in Helaman 6:7-13.

Apart from this, there’s also evidence to suggest important differences between the names based on the Book of Mormon culture associated with them. Authors generally have a hard time escaping their own naming conventions, even when trying to create names that originate from different cultures and peoples. But Jaredite names in particular show statistically significant differences on a number of linguistic features when compared to Nephite, Mulekite, and Lamanite names. These differences were compared to the dozens of names generated by Tolkien in his Lord of the Rings trilogy, and it was found that the names in the Book of Mormon were more likely to differ on the basis of culture than Tolkien’s were (e.g., Human names differed from Elven names, but otherwise the names weren’t linguistically distinguishable).

The critics, for their part, put forward evidence of their own. They argue that it’s unusual for the Book of Mormon names to not align with a consistent linguistic framework, one that could explain why the names connect with a number of different languages and yet differ from them in ways that can’t be fully accounted for. They also argue that if the Book of Mormon was authentic, and took place in Mesoamerica, we should expect to find names that correspond with the Indigenous peoples and languages of Mesoamerica. That faithful scholars have found only a few, limited possibilities for such connections is evidence, to them, of fabrication.

With that evidence in hand, we now turn to the hypotheses that might be used to explain this evidence, both for and against.

The Hypotheses

The characteristics of the Book of Mormon’s unique names derive from their use by authentic ancient cultures—This theory posits that the Book of Mormon’s unique names are produced the same way names are produced in any other culture—words that carry meaning within a given language and that, over time, experience adaptation and variation in sound change, potentially mixing with and borrowing the features of languages with which they might come in contact. In short, the Book of Mormon’s names should look like they were produced by real people using a living language attached to a living culture. In this case, given that Book of Mormon peoples share a common history with biblical peoples, their names should show a great deal of similarity to biblical names. But they also shouldn’t be exactly the same. They should show variation, creativity, and potentially a bit of borrowing.

This general hypothesis is complicated by the storied language history that the Book of Mormon claims for itself. As we’ve previously discussed, the book describes a mix of peoples each carrying with them potentially different language traditions—Lehi and his tribe would have carried at least Hebrew (probably having a more northern, Aramaic influence), along with Egyptian; the Mulekites may have added a more Phoenician-influenced variety of Semitic to the mix, and the Jaredites, despite some interesting speculation, remain a bit of a question mark, with some potential Sumerian or older Semitic influence, mixed in with a pile of maybes. All this is further complicated by the potential for Jaredite names to have been borrowed, adapted, or transliterated into the Nephites’ already-mixed language prior to their inclusion by Moroni. I think it’s fair to ask whether we would expect the names that came out of that history to fit any sort of consistent framework.

The Book of Mormon’s unique names were invented by Joseph, being inspired by biblical examples. According to this theory, the book’s unique names are yet another example of Joseph’s boundless creativity, and also of how much he was inspired by the text of the King James Bible. Many of the names seem to be pulled straight from its pages, and many of the remainder seem to be very close variations of those biblical names. In that context, it wouldn’t be surprising that many of the names could be traced to Hebrew or other Semitic meanings (though perhaps Egyptian would be a bit unexpected). Whether we would expect those meanings to be actually meaningful within the text itself is another story. This theory would probably have to assume that wordplays, glosses, and fitting parallelisms would be produced by chance—Joseph himself wouldn’t study Hebrew until five years after the publication of the Book of Mormon. We’ll see whether chance is, in this case, up to the task.

Prior Probabilities

PH—Prior Probability of Authentic Names—We’re getting pretty close to the end here, and, based on all the evidence we’ve considered up to this point, the evidence rather decisively favors authenticity, with p = 1—1.44 x 10-33. Here’s where we’ve been so far:

PA—Prior Probability of Fraudulent Names—That would leave our remaining probability for the theory of modern fabrication, at p = 1.44 x 10-33.

Consequent Probabilities

CH—Consequent Probability of Ancient Authorship—Here we can start to consider the negative evidence brought forward by critics, asking how likely we might be to find sets of authentic names that have the following characteristics: 1) a complex linguistic structure that doesn’t seem to easily fit a consistent framework of language change and 2) a lack of Indigenous names from the area where the Book of Mormon is thought to have taken place.

It’s going to be hard to get solid answers here, but we should be able to get conservative estimates in the context of what we know about how languages work in the real world. In terms of our first characteristic, let’s take a look at everyone’s favorite language: English. English is itself a mongrel-like mix of Germanic, Latin, Norwegian and French influence, forming over thousands of years through multiple incursions by conquering invaders and contact with foreigners. Pretend for a minute that you had a small set of around 200 English names, but no access to the rest of the English language, to its literature, or to English peoples themselves. After a bit of study, you could probably find a scattered mix of connections to each of those various source languages. But I’m doubtful that anyone could readily build a coherent and exhaustive framework explaining the pattern of those connections—not without decades upon decades of study by a large army of linguistic researchers. And it absolutely wouldn’t help if those names were then transliterated into yet another language, the way the Book of Mormon’s have likely been. In the end, given the language history implied by the Book of Mormon, I don’t think the lack of a consistent framework all that surprising.

And for the idea that we should find Indigenous names in the Book of Mormon, I see a couple of core issues:

- We don’t have a complete sense of the linguistic environment of ancient Mesoamerica. It’s possible that there are Indigenous names or linguistic features in the Book of Mormon, but that those features or even the languages associated with them have been lost to time.

- Any borrowing from Indigenous cultures has been filtered through the lens of Nephite language and culture. This sort of filtering happens quite frequently, such as through the transliteration or translation of names. It’s common, for instance, for names to have been transliterated into English (“Anglicized”), such as with the name Christopher Columbus (or, rather Cristoforo Colombo).

To have an entire book that transliterates or translates away recognizable traces of language transmission from nearby cultures might be somewhat unusual, but it doesn’t seem impossible.

I don’t have the time or linguistic training required to generate precise likelihood estimates here. But let’s give the critics the benefit of the doubt on both of these items. Let’s say that, with authentic ancient texts, we’d be able to build a consistent linguistic framework a substantial majority of the time (e.g., 90%) on the basis of included names. This would mean that, even for authentic texts, we wouldn’t be able to build that consistent framework about 10% of the time. And let’s assume that there’s only a 1% chance of us not being able to find borrowed names from other local cultures (e.g., Mayan or Aztec names) in the text. I see both of those estimates as exceedingly generous to the critics given the types of issues we discuss above, and they produce a consequent probability of p = .001.

CA—Consequent Probability of Modern Authorship—Now we need to try to figure out how likely we would be, if the book were a fraud, to see Semitic and Egyptian language connections and wordplays. To do that, I had to spend some quality time with the Onomasticon. I started by going through all the non-biblical names in the text—there are technically 188, but many of these are minor variations of the same base word (e.g., Moroni and Moronihah), and some are English translations (e.g., Bountiful and Desolation). After removing those from the list (acknowledging that others might slice things a bit differently), I ended up with a core set of 158 names (see the Appendix for the full table). For each name, I listed the purported ethnicity of origin (i.e., Jaredite; Lehite, which also included Nephite and Mulekite; or Lamanite, which had a small enough sample size that we ignored these in this part of the analysis), the primary source language (e.g., Egyptian, Hebrew, Sumerian, and other Semitic languages; based on the first mention in the Onomasticon, which generally is the best-supported one), the corresponding word in that primary source language, the associated meaning of that word, whether there seemed to be a meaningful wordplay or other fitting connection to the text (e.g., Mulek, the son of a king, having the meaning of “king” or “to reign”; these are detailed in the “Meaning Highlight” column of the table), and whether there was a gloss associated with the word.

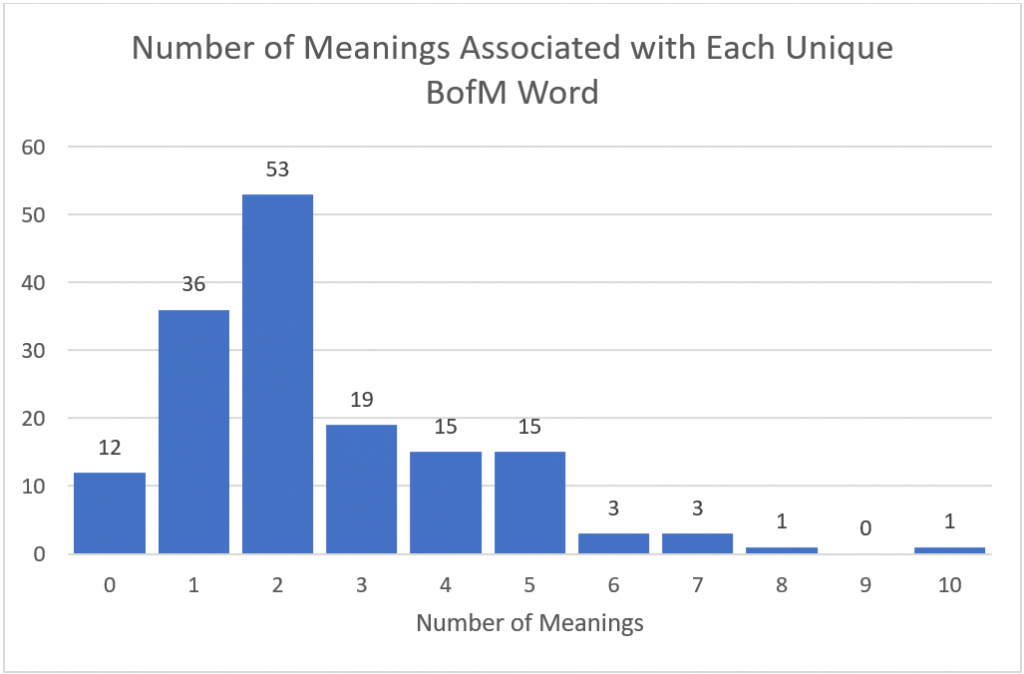

Importantly, I also noted how many potential meanings could be associated with the word based on the Onomasticon (counting meanings that the database listed as “likely” or “less likely,” and not counting those that were “unlikely” or were “remote possibilities”). For example, the word “Lib” is most plausibly connected with a meaning of “rich” in Sumerian, based on the word lib. But it can also be connected with the meanings of “heart” in Akkadian, as well as “dazed silence” and “plunderer,” both of which also occur in Sumerian, for a total of four meanings. This kind of data is extremely relevant for our Bayesian analysis, as it gives us a sense of two things: 1) how easy it is to find chance connections with ancient words, since generally all but one of those meanings has appeared based on chance alone and 2) how many rolls of the dice each word has to create a meaningful wordplay or other meaningful connection. The more meanings we have available, the greater the chance that one of them will happen to form a wordplay out of pure coincidence.

Going through all that data has suggested to me a few key things. First, it doesn’t seem particularly difficult to connect words to one or more ancient languages. Not only do the vast majority of these have a connection, but they usually have many such connections, both within the same language and in multiple languages. Each word had on average 2.47 meanings attached to it. You can get a sense of the distribution of those connections in the figure below.

This perhaps isn’t surprising given the raw number of languages that researchers have delved into in search of these linguistic connections. According to the Onomasticon itself:

When considering possible language sources for the Book of Mormon, Hebrew of the Biblical period is the first choice. Nearly equal in consideration to Hebrew is Egyptian, followed by the other Semitic languages in use at or before the time of Lehi, namely, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Moabite, Ammonite, Akkadian, Aramaic, etc. Semitic languages first attested after the time of Lehi, such as Classical Arabic, the later Aramaic dialects, Ethiopic dialects, etc., are not as relevant as the earlier languages, but may be used with extreme caution. Other non-Semitic languages with which the Hebrews could have had contact before the time of Lehi, such as Hittite, Greek, Hurrian, Sumerian, etc., should be a last resort.

Now it’s important here to not blame the faithful scholars for this particular dilemma. They did exactly what they should do when exploring the potential origins for these words—approach them from as many angles as possible. But it does make it hard to say whether these connections are legitimate or whether they’re based on chance. The best way to tell for sure would be to resurrect Joseph Smith and have him rattle off a couple hundred more names at random. We could then have someone spend a few decades subjecting those additional names to the same linguistic analysis that’s been done in the Onomasticon. Since I have very few spare decades, and even fewer necromantic abilities, we’ll consider that approach to be outside the scope of this analysis. In the meantime, the ratio of words to proposed meanings suggests to me that chance could do a great deal to generate these ancient connections. Though future analyses could show otherwise, I have to assume that it’s not unexpected to have a substantial majority of these words show some sort of connection with ancient languages.

What’s interesting, though, is that there seems to be a discrepancy in the ability to create those connections depending on the culture we’re looking at. If we tabulate the primary language associated with the names for Jaredite and Lehite cultures—including those for which there are no good candidates—the two show very different patterns. The Jaredite names show very few with Egyptian as a best fit (only 1, Deseret, vs. 14 for the Lehite names), and show a higher proportion of names with primary connections other than Egyptian and Hebrew (37% vs. 21%). These differences could be attributed to analytic bias—faithful linguists would be much more likely to accept Sumerian or older Semitic names for Jaredite names than for Lehite ones and might be less likely to look to Egypt as a Jaredite language source. But it’s harder to make that argument for the last and most important difference that we observe in the table—those working on the Onomasticon were far more likely to fail to find workable etymologies for Jaredite names than they were for Lehite ones (28% vs. 6%). If we plug their respective values into a chi-square, we find that this difference is statistically significant, with χ2(1) = 13.5, p = .000232.

| Culture | No Etymology Available | Etymology Available | Primary Language | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | Egyptian | Other | |||

| Jaredite | 12 | 31 | 14 | 1 | 16 |

| Lehite | 7 | 105 | 68 | 14 | 23 |

This is important because those faithful linguists were obviously willing to report etymologies for Jaredite names if they could find them, and probably put just as much effort into researching those as they did for the Lehite ones—in other words, we can’t blame that difference on the analyst. And that difference causes a bit of trouble for our critical hypothesis. It’s perfectly reasonable to assume that Joseph based his names on a biblical template, but, if so, Jaredite names shouldn’t look any different than the Lehite ones. Even if you want to make the extra assumption that he used a different process to create the Jaredite names, that’s still unexpected. The story of the Tower of Babel is just as biblical as any other story in the bible—why not use biblical names in the retelling of that story?

Even if you assume that Joseph did use a separate process to create biblical names, there’s no guarantee that he’d succeed to this degree. This is where we can turn to the study comparing the Book of Mormon’s unique names to the names produced by Tolkien. In crafting culture-specific names, Joseph seems to substantially outstrip his linguistically trained, fiction-writing compatriot. In Wilcox et al.’s statistical analysis, Jaredite names differ significantly from those associated with other cultures, a feat that Tolkien can’t match. Tolkien’s Human names are significantly different from Elven names, but neither of those could be distinguished from Dwarven, Hobbit, or other names.

Now, it’s probably safe to assume that the linguistic features under examination in that study are independent from whether they connect to ancient languages, which means it’s worth thinking about what sort of probability we could attach to that evidence. Unfortunately, the details of that analysis aren’t publicly available, and the study authors no longer have ready access to them, so we can’t see what the F and p values were for the MANOVAs that they ran. All we know is that the set of follow-up comparisons for the Jaredites were all significant at the p = .05 level. Though they could easily have been even smaller, to play it safe we’ll stick with an estimate of p = .05 for this particular piece of evidence.

Before we can complete our estimate, though, we have to go back to our dataset. If the antiquity of the Book of Mormon’s unique names isn’t necessarily surprising, what about the wordplays? How likely would we be to find wordplays like those if the Book of Mormon was fraudulent? To figure that out, I first catalogued all the potential wordplays and other meaningful connections for those names, ending up with a list of 43 names showing those connections. You can see the list and a brief description of each connection in the table below:

Wordplay-like Connections for Unique Book of Mormon Words

| # | Word | Primary Language | Word | Meaning | Meaning Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Abinadom | Hebrew | abinadam | my father is a wanderer | His fathers (several generations back) were definitely wanderers. |

| 3 | Abish | Hebrew | abiis | my father is a man | Interesting wordplay here in Alma 19:16. |

| 8 | Alma | Hebrew | elema | lad of God | Referred to initially as a young man. |

| 10 | Amalickiah | Hebrew | amalekiah | Yahweh is king | Ironic, since he wanted himself to become king, rather than God. |

| 11 | Amaron | Ammonite | amaron | to speak, say, or command | This and the similar “Ammaron” were names given to scribes/historians in different eras, and the name could be fitting. |

| 15 | Ammaron | Semitic | ammaron | wordsmith/speaker | Nephite scribe and historian |

| 22 | Ani-Anti | Egyptian | ‘n.tj | he of Ani | Anti as an Egyptian “he of” makes substantial sense in the context of place names such as “Anti-Nephi-Lehi” |

| 24 | Antion | Egyptian | int-on | buying, bringing | Makes sense in the context of a measure of monetary weight. Also allows Antionah and Antionum to make sense as “gold-man” and “gold-city” respectively. |

| 27 | Archeantus | Greek | apxwv | chief civil magistrate | Could be a fitting name for a military leader. |

| 31 | Comnor | Akkadian | karmu | ruin, ruin heap | This was the site of a large battle with tremendous loss of life. |

| 37 | Cumorah | Akkadian | kamaru | to heap up, layer up | An appropriate name for a hill. |

| 39 | Deseret | Egyptian | dsrt | desert; also a ritual designation for “bee” | A potential fit for the gloss of “honey bee” applied in the text. |

| 43 | Ezrom | Hebrew | hsrom | enclosed, bound together | Could be an appropriate name for a weight-based measure (e.g., weighing bags). |

| 44 | Gadianton | Hebrew | gadi-anton | my fortune is oppression | A fitting name for a robber band–also “gadd” in Hebrew means “band/bandits” which would also be fitting. |

| 46 | Gazelem | Hebrew | gazarim | halves; cut in two; polishing | A good name for a set of polished stones. |

| 52 | Gimgimno | Egyptian | gmgmno | broken city | This was a city which sank into the earth. |

| 53 | Hagoth | Hebrew | hagot | curious; skillful; devisings | Hagoth is said to be an exceedingly curious (skillful) man. |

| 55 | Helaman | Hebrew | hlm-an | seer; visionary | A solid prophetic name. |

| 58 | Hermounts | Egyptian | hr-mntw | sanctuary of the god of wild places and things | This is a wilderness area infested by wild and ravenous beasts. |

| 59 | Heshlon | Hebrew | sl-on | place of exhaustion/crushing | This is the place where Shared defeated Coriantumr in battle. |

| 61 | Irreantum | Semitic | irwyantmm | abundant watering of completeness | Aligns with the gloss of a place of many waters. |

| 65 | Jershon | Hebrew | yerson | place of inheritance | This was a land given as an inheritance. |

| 83 | Limnah | Hebrew | nimna | counted, reckoned | Similar to the root words for weight measures, which is its use in the Book of Mormon |

| 90 | Minon | Hebrew | mnn | to be bounteous | Land on a river where flocks were raised. |

| 92 | Moriancumer | Akkadian | mu-iru-kumru | leader-priest | An appropriate title for the Jaredite nation’s founding religious figure. |

| 94 | Mormon | Egyptian | mrmn | love is established | A number of examples of wordplay tying the word “Mormon” to “love.” This word is also found in Egyptian in symbols taken from the plates, and that were ascribed by Frederick G. Williams as meaning “The Book of Mormon. The demotic symbol for “book” is also found in those symbols. Also worth mentioning is the potential Hebrew meaning of Mormon which would be mrm-on, or “desirable place,” which would be fitting given the context of the Book of Mormon place names such as “the Waters of Mormon.” |

| 97 | Mulek | Hebrew | mlk | to reign; king | A fitting name for the son of a king, and features a rather dramatic correspondence to the attested malchiah, the son of the king. |

| 98 | Nahom | Hebrew | nhm | to groan (of persons) | A good name for a burial ground and place of mourning. |

| 101 | Nephi | Egyptian | nfr | good, beautiful | Substantial wordplay with the word “good” in Nephi 1 and elsewhere. |

| 107 | Onidah | Hebrew | on-dah | he attends to my strength | A fitting name for a place of arms. |

| 115 | Rabbanah | Hebrew | rbb-an | Large, great, many | Matches the gloss quite well. |

| 116 | Rameumptom | Hebrew | rama-omed-om | stand at a high place | A rather spot-on name for a high place of standing. |

| 118 | Ripliancum | Sumerian | rib-lian | strong waters | Large waters, to exceed all. |

| 121 | Sebus | Semitic | sbs | place of gathering | A fitting name for a gathering place for flocks. |

| 123 | Senine | Egyptian | snny | a unit of silver currency | A weight-based unit of currency. |

| 125 | Seon | Hebrew | se’a | hebrew volumetric measure | A weight-based unit of currency. |

| 127 | Shazer | Egyptian | shazher | pass of the trees | A useful area in which to make a new wooden bow. |

| 133 | Sheum | Sumerian | se’um | barley, grain cereal | This is a food item implied to be a grain. |

| 147 | Zarahemla | Hebrew | zer-a-hemla | seed of compassion | A few interesting wordplays in Alma 27:4-5 and Alma 53:10-13. |

| 148 | Zeezrom | Hebrew | ze-ezrom | he of silver | A good name for someone offering a bribe of silver to Alma and Amulek. |

| 156 | Zerin | Qatabanian | z.rm | to be sharp | An appropriate name for a mountain. |

| 157 | Ziff | Akkadian | ziv | appearance, luster, glow | A fitting name for a potentially shiny metal. |

| 158 | Zoram | Hebrew | zo-ram | the one who is high | Wordplay in referring to the Zoramites as “high” or “lifted up” in Alma 38:3-5. |

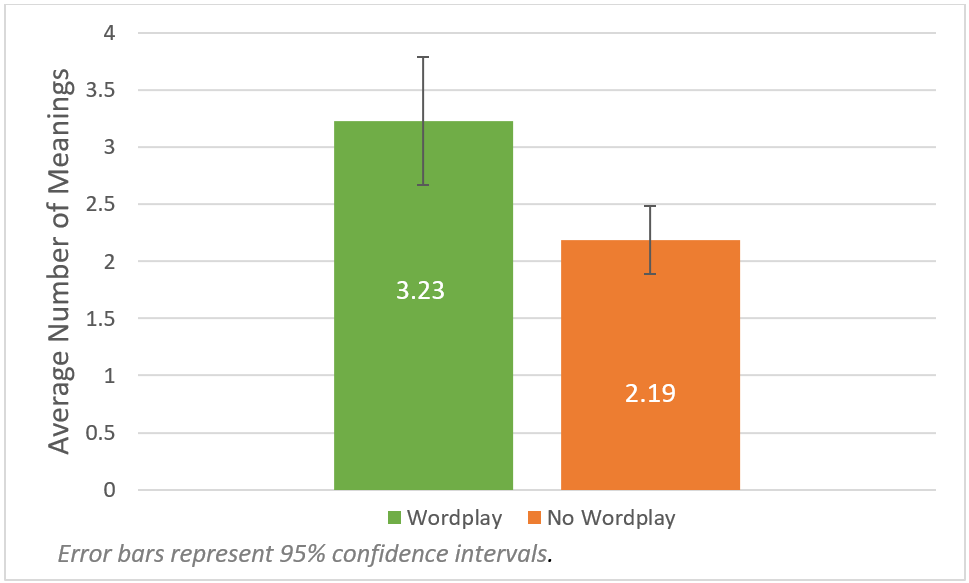

When I put together this list, it definitely looked pretty impressive from my point of view. Over a quarter of the book’s unique names seemed to allow for some variety of wordplay, and it seemed unlikely that you could get something close to that number just through spurious connections in other languages. I wanted to check one thing out first, though. If some of our wordplays are due to chance, we’d expect words implicated in wordplays to have more meanings associated with them than words not implicated in wordplay—the more meanings attached to the word, the more likely it would be to have a wordplay associated with it by chance, and thus is more likely to end up on the Book of Mormon’s list of purported wordplays. Indeed, if we compare the average number of meanings for wordplay words to those for non-wordplay words, we end up with a significant difference, with a two-tailed t(156) = 3.42, p = .0008, as shown in the figure below:

So that already gives us a sense that chance might be playing a role. These names also raise the interesting question of when some of these scriptural figures got their names. Did Amaron, Hagoth, and Zeezrom get their names as children, and then just happen to go on to live their lives in a way that was ironically consistent with those names? Or did some later scribe or editor apply fitting names to those people to incorporate them better into the narrative? We don’t have time to delve into that question more deeply, but it’s possible that chance is a decent explanation for these coincidences.

To get an even better sense of what chance might be doing here, what I needed to do was find a way to generate random word meanings for each of the Book of Mormon’s unique words and see how well those meanings fit in the context of the Book of Mormon, searching for potential wordplays.

To do that, I went through the Collins Spanish-English Dictionary, noting the word that seemed the closest sound match for each unique Book of Mormon word. If you’re curious, you can take a look at the words I picked in a separate table in the Appendix. I stress that these words don’t—or at least shouldn’t—have anything to do with the Book of Mormon, and I’m not proposing that the Book of Mormon’s unique names were drawn from a Spanish dictionary. All this exercise represented was a relatively objective process for assigning random meanings to the Book of Mormon’s unique names, one that provided decent protections against cherry-picking.

In the end, when taking a look at those names, I was surprised at how many of those random meanings seemed to show a decent fit for the context of those words. Some of them even afforded for interesting wordplay, such as Alma, which means “soul” in Spanish, repeatedly using the word “soul” in Alma 36. There were 10 in all, which you can find in the table below.

| # | Word | Spanish Word | Spanish Meaning | Meaning Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Agosh | agostar | to burn up or wither | A potentially appropriate place for a battle location. |

| 8 | Alma | alma | soul | Could be potentially meaningful given Alma’s frequent use of the word “soul” in Alma 36. |

| 14 | Amlici | amolarse | to take offense | Potentially appropriate name for a rebel; potential wordplay with nearby “contentions.” |

| 34 | Corom | corona | crown, halo, wreath | A fitting name for a king. |

| 37 | Cumorah | cumulo | heap, accumulation | An alright name for a hill. |

| 53 | Hagoth | hago | I made; I built | Hagoth certainly built things. |

| 98 | Nahom | nahual | spirit | Not an unfitting meaning for a burial ground. |

| 139 | Shule | sultan | sultan | Potentially an appropriate appelation for a king. |

| 140 | Shum | sumar | to add up | Potentially meaningful as a weight measure. |

| 147 | Zarahemla | zaramullo | affected, conceited, finicky, amusing | Conceited could potentially work, as Zarahemla is sometimes associated with pride, though its a minor connection to a minor meaning of the word. |

It’s entirely possible that these wouldn’t pass muster with the Paul Hoskissons or Matt Bowens of the world, but they certainly seem to be the same sort of connections that scholars would find interesting if they happened upon them in Hebrew or Egyptian.

Now, 10 seems like it’s substantially less than 43, but 10 is actually somewhat bad news. Remember we don’t just get one roll of the dice when we’re looking for these wordplays. Recall that each word had an average of 2.47 meanings associated with it. That means we get 2.47 rolls of the dice, each likely to produce around 10 wordplays or wordplay-like connections out of our set of 158, purely on the basis of chance. The probability that a single roll of that meaning-die not producing a wordplay would be 148/158, or .9367. The probability that a word would go through 2.47 rolls of that same die without producing a wordplay would be .93672.47, or about .85. By subtracting that from 1, we have the probability that a given unique Book of Mormon name would be able to form a wordplay after being compared with 2.47 randomly generated meanings: .15, which in our set of 158 would produce about 24 wordplay-like connections, all of them spurious.

Now 24 and 43 are different, but not astronomically so. Plugging those values into a chi-square alongside the ones from the Onomasticon dataset, and we get χ2(1) = 6.84, p = .008. In other words, though it’s significantly different from the 24 we would expect to find with a randomly generated set of meanings, it’s not particularly improbable, at least not in the context of other evidence we’ve considered. Regardless, with that value in hand we have all we need to build our overall probability estimate.

But wait! What about the other types of evidence listed in the Book of Mormon Central video: glosses, consistency, and parallelism? Well, for glosses, it seems to me to be an extension of the antiquity issue—given how readily words can be tied to ancient languages, and given that faithful scholars would be especially motivated to pull out all the linguistic stops in search of support for a gloss, that such support can be found may not be unexpected. That, combined with the relatively small sample size for those glosses (4, by my count), is going to make it hard to incorporate into our analysis.

In terms of consistency, assuming that Joseph was especially attuned to the biblical pattern, we’d expect those names to show some consistency. Such attunement wouldn’t necessarily prevent him from messing that up on occasion, though, and if Joseph was as creative as people sometimes believe him to be, nothing would’ve stopped him from throwing in a name or two starting with F or Q. But given that it broadly fits the hypothesis, it’s going to be hard to give it much weight in our analysis. As one of several ways that we’re exercising a fortiori reasoning here, we’ll just set that evidence aside.

And, for the example of parallelism, we’d likely treat that as an example of a wordplay-like connection, but the only example of which I’m aware is with the name Zedekiah—a biblical name rather than a name unique to the Book of Mormon. We’ll be setting aside that issue as well.

All told, then, we have three independent pieces of positive evidence to account for: 1) Jaredite names being less likely to show a connection with Semitic, Sumerian, or Egyptian languages, relative to Lehite names (p = .00232); 2) Jaredite names significantly differing from those of other cultures on a number of other linguistic characteristics (p = .05); and 3) Book of Mormon names showing somewhat more wordplay or wordplay-like connections than we’d expect on the basis of chance (p = .008). Multiplying all those together, we get p = 9.28 x 10-8. That’s what we’ll use for our consequent probability.

Posterior Probability

PH = Prior Probability of the Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the likelihood of authentic Book of Mormon names, or p = 1 — 1.44 x 10-33)

CH = Consequent Probability of the Hypothesis (the estimated likelihood of observing the evidence if the names were authentic, or p = .001)

PA = Prior Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (our initial estimate of the likelihood of the names being fraudulent, or p = 1.44 x 10-33)

CA = Consequent Probability of the Alternate Hypothesis (the estimated likelihood of observing wordplays and cultural distinctions if the names are fraudulent, or p = 9.28 x 10-8)

PostProb = Posterior Probability (the updated likelihood of an authentic Book of Mormon)

| PH = 1 — 1.44 x 10-33 | |

| PostProb = | PH * CH |

| (PH * CH) + (PA * CA) | |

| PostProb = | (1 — 1.44 x 10-33 * .001) |

| ((1 — 1.44 x 10-33) * .001) + (1.44 x 10-33 * 9.28 x 10-8) | |

PostProb = 1 — 1.34 x 10-37

Lmag = Likelihood Magnitude (an estimate of the number of orders of magnitude that the probability will shift, due to the evidence)

Lmag = log10(CH / CA)

Lmag = log10(.001 / 9.28 x 10-8)

Lmag = log10(10776)

Lmag = 4

Conclusion

All told, in the Onomasticon we seem to have evidence that’s somewhat informative, though perhaps not as informative as it might’ve seemed at first glance. Some aspects of the book’s unique names appear unexpected, particularly differences between Jaredite and Lehite names, and the number of wordplay-like connections that those words form with ancient languages. However, what our results also suggest is that some, and perhaps many, of those connections could have been produced by chance. It’s not likely that all 43 that we identify here are spurious, but some of them likely are. That doesn’t make the study of wordplays any less interesting or worthwhile. Assuming that the book is authentic, such wordplays can absolutely help to deepen our understanding of the text and give new appreciation for that literary talents of its ancient authors. But it should lead us to demonstrate a bit of caution when it comes to interpreting each of the potential examples. And, when taking into account the Onomasticon’s unresolved issues, it means that it doesn’t represent overwhelming evidence in the Book of Mormon’s favor.

Skeptic’s Corner

If a critic really wanted to convince me that the Onomasticon was a liability for an authentic Book of Mormon, there are a few places they could do it. First, they’d need to demonstrate to me how easy it should be for us to build a consistent linguistic framework on the basis of 200 names, given the complex linguistic history described in the book—so easy that we’d expect to not be able to less than 10% of the time. I don’t see how it could be easy, but maybe it is and I’m just too ignorant to grasp it. Second, they could show me how rare it would be for local names from other cultures to be transliterated or translated away in ancient texts. Maybe it’s even less rare than the 1% I’ve assigned it. If critics want to frame this as a silver bullet, they’re going to have to demonstrate a strong statistical basis for one or both of these points.

It wouldn’t hurt to work to weaken the positive side of the argument either. Maybe my identification of 10 Spanish wordplays is unexpectedly low, and that if I repeated that process 10 or 100 times the average number of spurious wordplays would be much higher. Maybe Joseph’s success in differentiating Jaredite names would also make it less likely for us to identify ties with ancient languages, creating a dependence between those two pieces of evidence. Maybe analytic bias (including my own) can account for everything we see here, in ways I can’t yet fathom. Until that evidence is presented to me clearly, though, I’ll claim the Onomasticon as a minor asset pointing us toward authenticity.

Next Time, in Episode 22:

And with that, our review of the book’s positive evidence is complete. Next time, the critics will get one last shot as we take a look at the evidence associated with the Book of Abraham.

Questions, ideas, and insulting nicknames can have their etymology traced through BayesianBoM@gmail.com or submitted as comments below.

Appendix

Onomasticon Table

| # | Word | BofM Ethnicity | # of Meanings | Primary Language | Word | Meaning | Meaning Highlight | Book of Mormon Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abinadi | Lehite | 5 | Akkadian | abanada | my father is cast down | ||

| 2 | Abinadom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | abinadam | my father is a wanderer | His fathers (several generations back) were definitely wanderers. | |

| 3 | Abish | Lamanite | 3 | Hebrew | abiis | my father is a man | Interesting wordplay here in Alma 19:16. | |

| 4 | Ablom | Jaredite | 2 | Ugaritic | blm | green meadows | ||

| 5 | Agosh | Jaredite | 7 | Sumerian | agush | toil, labour | ||

| 6 | Aha | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | h’ | god is a brother | ||

| 7 | Akish | Jaredite | 2 | Hebrew | ikkesh | twist, pervert | ||

| 8 | Alma | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | elema | lad of God | Referred to initially as a young man. | |

| 9 | Amaleki | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | amaliki | the Amalekite | ||

| 10 | Amalickiah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | amalekiah | Yahweh is king | Ironic, since he wanted himself to become king, rather than God. | |

| 11 | Amaron | Lehite | 3 | Ammonite | amaron | to speak, say, or command | This and the similar "Ammaron" were names given to scribes/historians in different eras, and the name could be fitting. | |

| 12 | Amgid | Jaredite | 2 | Semitic | amgid | people of fortune | ||

| 13 | Aminadi | Lehite | 3 | Akkadian | amanada | my people is praised | ||

| 14 | Amlici | Lehite | 4 | Semitic | mlyk | I have made a king over you | ||

| 15 | Ammaron | Lehite | 2 | Semitic | ammaron | wordsmith/ speaker | Nephite scribe and historian | |

| 16 | Amnigaddah | Jaredite | 1 | Semitic | mngd | my maker is fate | ||

| 17 | Amnihu | Lehite | 1 | Semitic | mnhu | crafter of faith | ||

| 18 | Amnor | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | mmnwr | people of light | ||

| 19 | Amulek | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | a-mulek | the Mulek | ||

| 20 | Amulon | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | amal-on | trouble, toil, labour | ||

| 21 | Angola | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | ‘aynglh | revealed spring | ||

| 22 | Ani-Anti | Lamanite | 5 | Egyptian | ‘n.tj | he of Ani | Anti as an egyptian "he of" makes substantial sense in the context of place names such as "Anti-Nephi-Lehi" | |

| 23 | Antiomno | Lamanite | 2 | Egyptian | ntymn | he of faithfulness | ||

| 24 | Antion | Lehite | 5 | Egyptian | int-on | buying, bringing | Makes sense in the context of a measure of monetary weight. Also allows Antionah and Antionum to make sense as "gold-man" and "gold-city" respectively. | |

| 25 | Antiparah | Lehite | 5 | Egyptian | nty-pr’h | he of the great house | ||

| 26 | Antum | Lehite | 2 | Egyptian | n.tm(w) | many waters | ||

| 27 | Archeantus | Lehite | 2 | Greek | apxwv | chief civil magistrate | Could be a fitting name for a military leader. | |

| 28 | Cezoram | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | zezoram | he of Zoram | ||

| 29 | Cohor | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 30 | Com | Jaredite | 2 | Sumerian | gum | to crush | ||

| 31 | Comnor | Jaredite | 4 | Akkadian | karmu | ruin, ruin heap | This was the site of a large battle with tremendous loss of life. | |

| 32 | Corianton | Lehite | 2 | Akkadian | garium | opponent, enemy | ||

| 33 | Corihor | Jaredite | 2 | Akkadian | hurianum | plant | ||

| 34 | Corom | Jaredite | 1 | Sumerian | kurum | judge; decide | ||

| 35 | Cumeni | Jaredite | 5 | Hebrew | kmn | hidden away | ||

| 36 | Comums | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | qum | rise up, stand up | ||

| 37 | Cumorah | Lehite | 4 | Akkadian | kamaru | to heap up, layer up | An appropriate name for a hill. | |

| 38 | Cureloms | Jaredite | 2 | Hebrew | garal | to roll forth | ||

| 39 | Deseret | Jaredite | 3 | Egyptian | dsrt | desert | A name for upper Egypt, which was symbolized by the bee. | honey-bee |

| 40 | Emer | Jaredite | 6 | Ugaritic | mr | to speak; to command | ||

| 41 | Emron | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | amar | to speak | ||

| 42 | Ethem | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 43 | Ezrom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | hsrom | enclosed, bound together | Could be an appropriate name for a weight-based measure (e.g., weighing bags). | |

| 44 | Gadianton | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | gadi-anton | my fortune is oppression | A fitting name for a robber band–also "gadd" in Hebrew means "band/bandits" which would also be fitting. | |

| 45 | Gadiomnah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | gad-mn | faithful to fortune | ||

| 46 | Gazelem | Lehite | 10 | Hebrew | gazarim | halves; cut in two; polishing | A good name for a set of polished stones. | |

| 47 | Gid | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | gid | sinew | ||

| 48 | Giddonah | Lehite | 3 | — | — | — | ||

| 49 | Giddianhi | Lehite | 2 | — | — | — | ||

| 50 | Gidgiddoni | Lehite | 2 | — | — | — | ||

| 51 | Gilgah | Jaredite | 1 | — | — | — | ||

| 52 | Gimgimno | Lehite | 5 | Egyptian | gmgmno | broken city | This was a city which sank into the earth. | |

| 53 | Hagoth | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | hagot | curious; skillful; devisings | Hagoth is said to be an exceedingly curious (skillful) man. | |

| 54 | Hearthom | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | hartom | soothsayer-priests | ||

| 55 | Helaman | Lehite | 5 | Hebrew | hlm-an | seer; visionary | A solid prophetic name. | |

| 56 | Helorum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | helyarom | may the hero exalt | ||

| 57 | Hem | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | ham | father-in-law | ||

| 58 | Hermounts | Lehite | 2 | Egyptian | hr-mntw | sanctuary of the god of wild places and things | This is a wilderness area infested by wild and ravenous beasts. | |

| 59 | Heshlon | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | sl-on | place of exhaustion/ crushing | This is the place where Shared defeated Coriantumr in battle. | |

| 60 | Himni | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | hmn | — | ||

| 61 | Irreantum | Lehite | 5 | Semitic | irwyantmm | abundant watering of completeness | Aligns with a meaning of a place of many waters. | many waters |

| 62 | Jacom | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | yaqom | let the Lord rise up | ||

| 63 | Jarom | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | joram | Jehovah is exalted | ||

| 64 | Jashon | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | ja-s’n | Jehovah gives rest | ||

| 65 | Jershon | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | yerson | place of inheritance | This was a land given as an inheritance. | |

| 66 | Joneum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | jo-neum | Jehovah is the oracle | ||

| 67 | Josh | Lehite | 5 | Hebrew | josiah | Jehovah has healed | ||

| 68 | Kib | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 69 | Kim | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 70 | Kimnor | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 71 | Kishkumen | Jaredite | 2 | Sumerian | kish-kumen | extension of biblical place-name | ||

| 72 | Kumen | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | kmn | to hide up | ||

| 73 | Lachoneus | Lehite | 1 | Greek | lachoneus | Laconian | ||

| 74 | Lamah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | lmh | why? | ||

| 75 | Laman | Lehite | 3 | Safaitic | l’mn | mender | ||

| 76 | Lamoni | Lehite | 2 | — | — | — | ||

| 77 | Lehi | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | lhy | jaw, cheek bone | ||

| 78 | Lehonti | Lehite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 79 | Liahona | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | l-yah-annu | to God is light | compass (crafty contrivance; circle or globe) | |

| 80 | Lib | Jaredite | 5 | Sumerian | lib | to be rich, well-off | ||

| 81 | Limher | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | mhr | hasten | ||

| 82 | Limhi | Lehite | 3 | Ugaritic | limhay | the people live | ||

| 83 | Limnah | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | nimna | counted, reckoned | Similar to the root words for weight measures, which is its use in the Book of Mormon | |

| 84 | Luram | Lehite | 3 | Aramaic | lu-rum | may he be exalted | ||

| 85 | Mahah | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 86 | Manti | Lehite | 1 | Egyptian | mntw | Month (god) | ||

| 87 | Mathoni | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | mantan | my gift | ||

| 88 | Melek | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | melek | king | ||

| 89 | Middoni | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | mdd-on | place of measurement | ||

| 90 | Minon | Lehite | 6 | Hebrew | mnn | to be bounteous | Land on a river where flocks were raised. | |

| 91 | Mocum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | maqom | place, station | ||

| 92 | Moriancumer | Jaredite | 2 | Akkadian | mu-iru-kumru | leader-priest | An appropriate title for the Jaredite nation’s founding religious figure. | |

| 93 | Morianton | Jaredite | 2 | — | — | — | ||

| 94 | Mormon | Lehite | 4 | Egyptian | mrmn | love is established | A number of examples of wordplay tying the word "Mormon" to "love." This word is also found in Egyptian in symbols taken from the plates, and that were ascribed by Frederick G. Williams as meaning "The Book of Mormon. The demotic symbol for "book" is also found in those symbols. Also worth mentioning is the potential Hebrew meaning of Mormon which would be mrm-on, or "desirable place," which would be fitting given the context of the Book of Mormon place names such as "the Waters of Mormon." | |

| 95 | Moroni | Lehite | 3 | Egyptian | mrny | my beloved | ||

| 96 | Mosiah | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | mosi-yahu | the Lord delivers/saves | ||

| 97 | Mulek | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | mlk | to reign; king | A fitting name for the son of a king, and features a rather dramatic correspondence to the attested malchiah, the son of the king | |

| 98 | Nahom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | nhm | to groan (of persons) | A good name for a burial ground and place of mourning. | |

| 99 | Neas | Lehite | 3 | Mixe | nij | chili-pepper | ||

| 100 | Nehor | Jaredite | 2 | Hebrew | nahor | — | ||

| 101 | Nephi | Lehite | 6 | Egyptian | nfr | good, beautiful | Substantial wordplay with the word "good" in Nephi 1 and elsewhere. | |

| 102 | Neum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | neum | visionary utterance | ||

| 103 | Ogath | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 104 | Omer | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | mr | commander | ||

| 105 | Omner | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | amner | divine kinsman is light | ||

| 106 | Omni | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | mn | to be true or faithful | ||

| 107 | Onidah | Lehite | 5 | Hebrew | on-dah | he attends to my strength | A fitting name for a place of arms. | |

| 108 | Onti | Lehite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 109 | Orihah | Jaredite | 1 | Hebrew | uriyahu | my light is Jehova | ||

| 110 | Paanchi | Lehite | 1 | Egyptian | p3-‘nh | the living one | ||

| 111 | Pachus | Lehite | 2 | Egyptian | p3-hsy | he is praised | ||

| 112 | Pacumeni | Lehite | 2 | Egyptian | pkmt | the Egyptian | ||

| 113 | Pagag | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 114 | Pahoran | Lehite | 5 | Canaanite | pah.ura | the Syrian | ||

| 115 | Rabbanah | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | rbb-an | Large, great, many | Matches the gloss quite well. | Powerful or great king |

| 116 | Rameumptom | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | rama-omed-om | stand at a high place | A rather spot-on name for a high place of standing. | |

| 117 | Riplah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | riblah | fertility | ||

| 118 | Ripliancum | Jaredite | 2 | Sumerian | rib-lian | strong waters | Large waters, to exceed all. | |

| 119 | Sariah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | sryah | the princess of Jehovah | ||

| 120 | Seantum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | s’ntmm | perfection in full measure | ||

| 121 | Sebus | Lehite | 2 | Semitic | sbs | place of gathering | A fitting name for a gathering place for flocks. | |

| 122 | Seezoram | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | zezoram | he of Zoram | ||

| 123 | Senine | Lehite | 3 | Egyptian | snny | a unit of silver currency | A weight-based unit of currency. | |

| 124 | Senum | Lehite | 1 | Arabic | snm | to ascend | ||

| 125 | Seon | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | se’a | hebrew volumetric measure | A weight-based unit of currency. | |

| 126 | Shared | Jaredite | 2 | Ugaritic | srd | to present an offering from God | ||

| 127 | Shazer | Lehite | 5 | Egyptian | shazher | pass of the trees | A useful area in which to make a new wooden bow. | |

| 128 | Shelem | Jaredite | 5 | Hebrew | slm | peace offering | ||

| 129 | Shemlon | Lehite | 7 | Hebrew | simla-on | covered place | ||

| 130 | Shemnon | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | smn | place of fatness | ||

| 131 | Sherem | Lehite | 2 | Assyrian | saramu | to cut out | ||

| 132 | Sherrizah | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | srs | to swarm, teem | ||

| 133 | Sheum | Lehite | 4 | Sumerian | se’um | barley, grain cereal | This is a food item implied to be a grain. | |

| 134 | Shez | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 135 | Shiblon | Jaredite | 4 | Hebrew | sbl | flowing skirt | ||

| 136 | Shim | Jaredite | 3 | Hebrew | sem | name, fame, renown | ||

| 137 | Shimnilom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | smn-ilom | name/monument of wealth | ||

| 138 | Shiz | Jaredite | 0 | — | — | — | ||

| 139 | Shule | Jaredite | 2 | Sumerian | su’la | belief, trust | ||

| 140 | Shum | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | sum | garlic | ||

| 141 | Shurr | Jaredite | 8 | Hebrew | srr | foe, enemy | ||

| 142 | Sidom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | swd | to catch, hunt | ||

| 143 | Siron | Lehite | 1 | Phoenician | siryon | armor | ||

| 144 | Teancum | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | de-ancum | the one from ancum | ||

| 145 | Teomner | Lehite | 1 | Hebrew | de-omner | the one from omner | ||

| 146 | Tubaloth | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | tubal-oth | gift, presentation | ||

| 147 | Zarahemla | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | zer’a-hemla | seed of compassion | A few interesting wordplays in Alma 27:4-5 and Alma 53:10-13. | |

| 148 | Zeezrom | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | ze-ezrom | he of silver | A good name for someone offering a bribe to Alma and Amulek. | |

| 149 | Zemnarihah | Lehite | 1 | Egyptian | zmn-h3-r’ | — | ||

| 150 | Zenephi | Lehite | 3 | Hebrew | Ze-nfy | he of Nephi | ||

| 151 | Zeniff | Lehite | 2 | Hebrew | zainab | — | ||

| 152 | Zenock | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | znq | to leap | ||

| 153 | Zenos | Lehite | 3 | Greek | ze-nos | guest, host, stranger | ||

| 154 | Zerahemnah | Lehite | 4 | Hebrew | zera’-ham-ma-na-h | seed of appointment/ measurement | ||

| 155 | Zeram | Lehite | 7 | Hebrew | zerem | thunder | ||

| 156 | Zerin | Jaredite | 1 | Qatabanian | z.rm | to be sharp | An appropriate name for a mountain. | |

| 157 | Ziff | Lehite | 2 | Akkadian | ziv | appearance, luster, glow | A fitting name for a potentially shiny metal. | |

| 158 | Zoram | Lehite | 5 | Hebrew | sur-am | the rock is the kinsman | Wordplay in referring to the Zoramites as "high" or "lifted up" in Alma 38:3-5. |

Spanish Meaning Generation

| # | Word | Spanish Word | Spanish Meaning | Meaning Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abinadi | abintestato | intestate (dying before having made a will) | No |

| 2 | Abinadom | abintestato | intestate (dying before having made a will) | No |

| 3 | Abish | abisal | deep sea | No |

| 4 | Ablom | ablandador | a thing that softens | No |

| 5 | Agosh | agostar | to burn up or wither | A potentially appropriate place for a battle location. |

| 6 | Aha | ahi | there | No |

| 7 | Akish | achechadera | hiding place | No |

| 8 | Alma | alma | soul | Could be potentially meaningful given Alma’s frequent use of the word "soul" in Alma 36. |

| 9 | Amaleki | amalgama | to combine, blend | No |

| 10 | Amalickiah | amalia | work | No |

| 11 | Amaron | amarar | to land, splash, or touch down | No |

| 12 | Amgid | amigdala | tonsil | No |

| 13 | Aminadi | aminorar | to cut, reduce | No |

| 14 | Amlici | amolarse | to take offense | Potentially appropriate name for a rebel; potential wordplay with nearby "contentions." |

| 15 | Ammaron | amarar | to land, splash, or touch down | No |

| 16 | Amnigaddah | amniotico | pertaining to the little lamb | No |

| 17 | Amnihu | amniotico | pertaining to the little lamb | No |

| 18 | Amnor | amor | love | No |

| 19 | Amulek | amuleto | amulet, charm | No |

| 20 | Amulon | amuleto | amulet, charm | No |

| 21 | Angola | angostar | to narrow, make smaller | No |

| 22 | Ani-Anti | anil | indigo, blue | No |

| 23 | Antiomno | antimonio | metallic element | No |

| 24 | Antion | antinomia | conflict of authority | No |

| 25 | Antiparah | antipara | screen | No |

| 26 | Antum | antuca | parasol | No |

| 27 | Archeantus | archangel | archangel | No |

| 28 | Cezoram | cerezo | cherry tree | No |

| 29 | Cohor | cororte | cohort | No |

| 30 | Com | como | how | No |

| 31 | Comnor | comodo | comfortable, handy, lazy | No |

| 32 | Corianton | corriente | common, usual, ordinary | No |

| 33 | Corihor | corajina | fit of rage | No |

| 34 | Corom | corona | crown, halo, wreath | A fitting name for a king. |

| 35 | Cumeni | cume | baby of the family | No |

| 36 | Comums | comuna | commune, municipality | No |

| 37 | Cumorah | cumulo | heap, accummulation | An alright name for a hill. |

| 38 | Cureloms | curena | gun carriage | No |

| 39 | Deseret | desertar | to abandon | No |

| 40 | Emer | emerito | emeritus | No |

| 41 | Emron | emirato | emirate | No |

| 42 | Ethem | ethos | ethos | No |

| 43 | Ezrom | estarse | to stay | No |

| 44 | Gadianton | gaditano | from Cadiz | No |

| 45 | Gadiomnah | gachon | charming, sweet, sexy | No |

| 46 | Gazelem | gacela | gazelle | No |

| 47 | Gid | giba | hump, hunchback, nuisance | No |

| 48 | Giddonah | gibon | gibbon | No |

| 49 | Giddianhi | gibon | gibbon | No |

| 50 | Gidgiddoni | gibado | with a hump | No |

| 51 | Gilgah | gilar | to watch, keep tabs on | No |

| 52 | Gimgimno | gimnasio | gym | No |

| 53 | Hagoth | hago | I made; I built | Hagoth certainly built things. |

| 54 | Hearthom | harton | large banana; gluttonous | No |

| 55 | Helaman | helenico | Hellenic; Greek | No |

| 56 | Helorum | heliotropo | Heliotrope (flower) | No |

| 57 | Hem | hembra | female, nut, eye | No |

| 58 | Hermounts | hermoso | beautiful, lovely, nice and big | No |

| 59 | Heshlon | hexagono | hexagon | No |

| 60 | Himni | himno | hymn | No |

| 61 | Irreantum | irrealista | unrealistic | No |

| 62 | Jacom | jaco | small horse, nag | No |

| 63 | Jarom | jarron | vase | No |

| 64 | Jashon | jaspe | jasper | No |

| 65 | Jershon | jerezano | from Jerez | No |

| 66 | Joneum | jonico | ionic | No |

| 67 | Josh | Josue | Joshua | No |

| 68 | Kib | kiki | joint, reefer | No |

| 69 | Kim | kimona | kimono | No |

| 70 | Kimnor | kimona | kimono | No |

| 71 | Kishkumen | kuchen | fancy cake | No |

| 72 | Kumen | kuchen | fancy cake | No |

| 73 | Lachoneus | laconismo | laconic manner; terse | No |

| 74 | Lamah | lama | mud, slime, ooze | No |

| 75 | Laman | lama | mud, slime, ooze | No |

| 76 | Lamoni | laminar | to laminate; to roll | No |

| 77 | Lehi | legia | legionnarie | No |

| 78 | Lehonti | lehendakari | government head | No |

| 79 | Liahona | liana | to climb like a vine | No |

| 80 | Lib | libro | book | No |

| 81 | Limher | limar | to file down, polish, iron out | No |

| 82 | Limhi | lima | lime | No |

| 83 | Limnah | lima | lime | No |

| 84 | Luram | lurio | in love | No |

| 85 | Mahah | mahoma | Mahommed | No |

| 86 | Manti | mantilla | baby clothes; naïve | No |

| 87 | Mathoni | matonismo | thuggery, bullying | No |

| 88 | Melek | melocoton | peach, peach tree | No |

| 89 | Middoni | midi | mini | No |

| 90 | Minon | minon | sweet, cute | No |

| 91 | Mocum | moco | mucus, snot, crest, burnt wick | No |

| 92 | Moriancumer | moribundo | moribund | No |

| 93 | Morianton | morena | moraine | No |

| 94 | Mormon | moro | moorish | No |

| 95 | Moroni | moron | hillock | No |

| 96 | Mosiah | misia | missus | No |

| 97 | Mulek | mule | to bump off | No |

| 98 | Nahom | nahual | spirit | Not an unfitting meaning for a burial ground. |

| 99 | Neas | neceser | toilet bag | No |

| 100 | Nehor | negrero | slave trader | No |

| 101 | Nephi | nefato | stupid, dim | No |

| 102 | Neum | neumatico | pneumatic | No |

| 103 | Ogath | Ogino | rhythm method of birth control | No |

| 104 | Omer | omitir | to leave out, miss out | No |

| 105 | Omner | omni | omni (prefix) | No |

| 106 | Omni | omni | omni (prefix) | No |

| 107 | Onidah | onda | wave | No |

| 108 | Onti | ontology | the real | No |

| 109 | Orihah | originar | to cause | No |

| 110 | Paanchi | panache | mixed salad | No |

| 111 | Pachus | panho | chubby, squat, flat | No |

| 112 | Pacumeni | paciente | patient | No |

| 113 | Pagag | pagar | to pay | No |

| 114 | Pahoran | pajolero | bloody, damned, stupid, naughty | No |

| 115 | Rabbanah | rabanillo | wild radish | No |

| 116 | Rameumptom | ramera | prostitute | No |

| 117 | Riplah | ripiar | to fill with rubble, to shred, to squander | No |

| 118 | Ripliancum | ripiar | to fill with rubble, to shred, to squander | No |

| 119 | Sariah | sarita | straw hat | No |

| 120 | Seantum | sentido | heartfelt, hurt, sensitive, sense | No |

| 121 | Sebus | sebaceo | relating to oil or fat | No |

| 122 | Seezoram | sesamo | sesame | No |

| 123 | Senine | senil | senile | No |

| 124 | Senum | senuelo | decoy, bait, lure | No |

| 125 | Seon | seo | cathedral | No |

| 126 | Shared | serape | blanket | No |

| 127 | Shazer | sacer | sacred | No |

| 128 | Shelem | sello | stamp | No |

| 129 | Shemlon | semillero | seed box, nursery | No |

| 130 | Shemnon | seminario | seminary | No |

| 131 | Sherem | sera | basket | No |

| 132 | Sherrizah | sericultura | silk-raising | No |

| 133 | Sheum | seo | cathedral | No |

| 134 | Shez | sesamo | sesame | No |

| 135 | Shiblon | sibilino | prophetic or mysterious | No |

| 136 | Shim | sima | abyss, chasm, fissure | No |

| 137 | Shimnilom | simil | similar | No |

| 138 | Shiz | sicario | hired killer | No |

| 139 | Shule | sultan | sultan | Potentially an appropriate appelation for a king. |

| 140 | Shum | sumar | to add up | Potentially meaningful as a weight measure. |

| 141 | Shurr | sur | southern | No |

| 142 | Sidom | sidoso | sufferer from AIDS (disease) | No |

| 143 | Siron | Sirio | Syrian | No |

| 144 | Teancum | tea | torch | No |

| 145 | Teomner | teorema | theorum | No |

| 146 | Tubaloth | tubular | roll on | No |

| 147 | Zarahemla | zaramullo | affected, conceited, finicky, amusing | Conceited could potentially work, as Zarahemla is sometimes associated with pride, though it’s a minor connection to a minor meaning of the word. |

| 148 | Zeezrom | zazca | bang, crash | No |

| 149 | Zemnarihah | zanzontle | mockingbird | No |

| 150 | Zenephi | zanzontle | mockingbird | No |

| 151 | Zeniff | zanzontle | mockingbird | No |

| 152 | Zenock | zona | area | No |

| 153 | Zenos | zona | area | No |

| 154 | Zerahemnah | zarzamora | blackberry | No |

| 155 | Zeram | zarzo | hurdle, wattle, attic | No |

| 156 | Zerin | zarzo | hurdle, wattle, attic | No |

| 157 | Ziff | ziper | zipper | No |

| 158 | Zoram | zorra | vixen, whore, bloody | No |

Granted that it appears that wordplay can be coincidental and that the more meanings attributed to a word, the more likely to find a contextual basis in meaning for that word, still, I sense a bit of fudging on Dr. Rasmussen’s part in order to placate the detractors.

I do agree that a name for a person in antiquity might traditionally have been given at birth, but also, might just as easily have been transformed or changed later in life to exhibit said person’s attributes. American Indians appear to have done this with seeming ease, and we’re all familiar with the rather frequent name changes exhibited in the Bible. In other words, I don’t think that too many people should be surprised when an onomastic name actually “fits” the individual’s personality or career, the particular attendant incident relating to the individual, or the resultant “first impressions” of interaction with the individual. Even place names might potentially be adjusted, based upon some overwhelming incident, descriptive feature or popular consensus which might have changed nomenclature over time. (For example, my 300-plus pound, six-foot something friend had a given name, but most people knew him as “Tiny.”)

What I am saying, is that from my perspective, Dr. Rasmussen has been exceedingly generous to the “no correlation” side regarding onomastic wordplay in the Book of Mormon and that his order of magnitude should probably be higher than where he ultimately assigned it. Naturally this is a personal opinion and would obviously be refuted by those opposing.

Still, knowing that some of these onomastic wordplays are so exceedingly “correct,” and “spot-on” as they are, yet there is no method or determination for weighing or “massing” the exceedingly appropriate and accurate ones “heavier” or “weightier” than the merely close ones. This is unfortunate, for the “spot-on” hits are amazing, difficult to measure and seemingly beyond coincidence.

Correct is correct is correct. Yet as Dr. Rasmussen pointed out, incorrect would have been potentially devastating. So correct gets us only four orders of magnitude while incorrect would have blown us out of the water? Somehow that doesn’t seem totally fair to me.

Thanks for your thoughts, Tim.

“I do agree that a name for a person in antiquity might traditionally have been given at birth, but also, might just as easily have been transformed or changed later in life to exhibit said person’s attributes.”

It’s definitely true that ancient names have changed, and that they often did so in a meaningful way that can be traced through the name’s etymology. See the site below for some good examples:

https://godwords.org/name-changes-in-the-bible/

But in the Book of Mormon cases we don’t see evidence of the change itself–we don’t get a part saying that Hagoth’s name was originally one thing and then changed to something else, the way we do for the biblical name changes. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, but the possibility that chance could produce the wordplay should at least encourage humility, and keep us open to the idea that each specific correspondence could just be a cooincidence, even if the set in total suggests that not all of them are.

“This is unfortunate, for the “spot-on” hits are amazing, difficult to measure and seemingly beyond coincidence.”

I too wish that I had a better way of judging the “spot-on-ness” of a given wordplay. At this point, though, that sort of judgment would be almost completely subjective. If you’ve got a good way to quantify it that suggests the Book of Mormon wordplays are better than the chance ones, I’d be all ears.

Cheers!

A couple of observations: Forty years before the Wilcox, et al., study, John A. Tvedtnes did a linguistic analysis of the Nephite and Jaredite onomastica, and found them to be utterly different: “A Phonemic Analysis of Nephite and Jaredite Proper Names.” Newsletter and Proceedings of the Society for Early Historic Archaeology, 141 (December 1977): 1-8.

It is not clear to me why names like Paanchi and Pahoran were excised from your analytic list of 158. Beginning in the late 1940s, the great William F. Albright commented in writing that both were certainly proper Egyptian names, and he told Hugh Nibley that when Nibley was on sabbatical at Johns Hopkins.

Thanks Robert! Tvedtnes’ work was spot on, for sure, though the Wilcox study allowed those differences to be quantified in a way that was helpful for my analysis.

And I’m not sure why you’re saying that Paanchi and Pahoran are missing, since both are represented in the tables in the appendix. They just don’t have a wordplay or a gloss associated with them, so they’re not included in the tables in the body of the essay.

Cheers!

Sorry, Kyler. For some reason I was unaware that your test-list of 158 included only those names which exhibited wordplay or a gloss of some kind. I probably didn’t read carefully enough.